Abstract

Obesity is a multifactorial disease linked to many comorbidities and has an impact on brain health. It is also known that obesity disrupts the endocannabinoid (eCB) system in the central nervous system and in the periphery, which complicates the underlying mechanisms behind obesity. However, weight loss through lifestyle interventions or bariatric surgery may alleviate obesity-related comorbidities, as well as restore eCB tone. Several studies have reported a decrease in circulating eCBs following weight loss, likely due to the positive association of these mediators with fat mass. However, further research is needed to clarify whether this reduction is a consequence of weight loss or plays a role in facilitating it. This review explores changes in circulating eCBs following weight loss and their potential roles in cerebral homeostasis and the reward system. It examines how lifestyle modifications and bariatric surgery may influence central eCB signalling and contribute to long-term weight loss success. Understanding the mechanisms behind improved brain function after weight loss could provide insights into optimizing obesity treatments.

Keywords

Endocannabinoids, obesity, bariatric surgery, lifestyle interventions, brainIntroduction

Beyond the accumulation of body fat, obesity is a complex chronic disease in which abnormal adiposity impairs health and increases the risk of long-term medical complications [1, 2]. In addition, the crosstalk between excess body weight and neurobiological and psychiatric disorders was documented several times [3, 4]. Individuals with severe obesity have higher risks of developing Alzheimer’s disease [5], as well as experiencing major episodes of depression in their lifetime [6]. Therefore, it has become increasingly urgent to understand the mechanism linking the changes occurring in the brain with obesity. In this regard, the endocannabinoid (eCB) system which comprises the cannabinoid receptors CB1 and CB2, their lipid-based ligands N-arachidonoyl-ethanolamine (AEA) and 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol (2-AG), as well as the enzymes implicated in their metabolism, plays a critical role in energy metabolism and reward processes [7, 8]. The eCB system is heavily involved in appetite regulation, energy expenditure, and therefore in energy homeostasis [9]. The molecular aspects of the eCB metabolism and signalling have been reviewed elsewhere [10]. Considering the central role of the eCB system, we review its role and complexity in the periphery and in the brain within the context of obesity and weight loss.

Obesity and brain interactions: mechanisms and treatments

Structural and functional changes in the brain associated with obesity

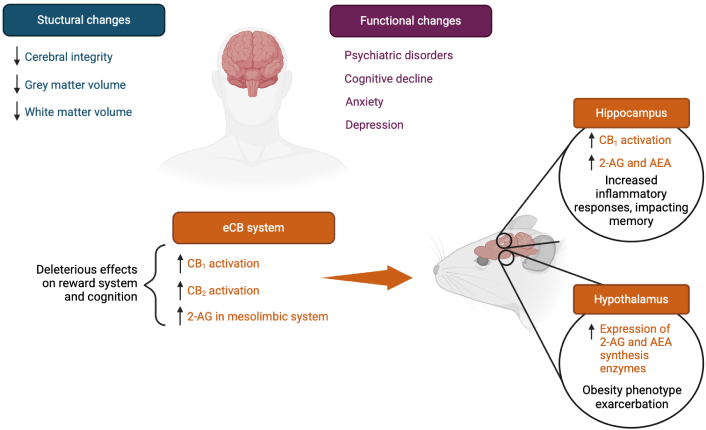

According to several surveys and interview studies, more than half of individuals living with obesity suffer from mood, anxiety, and psychiatric disorders [11–13]. Increasing evidence shows that obesity is associated with changes in the central nervous system (CNS) that translate into cognitive decline [14]. Impaired neurological function in the CNS could result from structural changes in the brain and decreased cerebral integrity [15], as illustrated in Figure 1. This is mainly observed in the hippocampus, a structure responsible for learning and memory [16]. The brain of individuals with obesity is shown to exhibit lower grey matter density compared to lean individuals [17, 18]. Additionally, low-grade inflammation in the brain of individuals with obesity notably contributes to the reduction in white matter’s microstructural integrity [19, 20]. White and grey matter reductions are observed in regions involved in executive function and emotion regulation processes, notably the corpus callosum, the medial prefrontal cortex, and the temporal pole [21, 22]. These results are also observed in patients suffering from obesity or metabolic syndrome, as demonstrated by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showing that body mass index (BMI) is inversely correlated with brain volume [23]. Therefore, obesity is associated with structural alterations in the brain that may contribute to the early onset of neurological diseases [24]. The consequences of obesity on the CNS are highlighting the need for a better understanding of the mechanisms linking impaired cerebral integrity to obesity, notably through the concomitant alterations of the eCB system.

