Abstract

Aim:

Modification of the C-terminus of a peptide to improve its properties, particularly after constructing the peptide chain, has great promise in the development of peptide therapeutics. This study discusses the development of a late-stage diversification method for synthesizing peptide acids and amides from hydrazides which can serve as a common precursor.

Methods:

Peptide hydrazides were synthesized solely by using conventional solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS). Hydrazides were subjected to oxidation by potassium peroxymonosulfate (Oxone) to afford carboxylic acids. Azidation of hydrazides using sodium nitrite (NaNO2) under acidic conditions, followed by the addition of β-mercaptoethanol (BME), could also be used to generate carboxylic acids. For the preparation of peptide amides, azides that can be prepared from hydrazides were reacted with ammonium acetate (NH4OAc) or tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP)∙hydrochloride (HCl) to develop the products through ammonolysis or a Staudinger reaction, which produces iminophosphorane from an azide and a phosphine. The antimicrobial activity of modelin-5 derivatives synthesized from the corresponding hydrazides was evaluated by the colony count of Escherichia coli (E. coli) after treatment with the peptides.

Results:

Oxone oxidation yielded the corresponding acids rapidly although oxidation-prone amino acids were incompatible. Azidation and subsequent treatment with BME afforded peptide acids an acceptable yield even in sequences containing amino acids that are prone to oxidation. Both methods for conversion of hydrazides to amides were found to afford the desired products in good yield and compatibility. The conditions that were developed were adapted to the synthesis of modelin-5 derivatives from the corresponding hydrazides, yielding late-stage production of the desired peptides. The amides of the resulting peptide showed more potent activity against E. coli than the acid form, and the most potent activity was observed from the hydrazide.

Conclusions:

The developed protocols allow hydrazides to be converted to acids or amides, enabling late-stage diversification of peptide C-terminal residues.

Keywords

Late-stage diversification, peptide hydrazide, peptide acid, peptide amide, antimicrobial peptideIntroduction

Peptide therapeutics play a role in drug development because of the unique properties of peptides, which include high specificity, good efficacy, and low immunogenicity when compared to small molecule drugs and biologics [1, 2]. To develop a peptide-based drug, chemical peptide synthesis and subsequent modifications on the sequence and terminal structures are steps that are essential to improve its pharmacological properties after the first step, the discovery of potential peptide therapeutics.

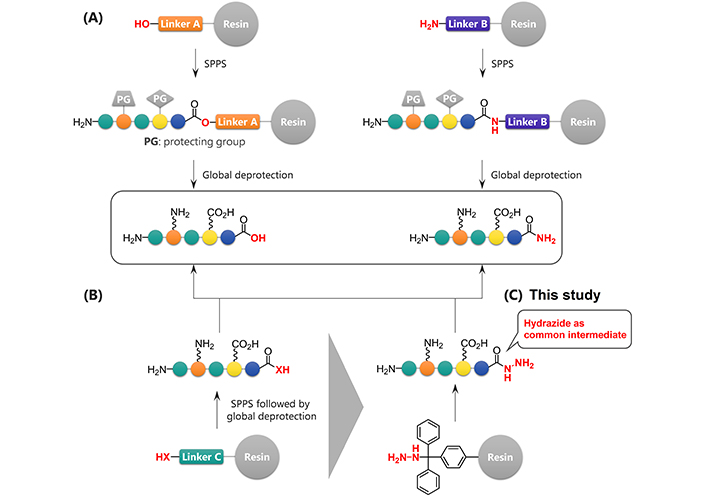

Modification of the C-terminus of a peptide can significantly affect its bioactivity, stability, or three-dimensional conformations [3]. Even relatively minor structural changes, such as α-amidation of the C-terminal moiety, often significantly affect the peptide properties. For this reason, many strategies to access C-terminally modified peptides have been developed. The most widely used strategy is based on the selection of linkers prior to solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) [4, 5]. This is a reliable strategy but the desired functional groups must be incorporated at the beginning of the synthesis because the peptides are usually synthesized beginning at the C-terminus (Figure 1A). Therefore, this type of strategy requires a significant synthetic effort to create a peptide library containing diverse C-terminal residues.

Synthesis of C-terminally modified peptides. (A) Synthesis of C-terminally modified peptides using different linkers; (B) late-stage diversification of C-terminally modified peptides; (C) hydrazide-mediated late-stage synthesis of carboxylic acids or amides

Late-stage modification strategies, which can lead to new analogs of a parent structure, have been recognized as useful methods that may allow the performance of only a single SPPS to construct the peptide sequence and complete the subsequent transformation of its C-terminus to generate various analogs (Figure 1B). The key to the success of this strategy in peptides is achieving the chemoselective and site-selective transformation, particularly in the absence of any protecting groups on reactive functional groups. Consequently, hydrazide was used as a chemoselective handle at the C-terminus (Figure 1C). This study focused on transforming hydrazides to carboxylic acids and amides because both of these C-terminal structures are common in bioactive peptides, often significantly affecting their structure and activity. Oxidation of a hydrazide will convert it to a carboxylic acid [6–10]. Treatment with β-mercaptoethanol (BME) can generate peptide acids from the corresponding thioesters, which can be prepared from unprotected hydrazides [11–13]. Ammonolysis [14] or the Staudinger reaction [15] of the peptide azides which in turn can be prepared from hydrazides are two potential methods for the preparation of peptide amides. Here a systematic and comprehensive evaluation of the relevant transformations is described and their utility by synthesizing modelin-5 derivatives including an artificial antimicrobial peptide is demonstrated [16].

