Abstract

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by a compromised epidermal barrier and heightened immunoglobulin E (IgE) levels, often associated with filaggrin (FLG) gene mutations. Genetic factors like FLG mutations and environmental influences, including microbial exposure and pollutants, contribute to the disease’s progression, leading to itchy, inflamed skin. AD frequently coexists with allergic conditions, severely affecting the quality of life. The disease’s pathogenesis involves complex interactions between genetic predispositions, immune responses, and environmental triggers. Despite advances, the development of effective treatments remains challenging due to an incomplete understanding of how FLG mutations influence immune pathways and the variability in AD presentation. Current biomarkers are insufficient to fully capture disease complexity or predict therapeutic responses, highlighting the need for novel biomarkers and personalized approaches. Emerging therapies such as chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy, stem cell therapy, and regenerative medicine show promise in addressing AD’s root causes. This review explores key aspects of AD pathogenesis, focusing on epidermal barrier dysfunction, immune mechanisms, and the need for innovative therapeutic strategies to improve patient outcomes.

Keywords

Filaggrin, dysfunctional epidermal barrier, immune profiling, CAR-T, stem cell therapy, regenerative medicineIntroduction

While pruritic dermatological conditions have been documented for centuries, one of the earliest potential references to atopic dermatitis (AD) is found in the works of the Roman historian Suetonius (69–140 CE), who chronicled a condition affecting emperor Augustus, characterized by hard, dry patches and seasonal ailments [1–4]. Aetius of Amida later coined the term “eczema” in 543 CE, describing it as “boiling out”—a concept influenced by the ancient theory of body humors [5]. It is generally believed that Aetius likely referred to conditions such as carbuncles or furuncles, which are boils or skin abscesses caused by Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) colonizing hair follicles [2, 6]. This historical framework laid the foundation for our current understanding of AD, with significant advancements occurring in the 20th century, such as the introduction of the terms “allergy” and “atopy” by Clemens von Pirquet, Arthur Coca, and Robert Cooke [7, 8]. Later on, Fred Wise and Marion Sulzberger proposed the word “atopic dermatitis” [9], encapsulating the multifaceted nature of the disease.

AD is now recognized as a complex, chronic inflammatory skin disorder, influenced by genetic, immunological, and environmental factors [10–14]. It is marked by a defective cutaneous barrier, leading to enhanced transepidermal water loss (TEWL) and heightened susceptibility to infections and allergens [15]. AD is also characterized by immune hyper-responsiveness, leading to increased keratinocyte (KC) proliferation, acanthosis, and a heightened T helper cell type 2 (Th2)-driven inflammatory response [16–18]. The immunological dysfunction in AD involves abnormal innate, adaptive, and humoral immunity, possibly influenced by epigenetic changes [17–20]. AD is linked to a predisposition for CD4+ Th2 cell differentiation and elevated immunoglobulin E (IgE) levels, resulting in hypersensitivity and related conditions like asthma. The barrier dysfunction in AD is often linked to mutations in the filaggrin (FLG) gene, which disrupts skin integrity and predisposes individuals to allergic sensitization, and elevated serum IgE levels [21, 22]. About 80% of AD patients exhibit these heightened levels of IgE, which correlate with disease severity.

Lipid dysregulation is another critical aspect of AD pathogenesis. Studies have shown a significant depletion in very long-chain ceramides and a rise in short-chain ceramides in AD skin, contributing to impaired barrier function and increased TEWL [15, 23, 24]. Additionally, oxidative stress performs a crucial role in AD, with elevated markers of oxidative damage observed in the skin of individuals afflicted with AD [25, 26]. Mitochondria, the key regulator of oxidative stress, are implicated in AD pathogenesis, potentially offering new therapeutic targets [27–30].

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) report highlights AD as a significant public health concern, with symptoms varying by region, climate, age, and other factors [10]. For instance, cold climates exacerbate AD due to dryness, while hot climates can aggravate lesions through sweating [10, 31]. AD prevalence peaks in early childhood and later life, often coexisting with conditions like asthma, allergic rhinitis, and eosinophilic esophagitis [10].

Infections, particularly with S. aureus, are common in AD, further complicating the management and increasing the risk of severe conditions like impetigo, sepsis, and eczema herpeticum (EH) [10]. The psychosocial impact of AD is profound, with the disease significantly diminishing overall well-being and raising the likelihood of depression and social stigma [10].

Current management strategies for AD include emollients, topical corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and more recently, advanced therapies such as Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors and biologics [10]. Emerging treatments focus on targeting specific pathways involved in AD pathogenesis, including mesenchymal stem cell therapy, chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cells targeting membrane-bound IgE (mIgE), adoptive cell therapy (ACT) with regulatory T cells (Tregs) expanded ex vivo, Treg-targeted immunomodulatory therapies, and mitochondrial-targeted therapies [32–36].

This review aims to explore the multifaceted pathogenesis of AD, examining the role of epidermal barrier dysfunction, immune mechanisms, and emerging biomarkers, and to provide insights into the evolving landscape of AD management.

Epidemiology

AD is a major global skin disease, yet comprehensive epidemiological estimates are lacking. A study conducted by Tian et al. [37] detailed a systematic review of 344 studies to quantify the global and country-specific epidemiology of AD using a Bayesian hierarchical model. The global prevalence of AD was estimated to be 2.6%, affecting approximately 204.05 million individuals, with prevalence rates of 2.0% in adults and 4.0% in children [37]. Females exhibited a higher prevalence (2.8%) compared to males (2.4%) [37]. Significant data gaps exist, with 41.5% of countries lacking epidemiological information on AD, highlighting the need for further research [37]. The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC), conducted from 1997 to 2003, showed a surge in AD prevalence in regions that previously exhibited low prevalence, while areas with high prevalence showed stabilization, indicating the impact of environmental factors [10]. The GBD study, spanning from 1990 to 2017, reported no significant change in the incidence rate of AD per 100,000 individuals. However, the absolute number of AD cases likely increased due to global population growth from 5.3 billion to 7.6 billion [10]. AD is a primary or contributory factor in about 50% of prurigo nodularis (PN) cases, more common in Southeast Asian or African individuals [12, 13]. A Japanese study found 30.9% of moderate AD patients and 56.3% of severe AD patients had PN [38]. PN often persists even after AD symptoms improve [12].

Understanding the epidermal characteristics critical for barrier integrity

The multilayered epidermis of the skin is a finely structured assembly of stratified layers, each harmonizing in purpose to form a cohesive shield. The topmost layer, stratum corneum (SC), serves as the initial line of defense. It consists of KCs that continuously undergo cell division, proliferation, and apoptosis, maintaining the skin barrier’s integrity and safeguarding the underlying layers. This barrier effectively shields against harmful substances, as KCs engage with T cells to enhance immune responses and release proinflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-8 and interleukin-1β (IL-8 and IL-1β) [39]. The extracellular lipids within this layer include ceramides, free fatty acids (FFAs), cholesterol, and ultra-long acyl ceramide subclasses. These lipids are vital for sustaining barrier permeability and function, while their antimicrobial properties contribute to pathogen exclusion [15]. Key proteins such as FLG, loricrin (LOR), involucrin (IVL), and antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) perform crucial roles in establishing a resilient skin barrier [40, 41]. AMPs including S100 calcium-binding protein A7 (S100A7) protein enhance the activity of tight junction (TJ)-associated proteins and facilitate the repair of compromised epidermal barriers [41–45].