Proposed brain alterations following obesity development. The arrows (↑/↓) indicate an increase or decrease in molecule levels or gene expression, respectively. CB1: cannabinoid receptor 1; CB2: cannabinoid receptor 2; 2-AG: 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol; AEA: N-arachidonoyl-ethanolamine. Created in BioRender. Rakotoarivelo, V. (2025) BioRender.com/e85r233

Association of obesity with the endocannabinoid system

Several animal and human studies have reported that an obesogenic diet or obesity itself results in overactivity of the eCB system in several organs or tissues, such as the hypothalamus and adipose tissue [25–27]. This increased eCB tone consists of an increase in CB1 expression [28], or higher circulating and tissue levels of the eCBs, AEA, and 2-AG [27, 29]. Circulating levels of AEA and 2-AG are strongly associated with body composition, as well as with fat distribution [30]. White and brown adipose tissues possess a high capacity to metabolize AEA and 2-AG [31]. An obesogenic diet consumption in mice was shown to elevate the relative expression of eCB biosynthesis enzymes in these tissues, which might contribute to circulating eCB levels [32]. Moreover, white adipose tissue is involved in the regulation of fat storage, while overproduction of eCBs in obese mice inhibits lipolysis and activates local CB1 [33]. Consequently, the eCB system plays a role in influencing fat deposition and regulating energy homeostasis.

In the brain, eCBs are involved in many biological processes, including the cellular pathways associated with the reward system and motivation to eat [8]. They are known to be highly active in the mesolimbic structures of the CNS, which promotes the craving for palatable foods [34]. More specifically, CB1 signaling activates orexigenic pathways in the hypothalamus [35, 36]. During food deprivation, hypothalamic and limbic AEA and 2-AG levels increase, enhancing neuronal responses that provoke food-seeking behavior through CB1 activation. These levels then decrease upon food consumption [37]. In mice models of diet-induced obesity, the eCB system is upregulated in other brain regions. Elevated levels of 2-AG, apart from the hypothalamus, which controls homeostatic and hedonic food intake [38], are also found in the hippocampus [39], particularly in the dentate gyrus. They contribute to obesity-associated alterations of hippocampal neurogenesis, plasticity, and episodic memory, and thus may indirectly reinforce maladaptive eating behaviors [40]. In the context of a positive energy balance or obesity, the brain eCB signalling is dysregulated, generally showing lower CB1 density, resulting in altered signaling of AEA and 2-AG [41]. In turn, this phenomenon increases feeding activity, reinforcing a phenotype already associated with weight gain in the long term. Notably, direct infusion of eCBs in the hypothalamus of mice induces hyperphagia [42].

Furthermore, CB2 receptor expression is upregulated in mesolimbic structures of obese rats [43]. CB2 is best known for its immune modulatory functions, but it is now suggested that CB2 might modulate energy homeostasis and obesity in rodents [44]. However, its explicit effects on the brain are yet to be fully understood. Thus, consumption of a high-fat diet enhances the reward system mechanisms via CB1 activation, favoring a food preference for this type of diet, as reviewed by D’Addario and collaborators [25]. This results in increased levels of 2-AG levels in the structures of the mesolimbic system and the enhancement of its cellular activity.

Treating obesity: the role of lifestyle changes and bariatric surgery in endocannabinoid-targeted therapies

Since obesity is a multifactorial disease, enabling sustainable weight loss approaches remains complex. These strategies should also be decided in a manner that also addresses obesity-related comorbidities [45].

Targeting the eCB system as a therapeutic target for obesity is a long-lasting and ongoing process. In the early 2000s, research in pharmacological therapies was conducted in order to inhibit CB1 receptors, given their involvement in regulating food intake and energy homeostasis [46–48]. Rimonabant, a CB1 inverse agonist tested in the RIO-Europe clinical trial, was demonstrated to induce significant weight loss in patients living with obesity over a two-year period [48] and to improve cardiometabolic risk factors [46, 49]. However, shortly after the market release, rimonabant was found to cause adverse central side effects in some patients. This drug notably contributes to the development of severe depressive disorders [50, 51], which, as previously noted, is a common comorbidity of obesity. CB1 is, in fact, not only involved in regulating food intake in the brain, but also in mood and stress response [52, 53]. The use of a neutral CB1 receptor antagonist, without inverse antagonist activity, appears to be a safer option for treating obesity, as it reduces food intake and minimizes adverse psychological side effects [54]. Pharmacotherapy that modifies the activity of the central eCB system is thus a promising avenue but requires further investigation [55]. Targeting the activity of peripheral CB1 receptors is also being considered [56, 57]. Notably, since omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids serve as precursors to eCBs, such supplementation could have therapeutic implications for metabolic disorders and feeding behaviour [58, 59].