Materials and methods

Materials

All commercially available reagents and protected amino acids were purchased and used without further purification. Rink amide ChemMatrix, trityl (Trt)-OH ChemMatrix, and HMPB ChemMatrix were purchased from Biotage Japan Ltd. Dry dichloromethane (DCM), dry N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), methanol (MeOH), sodium nitrite (NaNO2), disodium hydrogen phosphate, copper (II) sulfate, 5-hydrate (CuSO4∙5H2O), N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA), and ammonium acetate (NH4OAc) were purchased from KANTO Chemical Co., Inc. 9-Fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl (Fmoc) carbazate, 2-iodoxybenzoic acid (IBX), N-bromosuccinimide (NBS), trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), triisopropylsilane (TIS), BME, 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP), piperidine, and m-cresol were purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. DMF, diethyl ether (Et2O), acetonitrile (CH3CN), potassium peroxymonosulfate (Oxone) and tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP)∙hydrochloride (HCl) were purchased from Fuji Film Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd. Thioanisole, lysogeny broth (LB), Miller, and guanidine (Gn)∙HCl were purchased from NACALAI Tesque, Inc. N,N’-Diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIPCI) and Fmoc-D-alanine (Ala)-OH∙H2O were purchased from Watanabe Chemical Industries Ltd. Ethyl cyanohydroxyiminoacetate (OxymaPure) was purchased from Merck KGaA. Thionyl chloride was purchased from Kishida Chemical Co., Ltd. Fmoc-L-Ala-OH∙H2O and Fmoc-methionine (Met)-OH were purchased from Bachem AG. Fmoc-cysteine (Cys)(Trt)-OH, Fmoc-glutamic acid (Glu)(Ot-Bu)-OH, Fmoc-phenylalanine (Phe)-OH, Fmoc-glycine (Gly)-OH, Fmoc-histidine (His)tert-butoxycarbonyl (Boc)-OH, Fmoc-isoleucine (Ile)-OH, Fmoc-lysine (Lys)(Boc)-OH, Fmoc-leucine (Leu)-OH, Fmoc-proline (Pro)-OH, Fmoc-arginine (Arg)2,2,4,6,7-pentamethyldihydrobenzofuran-5-sulfonyl (Pbf)-OH, Fmoc-serine (Ser)(t-Bu)-OH, Fmoc-threonine (Thr)(t-Bu)-OH, Fmoc-valine (Val)-OH, Fmoc-tyrosine (Tyr)(t-Bu)-OH, and Fmoc-tryptophan (Trp)(Boc)-OH were purchased from CEM corporation. Fmoc-Cys acetamidomethyl (Acm)-OH was purchased from Peptide Institute, Inc.

LCMS and preparative HPLC

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LCMS) analyses were carried out on a Waters Alliance high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system with Acquity single quadrupole (SQ) Detector (ESI-SQ). For HPLC separations, a Cosmosil 5C18-AR-II analytical column (Nacalai Tesque, 4.6 mm × 250 mm, flow rate 1.0 mL/min) and a Cosmosil 5C18-AR-II preparative column (Nacalai Tesque, 20 mm × 250 mm, flow rate 8.0 mL/min) were employed, and the eluted products were detected by ultra-violet (UV) at 220 nm. A solvent system consisting of 0.1% TFA aqueous solution (aq; v/v, solvent A) and 0.1% TFA in CH3CN (v/v, solvent B) was used for HPLC elution.

Synthesis of model peptide hydrazides, H-LYRA-Xaa-NHNH2 (1a–q)

The hydrazine-incorporated resin was prepared using previously reported methods [17]. Trt-OH ChemMatrix resin was swollen in dry DCM and treated with thionyl chloride (10 equiv) at room temperature (rt) for 2 h. After being washed with dry DCM and dry DMF, the resulting resin was swollen in dry DCM. To the resin was added a solution of Fmoc carbazate (4 equiv) and DIPEA (10 equiv) in dry DMF (same volume as DCM) dropwise at 0℃. The reaction mixture was shaken at rt overnight, then MeOH was added. After 10 min, the resin was filtered and washed successively with DMF, water, DMF, MeOH, and Et2O. The loading was confirmed by quantification of the Fmoc group [18].

