Abstract

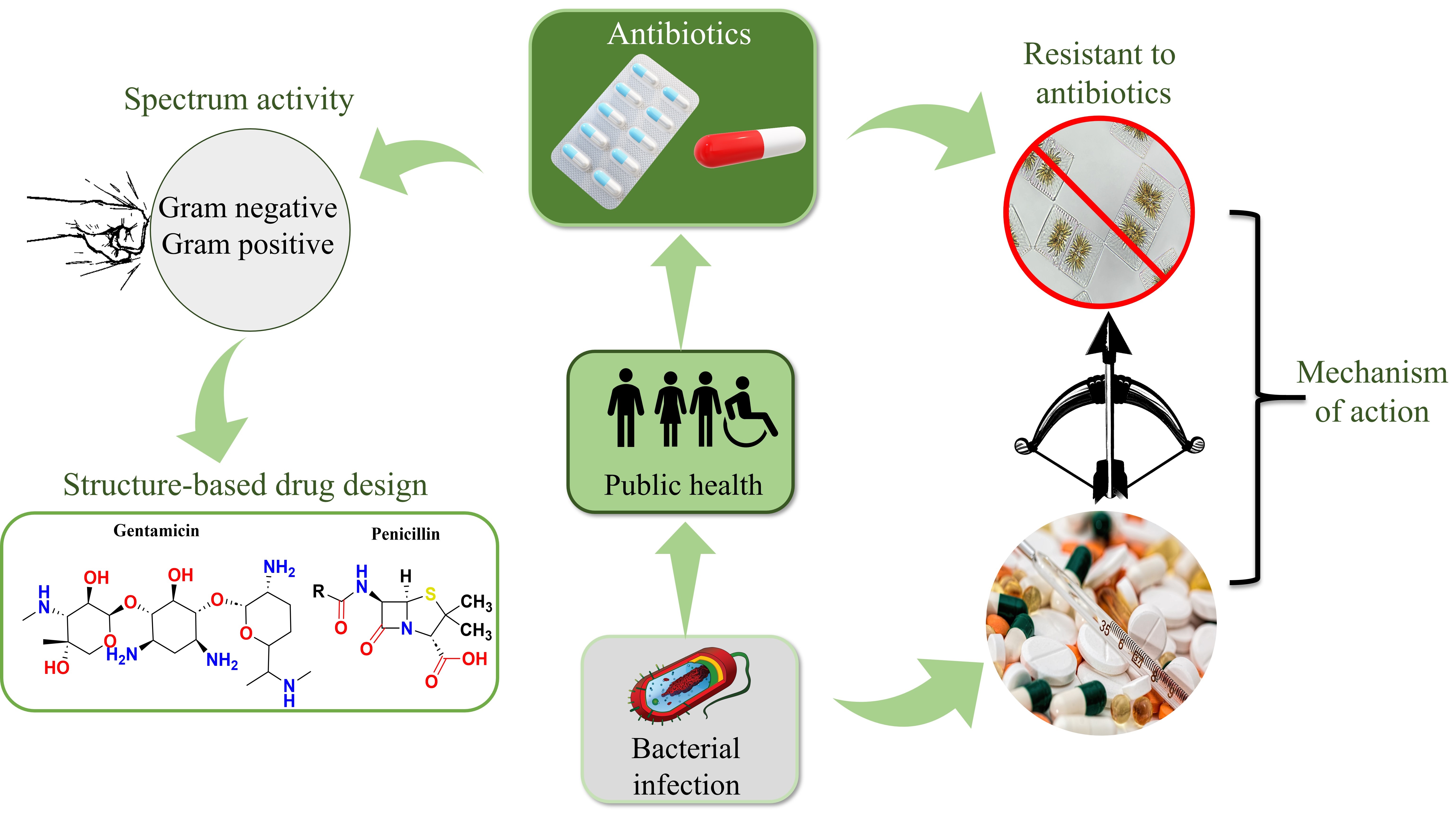

Antibiotic resistance is a significant threat to public health and drug development, driven largely by the overuse and misuse of antibiotics in medical and agricultural settings. As bacteria adapt to evade current drugs, managing bacterial infections has become increasingly challenging, leading to prolonged illnesses, higher healthcare costs, and increased mortality. This review explores the critical role of antibiotics in fighting infections and the mechanisms that enable bacteria to resist them. Key antibiotics discussed include carvacrol, dalbavancin, quinolones, fluoroquinolones, and zoliflodacin, each with unique actions against bacterial pathogens. Bacteria have evolved complex resistance strategies, such as enzyme production to neutralize drugs, modifying drug targets, and using efflux pumps to remove antibiotics, significantly reducing drug efficacy. Additionally, the review examines the challenges in antibiotic development, including a declining discovery rate of novel drugs due to high costs and regulatory complexities. Innovative approaches, such as structure-based drug design, combination therapies, and new delivery systems, are highlighted for their potential to create compounds with enhanced action against resistant strains. This review provides valuable insights for researchers and developers aiming to combat antibiotic resistance and advance the development of robust antibacterial therapies for future health security.

Keywords

Antimicrobial resistance, drug development, antibacterial therapies, resistance mechanismIntroduction

Antibacterial medications are essential for treating bacterial infections, significantly reducing mortality and morbidity [1]. However, the rising threat of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) poses a challenge to public health by complicating treatment, increasing healthcare costs, and limiting therapeutic options [2]. This review examines the critical role of antibacterial drugs in managing infections and the urgent challenges posed by AMR. Antibacterial drugs operate by targeting crucial bacterial functions, such as cell wall and protein synthesis, to either inhibit growth or destroy bacterial cells [3]. Major antibiotic classes including penicillins, tetracyclines, and fluoroquinolones are commonly employed against infections like salmonellosis and tuberculosis [4]. However, the effectiveness of these treatments is significantly hindered by bacterial resistance mechanisms, such as antibiotic modification and target alteration.

The misuse of antibiotics in healthcare and agriculture has accelerated the development and spread of drug-resistant pathogens [5]. For instance, research has identified that resistant strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Klebsiella pneumoniae are particularly prevalent in hospital settings [6]. Additionally, antibiotics exposure impacts the environmental microbial populations, potentially affecting ecosystem dynamics and effecting human health [7].

The World Health Organization (WHO) has called for urgent action to address the spread of antibiotic resistance [8]. Efforts such as antibiotic stewardship programs and biotechnological innovations are being pursued to address resistant strains like methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) [9]. The increasing prevalence of resistant strains, particularly in opportunistic pathogens like S. aureus, emphasizes the need for novel infection control approaches.

Antibiotic resistance, driven by misuse and bacterial adaptations, poses a latent pandemic threat by fostering multidrug-resistant infections and outpacing the development of new treatments [10–12]. In 2019, an estimated 1.27 million people died directly from AMR worldwide [13]. To address these challenges, researchers are exploring biotechnological innovations such as micro-/nano-bioplatforms, bacteriophage therapies, and CRISPR-based antimicrobials as promising alternatives to conventional antibiotics. Table 1 outlines key antimicrobial drugs and their respective target microbes, emphasizing the pressing need to address resistance mechanisms.