Obesity management strategies include lifestyle interventions, pharmacological therapies, and bariatric surgery (BS) [60]. To achieve weight loss through lifestyle changes, the body should experience either a higher energy expenditure by physical activity (PA), a lower energy intake by a hypocaloric diet (HD), or a combination of both to negatively impact energy balance, as summarized elsewhere [61, 62]. Combining PA with HD is probably the most effective lifestyle strategy to decrease fat mass, especially in the abdominal adipose tissue depot [61]. Drug therapies, ideally combined with lifestyle changes, are the second line of treatment against obesity. Currently prescribed medications include drugs such as liraglutide, naltrexone/bupropion, and orlistat [63]. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists, such as semaglutide, dulaglutide, or tirzepatide, have recently become available for individuals living with obesity and type 2 diabetes [63]. Notwithstanding their importance in current pharmalogical approaches, we still lack enough literature to address the impact of the drugs on long-term outcomes on the eCB system [64, 65].

BS represents a highly effective therapeutic strategy for treating severe obesity. Its efficacy is demonstrated by substantial and sustained long-term weight loss, combined with significant improvement in various obesity-related comorbidities, and improvement of the patient’s overall quality of life [66]. The commonly performed bariatric procedures described in this review are the laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG), the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), and the biliopancreatic diversion (BPD) with or without a duodenal switch. LSG is a restrictive procedure entailing the removal of 2/3 of the stomach’s total volume [66]. Therefore, satiety occurs more quickly and food intake is reduced [66]. RYGB and BPD modify both the stomach and small intestine, and are considered restrictive and malabsorptive, reducing the absorption of nutrients and micronutrients [67, 68]. Generally, patients eligible for the different types of BS must have a BMI of 35 kg/m2 or higher with at least one major obesity-related disease or have a BMI above 40 kg/m2 without associated diseases [66]. Individuals whose BMI exceeds 30 kg/m2 may be considered eligible for BS if they are afflicted by severe obesity-related comorbidities that are not responding to medical management [66].

Effective weight loss interventions aimed at reducing fat mass might involve changes in eCB system signalling [30]. It is important to note that there are no defined clinical values for fasting and postprandial eCB levels in healthcare, which could also be a relevant clinical indicator. However, given the alterations in the eCB system observed in obesity, weight-loss interventions may help restore circulating levels of AEA and 2-AG and eCB system tone, potentially contributing to success in weight loss and amelioration of obesity-related conditions [69, 70]. The next sections will specifically examine the effects of lifestyle modifications and BS. However, weight-loss strategies that directly target the eCB system through pharmacological interventions are excluded. Indeed, their effects on the eCB system are inherent to their mechanism of action and therefore not relevant to this review. New pharmacological therapies, such as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists, are also excluded due to the current lack of data. Only one recent study reported that liraglutide may reduce levels of N-acylethanolamines, specifically oleoyl-ethanolamine [71]. It is possible that these drug therapies may influence the eCB system in a manner similar to lifestyle modifications or BS.

Impact of lifestyle modifications on circulating endocannabinoids

The significance of eCB mediators in circulation is complex and still not fully understood. Considering that several orexigenic pathways triggered by the eCB system are within the CNS, the following questions arise: are circulating eCBs able to modulate food intake through cannabinoid receptors in the brain? Can brain eCB mediators reach peripheral tissues and influence the circulating levels? Does the concentration of circulating eCBs reflect their tissue concentration as a result of a spillover? Some studies in animal models have suggested that circulating eCB mediators could pass the blood-brain barrier [72–74]. Moreover, in humans with cirrhosis, there is evidence that part of circulating 2-AG comes from the liver [75].