A manual synthesis of Fmoc-SPPS was conducted as follows: (coupling) Fmoc-protected amino acid, OxymaPure, and DIPCI (4 equiv each) were reacted in DMF (0.3 mol/L), 1 h, rt; (Fmoc removal) was achieved with 20% (v/v) piperidine in DMF for 10 min at rt. After the elongation, the resulting resin was treated with TFA-TIS-H2O [95:2.5:2.5 (v/v), 50 μL/1 mg resin) at rt. After 2 h, Et2O was added to the mixture to give a precipitate which was collected by centrifugation and thoroughly washed with Et2O. The LCMS data of the crude materials are shown in Figures S1–18.

Oxidative conversion of hydrazides

The elongated resin containing 1 (5 mg, approximately 1.5 μmol) was deprotected through the protocol described above and the resulting crude material was dissolved in 50% CH3CN-H2O (200 μL) containing an oxidant (30 µmmol, 20 equiv of CuSO4∙5H2O; 7.5 µmmol, 5.0 equiv for Oxone, IBX, and NBS), and the mixture was allowed to react at rt. The reaction progress was monitored by LCMS (Figures S19–37).

BME-mediated conversion of hydrazides

The resin of elongated 1 (5 mg, approximately 1.5 µmol) was deprotected through the protocol described above. The resulting crude material was dissolved in 300 µL of a low pH buffer (6 mol/L Gn∙HCl, 0.2 mol/L Na phosphate, pH 3), then 30 µL of 0.5 mol/L NaNO2 in a low pH buffer was added to the solution at –10℃ [19]. After 30 min reaction at –10℃, 1 mol/L BME in a high pH buffer (6 mol/L Gn∙HCl, 0.2 mol/L Na phosphate, pH 8, 300 µL) was added to the mixture. The pH was adjusted to pH 8.9 and the reaction was allowed to stand for 30 min at rt. The reaction progress was analyzed by LCMS (Figures S38–54).

Ammonolysis of peptidyl azides derived from hydrazides

The resin of elongated 1 (5 mg, approximately 1.5 µmol) was deprotected through the protocol described above. The resulting crude material was dissolved in 40 µL of a low pH buffer (6 mol/L Gn∙HCl, 0.2 mol/L Na phosphate, pH 3), then 10 µL of 1 mol/L NaNO2 aq was added to the mixture at –10℃. After 30 min reaction at –10℃, 8 mol/L NH4OAc (pH 8.3, 150 µL) was added to the mixture. The reaction was allowed to stand for 30 min at rt and the reaction progress was analyzed by LCMS (Figures S55–72).

Amidation of peptidyl azides by the Staudinger reaction

The reaction via azidation in an acidic aq was performed as follows. The resin of elongated 1 (5 mg, approximately 1.5 µmol) was deprotected using the method described above, and the resulting crude material was dissolved in a low pH buffer (6 mol/L Gn∙HCl, 0.1 mol/L phosphate, pH 3, 100 µL). To the solution was added 10% (w/w) NaNO2 aq (5 µL) at –10℃. After 30 min at –10℃, 100 µL of phosphate buffer (0.1 mol/L, 6 mol/L Gn∙HCl, 0.2 mol/L TCEP∙HCl, pH 3) was added. The mixture was allowed to react for 30 min at rt, the reaction progress being analyzed by LCMS (Figures S73–90).

The azidation in TFA solution was performed as follows (Figure S91 and Table S1) [20]. The resin bearing elongated 1 (5 mg, approximately 1.5 µmol) was treated with TFA-TIS-H2O-m-cresol-thioanisole [80:2.5:2.5:5:10 (v/v), 50 µL/1 mg resin] at rt. After a 2-h reaction, 10% (w/w) NaNO2 aq (5 µL) was added to the mixture at –10℃. The solution was allowed to react for 30 min at –10℃ and then cold Et2O was added to give a precipitate. This crude product was dissolved in 50% CH3CN-H2O (200 µL) containing TCEP·HCl (2 equiv) and the mixture was allowed to stand at rt for 30 min. The reaction progress was analyzed by LCMS (Figures S92–109).

Evaluation of epimerization

To monitor the epimerization, the amino acids were coupled by DIPCI and DMAP for carboxylic acids or Rink amide ChemMatrix resin for amides. Then, epimers with C-terminal D-amino acids were synthesized by standard manual Fmoc SPPS. The resulting epimers were used to determine the HPLC conditions for the separation (Figures S110 and 111).

