Affiliation:

1Postgraduate school of Internal Medicine, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Modena, Ospedale Civile di Baggiovara, 41126 Modena, Italy

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6217-2914

Affiliation:

1Postgraduate school of Internal Medicine, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Modena, Ospedale Civile di Baggiovara, 41126 Modena, Italy

Affiliation:

2Department of Internal Medicine, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Modena, Ospedale Civile di Baggiovara, 41126 Modena, Italy

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5644-2508

Affiliation:

2Department of Internal Medicine, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Modena, Ospedale Civile di Baggiovara, 41126 Modena, Italy

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9886-0698

Affiliation:

3Department of Dermatology, Head and Neck Skin Cancer Service, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Modena, Ospedale Civile di Baggiovara, 41126 Modena, Italy

Affiliation:

4Department of Internal Medicine and Chief of postgraduate school of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Modena, Ospedale Civile di Baggiovara, 41126 Modena, Italy

Email: pietro.andreone@unimore.it

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4794-9809

Explor Drug Sci. 2023;1:468–474 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/eds.2023.00031

Received: May 11, 2023 Accepted: October 24, 2023 Published: December 27, 2023

Academic Editor: Cheorl Ho Kim, Sungkyunkwan University, Samsung Advances Institute of Health Science and Technology (SAIHST), Republic of Korea

The article belongs to the special issue Innovative Therapeutics in Hepato-Gastroenterology

Reactivation of hepatitis B virus (HBV; RHBV) is a significant concern during immunosuppressive therapy, as it can lead to severe hepatitis and liver failure. The article reports a case of RHBV during treatment with guselkumab, an interleukin-23 inhibitor in a patient with inactive HBV infection and psoriasis. This report highlights the importance of screening for HBV prior to immunosuppressive therapy and initiating prophylactic therapy when necessary to prevent reactivation and its complications.

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a major global health concern, affecting an estimated 296 million people worldwide with 1.5 million new infections each year, and it can lead to chronic liver disease, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma [1]. As eradicative therapy is not yet available [2–4], after infection, the virus can persist in a latent or “inactive” state within liver cells, and many individuals with HBV infection remain asymptomatic and may not be aware of their status [1]. Reactivation of HBV (RHBV) is defined as a sudden and rapid increase in HBV-DNA level by at least 100-fold in those with previously detectable HBV-DNA or reappearance of HBV-DNA viremia in individuals who did not have viremia prior to the initiation of immune suppressive or biological modifier therapy or cancer chemotherapy [3–6]. RHBV can occur during periods of immunosuppression, such as during chemotherapy, or immunosuppressive therapies for autoimmune or inflammatory diseases and after organ transplantation. This reactivation can lead to significant complications, including severe hepatitis and liver failure [3, 5], and is therefore a significant concern for patients undergoing immunosuppressive therapy of any kind. In addition to the health burden of HBV, a significant financial burden is also associated with the disease and its complications, which may require hospitalization and/or intensive care treatment [1, 5–7].

This report was prompted by a recently published study regarding the use of interleukin-23 (IL-23) inhibitors in patients with inactive or chronic HBV or HCV infection and psoriasis [8]. In this instance, a patient with RHBV occurring during immunosuppressive therapy with guselkumab for psoriasis is discussed. This report is specifically focused on preventing and treating this potentially life-threatening complication.

Moderate-to-severe psoriasis (typically defined as involvement of more than 5 to 10 percent of the body surface area, or involvement of the face, palm, sole, or disease that is otherwise disabling) generally requires phototherapy or systemic therapies such as retinoids, methotrexate, cyclosporine, apremilast, or biologic immune modifying agents [9, 10]. Biologic agents as monotherapy or combined with other topical or systemic medications have robust efficacy and a high benefit-to-risk ratio and are currently recommended for the treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis in international guidelines [10–12]. Numerous factors and comorbidities influence the choice of treatment [13].

Biologic agents used in the treatment of psoriasis include the anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents, the anti-IL-12/IL-23 antibody ustekinumab; the anti-IL-17 antibodies secukinumab and ixekizumab; the anti-IL-17 receptor antibody brodalumab; and the anti-IL-23 antibodies guselkumab, tildrakizumab, and risankizumab [9].

The IL-23 inhibitors are a class of biologics that specifically inhibit the p19 subunit of IL-23, thereby also reducing the production of other pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-17 and IL-22 [9].