Physical activity

Acute physical activity

Galdino et al. [76] showed an elevation of circulating AEA in rats during an aerobic exercise of 45 minutes. Resistance exercise in rats had significantly increased circulating levels of AEA and 2-AG compared to control [77]. In humans, AEA circulating levels increased in men and women performing a moderate intensity run on a treadmill [78]. The intense exercise was shown to increase plasma AEA in male cyclists, the levels of this eCB being positively correlated with those of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) at the end of exercise and after the 15-minute recovery [79]. It is also observed that elevated levels of AEA immediately after a maximal aerobic exercise test in women fed with a Mediterranean diet compared to women fed with a low-quality diet [80]. Moreover, a 30-minute session of cycling increases plasma 2-AG, even under sleep restriction [81]. Resistance exercises in humans also increase circulating AEA and 2-AG [82]. Moreover, in subjects given naltrexone, an opioid receptor antagonist, or a placebo, two maximal contractions on a hand-grip dynamometer increased AEA in subjects who took the placebo, while 2-AG increased in both groups [83]. Grapov et al. [84] observed conflicting findings, noting reductions in AEA and 2‐AG 10 minutes after acute exercise. Nevertheless, most findings report that acute PA increases circulating eCBs.

Long-term physical activity

Gamelin et al. [85] were interested in the association between PA and eCB after weeks or months of PA in an animal model. In this experiment, male rats were consuming either a high-fat or a standard diet and either did exercising periods on a treadmill for 12 weeks or were sedentary. PA significantly reduced the diet-induced increase in AEA levels. Understanding the influence of PA and diet together on eCB levels poses challenges, due to the intricacies of tissue induced alterations as well as the introduction of PA often counteracting some of these changes [85]. In humans, Fernández-Aranda et al. [86] observed an elevation in circulating AEA levels after six days of moderate-vigorous PA. Sadhasivam et al. [87] observed a significant increase in both eCBs after a 4-day yoga training. Those changes do not appear to be associated with changes in happiness and well-being. However, another study observed no change in AEA and a significant decrease in 2-AG after 80 days of PA leading to weight loss. In another study cohort of healthy participants, a significant AEA decrease was observed after 12 weeks of treadmill three times per week and these changes were associated with the weight loss [88, 89].

A recent systematic review by Desai et al. [90] recently showed that 75% of the 33 studies included observed a significant AEA increase following acute and long-term PA. However, the results for 2-AG were still inconsistent. Their meta-analysis including 10 studies consistently demonstrated a rise in AEA, but also in 2-AG following acute exercise [90].

Acute and long-term PA is associated with an elevation of circulating eCB levels. Higher circulating eCBs are associated with aerobic exercise, which may be associated with the concept of the “runner’s high” [91]. In addition, since eCBs trigger orexigenic pathways [92], it is possible that the elevated levels of circulating eCBs could represent a feedback inhibitory pathway to counterbalance PA energy expenditure.

Hypocaloric diet

Van Eyk et al. [92] conducted a 16-week severe HD intervention (450–1,000 kcal/day) with subjects living with type 2 diabetes. This intervention led to an average weight loss of 16.5 kg and decreased circulating AEA, but did not affect 2-AG levels. However, changes in circulating AEA during the dietary intervention did not correlate with changes in adipose tissue volumes, even though AEA was associated with baseline subcutaneous adipose tissue [92]. Another study observed no change in circulating eCBs in postmenopausal women reaching at least 5% weight reduction after 13–15 weeks of an HD (with instruction to reduce energy intake by 600 kcal/day) [93].

Other studies dig into the type of diet itself more than the hypocaloric effect. For instance, an 8-week Mediterranean diet intervention lowered circulating AEA compared to an isocaloric Western dietary intervention [94]. A shorter (two days) Mediterranean diet intervention following 13 days of low-quality diet produced instead no change in eCB levels, although the levels of eCB-like molecules, derived from oleic, docosahexaenoic, or eicosapentaenoic acids, were increased [30]. Moreover, hedonic eating was associated with increased circulating levels of 2-AG [95], whereas eating in an intuitive manner was associated instead with circulating levels of the 2-AG congeners, 2-eicosapentaenoyl- and 2-docosapentaenoyl-glycerol, which are not ligands of CB1 [59].

Whether the nature of the variation in circulating eCBs following a HD is due to weight loss, the interplay with orexigenic/anorexigenic signaling or the HD itself still needs to be investigated. However, if the HD consists of a change in fatty acid composition, this is likely to result in corresponding alterations of the relative concentrations of eCBs and their congeners containing fatty acids other than arachidonic acid [30].

