Abstract

Nanoscience and nanotechnology have experienced a dizzying development in recent years, which undoubtedly contributes to various fields of human activity such as biotechnology, engineering, medical sciences, food security, etc. This impact has taken place in the food field too, especially in the role played by nanomaterials (NMs) for producing quality nano-based products, food shelf life, and target-specific bioactive delivery, since traditionally the presence of these materials was not at the nano-scale. Anyway, switching these materials to their nano-forms carries benefits as well as risks that must be assessed. Thus, the evaluation of the presence and quantity of these NMs must be achieved based on reliable physic-chemical-analytical information; hence the impact that analytical chemistry should have in the nanoscience to develop validated methodologies for its control. Currently, this fact represents a significant challenge due to the difficulties of measuring entities at the nanoscale in complex samples such as those of food. This review critically explores these analytical challenges, their difficulties, and their trends within the general framework of NMs’ analytical monitoring in food.

Keywords

Nanomaterials, food, characterization, analytical nanometrology, size-based separation techniques, surface enhanced spectroscopiesIntroduction

A growing attention is currently being paid to the “nano-world”, which is represented by entities, called nanomaterials (NMs), with at least one dimension lower than 100 nm, and with interesting physicochemical properties applicable to a multitude of fields such as cosmetic, electronic, environmental, industrial food and biomedicine [1]. This limiting size is accepted as the separation border between the nano- and micro-world. Science and technology applied to materials have been so far consubstantial with the development and welfare of society; hence, nanoscience & nanotechnology currently emerges as an increasingly important trend within it. This special interest in NMs arises from the improvement of some nanoscale properties with respect to the properties of analogous bulk materials [2]. Such behaviour is due to the appearance of the “quantum size effect” from the electronic wavefunction, to the limited physical dimensions of the nanoparticle (NP), being this effect just limited to the nanoscale [3, 4]. Owing to this confinement at the nanoscale, the phonons on which thermal, optical, and conductive properties depend, will impart distinctive characteristics to the NMs compared to the unconfined and macroscopic counterparts, with a like-photons behaviour. Under this situation, a new set of discrete quantum energetic states will be established with further energetic available transitions (and hence new or potentialized properties) [3].

Additionally, there is a significant rise in the surface-volume ratio, which entails a higher number of atoms on the surface and, thus, a common increase of reactivity because most of the molecules, ions, or other components appear on the NP surfaces. As a result, properties such as colour, solubility, conductivity, and reactivity among others become completely different in the nano-world with respect to the micro/macro-world [5–7].

On the other hand, other relevant properties of some metallic NPs like luminescence and size-dependent colour come from photon-photon interactions at nanoscale range, which are in turn related to localized plasmon resonance effects [7]. Thus, when the particle size is decreased, it affects the already existing gap energy between the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) levels, changing in this way the energy and frequencies emitted by the NP photons. In turn, owing to interactions between NPs and the surrounding particles in diverse media, it is possible to observe different colours for such NPs with both different sizes and environments [6, 7].

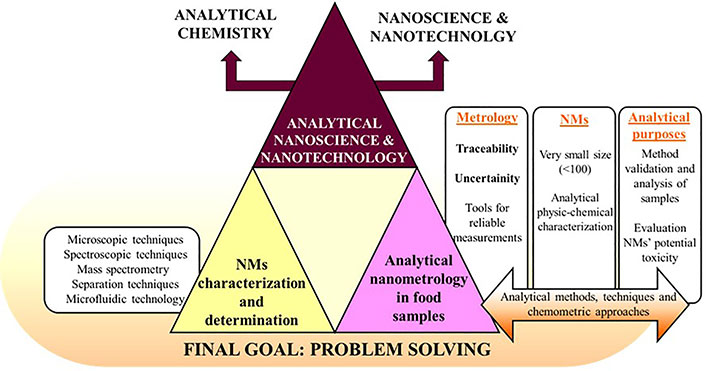

Nanotechnology is besides a multidisciplinary area as Feynman’s statement confirmed (1959), where he expressed that some scientific disciplines such as chemistry and biology would be more deeply studied/researched if they could be manipulated and observed at the atomic scale [8]. Thus, this review tries to give a critical vision of the issues related to the implementation of NMs in food field, also providing a systematic assessment of their potential risks as well as taking a step forward by including the most widely used applications and characterization techniques within this field. With this aim Figure 1 tries to display an informative table of contents (TOC) diagram about all the addressed items in this review.