The subsequent layers include the stratum lucidum (SL), stratum granulosum (SG), stratum spinosum (SS), and stratum basale (SB), with each stratum contributing uniquely to the overall protective function including skin barrier integrity. The second layer, SL, comprises a slender, densely packed layer of anucleate, fully keratinized cells. Following it is the SG layer, where FLG-containing keratohyalin granules are produced due to the liquid-liquid phase separation of the FLG protein [46, 47]. Langerhans cells (LCs) interact with KCs in this SG layer, extending dendrites through TJs to capture antigens [48, 49]. Next, the SS layer overlays the SB and comprises various cells with diverse properties. Finally, the innermost layer, SB, comprises rapidly proliferating KCs connected to the dermis by multiprotein linkages. Its TJs support cornification and barrier function [47, 48, 50].

FLG metabolism: highlighting its importance in AD

In the SG, FLG is synthesized as a polymer known as profilaggrin (Pro-FLG), comprising 10–12 FLG monomer repeats, which are contained in keratohyalin granules [51]. Pro-FLG is split into FLG monomers by proteases such as channel-activating protease 1 (CAP1)/serine protease 8 (Prss8) and skin aspartic acid protease (SASPase)/aspartic peptidase retroviral-like 1 (ASPRV1) during its shift from the layer SG to SC [52, 53]. These monomeric units attach to keratin (KRT) filaments, forming a KRT-bound FLG bundle within corneocytes. As FLG-KRT ascends to the upper SC, it dissociates from KRT filaments to undergo additional metabolism, where FLG and KRT1 are citrullinated by peptidyl arginine deiminase [54]. The liberated monomers of FLG are further metabolized into various amino acids that form skin protective factors such as urocanic acid (UCA) and pyrrolidine carboxylic acid (PCA). Various proteases, such as caspase14, calpain1, and bleomycin hydrolase, catalyze this metabolism [55]. UCA is a critical ultraviolet-absorbing chromophore in the SC, helping maintain the acidic pH of the skin [55, 56]. PCA is an essential component of natural moisturizing factors (NMFs) [57], crucial for maintaining hydration in the SC. Thus, FLG and its breakdown products perform diverse functions in upholding the barrier function of the SC. Investigations into genetic modification techniques have revealed that mice devoid of FLG have an impaired SC barrier and elevated sensitization to environmental stressors and immune responses [58, 59].

Etiopathogenesis of AD

Etiology

AD can be classified by the age of onset into three principal categories: early, adult, and elderly-onset AD [60, 61]. Early-onset AD encompasses the infantile, childhood, and adolescent stages [61]. Infantile AD generally appears in children under the age of 2; childhood AD occurs between the ages of 2 and 12, and adolescent AD affects those between 12 and 18 years [61]. Adult-onset AD begins in individuals over 18 years old [61]. Finally, elderly-onset AD is characterized by its arrival at or after 60 years of age [61]. Offspring of affected parents have over a 50% chance of developing atopic symptoms, rising to 80% if both parents are afflicted [62]. FLG mutations, causing epidermal barrier dysfunction, can lead to ichthyosis vulgaris, allergic rhinitis, and keratosis pilaris, found in about 30% of AD patients [62]. Food hypersensitivity, affecting 10–30% of individuals, can exacerbate AD, though not all cases are due to FLG mutations [62].

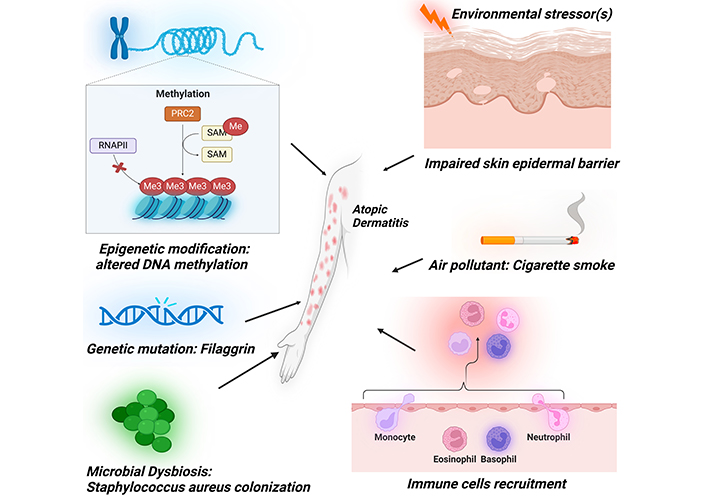

The etiopathogenesis of AD is complex and involves diverse factors such as environmental stressors, epigenetic modifications, genetic mutations, and immune system dysregulation (Figure 1).

Diverse array of etiopathogenic factors contributing to the development of atopic dermatitis. These encompass epidermal barrier dysfunction, immune system dysregulation, cigarette smoke exposure, epigenetic modifications, genetic mutations, and microbial influences. PRC2: polycomb repressive complex 2; RNAPII: RNA polymerase II; SAM: S-adenosylmethionine; Me: methyl group (–CH3). Created in BioRender. Baidya, A. (2024) BioRender.com/j36t564

There are two forms of AD, intrinsic AD, and extrinsic AD. Intrinsic AD also referred to as non-allergic AD, accounts for 12%–27% of cases and typically begins in adulthood, predominantly affecting women with milder symptoms that are not allergen-induced [60, 61] and having Th1-dominant immune response [63, 64]. Intrinsic AD also exhibits normal epidermal barrier function, reduced eosinophil infiltration, lower thymus and activation-regulated chemokine (TARC) C-C motif chemokine ligand 17 (CCL17)/TARC expression, no association with FLG gene mutations, and lower susceptibility to skin infections [64]. In contrast, extrinsic AD, or allergic AD, makes up 73%–88% of cases, usually manifesting in childhood and affecting both genders with greater severity [64]. This form of AD is driven by allergens, elevated IgE levels, and Th2 cytokines, indicating a Th2-skewed immune response [63, 64]. Extrinsic AD also leads to a compromised epidermal barrier, increased eosinophil infiltration, higher CCL17/TARC expression, increased association with FLG gene mutations, and a heightened risk of infections [64–66]. Despite these differences, studies have also revealed that both intrinsic and extrinsic AD patients exhibit similarly elevated blood levels of soluble receptors, soluble clusters of differentiation 23, 25, 30 (sCD23, sCD25, and sCD30) [64, 67]. Furthermore, both forms of AD show decreased levels of human β-defensin 3 (hBD-3) expressions [64, 68] and increased levels of neurotrophins indicating a shared neuroimmune basis between the two forms of AD [64, 67, 69].

Environmental factors

Environmental factors, including microbial toxins, climate, and smoking rates, can directly influence the resilience of the cutaneous epidermal barrier and its sensory and immune systems, each contributing to the pathogenesis of AD [70].

Microbial exposure

House dust mites (HDMs), prevalent allergens, can elicit allergic responses in sensitized individuals. Their droppings contain potent allergens that exacerbate AD symptoms. Sensitization to HDMs has been linked to the onset of AD [71]. In AD patients, an impaired epidermal barrier increases skin permeability, allowing airborne proteins and microbes to penetrate the epidermis [71]. HDM allergens interact with local immune cells, initiating Th2 immune responses. Additionally, HDM-specific IgE antibodies can be detected in AD patients, further aggravating eczema [71].

Bacterial infections such as S. aureus colonization affect over 90% of AD patients due to decreased AMPs like hBDs and cathelicidins in the epidermis during the acute phase of AD, which leads to increased sensitivity to infection. When S. aureus invades the skin, pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) of KCs recognize the microbe-associated molecular pattern (MAMP) of S. aureus and trigger innate immune responses [72]. The two primary constituents of the cutaneous epidermal barrier, AMPs and TJ protein claudin 1 (CLDN1), are rapidly upregulated in normal KCs upon Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) activation. It has recently been reported that impaired TLR2 function is linked to the pathophysiology of AD, thereby compromising the skin barrier [73].