Combination of physical activity and hypocaloric diet

Following 1 year of multidisciplinary and structured lifestyle intervention involving both an HD and a PA program, circulating levels of 2-AG were reduced, but no change was observed for circulating AEA [96]. A trial included 49 men living with obesity who underwent a one-year-long lifestyle intervention, including PA and an HD. The intervention led to a significant decrease in body weight of 6.4 kg and improved metabolic outcomes. It also decreased circulating AEA by 7.1% and 2-AG by 62.3%. Changes in 2-AG, but not in AEA, were correlated with the decrease in visceral adipose tissue [69]. Soldevila-Domenech et al. [97] observed the same pattern. In subjects following an intervention combining a Mediterranean HD with PA recommendations, which resulted in significant weight loss, AEA and 2-AG levels were decreased after six months. But, over three years, AEA levels were slightly increased, while those of 2-AG remained stable. Changes in AEA were associated with clinically meaningful weight reductions. In sum, combining PA with HD seems to decrease circulating eCBs via weight loss (Table 1). HD may have a stronger impact on circulating AEA and/or 2-AG levels than PA possibly because HD involves reduced intakes of dietary fatty acids that can act as biosynthetic precursors, especially arachidonic acid, for the two eCBs.

Weight loss interventions and circulating eCB levels

| eCB | Lifestyle changes | Bariatric surgery | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA | HD | PA + HD | LSG | RYGB | BPD | |

| AEA | ↑ [76–80, 82, 83, 86, 90]↓ [84, 85] | ↓ [92, 94]Ø [93] | ↑ [97]↓ [69, 97]Ø [96] | ↓ [70, 98, 99] | ↑ [100]↓ [99]Ø [101] | ↓ [98] |

| 2-AG | ↑ [77, 81–83, 90]↓ [84] | Ø [92, 93] | ↓ [69, 96, 97] | ↑ [99]↓ [70]Ø [98] | ↑ [99]↓ [101]Ø [100] | Ø [98] |

↑: increase; ↓: decrease; Ø: no change. eCB: endocannabinoid; PA: physical activity; HD: hypocaloric diet; LSG: laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy; RYGB: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; BPD: biliopancreatic diversion; AEA: N-arachidonoyl-ethanolamine; 2-AG: 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol

Impact of bariatric surgery on circulating endocannabinoids

Weight loss often occurs several months after BS with dynamic shifts in circulating eCBs, which vary in time and between surgical procedures. One year after LSG, sex-specific alterations can be observed in circulating levels of AEA and 2-AG; both eCBs were decreased in women, while only 2-AG was decreased in men [70]. Still, these changes were associated with clinical benefits, such as reduced fat mass.

Mallipedhi et al. [98] conducted a trial where participants underwent either a LSG or a BPD, but no significant difference was found concerning circulating eCBs when comparing all participants. Interestingly, differences were observed in women; AEA levels decreased six months postoperatively. Manca et al. [99] observed that one month after either LSG or RYGB, circulating 2-AG levels were increased and AEA levels were decreased six months postoperatively. The aim of these studies was not to compare the effects of the two types of BS.

It was also observed that a significant elevation in circulating AEA occurred two months after RYGB, while 2-AG levels did not change [100]. A non-significant decrease in AEA and a significant decrease in 2-AG were reported 22 months after RYGB, and this decrease was associated with weight loss [101]. In 11 subjects living with severe obesity who underwent RYGB, eCB levels did not change after one year [102]. However, this study has several limitations, including a small number of participants and the absence of shorter follow-up periods.

In conclusion, circulating eCBs generally tend to decrease postoperatively, especially AEA, and these changes appear to be closely associated with changes in body weight (Table 1). A limitation in studies investigating circulating eCBs after BS is that the surgery itself is accompanied not only by various metabolic changes, but also by a shift in eating habits. Interestingly, in a rat study modeling BPD and single anastomosis duodeno-ileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy, the intestinal levels of 2-AG were found to be decreased, and those of orexigenic eCB congeners, such as 2-palmitoyl-glycerol and N-oleoyl-ethanolamine, were found to be increased [103]. This suggests that BS-induced changes in eCBs and the congeners in the blood may not fully reflect eCB signalling in all tissues.