Impact of nanotechnology on the food field

Undoubtedly, an amazing number of nanotechnology applications in food science are revolutionizing the food industry, highlighting the following topics [9–11]:

(1) Increasing the self-life of food and improving its quality.

(2) Bioactive fortification with controlled release by means of nanocarrier systems.

(3) Colouring, flavourings, adding nutritional additives, and modification of food structures and textures.

(4) Antimicrobial agents and detection of chemical alterations by using intelligent packaging systems.

The food field is, of course, one of the important areas where nanoscience and nanotechnology have a wide incidence. Thus, there are a great number of current applications of both inorganic and organic NMs in food, food additives, and food-contact materials. It summarized in Table 1 the most used NMs in food field so far and where they are applied.

NMs commonly used in food industry

| ENMs | Application | Claim | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 NPs, TiO2 NPs, Fe2O3 NPs, Ag NPs | Food additives, food ingredients | TiO2 (food colorant E171) has been regulatory and used as colouring agent and flavour enhancer in food products. SAS (often referred to as SiO2) is typically used as anticaking agent to keep fluids in powder products and as carrier for flavours and fragrances in food. Ag NPs or nanosilver-coated polymers are widely applied in food packaging because of their broad-spectrum antibacterial activity against pathogenic bacteria. Fe2O3 is worldwide used as food additive for colouring in desserts, cakes, salmon, meat paste, etc. | [12–14] |

| Nanocomposites, ZnO NPs, AgO NPs | Food contact materials | Nanocomposites have outstanding gas-barrier properties (reducing the entry of O2 and other gases, thermal buffering, etc.) to modify plastic characteristics as active food packaging components. ZnO NPs are incorporated into food contact materials as UV-blocking and antimicrobial agents | [15–18] |

| NOMs such as nanoemulsions, nanomicelles, liposomes, etc. | Nutritional supplements | Optimal nanocarrier systems of hydrophobic substances for a higher and faster intestinal and dermal resorption and penetration of bioactive ingredients (Aquanova, NovaSOL®, Pharmanex®, NutraLease) | [19–24] |

| Nanoformulations with pesticides at nanoscale Nanoencapsulated nisin | Pesticides and biocides | Encapsulation of pesticides and biocides using NMs to improve their physic-chemical properties and to control their widespread use to ensure food safety. Nisin (E234) is the best-known bactericide so far, being used a preservative against food-borne pathogens | [25–29] |

ENMs: engineered NMs; Ag NPs: silver NPs; SAS: synthetic amorphous silica; UV: ultraviolet; NOMs: nanostructured organic materials

However, other important aspects as their toxicity and environmental damage must be also considered, since derived from their unpredictable behaviour as NMs are able to cross biological membranes, tissues, and organs that their analogues at the macro-scale normally cannot. Thus, NMs can reach the bloodstream through several pathways, and once there, they can be carried around the body reaching organs and tissues, e.g., brain, heart, liver, kidneys, spleen, nervous system, bone marrow, etc., which may entail a rational inherent concern [30–32].

Considering the applications previously cited, the present and future of NMs research should also focus on the interaction between the NPs and living beings. In this context, it is necessary to develop accurate and robust methodologies for the characterization of physiochemical properties of NPs as well as for their quantification in vivo conditions. However, there is almost no global standardized methodology able to assess the toxicological effects of NMs in commercial applications [33, 34].

Thus, although there is no doubt about the great benefits that NMs bring to food and food industry (as Table 1 displays), they also involved new threats to food sector. As before mentioned, their risks are associated with the potential toxicity to human health and to environmental damages, thereupon the safety of the NMs has attracted attention in line with their increasing use [33]. As with any other new discipline, it is quite unregulated, so it is necessary for information-gathering (studies about toxicity, legislation, customer information, etc.) lacking the legal and scientific tools, as well as resources to oversee the exponential market growth of nanotechnology [35].

To ensure the appropriate balance between benefits (competitiveness for the agri-food sector) and risks is necessary to have reliable analytical information on the presence and amount of NMs in food samples. With this aim, validated analytical methodologies for monitoring NMs in food are needed. So, from a broader point of view, the role of analytical science associated with NMs-foods can be summarized in the following outstanding points:

(1) Characterization of NMs used in the food industry (synthetic or natural).