Certain S. aureus products, such as α-toxin [74, 75], enterotoxins [75], superantigens [76, 77], phenol-soluble modulins (PSM) [78, 79], protein A [75], Panton-Valentine leucocidin [80], exfoliative toxins [81, 82] and V8 serine protease [83], can damage the skin’s protective layer. Superantigens of S. aureus, such as staphylococcal enterotoxins A, B, and C, directly stimulate B cells, promote basophil degranulation, and certain IgE-dependent mast cells to release histamine, thereby worsening the condition further [76].

Upon bacterial infection, activated macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs) rapidly produce IL-23 at the infection site, which activates local Th17/ThIL-17 cells [84, 85]. These cells secrete IL-17, a potent chemoattractant for neutrophils, which are then recruited to the site of inflammation, thereby aggravating the situation [84].

S. aureus infections also trigger the release of the “alarmin” cytokines from the skin epithelium. These trigger type 2 innate immune responses by activating eosinophils, Th2 cells, basophils, macrophages, type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s), and mast cells, thereby promoting IgE-mediated inflammation [60].

Viral infections significantly exacerbate AD, with herpes simplex virus (HSV) notably leading to EH in 7%–10% of patients, resulting in severe complications [86]. In addition to HSV, viruses like molluscum contagiosum and human papillomavirus can also worsen AD symptoms. AD patients are more susceptible to upper respiratory infections, though no increased prevalence of COVID-19 has been reported among them, even with dupilumab treatment [86]. This monoclonal antibody reduces the risk of EH, highlighting the importance of managing viral infections to mitigate their impact on AD severity and improve patient outcomes [86].

Psychological stress is a significant environmental factor influencing the course of AD, a chronic inflammatory skin condition marked by pruritus and recurrent eczematous lesions [87]. Stress not only exacerbates skin inflammation through neurogenic pathways but also leads to a vicious cycle of worsening symptoms. The visibility of AD can impact sleep quality and self-esteem, contributing to social withdrawal and a decreased quality of life [87]. Studies show that individuals with AD have heightened odds of depression, anxiety, and suicidality. Furthermore, chronic inflammation in AD can breach the blood-brain barrier, potentially leading to cognitive impairment. Thus, healthcare providers must prioritize mental health in AD management [87].

Climate

Both extreme heat and cold climates trigger skin inflammation via transient receptor potential channels responsible for thermal and mechanical sensing. While low temperatures activate transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) to produce proinflammatory cytokines and downregulate FLG expression, leading to a dysfunctional epidermal barrier, high temperatures result in the generation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and exacerbate AD via TRPV1, 3, and 4 [70, 88]. Cold climates and low humidity intensify AD symptoms by inducing dryness [10, 31], whereas excessive heat exacerbates lesions through increased sweating [10]. A drop in the external temperature and humidity impacts water loss, worsens skin barrier functions, and increases sensitivity to irritants and allergens [31]. The impact of precipitation on AD is multifaceted, influenced by regional baseline rainfall and seasonal variations [70]. Higher precipitation levels could indirectly alleviate AD by lowering aeroallergen and air pollutant levels [70]. High UV exposure causes DNA damage, apoptosis, and inflammation, which impairs the skin barrier [70, 89]. Ozone combined with UV radiation shows additive inflammatory effects [90, 91].

Air pollutants and smoking

Air contaminants such as particulate matter (PM), volatile organic compounds (VOC), cigarette smoke, and other sources contribute to AD by disrupting the skin barrier, increasing oxidative stress, and dysbacteriosis [91–93]. VOC and cigarette smoke exposure increase TEWL [94], while PM disrupts skin barrier integrity by affecting structural proteins [95, 96] and promoting inflammation via nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB) [97]. Air pollution can also exacerbate AD by causing cutaneous dysbiosis, increasing S. aureus colonization, and reducing beneficial resident microflora. Allergens, such as pollen, cause skin inflammation in sensitized individuals through Th2 signaling [18]. PM triggers mitochondrial dysfunction by inflicting considerable structural damage [98, 99]. This dysfunction is typically signaled by a reduction in ATP levels, as seen in KCs and fibroblasts exposed to PM2.5 [98]. The resulting dysfunction in mitochondria causes a rise in the formation of oxidative radical formation, and elevated mitochondrial Ca2+ levels in vitro [98, 99]. Cigarette smoke exposure is known to exacerbate AD by contributing to skin inflammation and barrier dysfunction [100]. Additionally, smoking can influence immune responses, increasing susceptibility to allergens and irritants, further worsening AD symptoms [100]. Thus, acknowledging the detrimental impact of cigarette smoke on AD is essential for comprehensive management.

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER), which stores the majority of intracellular Ca2+, becomes stressed when the cellular Ca2+ equilibrium is disrupted [101]. PM exposure has been found to elicit ER stress, as evidenced by an increase in intracellular Ca2+ levels that further leads to mitochondrial and ER stress, as indicated by swelling in both organelles.

Epigenetic factors

Various studies have indicated that epigenetic mechanisms, including differential promoter methylation, acetylation, or regulation by non-coding RNAs, play important roles in AD pathogenesis, whose reversal has been examined to reduce inflammatory burden via alteration of secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines [102]. Significant evidence revealed that altered genetic and epigenetic expressions in immune cells can potentially contribute to AD pathogenesis [103, 104]. A genome-wide methylation profiling study comparing DNA methylation patterns between AD patients and healthy individuals uncovered a notably different methylation profile in the patients [105]. For instance, AD patients exhibit elevated FcεRI (high-affinity receptor for the Fc region of immunoglobulin E) and IgE gene expression levels in their peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) due to decreased DNA methylation, thereby altering their sensitivity to allergens.

Several pioneering studies have investigated DNA methylation alterations in AD and their potential effects on gene regulatory mechanisms [106]. Early investigations into the patterns of methylation status in AD revealed significant differences between cases and normal controls [106, 107]. Using chip-based studies, they analyzed gene expression and DNA methylation status at CpG (5’-C-phosphate-G-3’) sites in AD lesional and non-lesional epidermis [107]. Notably, CpG methylation remained largely unaltered in T and B lymphocytes and whole blood, with significant alterations recognized in AD lesional epidermis compared to normal controls. Specifically, upregulated expressions of S100A2, S100A7, S100A8, S100A9, and S100A15 were noted, with hypermethylation detected only for S100A5 [107]. Increased expressions of KRT6A and KRT6B in KCs were noted, accompanied by decreased methylation specifically in KRT6A [107]. Additionally, elevated expressions of 2’,5’-oligoadenylate synthetase 1 (OAS1, OAS2, and OAS3) in innate immune cells were found, with decreased methylation specifically in OAS2. These findings underscored distinct changes in DNA methylation in KCs and innate immune cells that contribute to AD pathology.

Histone modifications, particularly acetylation, play a crucial role in allergic conditions, yet their impact on AD remains underexplored [108]. Studies show increased transcriptionally active histone marks, histone 3 acetyl (H3ac) and histone 4 acetyl (H4ac), in allergic asthma, correlating with IL-13 levels in CD4+ T cells [108]. A recent investigation into microbiome-driven epigenetic changes highlighted butyric acid (BA), produced by Staphylococcus epidermidis, as a histone deacetylase inhibitor that enhances histone acetylation, promoting gene expression [108]. This mechanism was linked to reduced S. aureus growth in AD models, suggesting potential therapeutic avenues targeting histone modifications to mitigate AD’s inflammatory responses [108]. More research is warranted to clarify these interactions.