Antimicrobial drugs with their mechanism of action

| S. No. | Antimicrobial drugs | Use | Target microbe | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Antisense phosphorothioate oligonucleotide | Helps fluoroquinolone-resistant Escherichia coli regain antibiotic sensitivity by targeting acrB gene | Escherichia coli | [14] |

| 2 | Amikacin | Effective against bacterial infections | Mycobacterium and Pseudomonas aeruginosa | [15] |

| 3 | Vancomycin and linezolid | Used to treat complex skin and soft-tissue infections brought on by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) as well as nosocomial pneumonia | Staphylococcus aureus | [16] |

| 4 | Penicillin G procaine and pirlimycin | Used for treating mastitis in lactating cows | Mycoplasma spp. and Streptococcus agalactiae | [17] |

| 5 | Silica-based biomaterials loaded with ferulic acid | Used in bone tissue engineering to promote bone graft healing and stop bacterial infections | Staphylococcus aureus and E. coli | [18] |

| 6 | Non-canonical amino acids (NCAAs) | Plays a role in designing antimicrobial peptides to combat multidrug-resistant bacteria | Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria | [19] |

| 7 | Ciprofloxacin | This medication is a component of a new thermo-responsive hydrogel formulation intended for drug-eluting uses | Gram-negative bacteria | [20] |

| 8 | Taromycin A and Gassericin A | Exhibit binding mechanism by interacting with Lys 234 | Antibiotic resistant bacteria that produce TEM-1 β-lactamases | [21] |

Resistant bacteria use various mechanisms, including drug target modification, biofilm formation, and efflux pump activation, while the genetic transfer of resistance genes promotes their survival in antibiotic-rich environments [9, 22, 23]. The Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS) further highlights the increasing burden of diseases caused by resistant microorganisms worldwide [24].

This review highlights the essential role of antibacterial drugs in managing infections and the urgent challenge posed by AMR. It also explore emerging strategies, including nanotechnology and bacteriophage therapy, that show promise in targeting resistant strains effectively [25]. Additionally, this work also discusses antibiotic classifications, mechanisms, bacterial resistance strategies, and best practices for developing effective antibiotics.

History of antibiotic and emergence of resistance

Historically, antibiotics transformed infectious disease management, but bacteria quickly developed resistance. During the “Golden Age” of antibiotic discovery (1930s–1980s), key classes such as β-lactams and aminoglycosides were introduced, yet bacterial resistance soon followed [26]. The widespread application of antibiotics by humans has caused resistant bacteria to emerge, exacerbating the long-standing issue of antibiotic resistance [27]. Complicating treatment efforts is the discovery of novel resistance mechanisms brought about by the transition from focusing on planktonic bacteria to comprehending biofilm networks [28].

Key historical milestones:

1928—Penicillin’s discovery, which initiated the development of contemporary antibiotics [29].

1942—Emergence of bacterial resistance to penicillin [29].

1980 to present—A complete shift towards the production of semi-synthetic antibiotics but a decline in new classes [30].

The arms race between bacteria and antibiotics endures, as evidenced by ancient antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) even in pristine environments, indicating longstanding bacterial adaptation [31]. The use of antibiotics in agricultural contexts has resulted in the selection of resistant strains, which has complicated the resistance landscape [32].

Principle and classification of antibacterial drugs

Antimicrobial drugs work by focusing on particular bacterial functions, including DNA replication, protein synthesis, and cell wall construction. Their spectrum ranges from broad to narrow, and they may encounter bacterial resistance via efflux pumps or enzyme degradation. Drug efficacy and dosage are determined by pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, whereas pharmacogenomics customizes therapies according to genetic variables. Combination treatments reduce resistance and increase efficacy. To reduce adverse effects and fight resistance, antibiotic stewardship and appropriate therapeutic use including targeted and empirical therapy are essential [33]. Antibacterial agents are categorized into five main groups: sources, type of action, function, chemical structure, and spectrum of activity.

On the basis of sources

Natural

Antibacterial drugs can be derived from natural sources such as plants, animals, and microorganisms. Some of the examples of naturally occurring antibacterial agents and their mechanisms of action are shown in Table 2 [34].

Some of the examples of naturally occurring antibacterial agents and their mechanisms of action

| Naturally occurring antibacterial drugs | Mechanism of action | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Trans-cinnamaldehyde | Inhibits the growth of multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli by disrupting the cell wall integrity, leading to cell lysis and death. | [35] |

| Carvacrol | Damages bacterial cell membranes, prevents biofilm formation, and disrupts quorum sensing, making it effective against multidrug-resistant strains. | [36] |

| Gentisaldehyde | Alkylates essential cellular components such as DNA, RNA, and proteins, resulting in protein denaturation and alteration of nucleic acids, which interferes with bacterial function. | [37] |

| Phloroglucinaldehyde | Uses a dual mechanism by disrupting bacterial cell membranes and inhibiting essential metabolic pathways critical for bacterial survival. | [38] |

Semi‐synthetic antibacterials

Semi-synthetic antibacterials are chemically modified derivatives of natural antibiotics, aimed at enhancing efficacy and properties. Some of the semi-synthetic antibacterials with their mechanism of action are shown in Table 3 [34].

List of semi-synthetic antibacterial agents with their mechanisms of action

| Semi-synthetic antibacterials | Mechanism of action | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Ceftaroline | Binds to penicillin-binding proteins, disrupts cell wall synthesis and cross-linking, leading to weakened cell walls, bacterial lysis, and cell death. | [39] |

| Dalbavancin | Inhibits bacterial cell wall synthesis by binding to the D-alanyl-D-alanine terminus of peptidoglycan chains, disrupting transpeptidation, which results in a weakened cell wall and bacterial lysis. | [40] |

| Oritavancin | Utilizes three mechanisms: i) inhibition of transglycosylation, ii) inhibition of transpeptidation, and iii) disruption of bacterial cell membrane. | [41] |

Synthetic antibacterials

Synthetic antibacterials are artificially created compounds designed to inhibit or kill bacteria. Table 4 gives some of the examples of synthetic antibacterials with their mechanism of action [34].

List of synthetic antibacterial agents with their mechanisms of action

| Synthetic antibacterials | Mechanism of action | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Cresomycin | Binds strongly to its ribosomal target, blocking protein synthesis more effectively than other antibiotics. | [42] |

| Iboxamycin (IBX) | Targets bacterial ribosomes, disrupting protein synthesis in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, making it effective for multidrug-resistant infections. | [43] |

| Oxepanoprolinamide | Interferes with ribosomal function sites to halt bacterial growth and proliferation, effectively stopping protein synthesis and leading to cell death. | [44] |

Type of action

Bacteriostatic

The term “bacteriostatic” refers to substances that impede or prevent the growth of bacteria. Bacteriostatic antibacterials function by inhibiting the growth and replication of bacteria through various mechanisms. For example, sulphonamides act by blocking the early stages of folate synthesis, which is essential for bacterial DNA replication and cell growth [45]. Additionally, amphenicols prevent bacterial cells from the protein synthesis. They accomplish this function by attaching themselves to the bacterial ribosome’s 50S subunit and blocking the creation of peptide bonds during the translation process. In the end, this prevents bacterial growth and replication by interfering with the creation of vital proteins [46]. Furthermore, spectinomycin binds to the 30S ribosomal subunit, disrupting protein synthesis, and thereby hindering bacterial growth [47]. Lastly, trimethoprim interferes with the tetrahydrofolate synthesis pathway, which is crucial for DNA and protein synthesis in bacteria [48]. Each of these agents uses a distinct mechanism to prevent bacterial proliferation without directly killing the organisms.