(2) Quality control of products and foods containing NMs with nutritional or healthy interests.

(3) Detection/determination of NMs in food because of their potential toxicity.

(4) Production of reliable working standards involved in the corresponding analytical methods.

To begin these tasks, two fundamental goals within analytical nanoscience and nanotechnology can be distinguished. The first one is related to the characterization of NMs because they will be used for other purposes. The second one is the identification/determination of NMs in particular samples. Both aspects will be next discussed in this review.

The characterization issues on NMs

There is a vast amount of information related to NMs, for instance, size, size distribution, agglomeration, shape, structure, composition, surface charge, and concentration when they are present in samples. So, it is important to know these parameters about the NMs-based formulations used in food industry, as well as the risks associated with them through accurate and appropriate analytical techniques to provide a proper and exhaustive analytical characterization. From an analytical point of view, there are many instrumental techniques to supply this information, primarily microscopic, diffraction, spectroscopic, and instrumental separation techniques. Therefore, it is important to match the type of needed information with specific technique(s) [36].

Currently, it does not exist a single analytical tool able to provide all meaningful information about NPs, since depending on the NPs’ nature, we should use a combination of different analytical techniques [36].

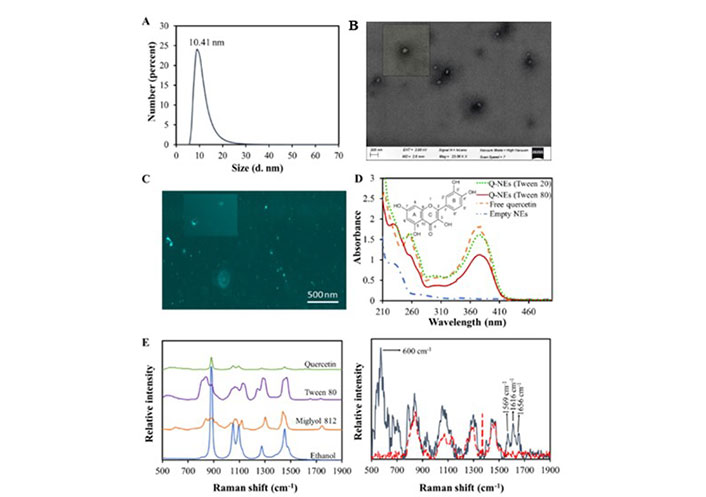

The Table 2 provides detailed and specific referenced information about the huge number of analytical tools commonly used for the analytical physic-chemical characterization of NPs. They have been there classified into microscopic [37–48], spectroscopic [37, 38, 40–42, 44, 49–54], and mass spectrometry techniques [40, 42, 55–57], although these last ones are usually coupled with those based on size-separation criteria [42, 58, 59] or either to other ionization tools such as electrospray ionization (ESI), matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI), laser desorption/ionization (LDI) and inductively coupled plasma (ICP) [42, 55] (all these references are also displayed in Table 2). Other emerging technologies for the analytical characterization of NMs such as microfluidics and size separation techniques will be commented on later in the last section of this review, which is relative to future perspectives and challenges. On the other hand, as an illustrative example, Figure 2 shows a full physic-chemical characterization of NOMs, specifically based on quercetin-nanoemulsions (Q-NEs), implemented as nutraceutical supplement [60] by means of diverse spectroscopic and microscopic techniques.

Overview of techniques for the analytical characterization and determination of NMs

| Classification | Techniques | Relevant insight | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microscopic techniques | AFM, SEM, TEM, NSOM, SPM, CLSM, STEM, XRM, STXM | Particle size, distribution morphology, surface texture, electrical, shape, and aggregation state | [37–48] |

| Spectroscopic techniques | XRD, XRF, XAS, XPX | Chemical analysis of surfaces | [37, 41, 42] |

| SLS, DLS, NS, SAXS, LIBD, Raman spectroscopy, LIF, NMR, photon correlation spectroscopy | Particle size, distribution morphology, surface texture, electrostatic charge, shape, and aggregation state | [37, 38, 40–42, 44, 51–53] | |

| Raman spectroscopy, LIF, UV-Vis, infrared spectroscopy, NMR | Chemical characterization | [37, 38, 40–42, 44, 51, 53, 54] | |

| Mass spectrometry | TOF, QLIT, IT, single quadrupole, QQ, QTOF | Chemical characterization | [40, 42, 55–57] |

| Microfluidic technology | NMs-based microfluidic sensing | Optical, electrical, magnetic, and acoustic detection | [61–67] |

| Microfluidic-based NMs synthesis | Synthesis of 0D, 1D, 2D, 3D NMs | [64–71] | |

| Separation techniques based on size criterion | SEC, HDC, FFF | Separation and quantification of NMs | [72–86] |

| Separation techniques based on chemical structure criterion | CE modes, IMS/DMA | [87–89] |