Immunological factors

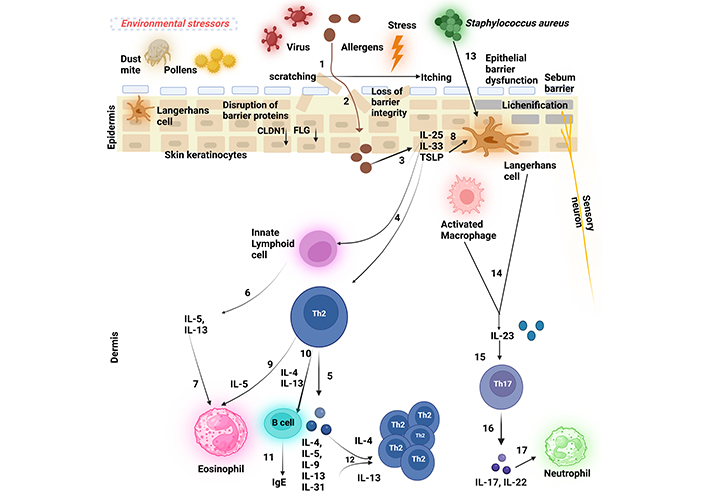

Skin-resident cells, including KCs and many immune cells, are crucial in driving inflammatory responses in AD [109]. Moreover, immune cells such as T lymphocytes, plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs), monocytes, and granulocytes that migrate from the bloodstream, further contribute to the development of eczema [110]. Although these immune cells interact in a highly complex manner, the immunopathogenesis of AD is primarily driven by a Th2-dominant immune response (Figure 2).

The schematic figure depicts the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis (AD). (1) A persistent ‘itch-scratch cycle’ occurs due to the disruption of the essential epidermal proteins such as filaggrin (FLG) and claudin 1 (CLDN1) that results in a compromised epidermal barrier, facilitating allergen penetration (2) into the skin and inflicting damage on keratinocytes (KCs), (3) These damaged KCs release ‘alarmins’, interleukin-25 (IL-25), interleukin-33 (IL-33), and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), which (4) activate Th2 cells and innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) at the site of the inflamed lesion, (5) leading to the production of Th2 cytokines (6) ILCs, primarily ILC2s, secrete interleukin-5 (IL-5) and interleukin-13 (IL-13), (7) with IL-5 subsequently attracting eosinophils. Additionally, (8) TSLP triggers the development of Langerhans cells (LCs) (9) which, in turn, promotes Th2 cell activation. (10 and 11) Th2 cells secrete Th2 cytokines such as interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-13 that drive B cells to generate immunoglobulin E (IgE), contributing to hypersensitivity type 1 reaction. (12) Th2 cytokines further stimulate Th2 cells in an autocrine manner. (13 and 14) Upon bacterial infection, most commonly by Staphylococcus aureus, LCs rapidly produce interleukin-23 (IL-23) at the site of infection, (15) thereby activating local Th17/ThIL-17 cells. (16) These cells secrete the Th17 cytokines (17) that are potent chemoattractants for neutrophils. Created in BioRender. Baidya, A. (2024). BioRender.com/d04p354

Introduction of external factors

When external factors such as allergens penetrate the compromised epidermal barrier (due to disruptions in essential proteins like FLG), they interact with epithelial cells. This initial contact leads to KC damage and the release of ‘alarmins’, which are critical for activating the immune response.

Activation of immune cells

Following the release of alarmins, ILC2s and Th2 cells are activated at the site of inflammation, leading to a cascade of cytokine production. This includes the recruitment of eosinophils and the differentiation of T helper cells.

Roles of T cell subsets

T cells are central to acquired immunity and play crucial roles in the pathogenesis of AD. The pathomechanisms of many immune-mediated diseases can largely be attributed to the balance among different T helper cell types, specifically Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells [111].

The immunological response in AD is marked by a two-stage inflammatory phase [112]. During the “acute phase”, a Th2-skewed response is predominant, characterized by the production of Th2 cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-13, which drive IgE-mediated hypersensitivity and eosinophilic inflammation. Elevated levels of Th2 cytokines are consistently observed in both severe and persistent AD lesions compared to normal skin. In the “chronic phase”, this Th2-dominated response transitions to a Th1-skewed response, where there is a decrease in the levels of IL-4 and IL-13, accompanied by an increase in IL-5 and IL-12 levels [113].

Th2 cells: Central to the pathogenesis of AD, Th2 cells predominantly produce cytokines that drive IgE-mediated hypersensitivity and eosinophilic inflammation, contributing significantly to the acute phase of the disease.

Th1 cells: While primarily involved in the immune response against intracellular pathogens, Th1 cells become more prominent in the chronic phase of AD. Their presence may exacerbate symptoms by contributing to ongoing inflammation.

Th17 cells: Several studies reveal marked Th17 cell infiltration in acute or severe AD skin lesions compared to chronic or persistent lesions [114]. These cells are involved in the response to extracellular pathogens and contribute to skin inflammation through the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-17, which enhance the synthesis of IL-6 and IL-8 by KCs [115]. This cytokine environment aids in recruiting neutrophils and modulating fibroblast function [116].

Additionally, Tregs also play a role in modulating skin immune responses. Research has revealed a notable rise in the number of Tregs in the bloodstream [117, 118] and lesions on the skin [119] of AD individuals. However, a study found that Tregs in AD patients lose their immunosuppressive function when activated by superantigens from S. aureus [120]. This loss of function could lead to worsened inflammatory reactions in AD individuals, particularly those with S. aureus infections.

ILCs

ILCs, now recognized as vital players in skin immunity, are categorized into three groups depending upon their developmental pathways and cytokine release profiles: group 1 ILCs that produce interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α); group 2 ILCs (ILC2s); and group 3 ILCs (ILC3s) that produce key Th17 cytokines [121].

AD patients show an abundant population of ILC2s [122, 123], and these cells are sufficient to develop AD-like symptoms in mice as well [124]. Their activity is modulated by cytokines derived from KCs [125].

DCs

DCs play a crucial role in initiating and driving the early stages of AD. Due to compromised barrier integrity, exogenous antigens can easily enter the epidermis and dermis and get captured by skin-resident DCs. In AD lesions, two distinct kinds of epidermal DCs are found: LCs and inflammatory dendritic epidermal cells (IDECs) that infiltrate the skin [126]. Both LCs and IDECs express significant levels of FcεRI, the receptor with a high affinity for IgE, on their surfaces. This expression enables LCs and IDECs to effectively respond to various antigens in an antigen-specific manner by utilizing IgE molecules bound to FcεRI, facilitating efficient capture and processing of allergens.

Upon encountering antigens, DCs present the antigens to the naïve T cells. A finding revealed that epidermal DCs (also called LCs) highly express the receptors for thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), a key factor in promoting Th2 polarization and the development of AD [127, 128].

pDC, a type of DC, is capable of producing significant quantities of type 1 interferons. Intriguingly, skin specimens from individuals diagnosed with psoriasis vulgaris and contact dermatitis exhibited elevated levels of both IDECs and pDCs. Conversely, only a minimal presence of pDCs was observed in AD lesions [129]. This specific deficiency of pDCs in AD patients might render them more vulnerable to cutaneous viral infections.

Eosinophils

The Th2 cell-derived cytokine IL-5 acts as a chemoattractant for eosinophils. During AD flare-ups, elevated levels of eosinophil chemoattractants like IL-5, eotaxin [130], and eosinophil cationic proteins have been reported, suggesting degranulation of eosinophils at the lesion site [131]. A study demonstrated that a significant number of infiltrating eosinophils have been observed in KCs overexpressing IL-33, which is enough to induce skin pathology similar to AD [132]. This finding indicates that ILC2s might be crucial in drawing eosinophils to the lesional site of the AD skin, with their activity being influenced by IL-33 produced by KCs [125].