Table 1 provides a visual summary of the variations in blood levels of the two eCBs, 2-AG and AEA, based on the chosen weight loss methods discussed in the preceding section.

The central endocannabinoid system after weight loss

In rodents [104, 105] as well as in humans [106–108], obesity is known to affect brain homeostasis with repercussions on cognitive health, notably through neuroinflammation mechanisms. This translates into local inflammation that reinforces the pathogenesis of obesity, enhancing hyperphagia and fat accumulation [109]. Furthermore, imaging studies have shown that obesity negatively impacts gray matter volume or brain activity in certain regions responsible for decision-making and the reward system (Figure 1) [110, 111]. This could further promote overeating, the consequence of the diminished reactivity of the brain reward system in response to food consumption [18].

In mice, weight loss has been shown to result from modifications to the central eCB tone. This effect is observed not only with the administration of CB1 receptor antagonists [112, 113], but also through the inhibition of specific receptors or enzymes of the eCB system [114, 115]. However, how the central eCB system adapts following weight loss remains poorly understood, and the existing literature on the subject is limited. In human studies, the central eCB system is even more challenging to study and difficult to assess with current medical tools. The following sections will explore the potential mechanisms linking the central eCB system to weight loss, with a particular emphasis on its role in the reward system.

Improvement of brain homeostasis after weight loss

Brain connectivity refers to communication between different brain regions. Connectivity can be structural, involving physical interconnections in white matter tracts, or functional, referring to the interplay between neuronal activities in different brain regions [116]. Weight loss involves changes in the connectivity of the reward system and structures that regulate appetite.

Weight loss interventions based on lifestyle modifications are known to improve brain connectivity within several cerebral regions. The combination of HD and PA increased neural connectivity related to food-cues reactivity between the left precuneus/superior parietal lobule and bilateral insula [117]. Moreover, patients with obesity who underwent weight loss through lifestyle modifications showed greater activation of the right medial prefrontal cortex and left precuneus when stimulated by images of foods than behavioural dieters [118]. An 8-week intervention with a very low-calorie diet (± 600 kcal/day) decreased blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signals in brain regions associated with feeding behaviour and reward processing (i.e., insula, orbitofrontal cortex) in adults living with obesity [119]. These studies suggest a shift in how self-referential information about food intake and hunger cues is processed in patients who intentionally seek to lose weight. Using PA alone to diminish body weight also improves brain plasticity in overweight or obesity, by increasing grey matter density in the left hippocampus, in the insular cortex, and in the left cerebellar lobule [120]. The same study also found that serum BDNF concentrations increased after weight loss [120]. BDNF being a key neurotrophic factor supporting neural growth [121], this elevation could contribute to enhanced brain plasticity and connectivity. Ultimately, HD and PA led to better learning and memory abilities in the long-term, suggesting that alterations of neural activity caused by obesity are partially reversible by lifestyle modifications.

BS also helps reverse the adverse effects of obesity on anatomical and structural components of the human brain, as well as on brain functional connectivity. Specifically, functional MRI (fMRI) and diffusion tensor imaging measurements were used to investigate sequences of alterations in the function and structure of frontal-limbic circuits in patients living with obesity who underwent LSG [122]. The results also demonstrated that LSG significantly increased functional and structural connectivity of the prefrontal cortex, a brain area involved in the inhibitory control and self-regulation, one and six months post-surgery [122]. The orbitofrontal cortex and its neural connectivity to the limbic regions (amygdala, hippocampus, and medial thalamus) are decreased in individuals with obesity who have undergone LSG, suggesting the involvement of the orbitofrontal cortex in eating behaviours [123]. This decrease is also correlated change in the BMI of the participants [123]. Weight loss induced by LSG was also reported, using structural MRI one month post-surgery, to increase the cortical thickness in many brain regions implicated in executive control and self-referential processing [124]. It has been demonstrated that the types of BS discussed in this current review (i.e., LSG, RYGB, and BPD) improve short-term spontaneous neural activity in obesity, which is measured using fMRI and defined by fractional amplitude of low frequency fluctuations [125]. Although the authors of this latter study were unable to compare the brain improvements among the three types of BS, they did observe a global increase in grey matter density, which was positively associated with the increased fractional amplitude of low frequency fluctuations four and twelve months post-surgery [125]. The volume of white and grey matter in the brain’s left hemisphere also increased in adults with severe obesity who underwent RYGB or LSG [126]. Another study compared the effects of LSG and RYGB six months postoperatively; while RYGB led to a significantly higher weight loss than LSG, the benefits on cognitive function were comparable [127]. These results suggest that CNS improvements following different types of BS are comparable in the short and long term. Interestingly, six months to a year after RYGB surgery, widespread dynamic plasticity in white and grey matter density of specific brain regions were highlighted, suggesting surgery-induced behavioural adaptations in sensorimotor functions (frontoparietal cortex, cerebellum) and in cognitive-emotional functions (prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala) [128].