AFM: atomic force microscopy; SEM: scanning electron microscopy; TEM: transmission electron microscopy; STEM: scanning TEM; NSOM: near field-scanning optical microscopy; SPM: scanning probe microscopy; CLSM: confocal laser scanning microscopy; XRM: X-ray microscopy; STXM: scanning transmission XRM; XRD: X-ray diffraction; XRF: X-ray fluorescence; XAS: X-ray absorption; XPX: X-ray photoelectron; SLS: static light scattering; DLS: dynamic light scattering; NS: neutron scattering; SAXS: small-angle X-ray scattering; LIBD: lased-induced breakdown detection; LIF: lased-induced fluorescence; UV-Vis: ultraviolet-visible; NMR: nuclear magnetic resonance; TOF: time-of-flight; IT: ion trap; QLIT: quadrupole linear IT; QQ: triple quadrupole; QTOF: quadruple TOF; SEC: size exclusion chromatography; HDC: hydrodynamic chromatography; FFF: field flow fractionation; CE: capillary electrophoresis; IMS/DMA: ion-mobility spectrometry/differential mobility analysis

Characterization of Q-NEs: A) DLS number distribution diagram; B) SEM image of Q-NEs; C) CLSM images in absence and presence (inset) of irradiation; D) UV-Vis spectra of Q-NEs with Tween 80, Q-NEs with Tween 20, empty nanoemulsion (NE-blank) and free Q; E) (left) Raman spectra of individual components and (right) the same for empty NE (red dashed line) and Q-NEs (grey solid lines)

Note. Reprinted from “Distinctive sensing nanotool for free and nanoencapsulated quercetin discrimination based on S,N co-doped graphene dots,” by Montes C, Villamayor N, Villaseñor MJ, Rios A. Anal Chim Acta. 2022;1230:340406 (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0003267022009771?via%3Dihub). © 2022 Elsevier B.V.

In addition to the analytes of interest, the sample matrix can contain other substances that could shift out of range the selected analytical signals and some of which may show up naturally as NMs. This may occur due to the existence of assorted thermodynamic equilibria, generation of diverse nature corona around NPs, reaction of some redox-sensitive particles, or either the presence of natural NPs. So, the knowledge of multiple factors may be required to optimize, develop, and validate robust methodologies to characterize NPs without altering their native features in any way [90–93].

Analytical nanometrology for food samples

The second side is the identification/detection/determination of NMs in specific samples, and this goal is frequently referred to as analytical nanometrology (ANM) [94]. Different analytical techniques, already included in Table 2, can be used. In many cases, the objective is NPs of inorganic nature (some of them synthetic NMs, ENMs), although growing attention is being paid to organic NMs (especially in food and biomedical fields). Obviously, food safety is indeed a contemporary issue within the implementation of NPs in food. Consequently, it is acknowledged that ingredients that are typically regarded as safe at the macro level may not be safe at the nanoscale. When NMs reach the human body, they may be recognized by the immune system, leading to unwanted biological responses. This is due to the ability of NPs to interact with cells, proteins, and even DNA, eventually causing genetic mutations. This genotoxicity may be caused by direct damage (direct interaction with DNA) or by indirect damage by reactive oxygen species (ROS). The generation of ROS has been also studied in “in vivo” conditions [33], where these oxidation processes of biomolecules have driven tissue degradation, which in turn led to carcinogenesis events among others [95, 96].

Nevertheless, the host response will depend on the NM’s interaction with any component of the body (e.g., cells, lipids, and proteins) and the NMs’ features. Therefore, appropriate testing methodologies are needed for the safety control of food containing (or potentially containing) NPs. Regarding this, it must be recognized the disproportion between the investment devoted to the development of new products (e.g., NMs) versus that one spent on researching the safety of these products.