Mast cells

In acute AD lesions, mast cell numbers are normal but show signs of degranulation [133]. Conversely, in chronic AD lesions, there is a notable rise in mast cells [133, 134] and subsequent degranulation leads to an increase in histamine levels in the plasma of AD individuals [135]. Mast cells are the primary source of Th2 cytokines with studies showing that 66% of mast cells in AD skin express IL-4 and 20% express IL-13 [136–138]. Furthermore, mast cells are closely associated with endothelial cells in AD-affected individuals, suggesting that they may trigger the proliferation of vascular endothelium through factors driving proangiogenesis [139], thus indirectly promoting inflammation by increasing vasculature at inflammatory sites.

Several studies have reported a notable association between mast cell-associated gene polymorphisms and AD. One study found a potential link between a polymorphism in the β chain of the FcεRI on IgE and AD [140]. This polymorphism can lead to increased surface expression of the receptor and amplified intracellular signaling cascade, resulting in mast cell activation dependent on IgE. Additionally, chymase, a chymotrypsin-like serine protease contained within mast cell granules, causes hydrolysis of several substances like pro-collagen, lipoproteins, metalloproteases, and angiotensin I, which is increased in AD skin [141]. A study reported a strong association between mast cell chymase genetic variants and AD [142].

Dysfunctional epidermal barrier

In AD patients, at least three factors contribute to barrier dysfunction: (1) abnormalities in FLG gene expression, (2) decreased skin ceramide levels, and (3) excessive activation of epidermal proteases [30].

Deficiency of FLG

The FLG gene is found within the epidermal differentiation complex (EDC) [143]. There are 27 genes in the EDC, 14 of which are expressed as proteins in the cornified envelope during the last stage of KC differentiation [144]. The remaining thirteen genes in the EDC encode proteins potentially serving as signal transducers when KCs and other cells differentiate [144].

In 2006, direct evidence confirmed a significant association between the occurrence of AD and FLG gene mutations among individuals with the condition [145–148]. FLG is crucial for preserving the function and integrity of the epidermal barrier, as it helps in forming bundles made up of KRT filaments and contributes to the hydration of the SC through its breakdown products, such as NMFs [149]. Lack of FLG gene has demonstrated heightened penetration of antigens through the skin, resulting in amplified immune responses [145, 150]. Notably, individuals with intrinsic AD typically do not display barrier disruption or carry mutations in the FLG gene [64, 145]. This suggests that epidermal barrier disruption is a defining feature of the extrinsic form of AD.

Lipid alterations

The main lipids of the outermost skin layer, the SC, comprise ceramides, FFAs, etc. [151, 152]. An optimal ratio of different lipids in this layer is essential for preserving the integrity and function of the epidermal barrier [153]. KCs release these lipids into the extracellular spaces and are carried to the SC by lamellar bodies, mainly comprising phospholipids, sphingolipids, and cholesterol [153]. Inside the lamellar bodies, the lipids are processed by different enzymes, including sphingomyelinase, glucocerebrosidase, and phospholipase [153]. Mutations in these lipid-processing enzymes or changes in the protease activity could impair the epidermal barrier [154].

Ceramide is one of the important lipids affected in AD [155, 156]. Ceramide is a sphingolipid consisting of a long-chain fatty acid linked to sphingosine via an amide bond and it is synthesized in the epidermis, especially in the SG [157]. Research has shown a marked depletion in ceramide levels in the affected skin of AD individuals compared to those with healthy skin [145, 157–159]. β-Glucocerebrosidase (GBA) is the main enzyme responsible for ceramide production in the SC, and its dysfunction can be observed in AD [157]. Reduced levels of prosaposin, a precursor protein essential for GBA activation, have been observed in AD patients [157, 160]. Conversely, GBA activity in the SC did not differ in AD individuals. [157, 161]. However, recent research using an activity-based probe revealed that GBA activity was higher in the epidermis of healthy controls compared to the lesional skin of AD individuals. This altered distribution of GBA activity was associated with a reduction in ceramide levels in the SC [157, 162].

Abnormal skin lipids in AD are influenced by a heightened type 2 immune response, with inflammatory Th2 cytokines [15, 40, 41, 157, 163–170] resulting in decreased total ceramide and long-chain fatty acid levels with altered chain lengths. Consequently, these lipid changes lead to elevated trans-epidermal water loss in AD patients [145, 171]. Consistent with this fact, a study revealed that ceramide-deficient mice exhibit impaired water-holding capacity and barrier function [145, 172].

IL-4 has been demonstrated to inhibit the expression of GBA and acid sphingomyelinase (aSMase), as well as the synthesis of ceramides in human epidermal skin [166]. Additionally, IL-4 has been shown to retard barrier healing following severe barrier breakdown in murine models [173]. Depletion in the expression of elongation of very long chain fatty acids 1 (Elovl1) and Elovl4, along with lower levels of ceramides, has been observed in AD-affected skin [174]. TNF-α and Th2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-13, IL-31) have been found to decrease long-chain FFAs and acyl ceramides in AD-affected skin, reducing the expression of ELOVL1 and ceramide synthase 3 (CerS3), both essential for skin barrier integrity [175]. Additionally, a significantly altered expression of GBA, aSMase, ELOVL1, and CerS3 has been reported in AD patients [176].

Altered balance between epidermal proteases and protease inhibitors

The integrity of the skin’s epidermis depends significantly on the equilibrium between the skin proteases and their inhibitors. Corneocytes, the differentiated flattened KCs, form the barrier’s foundation and are rich in NMFs, crucial for maintaining skin hydration [177]. These KCs are surrounded by a lipid lamellae layer that prevents water loss and enhances barrier impermeability [177]. Corneodesmosomes, which bind corneocytes together, depend on a delicate balance between proteases, like human kallikrein (KLK) peptidases KLK5, KLK7, and KLK14, and protease inhibitors, such as lympho-epithelial Kazal-type-related inhibitor (LEKTI) [encoded by Kazal-type 5 serine protease (SPINK5)] and cystatin A [145, 177]. This balance regulates desquamation and barrier integrity. Under normal conditions, proteolysis is restricted to the upper SC, maintaining a strong barrier that blocks allergen entry [177]. However, an increased pH in the SC enhances protease activity, weakens corneodesmosomes, and impairs the barrier. This is caused by FLG mutations that reduce NMF levels, leading to a rise in the SC’s pH. As a result, protease activity increases while protease inhibitors become less effective, ultimately disrupting lipid synthesis and compromising the barrier’s integrity. SPINK5 mutations significantly contribute to the pathogenesis of AD through impaired expression of the serine proteinase inhibitor LEKTI. These mutations result in defective protein production, leading to dysregulation of proteinases involved in skin barrier function. Specifically, SPINK5 is crucial for KC differentiation and the regulation of desquamation, as its loss may exacerbate skin permeability barrier dysfunction typical in AD patients. Moreover, a deficiency in LEKTI could enhance susceptibility to serine proteinase-mediated inflammation, further complicating the clinical presentation of AD. In Netherton’s disease, characterized by severe skin conditions, SPINK5 mutations result in significant barrier dysfunction, often necessitating advanced treatment approaches [145, 178].

Diagnostic evaluation of AD

The primary diagnostic approach for eczema involves a comprehensive review of the patient’s medical history. When, where, and how frequently the rash develops are the important questions that an allergist or dermatologist commonly asks [179]. The findings of a traditional physical examination vary by age group. Infants develop oedematous papules and plaques, which may include vesicles or crust, on the head, face, and extensor extremities. Adults, on the other hand, usually have chronic lichenified lesions, which are more common on the hands [12, 19].