Guselkumab is an IL-23 inhibitor administered subcutaneously and is approved for the treatment of adult patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis in both the USA and the EU; it has a favourable safety profile and long-term tolerability, as well as evidence of efficacy in patients with prior failure of other biologics [14–19].

A 73-year-old lady with childhood-onset psoriasis was initially treated with high-dose steroids, methotrexate for over 20 years; phototherapy, photochemotherapy, and cycles of cyclosporine were all ultimately discontinued for inefficacy. Other comorbidities included obesity and a 40-g daily alcohol consumption.

In 2013, her psoriasis was deemed eligible for treatment with TNFα inhibitor and during screening, she was found to be hepatitis B core antibody (HBcAb)-positive and hepatitis B surface antibody (HBsAb)-positive (the latter with a titer of 11 UI/mL). Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and HBV viral load were undetectable. Liver tests and ultrasound scanning were normal. Access to information useful for determining the source or exact time of infection was not available. Additionally, no symptoms or laboratory findings compatible with acute hepatitis were detected.

From 2013 to 2019, the patient received anti-TNFα treatment (adalimumab) and many other biological therapies for psoriasis (ustekinumab, secukinumab, apremilast, and ixekizumab), all eventually discontinued for inefficacy.

During each of the above therapeutic regimens, HBV serology (HBsAg negative, HBcAb and HBsAb positive) remained reportedly unchanged. Liver tests were reportedly normal during all therapeutic regimens above as well, and no prophylactic therapy for HBV was ever undertaken. Lastly, in May 2019, she initiated guselkumab. During the first two years of guselkumab, liver tests remained normal.

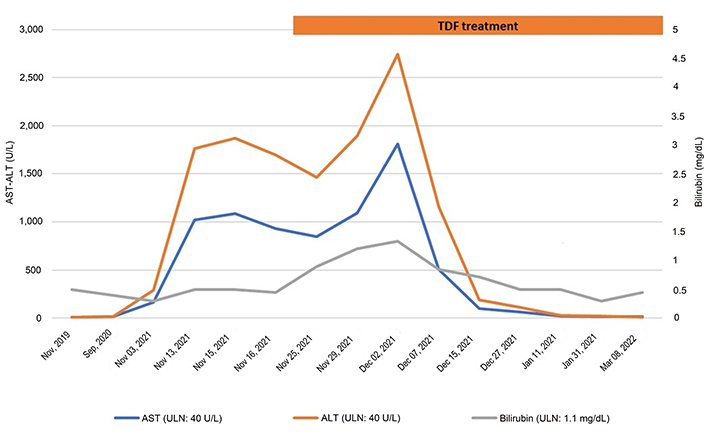

Guselkumab was administered on November 6, 2021 as scheduled, followed by the prescription of a ketogenic diet in the same month. Routine blood tests after two weeks showed raised transaminases (4–5 ULN), which worsened in the following 20 days, reaching > 20 ULN (Figure 1). For this reason, the patient was then referred by her physicians for hepatological care to our Outpatient Liver Clinic.

Liver biochemistry course before and during the antiviral treatment with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF). AST: aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase

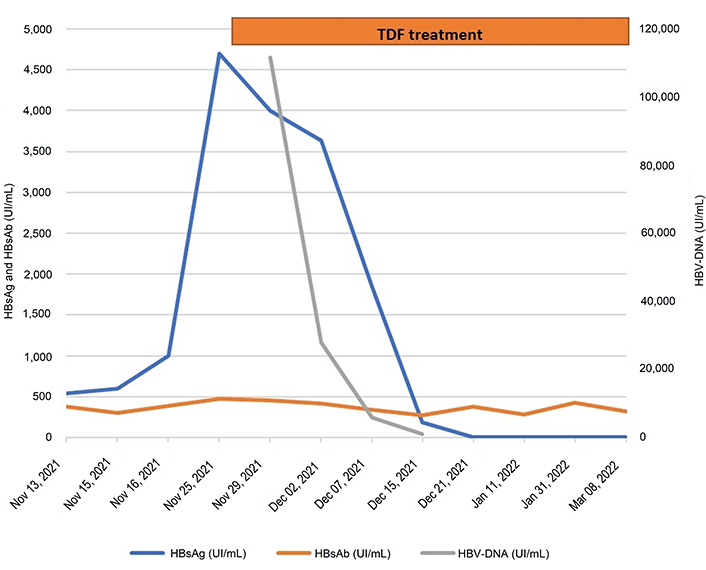

At the time of her first visit to our clinic (November 20, 2021), the patient was asymptomatic. Ultrasonography showed mild hepatomegaly and moderate steatosis. Virological tests (Figure 2) showed positive HBsAg (4,704 UI/mL), detectable HBV viral load (111.594 UI/mL), and positive HBsAb (472 UI/mL), suggestive of RHBV possibly associated with HBsAg escape mutation. Analysis of the surface gene did indeed reveal two escape mutations (P142L and G145R), not associated with drug resistance. HCV, HAV, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and autoimmune screening were negative and the patient had suspended all alcohol consumption a few months earlier.

HBV-DNA, HBsAg, and HBsAb course before and during the antiviral treatment with TDF

While waiting for the results of the hepatitis B surface gene test, treatment with TDF was pre-emptively initiated. A progressive reduction of transaminases and HBV viral load suppression was observed in the following weeks.

The patient remained persistently asymptomatic during the whole monitoring period. By the time the next scheduled administration of guselkumab was due (at the beginning of January 2022), liver enzymes and HBV serology were down to normal values and the patient was on tenofovir. Therefore, it was not deemed necessary to discontinue guselkumab administration, although the patient decided of her own will to delay her next administration until May 2022.

In short, we have reported on a case with latent HBV disease manifesting RHBV in the course of immunosuppressive therapy with guselkumab for psoriasis.

It is impossible to completely rule out that the ketogenic diet may have triggered an increase in liver enzymes. However, such a major elevation and complete normalization of liver tests after antiviral therapy strongly support the contention that RHBV was indeed the root cause of acute hepatitis in this patient.

Our bibliographic research (conducted using the keywords “guselkumab”, “psoriasis”, and “HBV” in PubMed from 2012 to 2023) found only two other case reports further to the study by Messina et al. [8]. This represents scarce evidence of reactivation of major hepatitis viruses during IL-23 inhibitor therapy, although few studies have been published so far on this relatively novel treatment strategy.

The first published report describes an HBsAg-negative 46-year-old man with HBsAb and HBcAb positivity who was successfully treated with guselkumab [20]. No evidence of RHBV was registered after 1 year of treatment despite the fact that he was not submitted to prophylaxis for RHBV. Conversely, in the report by Messina et al. [8], the patient had isolated HBcAb positivity but was treated with lamivudine to prevent RHBV infection.

The second published case study reports on a 13-year-old girl with chronic HBV infection (HBsAg-positive and HBV-DNA 3,400 IU/mL) treated with ustekinumab and guselkumab [21]. Also, this patient received entecavir prophylaxis to prevent RHBV.

All three of these previously published cases differ from the one reported in this instance, as the first was evaluated only one year after beginning therapy with guselkumab, while the remaining two were subjected to drug prophylaxis to prevent the risk of viral reactivation [8, 20, 21].

In conclusion, this case report suggests that when exposed to immune-suppressive treatment with guselkumab, individuals with a previous HBV infection should be routinely surveilled with liver enzyme and virological analyses aimed at early recognition and prompt treatment of RHBV.

HBcAb: hepatitis B core antibody

HBsAb: hepatitis B surface antibody

HBsAg: hepatitis B surface antigen

HBV: hepatitis B virus

IL-23: interleukin-23

RHBV: reactivation of hepatitis B virus

TDF: tenofovir disoproxil fumarate

TNF: tumor necrosis factor

EF and AACC: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. CC: Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing. AL: Writing—review & editing. CL: Writing—review & editing, Resources. PA: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This study (case report) has been waived by Ethics Committee of Università degli studi di Modena e Reggio Emilia according to their regulation about case reports (DGR del 19 giugno 2023, n. 1029 “Adozione del regolamento dei Comitati Etici Territoriali CET della Regione Emilia-Romagna, ai sensi dell’art. 3, comma 8, del D.M. 30 gennaio 2023”) in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from all participants.

Informed consent to publication was obtained from relevant participants.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2023.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2023. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 3769

Download: 28

Times Cited: 0

Davide Scalabrini ... Pietro Andreone

Matteo Biagi ... Pietro Andreone