Finally, the toxicity of the NMs greatly depends on the level of human exposure to them, which is closely related to the bare specific area and the concentration usage. Thus, Table 3 summarizes ENMs used in the food field, their discrete reported toxicity from diverse “in vivo” studies, as well the appropriate European legislation to control their application.

In vivo toxicity studies for different NPs and relevant European legislation

| NP | Testing material | Toxicity | Purpose in food | Reference | European legislation applicable to NMs in food |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag NPs | Nitrifying bacteria, human colon carcinoma cells, human umbilical vein, endothelial cells | Oxidative stress is associated to decrease viability, inhibition of mitochondrial activity, and initiation of apoptosis | Food contact, packaging materials, and food additives | [96, 97] | Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008: for food additives; Regulation (EU) No 528/2012: biocides |

| TiO2 NPs | Anaerobic gut bacteria, human gastric epithelial cells, human peripheral blood, mononuclear cells | Potentially carcinogenic, DNA damage, oxidative stress, chromatin condensation, and eventual cell death via apoptosis | Food additive (E171 or INS171) | [98–100] | Regulation (EC) No 1334/2008: on food flavourings |

| ZnO NPs | Human pulmonary adenocarcinoma cell, male IRC mice | Oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction | Food packaging | [101, 102] | Regulation (EC) No 2283/2015: on novel foods |

| SiO2 NPs | Sprague-Dawley rats, human bronchoalveolar carcinoma cells | Fibrotic lung disease, lung cancer, emphysema and pulmonary tuberculosis, autoimmune disease, systemic sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and chronic renal disease | Packaging additive (E551) | [103–105] | Regulation (EC) No 450/2009*: active and intelligent materials intended to come into contact with food |

| NOMs to encapsulate bioactive compounds | Cells obtained from liver tissue of patient with hepatocellular carcinoma | Prevent cell division, hinder cell proliferation, damage DNA and biological systems, eventually lead to cell death; raising concerns over acute and chronic toxicity and related problems | Food encapsulation, food processing, food supplement, active material intended to meet contact to food | [36, 106, 107] | Regulation (EC) No 1925/2006: for fortified foods |

| Fe2O3 | Blood lymphocytes from healthy humans | Generation of ROS, changes in function of vital organs, in cellular morphology, and induction of apoptosis | Food additive, enzyme immobilization | [108] | Regulation (EU) No 10/2011*: on plastic materials and articles intended to come into contact with food; Regulation (EC) No 1332/2008: on food enzyme |

EC: European Commission; EU: European Union; * Although both regulations are not directly applicable to NMs there is a reference to “New technologies that engineer substances in particle sizes that exhibit chemical and physical properties significantly different from those at a larger scale, for example NPs, should be assessed on a case-by-case basis as regards their risk until more information is known about such new technology. Therefore, they should not be covered by the functional barrier concept.”

Thus, silver is a blatant example of a regulated additive in Europe (E174), as already cited in Table 3. Sometimes, it is occasionally employed as NPs (Ag NPs), which enhance the quality, safety, and shelf-life of packaged food and drinks due to their antibacterial capabilities, but they may have potential health hazards which are not yet fully understood and not entirely regulated as a result. Hence, it is crucial to monitor their presence in dietary samples (silver-coloured pearls, used as decoration in pastry for instance). Recent research is based on the chemiluminescence of luminol/Ag+ in alkaline medium induced by the presence of Ag NPs. This method involves easy monitoring, since is a straightforward qualitative screening for Ag NPs in pastry manufacturing, whereas asymmetric-flow FFF (AF4) coupled with inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) was used to confirm the findings [109]. This approach has been also applied to control the migration of Ag NPs from food containers into food simulants [110].