Blood testing is commonly carried out to look for high levels of eosinophils and IgE antibodies [180]. Allergen-specific IgE or other pro-inflammatory cytokines testing by employing enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is even more helpful as it assesses antibody levels specific to individual allergens [180]. Collecting buccal swabs with a cotton applicator to get cells as a source of DNA material can be useful in looking for mutations in the FLG gene [181]. Allergy skin testing such as skin prick tests can be used to determine whether eczema-related sensitization to a particular allergen is present or absent in response to common foods or inhaled allergens [180]. Skin biopsies are frequently employed in the evaluation of skin pathology in AD [182].

Clinical variants of dermatitis and their differential diagnostic criteria

AD is a prevalent and multifaceted cutaneous condition with various medical presentations [12]. However, several other forms of dermatitis can present with symptoms similar to AD, complicating the disease diagnosis. Distinguishing between these conditions is crucial for appropriate management and treatment [12]. The following table outlines various clinical presentations or variants of dermatitis that may overlap with or resemble AD [12]. Each entry in the table provides a concise overview of the dermatitis variant, along with the specific differential diagnostic criteria or associated factors that distinguish it from AD. This comparative summary is designed to aid healthcare professionals in accurately diagnosing and differentiating these conditions to ensure effective patient care (Table 1).

Clinical variants of dermatitis that resemble atopic dermatitis (AD) and their differential diagnostic criteria [12]

| Name of variant of dermatitis | Description | Differential diagnostic criteria/Associated factors to distinguish it from AD |

|---|---|---|

| i. Prurigo nodularis (PN) | PN is characterized by intensely itchy, firm nodules that appear on the extremities, particularly the arms and legs. These nodules are often excoriated and can lead to significant skin thickening and scarring. | Associated with infections, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, psychiatric disorders, and neuropathic disorders. |

| ii. Nummular (Discoid) dermatitis | Nummular dermatitis is marked by coin-shaped, itchy, and scaly patches on the skin. The lesions are typically well-defined and may appear on the arms, legs, and torso. | Distinguished by well-defined round lesions; more commonly linked to dry skin or contact dermatitis.

|

| iii. Lichenoid dermatitis | This type presents with lichenoid (scaly, purple) plaques that resemble lichen planus. The lesions are typically flat-topped and can be itchy. | Differentiated by its lichen-like appearance or lichenification of the skin and mucous membranes and association with drugs or systemic diseases. |

| iv. Follicular dermatitis | Characterized by inflammation around hair follicles, leading to papules or pustules. It often affects areas with dense hair follicles, like the scalp or back. | Distinguished by follicular involvement and less likely to have the widespread pruritus typical of AD.

|

| v. Dyshidrosis or pompholyx | Dyshidrosis is marked by small, itchy, fluid-filled blisters on the skin. The blisters can be painful and may lead to peeling and scaling. | Characterized by vesicular eruptions on palms and soles, often associated with sweating or stress.

|

| vi. Erythrodermic | This severe form of dermatitis involves widespread inflammation and exfoliation of the skin, covering large areas of the body. It can cause redness, scaling, and severe itching. | Characterized by extensive involvement of the skin, differing from AD by its severe presentation and systemic involvement. |

Therapeutic strategies and targets of AD

The management of AD often poses challenges due to its complex etiology and the varying responses of individuals to treatment [183]. Without effective treatment, AD can result in severe complications, including secondary infections, sleep disturbances, and psychosocial issues [183]. This complexity necessitates a multifaceted therapeutic approach targeting different aspects of the disease. The following section outlines current therapeutic strategies and emerging targets aimed at improving outcomes for AD patients. This comprehensive overview includes methods to enhance epidermal barrier functions, modulate the skin microbiome, and target both innate and adaptive immune responses. Understanding these therapeutic options is crucial for developing effective management strategies tailored to individual patient needs.

Enhancing epidermal barrier functions

To strengthen the skin barrier, specific ingredients in moisturizers play a crucial role [184]:

Physiological humectants (urea, glycerol) stop excessive water loss and maintain the SC’s moisture content [184].

Dexpanthenol promotes epidermal differentiation and lipid synthesis.

Emollients (such as glycerine cream and sorbolene) soften the skin [184].

Histamine release can be blocked by anti-itching medications (such as glycerol), which enables the SC to start healing [184].

Petrolatum is known to possess antimicrobial activity and hence maintain epidermal barrier function.

Modulating the skin microbiome

Recent research highlighted significant findings in AD pathogenesis involving Roseomonas mucosa (R. mucosa), a gram-negative bacterium [185]. It was observed that R. mucosa carriage was reduced in AD patients compared to healthy controls [185]. In mouse and cell culture models, R. mucosa from healthy subjects showed improved outcomes, while AD-derived subjects revealed neutral or worsening effects [185]. Initial clinical trials (NCT03018275) showed promising results with topical live R. mucosa, reducing pruritus without adverse effects [186]. Another product, FB-401, containing R. mucosa strains, activated anti-inflammatory pathways [185, 186].

Staphylococcus hominis A9 (ShA9), isolated from healthy human skin, has been shown to inhibit the appearance of S. aureus [187]. Clinical trials (NCT03151148) demonstrated the efficacy of topical ShA9 in AD patients with S. aureus, suggesting potential bacteriotherapy. Niclosamide ATx201 [188], a 2% cream, showed promise in reducing S. aureus colonization and improving inflammatory response and skin barrier function in phase-II trials.

Nitrosomonas eutropha strain B244, an ammonia-oxidizing bacterium, reduced pruritus and S. aureus counts in adult AD patients in a phase IIa trial through nitric oxide production. Omiganan pentachloride (CLS-001), a cationic host defense peptide, and other microbiome modulators like EDP1815, STMC-103H, and KBL697 are also being investigated for their potential in managing AD through various clinical trials [189–191].

Targeting the innate immune responses

TSLP, IL-25, and IL-33 are the main alarmins that indicate potential treatment targets for AD [192]. Tezepelumab, an anti-TSLP antibody, phase 2a study (NCT02525094), has demonstrated promising outcomes in AD [193, 194].

Anti-IL-1α antibody bermekimab (MABp1), which was made for hidradenitis suppurativa [195], demonstrated a strong reduction in pruritic conditions. In addition to hidradenitis suppurativa, the clinical trial is under process with MABp1 in individuals with moderate to intense AD [196].

IL-36, which is upregulated in AD, represents another target of AD. A clinically tested anti-IL-36R-antibody spesolimab was examined for AD [197].

Targeting the adaptive immune responses

Targeting the key Th2 cytokines

Drug development strategies for modulating Th2 responses primarily target key cytokines IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, and their receptors. Dupilumab binds to IL-4Rα, affecting both IL-4 and IL-13 signaling [189, 198, 199]. ASLAN004 blocks IL-4 and IL-13 by targeting IL-13Rα1 on the type II receptor [189]. Tralokinumab specifically inhibits IL-13 by preventing its interaction with IL-13Rα1 and IL-13Rα2 [200]. Lebrikizumab, while not blocking receptor binding, disrupts the IL-4Rα and IL-13Rα1 heterodimer formation, hindering downstream signaling [201].

Targeting IgE

AD patients generally have elevated IgE serum levels, a sign of Th2 immune response. It has been reported that anti-CεmX (FB825), an antibody targeting mIgE, depletes IgE-committed B cells and lymphoblasts through apoptosis, which is still in the phase IIa study [189, 202].