Bactericidal

Bactericidal agents work by destroying bacterial cell walls or membranes, leading to bacterial death. Examples include penicillin and quinolones, such as levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin. For instance, carbapenems interfere with bacterial cell wall formation, leading to cell lysis and death [49]. Gentamicin blocks protein production, which is essential for bacterial survival [50]. Quinolones and fluoroquinolones inhibit bacterial DNA replication, preventing the cell from reproducing and leading to bacterial death [51]. Lastly, vancomycin disrupts cell wall construction, which weakens the bacterial cell structure and ultimately causes cell death [52]. Each of these agents targets a specific bacterial function, effectively eliminating the organisms.

Chemical structure

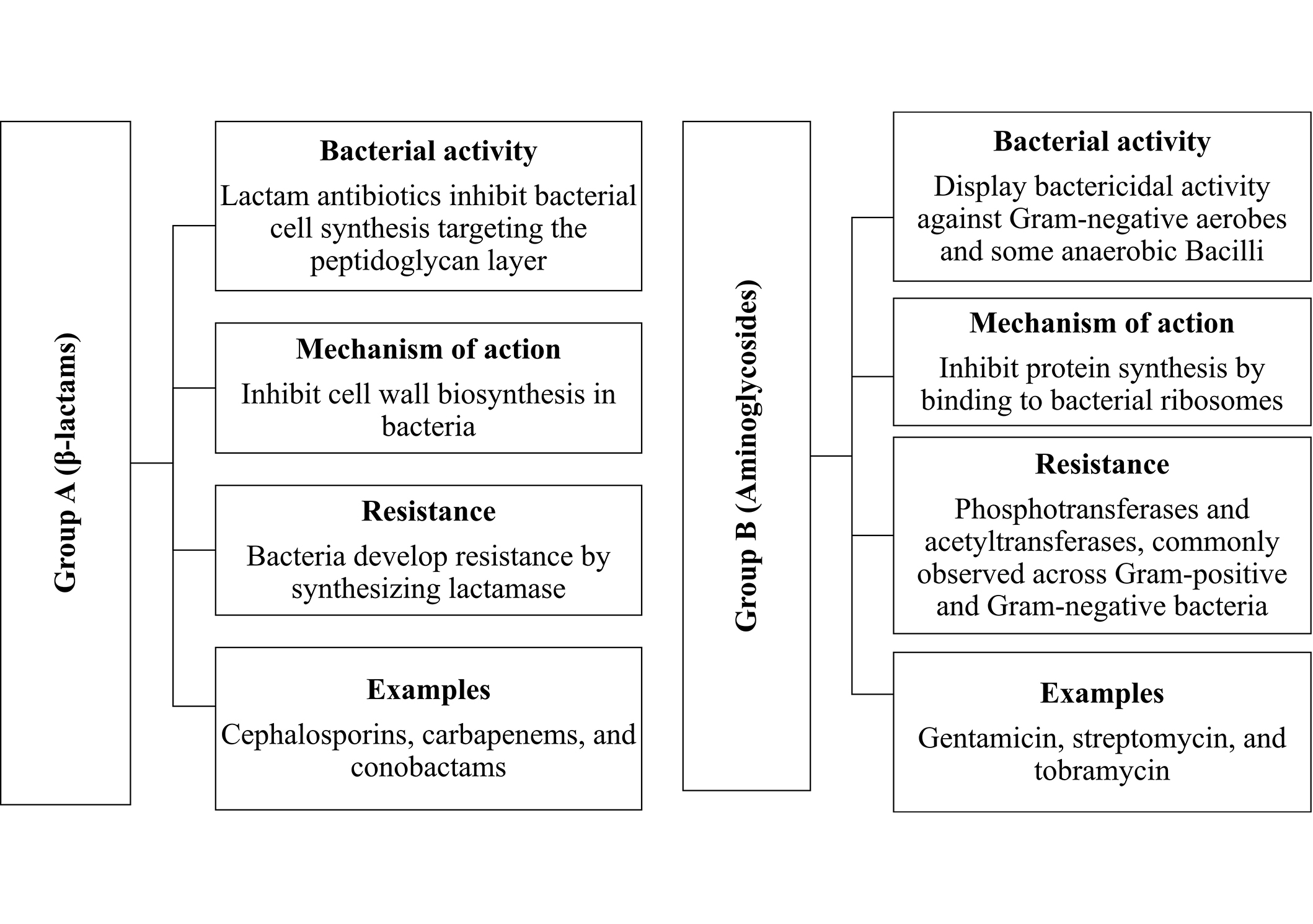

Group A (β‐lactams)

This category includes β-lactam antibiotics such as penicillin derivatives, cephalosporins, monobactams, and carbapenems. Figure 1 gives bacterial activity, mechanism of action, and resistance group A (β‐lactams) [53].

Presents bacterial activity, mechanism of action, and resistance for group A (β-lactams) and group B (Aminoglycosides)

Group B (Aminoglycosides)

Aminoglycosides, including streptomycin, gentamicin, sisomicin, netilmicin, and kanamycin, work by binding to bacterial ribosomes, disrupting protein synthesis, and inhibiting bacterial growth. Figure 1 gives bacterial activity, mechanism of action, and resistance group B (Aminoglycosides) [54].

Macrolides

A macrocyclic lactone ring with changeable side chains is a characteristic of macrolides by attaching themselves to the bacterial 50S ribosomal subunit, they prevent the production of proteins [55, 56]. Erythromycin, azithromycin, and clarithromycin are notable macrolides that are efficient against intracellular infections and have broad-spectrum action [57].

Tetracyclines

Tetracyclines are distinguished by their four rings by attaching to the 30S ribosomal subunit and blocking the attachment of aminoacyl-tRNA, they inhibit the production of proteins [58]. Tetracyclines perform well against a variety of atypical infections including Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [59].

Quinolones

Quinolones have a bicyclic ring structure that is frequently fluorine-modified [60]. They interfere with DNA replication by targeting bacterial gyrase and topoisomerase IV [61]. Because of their broad-spectrum activity and good tissue penetration, fluoroquinolones such as ciprofloxacin and moxifloxacin are used extensively [62, 63].

Sulfonamides

Consists of an aromatic amine with a sulfonamide group attached. It inhibits dihydropteroate synthase, preventing the production of folate, which is necessary for bacterial development. Commonly used sulfonamides in clinical settings include sulfadiazine and sulfamethoxazole [64].

Glycopeptides

Vancomycin and teicoplanin are well-known glycopeptide antibiotics (GPAs) used as last-resort treatments for severe infections [65]. They are distinguished by a heptapeptide backbone with numerous modifications, such as glycosylation and chlorination [66]. They bind to lipid II, disrupting the synthesis of bacterial cell walls, and are especially effective against resistant strains [67].

Functions

Antibiotics target essential bacterial processes such as cell wall synthesis, membrane function, protein synthesis, and nucleic acid synthesis. They can be categorized into four groups based on their mode of action: cell wall synthesis inhibitors, membrane function inhibitors, protein synthesis inhibitors, and nucleic acid synthesis inhibitors. Understanding these functions is crucial for determining how each antibacterial works. Each of these groups will be discussed briefly in the following sections [68].

Cell wall synthesis inhibitors

The bacterial cell wall, primarily composed of peptidoglycan, is crucial for structural integrity, making its synthesis a key target for antibiotics known as cell wall synthesis inhibitors. β-Lactam drugs, such as penicillin and cephalosporins, inhibit peptidoglycan synthesis by binding to penicillin-binding proteins, leading to bacterial lysis. Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria exhibit varying susceptibility to these drugs due to differences in their cell wall structures and the presence of β-lactamases that confer resistance [69].