Synthesis of modelin-5 derivatives

Hydrazide-incorporated resin (0.31 mmol/g) was used for the preparation of the hydrazide (9). On this resin, the peptide was elongated using an automated Fmoc SPPS procedure with a Biotage Initiator+ Alstra peptide synthesizer with a 10 mL open-type vial, coupling with Fmoc-protected amino acids, OxymaPure, and DIPCI (4 equiv each) in DMF (0.5 mol/L), for 5 min at 75℃ under microwave irradiation; Fmoc removal was accomplished with 20% (v/v) piperidine in DMF for 3 min at 50℃ under microwave irradiation. The resulting resin was treated with TFA-TIS-H2O [95:2.5:2.5 (v/v); 50 μL/1 mg resin] at rt for 2 h. The resin in the reaction mixture was removed by filtration and then the filtrate was concentrated in a stream of air. The crude product was dissolved in 0.1% TFA aq (3 mL) and the aqueous phase was washed with Et2O. The crude peptide was purified by preparative HPLC with a linear gradient of solvent B in solvent A, 22–32% over 60 min to give the peptide hydrazide (9; 20 mg from 103 mg of protected resin, 34% isolated yield, Figure S112).

For the preparation of the peptide acid (10), the crude 9, prepared as described above (from 102 mg of protected resin, 23 µmol) was dissolved in 3 mL of 50% CH3CN-H2O with Oxone (116 µmol, 5 equiv), after which the solution was incubated at 37℃ for 30 min. The crude peptide was purified by preparative HPLC with a linear gradient of solvent B in solvent A, 22–32% over 60 min to give the purified peptide (10; 18 mg, 32% isolated yield, Figure S113).

For the preparation of the peptide amide (11), the crude 9, prepared from 99 mg (23 µmmol) of protected resin, as described above was dissolved in 1.5 mL of 6 mol/L Gn∙HCl, 0.1 mol/L phosphate (pH 3). After the addition of 0.1 mL of 10% (w/w) NaNO2 aq at –10℃, the mixture was allowed to react for 30 min at the same temperature. To the solution was added 1.5 mL of a phosphate buffer (0.1 mol/L, 6 mol/L Gn∙HCl, 0.2 mol/L TCEP·HCl, pH 3), and then the reaction mixture was incubated at rt for 30 min. The crude peptide was purified by preparative HPLC with a linear gradient of solvent B in solvent A, 22–32% over 60 min to give the peptide amide (11; 21 mg, 37% isolated yield, Figure S114).

Evaluation of antimicrobial activity

Escherichia coli (E. coli) W3110 [21] was grown on LB [1% (w/v) tryptone, 0.5% (w/v) yeast extract, and 1% (w/v) NaCl] containing 1.5% agar, and colonies were inoculated in 5 mL LB medium at 200 rpm at 37℃ for approximately 4 h (OD600 = 1.6). The bacterial cells were collected by centrifugation (6,000 × g, 10 min, 4℃) and washed with 1 mL of a 25% strength Ringer’s solution three times through centrifugation (6,000 × g, 5 min, 4℃). The bacterial cells were suspended with Ringer’s solution and diluted to adjust the OD600 to 0.5. A 100 µL sample of the resulting suspensions was mixed with 100 µL of synthesized modelin-5 derivatives (9–11) in Ringer’s solution to give a final peptide concentration of 500 µmol/L. This mixture was incubated in an orbital shaker (100 rpm, 37℃) for 1 h. The bacterial suspension was inoculated onto LB agar plates and incubated at 37℃. After 14 h incubation, the colony forming unit (CFU) was calculated.

Results

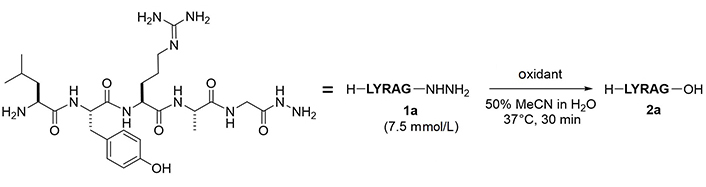

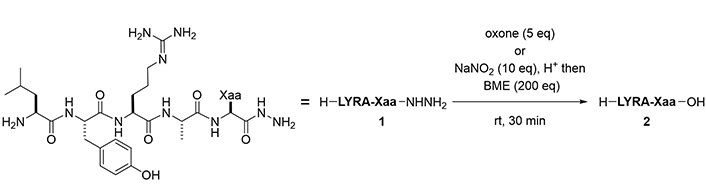

To examine the feasibility of converting peptide hydrazides to carboxylic acids, the model peptide (H-LYRAG-NHNH2, 1a) was treated with several oxidants (Figure 2 and Table 1). Although copper (II) sulfate (CuSO4) was effective in converting an N-alkyl hydrazide peptide to carboxylic acid [6, 7], it produced the corresponding carboxylic acid (2a) only in a low yield (entry 1). Oxone oxidation proceeded smoothly within 30 min (entry 2). Treatment with IBX or NBS consumed the starting material but failed to generate the desired product (entries 3 and 4). The plausible mechanism of Oxone-mediated transformation of hydrazides to acids is given in Figure 3 [22].