Targeting phosphodiesterase 4

Phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) has been demonstrated as a potential therapeutic target for treating allergic conditions, including AD [203]. Lotamilast (RVT-501/E6005) has shown encouraging results in trials involving Japanese adults and children in a cream formulation [189]. According to a phase IIa study, adults and adolescents treated with difamilast as a cream showed promising results [189]. Another successful drug discovered, 2-{6-[2-(3,5-dichloro-4-pyridyl)acetyl]-2,3-dimethoxyphenoxy}-N-propylacetamide (LEO 29102), is a soft-drug PDE4 inhibitor that has shown promising medicinal properties, making it a strong candidate for effective topical treatment of AD [204].

Targeting JAK-STAT pathways

Current evidence suggests that Th2 and Th22 activation in the skin and serum is crucial in AD development, particularly in the acute phase. This is often followed by Th1 (IL-γ, TNF-α) and Th17 (IL-17) activation in the chronic stage. Many of these cytokines utilize the JAK/signal transducer and activator of the transcription [JAK/signal transducer and activation of transcription (STAT)] pathway, underscoring the growing relevance of JAK inhibitors in AD treatment [189, 205, 206].

Restoring Treg cell function

In allergic conditions like AD, Tregs exhibit impaired functionality, resulting in immune dysregulation [189]. Pegylated recombinant human IL-2 has been formulated to stimulate and cause the expansion of T regulatory cells [189]. This therapeutic approach is currently under investigation in a phase Ib clinical trial [189].

Targeting the ‘psoriasis pathway’

In addition to being central to the pathogenesis of psoriasis, growing evidence suggests that the IL-23–IL-17 axis, along with IL-36, may participate in the development of specific variants of AD, particularly the intrinsic type in Asian patients [17, 207–211]. Secukinumab, an anti-IL-17A antibody, was used in two studies on AD patients (moderate to severe conditions) but was not found to be clinically efficacious in a phase II clinical study [212].

Innovative therapeutic strategies

Mesenchymal stem cell therapy with adipose-derived stem cells

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) offer promising cellular therapy for AD due to their regenerative and immunomodulatory properties [213]. Sourced from various tissues, adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) are particularly advantageous for AD treatment. ADSCs inhibit Th17 cell proliferation and activation in vitro, normalize IL-17 signaling in AD skin lesions, and epidermal hyperplasia, mast cell accumulation, and circulating IgE concentrations [32]. They also decrease inflammation markers like matrix metallopeptidase 12 (MMP-12) and CC-chemokine also called MIP-3α or macrophage inflammatory protein-3α (CCL20) in AD mouse models, with RNA sequencing confirming reduced IL-17 mRNA expression [32]. These findings highlight the potential of MSC-based therapy in treating allergic diseases [32].

Adipose-tissue-derived membrane-free stem cell extract therapy

Membrane-free stem cell extract (MFSCE) is notable for its intracellular content while lacking cell membranes, making it a promising candidate for AD therapy [33, 214]. This extract has demonstrated anti-inflammatory [214], antioxidant [215], and neuroprotective [216] effects. Notably, MFSCE influences integrin pathways, as well as inflammation and wound-healing proteins [214]. It effectively suppresses IL-1α-induced inflammatory responses, such as inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), cycloxygenase-2 (COX-2), and prostaglandin E2, by inhibiting the NFκB and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) pathways [33]. In murine AD models, MFSCE reduces serum IgE levels, TARC, and key cytokines, including IL-4, and TNF-α. Additionally, it prevents epidermal thickening and mast cell infiltration, underscoring its potential as a therapeutic option for AD.

Targeting mitochondria and its metabolism

In non-lesional AD (ADNL), increased oxidative stress and upregulated mitochondrial function were observed in the epidermis [34]. Enhanced mitochondrial activity, including increased pyruvate uptake and very long-chain fatty acid oxidation, led to higher acetyl CoA production and greater reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation in ADNL KCs [34]. Treatment of ADNL-derived human epidermal equivalents (HEEs) with MitoQ (a mitochondrial targeting molecule with ubiquinone linked to a lipophilic triphenylphosphonium cation which exhibits both metabolic and anti-oxidant properties) and TG (tigecycline, an antibiotic inhibiting oxidative phosphorylation) reduced oxidative stress markers like NFκB p65 subunit (p65-NFκB), 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE), gamma histone 2A family member X (γH2AX), malondialdehyde (MDA), and 8-Hydroxydeoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) (8-OH(d)G) while increasing corneodesmosin expression. These findings indicate that focusing on mitochondrial metabolism could offer a new avenue for therapeutic intervention in AD.

CAR-T cells targeting mIgE therapy

CAR-engineered T cells are extending their application from cancer therapy to the management of immune-mediated pathologies, including autoimmune disorders and severe allergic reactions [217]. CAR-T cells have been specifically designed to target the transmembrane form of mIgE, the exclusive B-cell antigen receptor found on all IgE-producing B cell subsets [35]. Two specialized CAR constructs target mIgE: the extracellular membrane-proximal domain (EMPD) CAR, which binds to the EMPD, a 52 amino acid sequence unique to mIgE and absent on sIgE (secreted IgE), and the alpha chain extracellular domain (ACED) CAR, which targets the ACED of the FcεRI [35]. Both in vitro and in vivo preclinical studies have demonstrated that EMPD and ACED CAR-T cells selectively target cells that express mIgE while sparing those that have passively bound secreted IgE to the Fc receptors [35].

ACT with Treg cells

Advanced technologies have enabled the application of ACT with ex vivo expanded T regulatory cells through three main strategies: (1) using polyclonal Treg cells without antigen stimulation; (2) expanding Treg cells with antigen stimulation; and (3) genetically engineering Treg cells with a CAR. These regulatory-based adoptive cell therapies include autologous polyclonal Treg cells, antigen-stimulated Treg cells, and genetically engineered Treg cells [36].

Future perspectives: advancing research, diagnosis, and therapeutics for AD

Despite significant advances in understanding AD, several critical gaps remain that hinder the development of more effective therapies. These gaps highlight the need for continued research and innovation in the field. One major challenge is the incomplete mechanistic understanding of AD. While the role of genetic factors, such as FLG mutations, in AD pathogenesis is well-established, the precise mechanisms through which these mutations interact with environmental triggers and immune responses are not fully understood. The complexity of the disease’s pathogenesis, including the interplay of genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors, remains a significant barrier to developing targeted therapies.

AD shows significant variability in both clinical presentation and severity among different individuals and populations. This variability complicates diagnosis and treatment, as a one-size-fits-all approach may not be effective. Understanding the reasons behind this variability, including differences in genetic backgrounds, environmental exposures, and immune system responses, is crucial for tailoring personalized treatment strategies.

Furthermore, although the involvement of various immune cells and cytokines in AD is recognized, the detailed interactions among these components and their exact roles in disease progression are not fully elucidated. This gap in knowledge limits the ability to develop therapies that specifically target the underlying immune dysfunctions in AD. While several biomarkers, such as total serum IgE and FLG levels, are used in assessing disease severity and treatment response, there is a need for more reliable and specific biomarkers. Current biomarkers may not adequately reflect the complexity of the disease or its response to therapy, underscoring the need for novel biomarkers that can better guide diagnosis and treatment.

Existing treatments for AD, including topical corticosteroids and immunomodulators, provide symptomatic relief but often fail to address the root causes of the disease or provide long-term solutions. The development of novel therapeutic approaches that target specific disease mechanisms or restore barrier function is essential for improving patient outcomes.

Addressing the gaps in our current understanding of AD requires innovative approaches at both the bench and clinical levels. The following future perspectives aim to bridge these gaps and advance the development of effective therapies.