Inhibitors of membrane function

Polymyxins are cyclic peptide antibacterial agents that selectively target the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria by disrupting their membrane structure and increasing permeability, leading to cell death. They are effective against Gram-negative bacteria due to their affinity for lipopolysaccharides, but have little to no effect on Gram-positive bacteria due to their thick cell walls. Therapeutically, polymyxins B and E are commonly used in chemotherapy [70].

Protein synthesis inhibitors

Protein synthesis inhibitors are antibiotics that target bacterial protein synthesis to treat infections, taking advantage of the slower protein synthesis in human cells to minimize side effects. These inhibitors disrupt various stages of protein synthesis, including initiation, elongation, and termination. While toxicity and resistance are concerns, the selective targeting of bacterial processes makes these drugs effective [71].

Inhibition of nucleic acid synthesis

Nucleic acid synthesis inhibitors are antibiotics targeting bacterial DNA and RNA synthesis, leveraging differences in prokaryotic and eukaryotic enzymes for selective toxicity. RNA inhibitors, like rifampin, block transcription by binding to RNA polymerase, while DNA inhibitors, such as quinolones, inhibit DNA gyrase, disrupting DNA replication. Other drugs, like nitrofurantoin and metronidazole, target anaerobic bacteria by damaging DNA strands. This disruption of nucleic acid synthesis ultimately leads to bacterial cell death [72].

Spectrum activity

Narrow spectrum antibacterials

Narrow spectrum antibacterials have a limited range of action, targeting either Gram-positive or Gram-negative bacteria specifically. These agents typically face less bacterial resistance. Table 5 provides the list of narrow spectrum antibacterials includes, methicillin, nafcillin, oxacillin, temocillin, and cloxacillin (dicloxacillin, flucloxacillin) [73].

Examples of narrow spectrum antibacterials with their binding site function

| Narrow spectrum antibacterial | Binding site function | References |

|---|---|---|

| Methicillin | Competitively blocking the transpeptidase enzyme, which is a type of penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs). | [74] |

| Nafcillin | Specifically targets PBPs essential for cell wall synthesis, aiding in cross-linking peptidoglycan for wall rigidity. | [75] |

| Oxacillin | The binding site is shaped by loops near helix 5, affecting substrate affinity; variants like OXA-2 and OXA-51 bind better to carbapenems. | [76] |

| Cloxacillin | Binds to serum albumin through hydrophobic interactions, with a 1:1 stoichiometry, as indicated by fluorescence spectroscopy studies. | [77] |

Broad spectrum antibacterial

Broad spectrum antibacterials target a wide range of pathogenic bacteria, including both Gram-positive and Gram-negative strains. Table 6 lists broad spectrum antibacterials include ampicillin, quinolones such as maxaquin (lomefloxacin), floxin (ofloxacin), noroxin (norfloxacin), tequin (gatifloxacin), cipro (ciprofloxacin), avelox (moxifloxacin), levaquin (levofloxacin), factive (gemifloxacin), and carbapenems [78].

Broad spectrum antibacterials with their binding site function

| Broad spectrum antibacterial | Binding site function | References |

|---|---|---|

| Quinolones | Inhibit DNA replication by binding to DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV. | [43] |

| Carbapenems | Inhibit cell wall synthesis by binding to penicillin-binding proteins. | [49] |

Antibacterial resistance

AMR refers to the ability of bacteria to survive and proliferate even in the presence of antibiotics, posing a significant threat to global public health [79, 80]. Bacteria can develop resistance through either intrinsic mechanisms (naturally possessed traits) or acquired mechanisms (through transformation, transduction, or conjugation of mobile genetic elements like transposons and plasmids). There are two main types of antibacterial resistance: natural antibacterial resistance, also known as intrinsic resistance, occurs naturally within a bacterial species without the involvement of horizontal gene transfer. In this case, bacteria inherently possess resistance traits, and they may express their resistance genes only when exposed to antibiotics. On the other hand, acquired antibacterial resistance develops when bacteria obtain resistance traits through horizontal gene transfer, acquiring genetic material from other bacteria. This form of resistance can also arise from mutations in the cell’s DNA during replication, which may enhance bacterial survival against antibiotic treatments [81–83].