Optimization of oxidant

| Entry | Oxidant | Equiv | pH | HPLC purity of 2a (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CuSO4∙5H2O | 20 | 3.8 | 11 |

| 2 | Oxone | 5 | 2.1 | 93 |

| 3 | IBX | 5 | 1.8 | < 1 |

| 4 | NBS | 5 | 4.4 | < 1 |

a detected at 220 nm

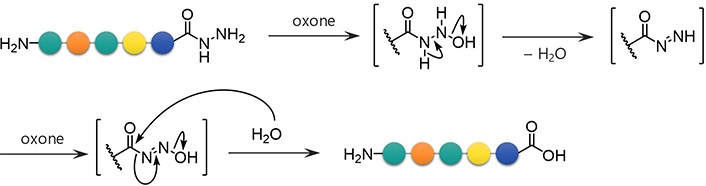

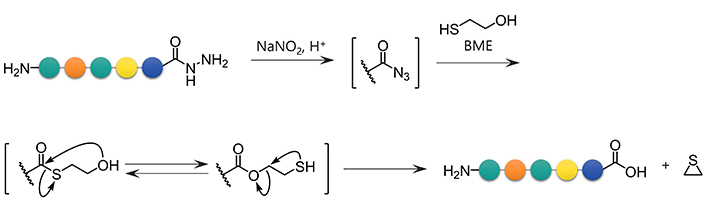

Formation of azides from hydrazides followed by a reaction with BME is another approach for the conversion of hydrazides to carboxylic acids. Unprotected hydrazides can be transformed into peptidyl azides with the aid of NaNO2 under acidic conditions. In the presence of thiols [19], azides readily afford the corresponding thioesters. Thioesters of BME are formally hydrolyzed through the intramolecular S-to-O acyl transfer followed by thiirane formation, releasing the appropriate carboxylate (Figure 4) [11]. This reaction sequence has been used for the epimerization-free synthesis of peptide acids with a C-terminal Cys [12], but has not been systematically and comprehensively evaluated.

BME-mediated formal hydrolysis of peptidyl azides preparable from unprotected hydrazides

To evaluate the scope of these two methods to generate carboxylic acids, peptide hydrazides bearing amino acids at the C-terminus were prepared. The exceptions were aspartic acid (Asp), asparagine (Asn), and glutamine (Gln) because of the synthetic difficulty due to intramolecular cyclization [19]. Using oxidation by Oxone, the desired carboxylic acids were obtained with 63–87% purity (Figure 5, Table 2). Oxidation-prone amino acids, namely Cys, Met, and Trp, were however incompatible with this condition. A separate protocol using BME after azide formation succeeded in the transformation of hydrazides to the corresponding carboxylic acids in 60–95% yield. Ile and Pro required a longer reaction time to completely convert the intermediate thioester to the acid (entries 4 and 7). Unlike the reaction conditions of the Oxone reaction, the BME-mediated reaction was applicable to the peptides with C-terminal Cys, Met, or Trp (entries 11, 13, and 18). The epimerization of C-terminal amino acids (Ala) was suppressed during the reactions (epimer ratio > 99:1, Figure S110).

Scope of the C-terminal amino acids in conversion to carboxylic acids

| Entry | Xaa | Product | HPLC purity of 2 (%)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxone | BME | |||

| 1 | Gly | 2a | 84 | 82 |

| 2 | Ala | 2b | 82 | 82 |

| 3 | Val | 2c | 77 | 76 |

| 4 | Ile | 2d | 63 | 61 (74)b |

| 5 | Leu | 2e | 80 | 79 |

| 6 | Phe | 2f | 87 | 89 |

| 7 | Pro | 2g | 77 | 65 (87)b |

| 8 | Ser | 2h | 82 | 81 |

| 9 | Thr | 2i | 81 | 91 |

| 10 | Glu | 2j | 81 | 95 |

| 11 | Cys | 2k | < 1 | 66 |

| 12 | Cys(Acm) | 2k’ | < 1 | - |

| 13 | Met | 2l | < 1 | 80 |

| 14 | Tyr | 2m | 81 | 87 |

| 15 | His | 2n | 81 | 85 |

| 16 | Lys | 2o | 76 | 75 |

| 17 | Arg | 2p | 84 | 60 |

| 18 | Trp | 2q | < 1 | 86 |

a detected at 220 nm; b after the addition of BME, a 20 h reaction was performed. -: not examined