In sum, these results suggest that, regardless of the surgical procedure, BS can reverse some of the detrimental impact of obesity on the brain and might improve dietary patterns. While lifestyle modifications also enhance neural activity, BS appears more effective, with rapid and more widespread effects across various brain regions. Although both weight loss methods show effectiveness, differences in brain connectivity indicate distinct underlying mechanisms. Improvements in brain homeostasis are likely to extend to the central eCB system and its role in food intake regulation.

The reward system: a driving force behind the endocannabinoid system?

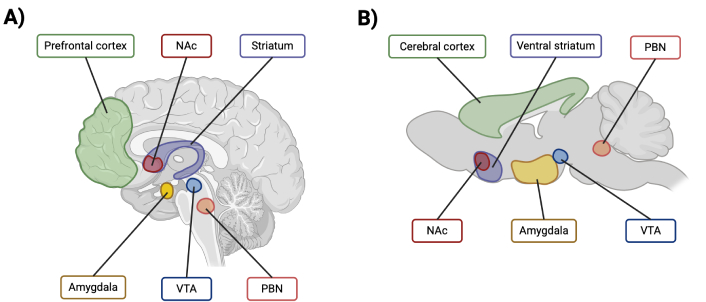

The reward system, involved in hedonic eating, is a complex network of neural circuits in the brain that regulates motivation, pleasure, and reinforcement to eat palatable foods [129]. Hedonic eating differs from homeostatic eating, in which the latter regulates energy balance for survival rather than being driven by pleasure or learned experiences [130]. The brain areas that constitute the reward system are notably the ventral tegmental area, the amygdala, the nucleus accumbens, the ventral striatum, the parabrachial nucleus, and the prefrontal cortex (Figure 2) [8, 131]. Dysfunctions in these areas can contribute to excessive eating, favoring the development of obesity. Imaging studies have shown that, in the presence of obesity, the reward system brain circuits are more solicited when subjects are exposed to palatable foods [132]. In women, pictures of high-calorie foods activated significantly more brain regions mediating motivational and emotional responses to food stimuli [131]. Thus, foods with a high energy density have the potential to generate excessive motivation for hedonic eating, promoting a positive energy balance.

Visual representation of the main brain regions implicated in the reward system in A) human and B) mouse. NAc: nucleus accumbens; VTA: ventral tegmental area; PBN: parabrachial nucleus. Created in BioRender. St-arnaud, G. (2025) BioRender.com/r88b546

Both eCBs play a role in the brain reward system. They stimulate feeding, but they also contribute to the response to palatable foods [8]. The eCB system influences the reward system by regulating dopaminergic control of reinforcement and reward [133]. In the ventral tegmental area of the mesolimbic system, dopamine neurons express the CB1 receptor. By binding to CB1 receptors on presynaptic dopaminergic neurons, eCBs alter the ventral tegmental area activity and influence dopamine release [133, 134]. This regulation reinforces reward-related behaviours, increasing the likelihood of repeating pleasurable actions such as eating or reproduction. Therefore, peripheral, but especially neuronal eCB signalling, is involved in determining the hedonic value of food intake. Defects in these systems may alter body weight regulation [130]. Both eCB receptors, CB1 and CB2, as well as their main ligands (AEA and 2-AG), are found in hypothalamic and mesolimbic brain regions that regulate hedonic feeding [36]. Direct injection of eCB in the brain of rodents induced a positive emotion linked to food ingestion, while CB1 receptors blockade by the inverse agonist AM251 reversed this effect, supporting the role of eCBs as regulators of hedonic eating [135]. In obese individuals, circulating 2-AG levels increase during, or even in the anticipation of consumption of palatable foods compared with non-hedonic feeding-related foods [136, 137]. This suggests an alteration in eCB control of hedonic feeding in obesity. In satiety, postprandial circulating AEA levels in healthy participants are associated with increased connectivity between the lateral hypothalamus and the ventral striatum, two brain regions involved in reward and salience networks [138]. This phenomenon was also observed for fasting circulating levels of AEA, but not of 2-AG, in healthy participants. This implies that AEA levels also respond to homeostatic changes and are connected to reward and salience networks [138]. Indeed, fMRI showed that, after a rewarding stimulus, the activity of the putamen is positively correlated with fasting AEA [139]. Taken together, these studies suggest that peripheral concentrations of both AEA and 2-AG may impact eCB signalling activity in the reward system, potentially acting indirectly through peripheral targets (e.g., the gut). However, only 2-AG in circulation shows an association with elevated body weight.