Mechanism of antibacterial resistance

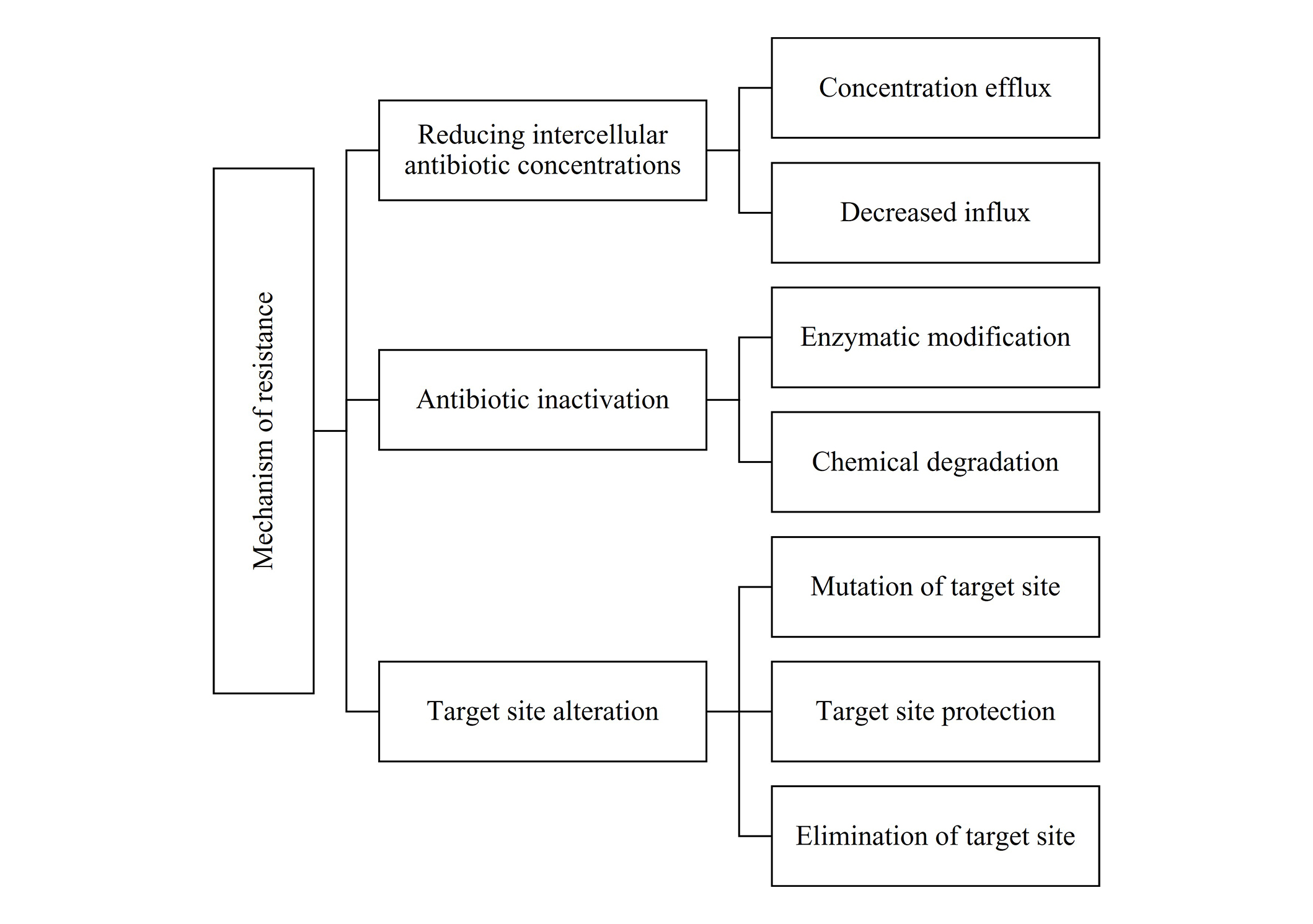

AMR complicates infection treatment through mechanisms such as reduced intracellular antibiotic concentration, antibiotic inactivation, and target site alteration. Efflux pumps and decreased cell permeability limit antibiotic entry, while enzymatic degradation (e.g., β-lactamases) and chemical modifications (phosphorylation, adenylation, acetylation) inactivate antibiotics. Target site mutations and modifications further reduce antibiotic binding, as seen with resistance to tetracyclines and macrolides. Combating antibacterial resistance requires a multimodal approach involving stringent antibiotic stewardship, combination therapies, and novel drug development (Figure 2) [79].

Spread of antimicrobial resistance

The spread of AMR can be attributed to several key factors: human practices, such as the overuse and misuse of antimicrobials, poor infection control, and limited public awareness; animal-related practices, including the extensive use of antibiotics in livestock and aquaculture, leading to transmission through food chains and direct contact; environmental factors, such as the release of antibiotics and resistant bacteria into water sources; and wildlife-related factors, with transmission occurring through contact with wildlife and increased habitat encroachment [84].

Discovery and development of novel drugs

Recent advancements in the discovery and development of novel therapeutics such as phage therapy, antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), CRISPR-Cas9, combination therapies, repurposing existing drugs, and in silico drug design have shown significant promise across various medical fields are explained below.

Phage therapy

Phage therapy offers a promising alternative to antibiotics, particularly against antimicrobial-resistant bacteria. It targets pathogenic bacteria with high specificity, preserving beneficial microbiota. Success stories and the establishment of phage banks and dedicated centers are enhancing personalized treatments and outcomes [85].

Antimicrobial peptides

AMPs are a promising class of agents with broad spectrum activity against antibiotic-resistant infections. Recent research focuses on optimizing AMPs for better stability and efficacy, with successful clinical trials treating skin infections and resistant strains. AMPs show potential as alternatives to conventional antibiotics [86].

CRISPR-Cas9

The CRISPR-Cas9 system enables precise targeting of antibiotic resistance genes in bacteria. Phage-mediated delivery allows effective gene editing, sensitizing bacteria to treatment. This technology shows promise for both therapy and advancing microbial genetics [87].

Combination therapies

Combination therapies that integrate antibiotics with phage therapy or AMPs enhance treatment outcomes against resistant infections by improving efficacy and reducing dosages. Research indicates that these combinations can successfully treat chronic infections, yielding higher success rates than single therapies. This synergistic approach underscores the importance of developing comprehensive strategies to optimize patient care [88].

Repurposing existing drugs

Repurposing existing drugs, such as anticancer drugs like imatinib and statins, shows promise in combating antibiotic-resistant bacteria. This approach utilizes existing safety data, speeding up the development of new treatments. Ongoing research into drug mechanisms aids in identifying potential repurposing candidates [89].

In silico drug design

In silico drug design uses computational tools and machine learning to accelerate the discovery of new antibacterial agents. Recent AI advancements improve the prediction of antimicrobial activity and the identification of potential drug candidates. Integrating in silico methods with traditional approaches enhances the efficiency of developing treatments for multidrug-resistant pathogens [90].

In oncology, anticancer peptides (ACPs) show promising potential for breast cancer therapy. Notably, lactoferricin B (LfcinB) and its derivatives exhibit cytotoxic effects against various breast cancer cell lines. Enhancing palindromic peptides, such as RWQWRWQWR, improves cancer cell selectivity and inhibits cell migration, thereby progressing the preclinical phase of drug discovery [91]. Additionally, the integration of non-canonical amino acids (NCAAs) into peptide designs has drawn significant interest in medicinal chemistry, enhancing hydrophobicity and bioactivity, especially for antimicrobial peptides targeting multi-drug-resistant bacteria. Systematic exploration of modified peptides through cheminformatics enables the creation of compounds with improved stability and efficacy for therapeutic use [19]. In cardiovascular therapy, atherosclerosis treatment, ground-breaking treatments are emerging. Inclisiran, a pioneering small interfering RNA (siRNA) drug, reduces low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol by inhibiting PCSK9, providing a viable option for patients unresponsive to statins. Furthermore, histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, including TMP195, RGFP966, and MC1569, target key pathways in inflammation and lipid metabolism, addressing the underlying causes of vascular aging and atherosclerosis [92]. These innovative approaches underline the potential of multi-target therapies in tackling complex diseases.

The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the repurposing of FDA-approved drugs for potential effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2. Key candidates include dexamethasone, hydroxychloroquine, remdesivir, and favipiravir. Originally developed for Ebola, remdesivir inhibits viral RNA polymerase, blocking replication, while favipiravir, initially approved for influenza, also prevents viral RNA production. Hydroxychloroquine has been investigated for its ability to block viral entry and modulate immune responses, and dexamethasone has shown mortality reduction in severe COVID-19 cases by dampening hyper-inflammatory reactions [93].