Mechanistic research and target identification

To advance the understanding and treatment of AD, mechanistic research and target identification must focus on genetic and epigenetic exploration. Detailed studies on FLG mutations and other genetic factors are essential to elucidate their roles in AD pathogenesis and their interactions with environmental triggers. Advanced genomic and epigenomic analyses can reveal how these genetic variations contribute to disease development. Additionally, leveraging integrated omics technologies—including genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—can offer a thorough understanding of the molecular pathways associated with AD. This holistic approach will likely uncover novel therapeutic targets and identify specific biomarkers associated with different AD phenotypes, enhancing diagnostic precision and enabling personalized treatment strategies.

Personalized and precision medicine

To address the variability in AD presentation, future research should prioritize characterizing disease subtypes based on genetic, environmental, and immune profiles. Understanding these subtypes will facilitate the development of personalized treatment regimens tailored to individual patient profiles. By incorporating data from precision medicine studies, such as genomic and proteomic analyses, researchers can create customized therapeutic strategies that target specific aspects of the disease in each patient. This approach aims to enhance treatment efficacy and improve patient outcomes by addressing the unique characteristics of AD.

Immune mechanisms and novel targets

Comprehensive studies of immune cell interactions and cytokine networks in AD are needed to clarify their roles in disease progression, which could potentially uncover novel immune targets for therapeutic intervention. Research into advanced immunomodulatory therapies, such as targeted biologics and small molecules, should be prioritized to specifically address the immune dysregulation seen in AD. By gaining a deeper understanding of detailed immune profiling, these innovative treatments can be developed to precisely modulate the immune response, offering more effective and tailored therapeutic options for AD patients.

Biomarker development and validation

Efforts should be directed toward discovering and validating new biomarkers that can better reflect disease activity, severity, and treatment response in AD, including those related to barrier dysfunction, immune activation, and inflammation. Developing robust, clinically applicable biomarker panels can enhance diagnostic accuracy and allow for better monitoring of treatment efficacy and disease progression. This integration of novel biomarkers into clinical practice will facilitate personalized treatment approaches and improve patient outcomes by providing a more precise understanding of the disease state and therapeutic responses.

Innovative therapeutic approaches

Despite the availability of current medications for AD, such as topical corticosteroids and immunomodulators, these treatments often provide only symptomatic relief and may fail to address the underlying causes of the disease or offer long-term solutions. This highlights the necessity for exploring advanced therapies, such as CAR-T cell therapy, stem cell therapy, and regenerative medicine. These innovative approaches promise substantial long-term benefits by targeting the root causes of AD, including immune system imbalances and disruptions in the epidermal barrier. CAR-T cell therapy, for instance, has the potential to provide precise and durable immune modulation, while stem cell therapy and regenerative medicine could restore and repair the damaged skin barrier, leading to sustained remission and improved quality of life for patients. Investing in these advanced therapies represents a forward-thinking strategy to achieve more effective, comprehensive, and lasting treatment outcomes for AD, ultimately reducing the disease burden and enhancing patient well-being.

By focusing on these areas, future research can advance our understanding of AD, leading to more effective, personalized, and innovative treatment options for patients. Addressing these specific gaps will be crucial for overcoming current limitations and improving outcomes for individuals suffering from AD.

Conclusions

This review examines the complex etiopathogenetic factors affecting AD, highlighting the impact of various environmental stressors on shaping the disease phenotype. A critical aspect of effective management is the revitalization of the compromised epidermal barrier and the reduction of TEWL through advanced, targeted novel therapeutic approaches, such as cell-based therapies, that aim to expand the horizon of positive outcomes, and position AD at the forefront of the cutting-edge dermatological research. Concurrently, immunomodulatory treatments remain essential, with traditional agents like topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors continuing to be pivotal due to their proven efficacy and broad clinical acceptance. JAK inhibitors offer prompt relief from itching and inflammation but raise ongoing concerns regarding their benefit-risk profile, necessitating vigilant pharmacovigilance. When used early in the disease progression, these agents may act as disease modifiers, potentially influencing the atopic march and related comorbidities. The introduction of biologics, particularly dupilumab, which inhibits IL-4 and IL-13 signaling pathways, signifies a transformative advancement in managing mild-to-extreme AD conditions. However, the effectiveness of these therapies is highly dependent on patient adherence and education, with strict adherence to treatment protocols and avoidance of environmental triggers being crucial for achieving optimal results. Additionally, lifestyle modifications, including proper skin care practices and avoidance of known irritants, are essential adjuncts to pharmacotherapy.

Abbreviations

| ACED: | alpha chain extracellular domain |

| ACT: | adoptive cell therapy |

| AD: | atopic dermatitis |

| ADNL: | non-lesional atopic dermatitis |

| ADSCs: | adipose-derived stem cells |

| AMPs: | antimicrobial peptides |

| aSMase: | acid sphingomyelinase |

| CAR: | chimeric antigen receptor |

| CCL17: | C-C motif chemokine ligand 17 |

| CerS3: | ceramide synthase 3 |

| DCs: | dendritic cells |

| EDC: | epidermal differentiation complex |

| EH: | eczema herpeticum |

| Elovl1: | elongation of very long chain fatty acids |

| EMPD: | extracellular membrane-proximal domain |

| ER: | endoplasmic reticulum |

| FcεRI: | high-affinity immunoglobulin E receptor |

| FFAs: | free fatty acids |

| FLG: | filaggrin |

| GBA: | β-glucocerebrosidase |

| GBD: | global burden disease |

| hBD-3: | human β-defensin 3 |

| HDMs: | house dust mites |

| HSV: | herpes simplex virus |

| IDECs: | inflammatory dendritic epidermal cells |

| IFN-γ: | interferon-gamma |

| IgE: | immunoglobulin E |

| IL-8: | interleukin-8 |

| ILC2: | type 2 innate lymphoid cells |

| JAK: | Janus kinase |

| KC: | keratinocyte |

| KLK: | kallikrein |

| KRT: | keratin |

| LCs: | Langerhans cells |

| LEKTI: | lympho-epithelial Kazal-type-related inhibitor |

| MABp1: | bermekimab |

| MFSCE: | membrane-free stem cell extract |

| mIgE: | membrane-bound immunoglobulin E |

| MSCs: | mesenchymal stem cells |

| NFκB: | nuclear factor kappa B |

| NMFs: | natural moisturizing factors |

| OAS1: | 2’,5’-oligoadenylate synthetase 1 |

| PCA: | pyrrolidine carboxylic acid |

| pDC: | plasmacytoid dendritic cell |

| PDE4: | phosphodiesterase 4 |

| PM: | particulate matter |

| PN: | prurigo nodularis |

| Pro-FLG: | profilaggrin |

| R. mucosa: | Roseomonas mucosa |

| S. aureus: | Staphylococcus aureus |

| S100A7: | S100 calcium-binding protein A7 |

| SB: | stratum basale |

| SC: | stratum corneum |

| SG: | stratum granulosum |

| ShA9: | Staphylococcus hominis A9 |

| SL: | stratum lucidum |

| SPINK5: | Kazal-type 5 serine protease |

| SS: | stratum spinosum |

| STAT: | signal transducer and activation of transcription |

| TARC: | thymus and activation-regulated chemokine |

| TEWL: | transepidermal water loss |

| Th2: | T helper cell type 2 |

| TJ: | tight junction |

| TLR2: | Toll-like receptor 2 |

| TNF-α: | tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| Tregs: | regulatory T cells |

| TRPV1: | transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 |

| TSLP: | thymic stromal lymphopoietin |

| UCA: | urocanic acid |

| VOC: | volatile organic compounds |

Declarations

Author contributions

AB: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. UM: Validation, Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Supervision. Both authors read and approved the submitted version.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

We would like to acknowledge the funds provided by CSIR [MLP137-MISSION LUNG] and DST SERB [GAP-432]. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

Publisher’s note

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.