The reward system responds differently to lifestyle interventions compared to BS. Comparing the efficacy of a very low-calorie diet to RYGB revealed that four weeks after BS, brain regions implicated in hedonic responses were significantly less activated [140]. A similar outcome was obtained in a study by Agarwal et al. [141], where BS, such as LSG and RYGB, had greater effects on improving postprandial activation of food-related neural circuits than a dietary-induced weight loss. Patients who underwent BS tended to prefer higher quality foods, favouring protein and/or carbohydrate intake and a decrease of fat intake [142]. These changes in food preference can be attributed to modifications of the reward system, which may be mediated in part by the eCB system [143]. In humans, one study showed that satiety hormones were enhanced after BS, supposing a causal mechanism for improved reward system responses [144]. The secretion of satiety and appetite hormones may be closely linked to eCBs, as they are involved in control of nutrient intake, metabolism, and storage [7, 145]. Indeed, in a rat model of BPD, changes in 2-AG levels and anorexigenic eCB-like mediators were, respectively, negatively and positively associated with changes in peptide YY levels [103]. Therefore, eCB signalling might help regulate reward responses by interacting with multiple signalling pathways of hormones following BS. However, it is important to note that the identification of the exact mechanisms would require further study.

To conclude, according to the evidence presented in this review, it is possible that, following BS or weight loss through lifestyle interventions, a long-term decline in circulating levels of AEA and 2-AG is associated with improved reward system responses in the brain. However, BS seems more efficient in improving reward responses in the brain than lifestyle modifications alone. Further research is needed to fully understand the mechanisms in which eCB signalling interacts with the reward system, especially on a molecular and cellular level.

Conclusions

In conclusion, circulating eCB levels are modulated by weight-loss interventions, such as lifestyle interventions and BS, in both animal models and humans. Many studies have reported a decrease in these lipid mediators following weight loss, likely due to their positive correlation with fat mass. However, the studies reviewed show varied modulation of eCBs following weight loss, highlighting the need for further research to identify the factors contributing to these inconsistent findings. A study associating circulating levels of eCBs with those in the brain in the context of obesity and weight loss would be necessary. It would also be relevant to associate brain connectivity and homeostasis with brain levels of AEA and 2-AG, to better understand their role in cognition. Such studies on this topic would enhance our understanding of the eCB system and its role during weight loss, particularly in the context of severe obesity and BS, which appears to result in rapid and marked improvement in cognitive function. In our perspective, BS could be a more effective treatment than lifestyle modifications for rapid improvement in brain homeostasis and potentially regulating the eCB system in individuals living with severe obesity.

Abbreviations

| 2-AG: | 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol |

| AEA: | N-arachidonoyl-ethanolamine |

| BMI: | body mass index |

| BPD: | biliopancreatic diversion |

| BS: | bariatric surgery |

| CB1: | cannabinoid receptor 1 |

| CNS: | central nervous system |

| eCB: | endocannabinoid |

| fMRI: | functional magnetic resonance imaging |

| HD: | hypocaloric diet |

| LSG: | laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy |

| MRI: | magnetic resonance imaging |

| PA: | physical activity |

| RYGB: | Roux-en-Y gastric bypass |

Declarations

Author contributions

GSA: Conceptualization, Methodolody, Investigation, Visualization, Writing—original draft. TR: Conceptualization, Methodolody, Investigation, Writing—original draft. AV and VDM: Funding acquisition, Writing—review & editing. VR: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Visualization, Writing—review & editing. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Canada Research Excellence Chair in the Microbiome-Endocannabinoidome Axis in Metabolic Health (CERC-MEND) (to VDM, 2017–2024). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

Publisher’s note

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.