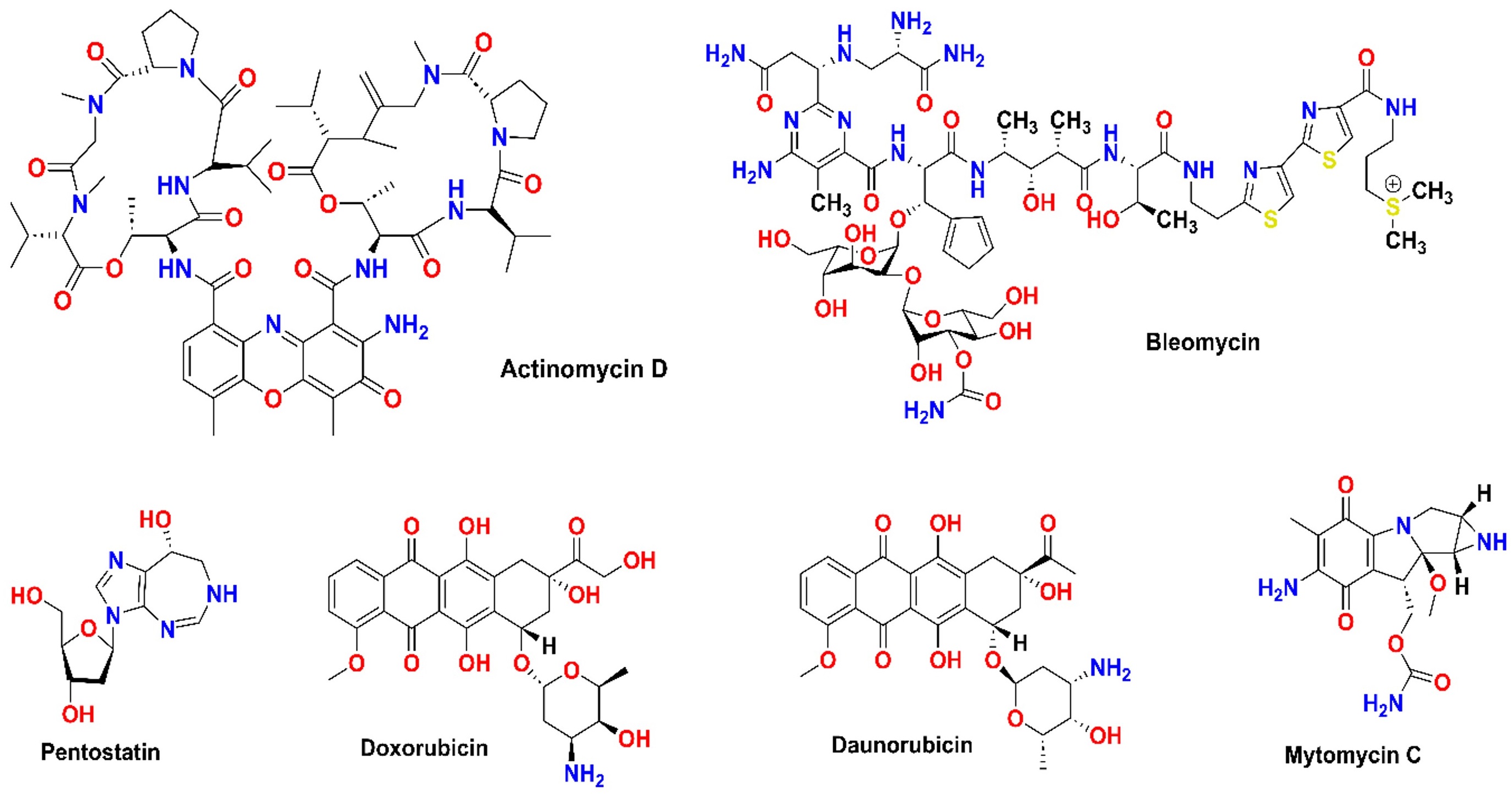

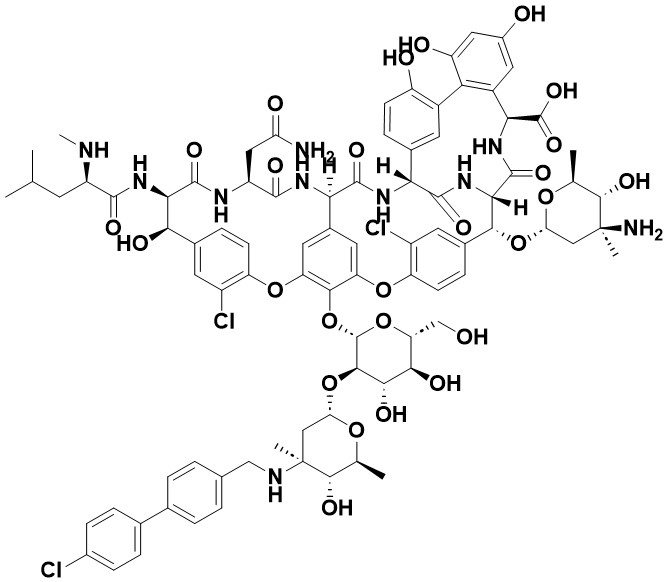

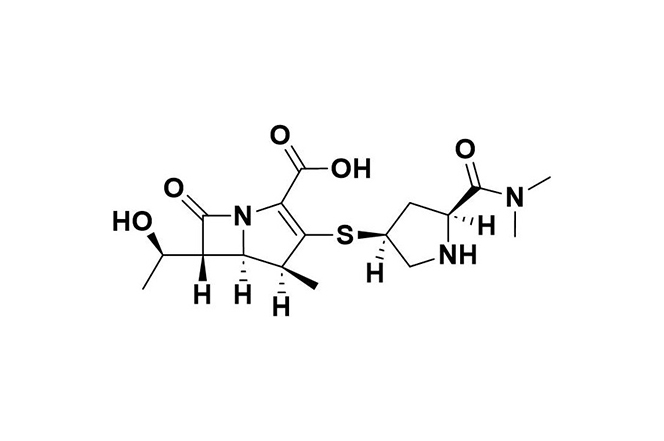

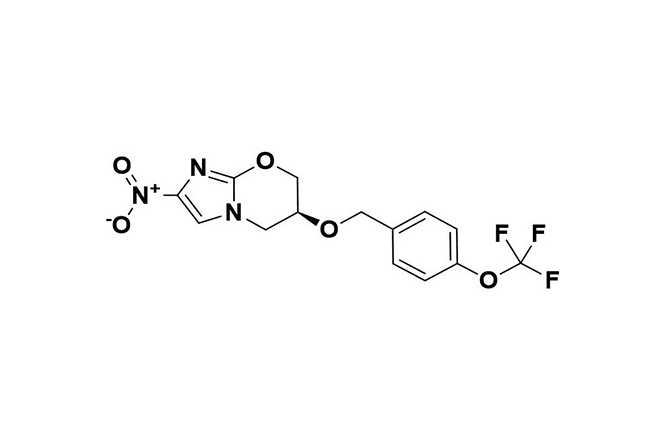

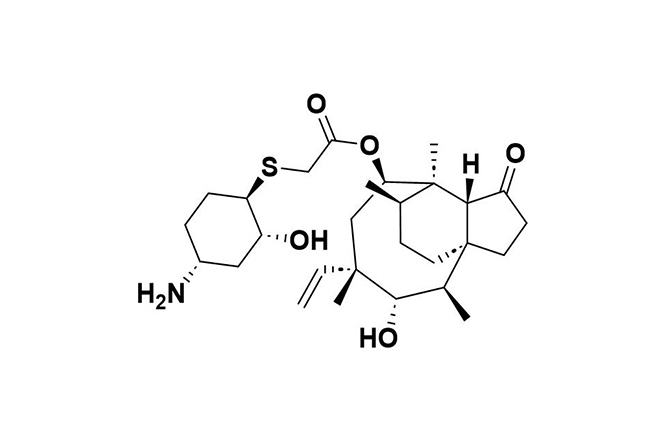

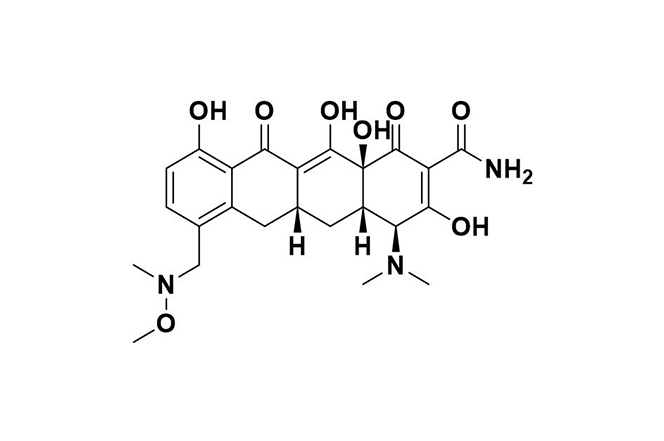

Natural products are also being re-evaluated for therapeutic use. Curcumin, despite its low availability, continues to gain attention for anticancer therapy, spurring research on improved formulations. Microbial metabolites have also emerged as promising candidates in cancer therapy, with compounds like bortezomib demonstrating efficacy by targeting proteasomal pathways Figure 3 [94]. These developments highlight the importance of exploring multiple pathways in drug discovery. Some of the examples of antibacterial drugs along with their mechanism of action are mentioned in Table 7. This table highlights the ongoing challenges in combating bacterial resistance, emphasizing the need for continuous innovation in antibiotic development.