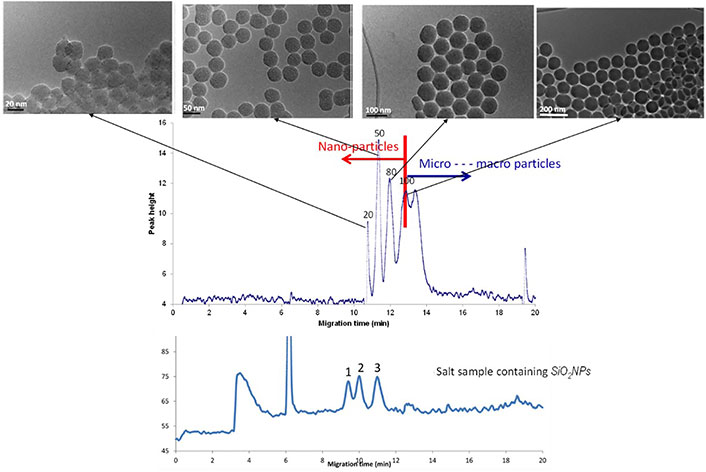

Another noteworthy example in this area is SiO2 NPs. According to the specific matrix, there may be different maximal allowed levels for silica, an EU-authorized food additive (E551). Thus, 50 g kg–1 for dry powdered emulsions and flavouring preparations or 10 g kg–1 in nutrient preparations for infants feeding and young children. It is also used for beer and wine clearance, and as an additive in thickened pastes and salt samples. The main issue associated with its use as NPs lies in what performed studies reporting about some potential real hazards (pregnancy and coagulopathy difficulties), but the current legislation does not distinguish between macro- and nano-silica yet. This highlights the importance of monitoring SiO2 NPs in potentially containing meals. With this aim, CE coupled to an evaporative light scattering detector (CE-ELSD) was used to develop an approach for controlling their presence in salt samples, a very common ingredient in a wide variety of foods [88]. The electropherogram obtained for a blend of nano- and micro- SiO2 particles of different sizes together with their TEM confirmation is displayed in Figure 3.

Electropherogram obtained by CE-ELSD displaying the separation of silica NPs from silica microparticles of different sizes, as well as the analysis of a salt sample containing SiO2 NPs

Note. Adapted from “Analysis of silica nanoparticles by capillary electrophoresis coupled to an evaporative light scattering detector,” by Adelantado C, Rodríguez-Fariñas N, Martín-Doimeadios RCR, Zougagh M, Ríos Á. Anal Chim Acta. 2016;923:82–8 (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0003267016304056?via%3Dihub). © 2016 Elsevier B.V.

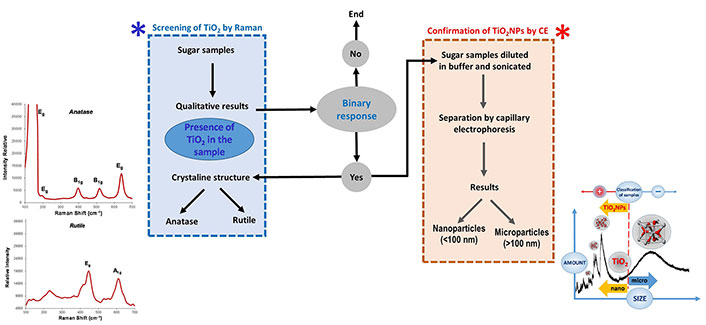

The study of sugary meals containing TiO2 NPs is another meaningful topic in food industry. These NPs have demonstrated potential risks to humans. TiO2 NPs enter the blood and lymph after ingestion where they can reach sensitive target areas (bones, brain, liver, and heart). As NPs present cytotoxic, genotoxic, and carcinogenic effects. However, TiO2 is widely used in a variety of areas such as cosmetics, ceramics, catalysts, etc., including food field, where it is regarded as a food-grade additive (E171 in EU). The legislation does not distinguish again between micro- and nano-forms, requiring the development of accurate analytical methodologies to identify and quantify TiO2 NPs in foods. A feasible screening-confirmation strategy has been recently developed for the analysis of TiO2 NPs in sugar and sugar-containing products. Raman spectroscopy was employed to perform a direct screening of samples to determine whether TiO2 NPs were present or not. Then, positive samples were examined to know about the crystallographic structure of TiO2 (anatase or rutile), which were next confirmed by CE, reporting their nano- or micro-size too [89]. This strategy is summarized in Figure 4. Thus, sugar samples were initially checked using Raman spectroscopy to determine the presence of TiO2, being also able to discriminate between its two crystallographic forms through their distinctive scattering bands. When there was a positive result for TiO2 in sugar samples, it was required to confirm its presence (total or partially) as TiO2 NPs. This last step was carried out by CE since the electropherogram allows us to discern between nano- and micro-forms of this compound.