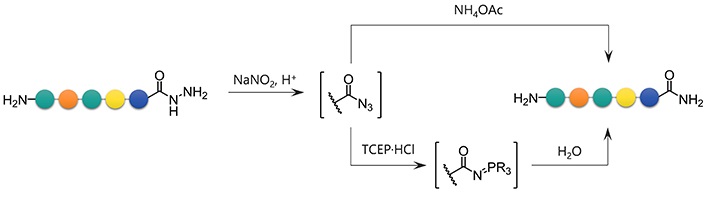

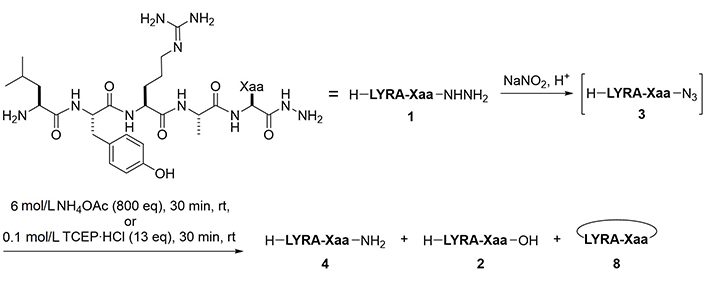

To convert a peptide hydrazide to the peptide amide, two methods were used: 1) Azidation followed by ammonolysis, and 2) azidation followed by the Staudinger reaction (Figure 6). After preliminary experiments, peptide amides were found to be formed by ammonolysis of peptidyl azides using 6 mol/L NH4OAc in a slightly basic buffer. Similarly, the Staudinger reaction of peptidyl azides using 0.1 mol/L TCEP·HCl as a water-soluble phosphine gave the desired amide within 30 min.

With the optimal conditions in hand, the scope of these conditions with respect to various C-terminal amino acids was examined (Figure 7 and Table 3). In the NH4OAc-mediated ammonolysis, the desired amides (4) were obtained together with the hydrolyzed products (2) and compounds with molecular weight 17 less than these, probably because of the intramolecularly cyclized peptides (8). In the case of C-terminal Glu and His, significant amounts of the hydrolyzed peptide (2) were obtained (entries 10 and 15). The peptide with a C-terminal Cys residue afforded a low yield because of the formation of a disulfide-related byproduct, which was suppressed by using Acm protection for the thiol (entries 11 and 12).

Scope of the C-terminal amino acids in conversion to amides

| Entry | Xaa | Product | HPLC purity (%)a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ammonolysis | Staudinger reaction | ||||||

| 4 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 2 | |||

| 1 | Gly | 2a | 86 | 5 | 6 | 94 | 6 |

| 2 | Ala | 2b | 80 | 4 | 9 | 84 | 7 |

| 3 | Val | 2c | 82 | 2 | 8 | 91 | 1 |

| 4 | Ile | 2d | 91 | < 1 | < 1 | 92 | < 1 |

| 5 | Leu | 2e | 74 | 5 | 13 | 94 | 4 |

| 6 | Phe | 2f | 87 | 6 | < 1 | 91 | 6 |

| 7 | Pro | 2g | 90 | 1 | 4 | 86 | 2 |

| 8 | Ser | 2h | 79 | 3 | 9 | 93 | 4 |

| 9 | Thr | 2i | 71 | 3 | 13 | 91 | 3 |

| 10 | Glu | 2j | < 1 | 77 | < 1 | 4 (74)b | 87 |

| 11 | Cys | 2k | 39c | < 1 | < 1 | 26 | 7 |

| 12 | Cys(Acm) | 2k’ | 75 | 9 | 10 | 93 | < 1 |

| 13 | Met | 2l | 80 | 6 | 9 | 87 | 4 |

| 14 | Tyr | 2m | 83 | 8 | 2 | 85 | 5 |

| 15 | His | 2n | 45 | 39 | 4 | 68 (83)b | 28 |

| 16 | Lys | 2o | 86 | 5 | 6 | 87 | 6 |

| 17 | Arg | 2p | 91 | 6 | < 1 | 91 | 5 |

| 18 | Trp | 2q | 82 | 8 | < 1 | 80 | 8 |

a detected at 220 nm; b azidation was performed in TFA solution instead of acidic aqueous condition; c disulfide dimer of 2k was observed

The procedure using the Staudinger reaction also proceeded smoothly, yielding the peptide amides (4) in acceptable yields (80–94%) except for sequences containing Glu-, His-, or Cys-. Glu- or His-containing peptides afforded a low yield of the desired products, but 87% and 28% of the hydrolyzed product (2) were observed (entries 10 and 15). When performing the azide formation in a TFA cocktail [20] instead of under aqueous conditions, the hydrolysis was suppressed, giving the desired amides in 74% for Glu and 83% for His. The thiol group of Cys-containing peptide was oxidized to the sulfinic acid while the side reaction was suppressed using Cys(Acm) as with the ammonolysis condition (entries 11 and 12). Azidation in TFA followed by the Staudinger reaction was also effective in generating the corresponding amides from hydrazides, but in some cases, amines, oxazolidinones, or thiazolidinones were observed as a main byproduct formed through Curtius rearrangement followed by hydrolysis or cyclization of the resulting isocyanate (Table S1). The peptides having Ala at the C-terminus showed no epimerization in the transformation to amides (epimer ratio > 99:1, Figure S111).