Structure of microbial metabolites that are clinically used for cancer chemotherapy

The search for natural compounds to treat age-related diseases increasingly focuses on senolytics like dasatinib and quercetin. Originally developed for leukemia, dasatinib effectively targets and eliminates senescent cells, while quercetin, a flavonoid, promotes autophagy and reduces the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). Additionally, resveratrol and fisetin support healthy aging by activating sirtuins, enhancing autophagy, and selectively removing senescent cells. Compounds like cyclo-trijuglone, derived from traditional herbs, highlight the potential of blending traditional knowledge with modern pharmacology to develop new age-related therapeutics [95]. The synergy of natural compounds and advanced pharmacological strategies holds promise for tackling both age-related diseases and bacterial resistance.

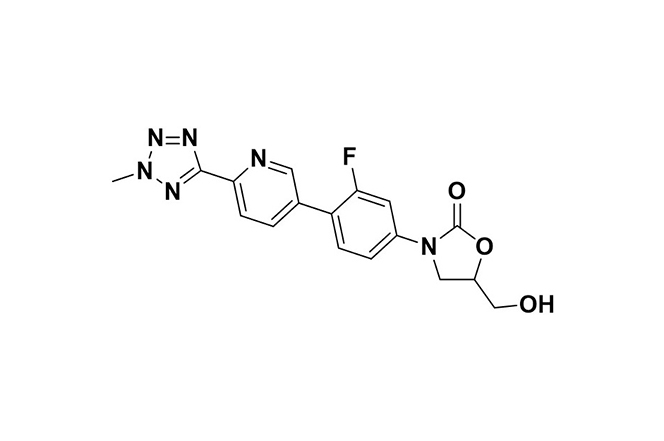

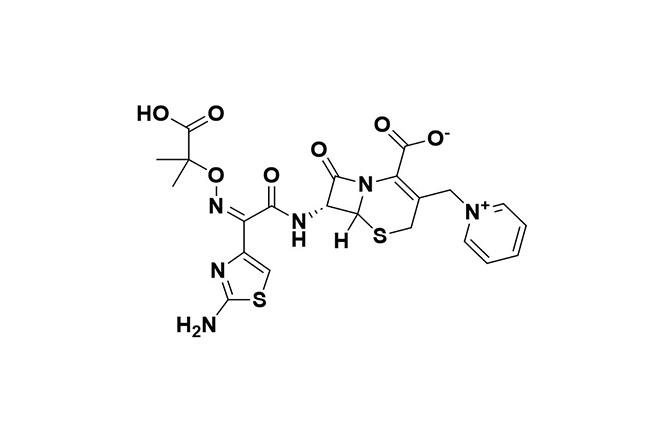

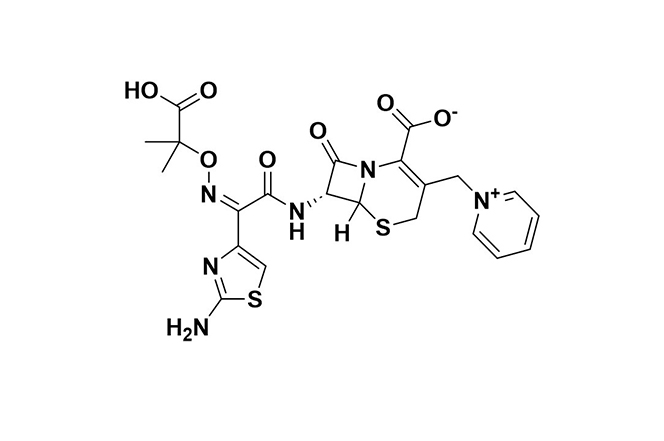

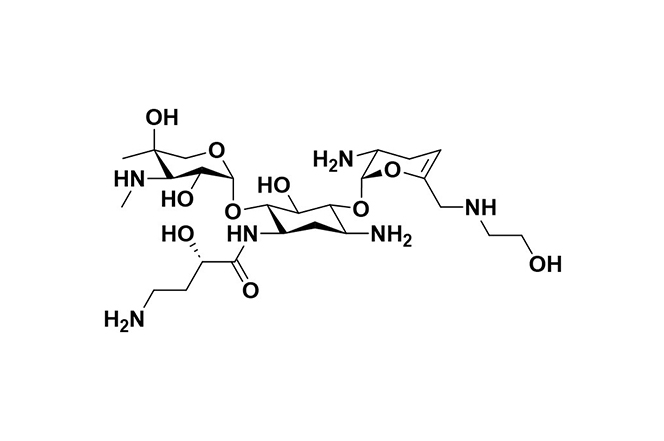

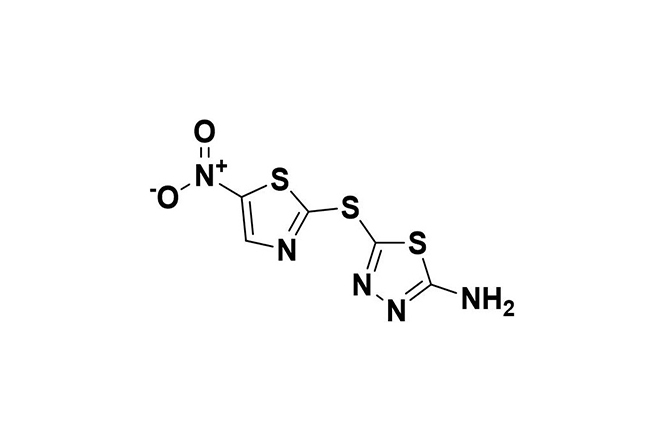

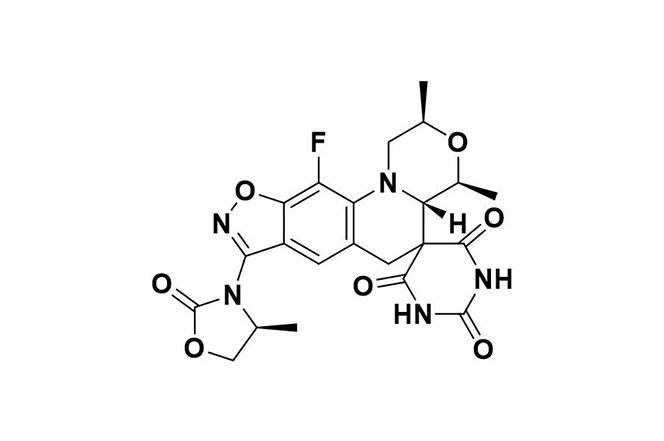

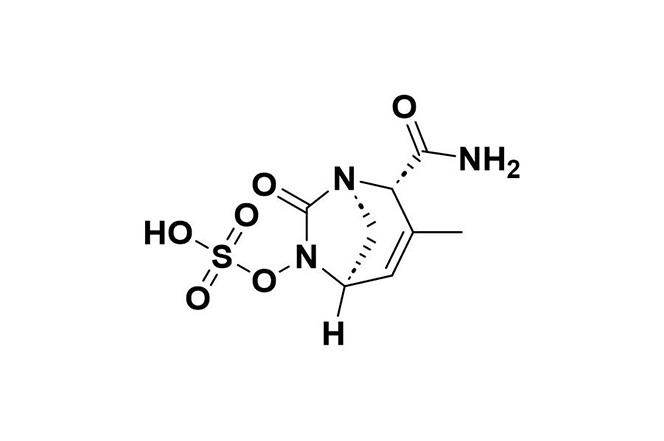

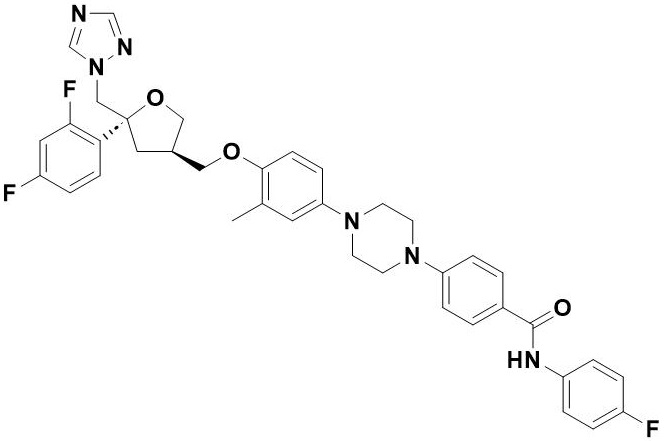

List of antibacterial drugs

| S. No. | Structure | Drug | Mechanism of action | Mechanism of resistance | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  | Tedizolid | Binds to 23S rRNA in the 50S ribosomal subunit, blocking protein synthesis initiation and aminoacyl-tRNA binding in bacteria. | Resistance arises through 23S rRNA mutations or cfr gene transfer, reducing the drug’s ribosomal binding affinity. | [96] |

| 2 |  | Ceftolozane-tazobactam | Combines bactericidal effects of ceftolozane with tazobactam’s β-lactamase inhibition. | Resistance involves metallo-β-lactamases and AmpC hyperproduction, reducing drug efficacy. | [97] |

| 3 |  | Oritavancin | Inhibits peptidoglycan synthesis by binding to D-Ala-D-Ala and D-Ala-D-Lac, blocking transglycosylation and transpeptidation. | Resistance due to changes in VanB operon expression or D-Lac precursor presence, which reduce drug sensitivity. | [98] |

| 4 |  | Ceftazidime-Avibactam | Ceftazidime disrupts cell wall synthesis via penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs); avibactam inhibits ceftazidime breakdown by β-lactamases. | Resistance stems from metallo-β-lactamases, specific class D enzymes, mutations in β-lactamase enzymes (e.g., KPC-3), along with reduced permeability and efflux. | [99] |

| 5 |  | Meropenem | Inhibits cell wall synthesis by binding to PBPs; vaborbactam enhances efficacy by inhibiting class A β-lactamases. | Resistance mechanisms include class B and D carbapenemases, altered PBPs, and increased efflux pump activity. | [100] |

| 6 |  | Pretomanid | In anaerobic conditions, generates reactive intermediates that inhibit respiration in non-replicating bacteria and disrupt protein and lipid synthesis in replicating bacteria. | Resistance primarily occurs through mutations in activation-related genes (e.g., Ddn, Fgd, fbiA/B/C), sometimes affecting CofC or rplC and conferring dual resistance with linezolid. | [101] |

| 7 |  | Lefamulin | Binds to the 50S ribosomal subunit, inhibiting peptide bond formation and protein synthesis in bacteria. | Resistance arises from genes like vga(A), cfr, and mutations in 23S rRNA and ribosomal proteins (rplC, rplD). | [102] |

| 8 |  | Sarecycline | Binds to the bacterial ribosome’s A site, blocking mRNA translation; also reduces inflammation by suppressing cytokines and neutrophil activation. | Resistance occurs through degradation, rRNA mutations, ribosomal protection (e.g., TetM, TetO), and efflux pumps like TetA. | [103] |