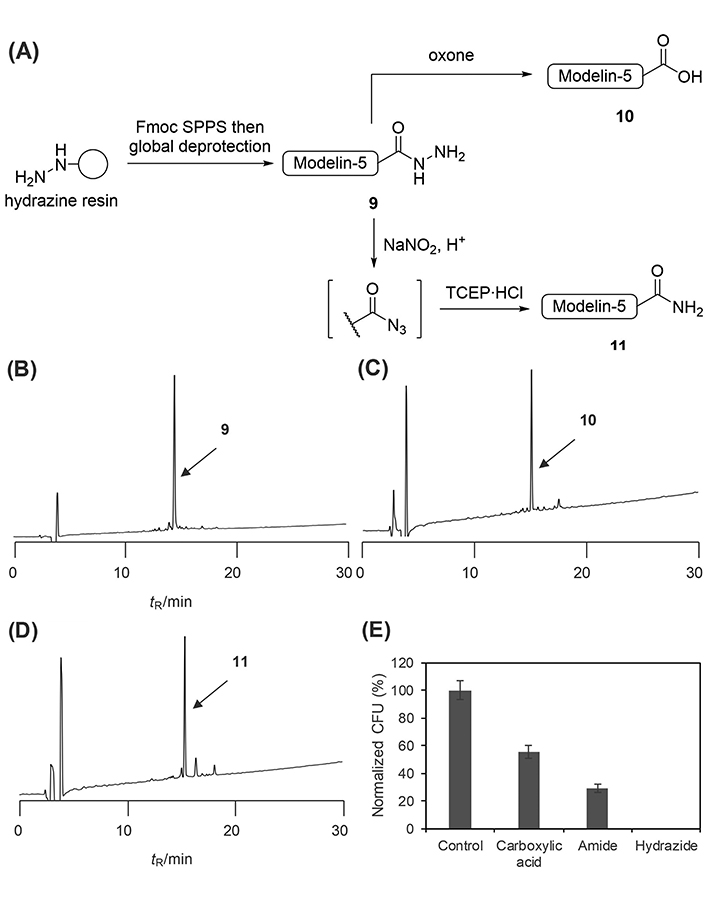

The applicability of the developed late-stage diversification strategies was validated by synthesizing modelin-5 derivatives (H-KLAKKLAKLAKLAKAL-X; X = OH, NH2, or NHNH2), an artificial antimicrobial peptide (Figure 8A). Modelin-5 is known to have varied antimicrobial potencies depending on its C-terminal structure; in particular, modelin-5-CONH2 is more potent than modelin-5-COOH [23]. The modelin-5 sequence was elongated on a hydrazine-incorporated resin through the conventional Fmoc SPPS. The standard cleavage of the elongated peptide afforded the modelin-5-CONHNH2 (9) in 34% isolated yield (Figure 8B). The global deprotection of the peptidyl resin followed by oxidation by Oxone smoothly yielded the modeline-5-COOH (10) in 32% isolated yield from the resin loading (Figure 8C). The modelin-5-CONH2 (11) was synthesized in 37% yield through the azidation of the corresponding hydrazide followed by the Staudinger reaction (Figure 8D).

Synthesis and evaluation of modelin-5 derivatives. (A) Synthetic scheme of modelin-5 derivatives from hydrazide; crude HPLC charts of (B) modelin-5-CONHNH2; (C) modeline-5-COOH; or (D) modelin-5-CONH2; (E) antimicrobial activity of modelin-5 derivatives against E. coli. Error bars represent the standard deviation (n = 3). Retention time (tR): 14.5 min for peptide hydrazide (9), 15.1 min for peptide acid (10), and 15.4 min for peptide amide (11). HPLC conditions: Cosmosil 5C18-AR-II analytical column with the linear gradient of MeCN/0.1% aqueous TFA (10:90–60:40 over 30 min) at flow rate 1.0 mL/min, detected at 220 nm.

Finally, the antimicrobial potency against E. coli of the synthesized modelin-5 derivatives was evaluated. The cells were incubated with 500 μmol/L of each peptide derivative for 1 h. The treated cells were plated and then incubated at 37℃ for 14 h, after which the number of colonies was counted (Figure 8E). As has been reported [23], the potency of the amide derivative (11) was higher than that of the carboxylic acid (10). Surprisingly, the hydrazide-type derivative (9) showed the most potent antimicrobial activity against E. coli but the mechanism that underlies such potency differences was unclear.

Discussion

Derivatization of peptides is an important method to control and improve their properties. Modification of the C-terminus of bioactive peptides has important implications for their potency. Late-stage diversification is a practical concept to create libraries with diversity, although it requires a chemoselective toolbox to apply it to peptides because peptides have various types of functional groups. In this study, simple and practical protocols were developed for the late-stage transformation of peptide C-terminus residues from hydrazides to the corresponding peptide acids and amides. Oxone oxidation yielded carboxylic acids directly from hydrazides without any additional transformations although some oxidation-prone amino acids showed low compatibility with this reaction. Chemoselective azidation of hydrazides followed by the addition of BME also succeeded in yielding the carboxylic acids via a thioester intermediate. This method is compatible with oxidation-prone amino acids. Different kinds of reaction sequences have been attempted for some specific examples. The same procedure, hydrazide activation by acetylacetone followed by BME addition [13], azidation followed by hydrolysis in basic aqueous conditions have been used [12, 24], but to the best of our knowledge, such a systematic and comprehensive evaluation has not been completed to date.