| 9 |  | Plazomicin | Inhibits protein synthesis by binding to the A-site of 16S rRNA in the 30S ribosomal subunit in Gram-negative bacteria. | Resistance is mostly due to aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes (AMEs), target site alterations, and changes in porin or efflux pump expression. | [104] |

| 10 |  | Halicin | Exhibits broad-spectrum antibacterial action by damaging DNA and disrupting the proton motive force (PMF), impeding bacterial adaptation and resistance. | Resistance is rare and mainly involves mutations affecting protein synthesis, transport, and nitroreduction. | [105] |

| 11 |  | Zoliflodacin | Inhibits bacterial type 2 topoisomerase, primarily targeting DNA gyrase, preventing fluoroquinolone cross-resistance and double-strand DNA breaks. | Resistance is uncommon, associated with gyrB gene alterations, and presents minimal cross-resistance with other antibiotics. | [106] |

| 12 |  | Durlobactam | Restores Acinetobacter baumannii’s susceptibility to sulbactam by inhibiting class D carbapenemases, β-lactamases, and reducing PBP2. | Resistance may occur through metallo-β-lactamases, certain PBP mutations, and the AdeIJK efflux system. | [107] |

| 13 |  | Opelconazole | Inhibits 14-α-demethylase (CYP51A), blocking ergosterol formation in fungal cell membranes, effective against Aspergillus and Mucorales. | Resistance primarily arises from ERG11 gene mutations, notably TR34/L98H in cyp51A, which reduce drug binding efficacy. | [108] |

Conclusions

This review has highlighted the critical importance of antibacterial drugs in combating infections and the growing threat posed by AMR. It covers the history and evolution of antibiotics, tracing their journey from the discovery of penicillin to the current era of semi-synthetic and synthetic antibacterials. The classification of antibacterial drugs is discussed based on their sources, mechanisms of action, chemical structures, and spectrum of activity. The mechanisms of antibacterial resistance, including intrinsic and acquired strategies employed by bacteria, are examined alongside factors contributing to the spread of resistance, such as the overuse of antibiotics in healthcare and agriculture. The review also highlights recent advances in drug discovery and development, including innovative approaches such as the use of NCAAs, repurposing existing drugs, and exploring natural products. Additionally, examples of new antibacterial agents are presented, along with insights into their mechanisms of action and emerging resistance patterns.

The increasing prevalence of resistant bacterial strains underscores the urgent need for continued innovation in antibiotic development. Multi-faceted approaches combining traditional and cutting-edge strategies show promise for addressing this global health threat. Key priorities include developing robust models to evaluate new antimicrobial agents and exploring combination therapies to combat resistance. Further, improving antibiotic stewardship in healthcare and agriculture and investigating alternative therapeutic approaches like bacteriophage therapy. Hence, by pursuing these priorities through collaborative, cross-disciplinary efforts, the scientific and medical communities can work to stay ahead of evolving bacterial resistance and ensure effective treatments remain available for future generations. Continued research, innovation, and responsible antibiotic use will be critical in preserving the efficacy of these life-saving drugs.

Abbreviations

| AMPs: | antimicrobial peptides |

| AMR: | antimicrobial resistance |

| NCAAs: | non-canonical amino acids |

Declarations

Author contributions

AMR and SSP: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. KD and RD: Validation, Writing—review & editing, Supervision. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

Publisher’s note

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.