Chemoselective azidation of hydrazides and subsequent ammonolysis or a Staudinger reaction also succeeded in the late-stage amide synthesis although a C-terminal Cys must be protected. C-terminal Glu hampers the efficient amide synthesis probably due to the intramolecular anhydride formation followed by hydrolysis. This undesired reaction was suppressed by using a protocol other than a low pH aqueous buffer, to generate a peptide azide in TFA, but the versatility of the TFA condition was not so strong and side reactions involving Curtius rearrangement occurred more frequently. These results suggest that it is important to choose appropriate reaction conditions according to the components and sequence of peptides.

A general strategy to obtain both acid and amide peptides requires double SPPS using a resin with different linkers. In contrast, our protocols allow the performance of only a single SPPS to obtain both peptides. For example, the synthesis of modelin-5-COOH and -CONH2 using different linkers requires a total of 64 steps (16 couplings and 16 removals of Nα protection for each SPPS). In comparison, late-stage transformation reduces the number of synthetic steps to 34 (32 steps for peptide elongation and two steps for the transformation) and additionally produces a hydrazide as another component to enrich the library. This benefit was confirmed by evaluating the antimicrobial activity of the modelin-5 derivatives, leading to the unexpected discovery that modelin-5-CONHNH2 showed the most potent activity. Considering the antimicrobial peptide with C-terminal hydrazide, Li et al. [24] reported that the antimicrobial spectrum of Chex1-Arg20, an antimicrobial peptide, was broadened by incorporation of the hydrazide. They hypothesized that the broadened spectrum of activity may be due to the stability against bacterial enzyme attacks being improved in the hydrazide. Since modelin-5-CONH2 has a potent ability to kill Bacillus subtilis via membranolytic modes of action [25], the hydrazide might also improve the stability against bacterial enzymes. Efforts to exploit the mechanism and influence of C-terminal hydrazide modification into the antimicrobial activity are in progress in our laboratory.

Abbreviations

| Acm: |

acetamidomethyl |

| Ala: |

alanine |

| aq: |

aqueous solution |

| Arg: |

arginine |

| BME: |

β-mercaptoethanol |

| Boc: |

tert-butoxycarbonyl |

| CH3CN: |

acetonitrile |

| CuSO4∙5H2O: |

copper (II) sulfate, 5-hydrate |

| Cys: |

cysteine |

| DCM: |

dichloromethane |

| DIPCI: |

N,N’-diisopropylcarbodiimide |

| DMF: |

N,N-dimethylformamide |

| E. coli: |

Escherichia coli |

| Et2O: |

diethyl ether |

| Fmoc: |

9-fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl |

| Glu: |

glutamic acid |

| Gly: |

glycine |

| Gn: |

guanidine |

| HCl: |

hydrochloride |

| His: |

histidine |

| HPLC: |

high-performance liquid chromatography |

| IBX: |

2-iodoxybenzoic acid |

| Ile: |

isoleucine |

| LB: |

lysogeny broth |

| LCMS: |

liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry |

| Leu: |

leucine |

| Lys: |

lysine |

| MeOH: |

methanol |

| Met: |

methionine |

| NaNO2: |

sodium nitrite |

| NBS: |

N-bromosuccinimide |

| NH4OAc: |

ammonium acetate |

| Oxone: |

potassium peroxymonosulfate |

| OxymaPure: |

ethyl cyanohydroxyiminoacetate |

| Phe: |

phenylalanine |

| Pro: |

proline |

| rt: |

room temperature |

| Ser: |

serine |

| SPPS: |

solid-phase peptide synthesis |

| TCEP: |

tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine |

| TFA: |

trifluoroacetic acid |

| Thr: |

threonine |

| TIS: |

triisopropylsilane |

| Trp: |

tryptophan |

| Trt: |

trityl |

| Tyr: |

tyrosine |

| Val: |

valine |

Supplementary materials

The supplementary material for this article is available at: https://www.explorationpub.com/uploads/Article/file/100823_sup_1.pdf.

Declarations

Acknowledgments

ST is grateful for a scholarship from the Amano Institute of Technology.

Author contributions

ST: Investigation, Writing—original draft. MK: Investigation. YT: Methodology. TN and NM: Writing—review & editing, Supervision. KS: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI Grant number [JP22K05349] and Research Institute of Green Science and Technology Fund for Research Project Support [2023-RIGST-22201] National University Corporation Shizuoka University. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2023.