Diagram about the analytical screening-confirmation strategy to identify the presence of TiO2 NPs in sugary products

Note. Adapted from “Analytical nanometrological approach for screening and confirmation of titanium dioxide nano/micro-particles in sugary samples based on Raman spectroscopy – capillary electrophoresis” by Moreno V, Zougagh M, Ríos Á. Anal Chim Acta. 2019;1050:169–75 (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0003267018313096?via%3Dihub). © 2018 Elsevier B.V.

ZnO NPs characterization is also relevant for the food field. It can be used in the packaging linings of food cans for meat, fish, maize, and peas to preserve colors and prevent rotting. Additionally, they can be added as food additive as a source of zinc used to fortify cereal-based foods. According to reported research, large concentrations of ZnO are harmless, but when they are replaced by NPs of the same material (ZnO NPs), they penetrate cells, being intracellularly dissolved and triggering an acute cytotoxic process, displaying a molecular mechanism whose chemical basis is thoroughly outlined [111]. Hence the interest for their analytical control in food. Regarding it, single particle ICP-MS (sp-ICP-MS) has proven to be a highly effective technique to detect and characterize the presence of ZnO NPs in cereal-based foods [112].

Recently, NOMs like nanoemulsions, nanoliposomes, and nanomicelles among others, are emerging as very helpful nanotools for encapsulating lipophilic systems or acting as nanocarriers for biologically active compounds. Nutraceuticals are food ingredients that provide benefits since they are thought to prevent chronic diseases and enhance human health. However, their usefulness in food industry is constrained due to their weak water solubility, low bioavailability, pH sensitivity, and easy degradation in adverse media such as environmental gastric conditions. Many nanotechnological approaches have arisen to overcome all these limitations, such as the already mentioned nanosystems with the aim to exploit their therapeutical effects. An extensive revision was published on the analytical control of nanodelivery lipid-based systems for the encapsulation of nutraceuticals [113]. In addition to the intrinsic difficulty in characterizing NOMs, especially when they are present in complex matrices such as food, the authors noted the major challenges from an analytical point of view: sampling and sample treatments (separation procedures), the need for reference materials, and the lack of trustworthy methods (validated methodologies barely exist today); but the regulatory issues also present great significance. Thus, there is not a widely acknowledged international regulatory framework for food safety that would standardize the management of risks associated with the use and application of such nanotechnology in the food field [114]. Most likely, EU has one of the most restrictive legislations in this respect, with regulations that implicitly/explicitly or either partially/fully address the standardization of NOMs in food. Such are the cases of Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) 2283/2015, 1332/2008, 1925/2006, 609/2013, 1924/2006 regulations, the directive 2002/46/CE (food supplements), and the “Guide to assess the risk about the application of nanoscience and nanotechnology in food and in the food chain” [Scientific Committee European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), 2011] [115–117].

It is obvious that incorporation of NOMs to food is an impressive way to enhance the bioavailability and bioaccessibility of food containing nutraceuticals. However, to know the nature, structure, properties, and risks associated with the implementation of these delivery systems is critical to consider the detection, identification, and characterization of these NOMs by using reliable and validated methodologies.

Regarding these NOMs analyses, it is an interesting task the discrimination between curcumin and nanocurcumin. Curcumin is a lipophilic bioactive compound with substantial health benefits due to its pharmacological actions and chemoprotective qualities for treating several diseases. It is characterized by its poor aqueous solubility that causes low bioavailability, high instability, or even degradation at basic aqueous media and under light radiation, limiting so its distinctive benefits. Food technology has achieved solutions to overcome such disadvantages by encapsulating curcumin. Currently, nanocurcumin is found in many nutritional supplements. However, these nanoformulations can be the object of significant doubts relative to food safety considerations due to the use of surfactants and other stabilizing chemicals also employed to prevent agglomeration and to hasten the delivery of their active ingredients. Unfortunately, few toxicological data about these nanosized curcumin formulations have been evaluated so far. Many of these nanosized particles are likely to display adverse effects owing to their small size and rapid diffusion through the entire body, specifically above a certain dosage, being of great concern the requirement of upcoming food sample stability studies and its associated nanotoxicological research. Thus, monitoring and quantifying the production and stabilization of such nanosized curcumin in food and supplementary matrices is crucial to ensure consumer safety. However, most of the research works reported so far have been just focused on the determination of free curcumin in different kinds of samples whereas only a few works have approached the detection of diverse curcumin nanoformulations, but their quantification always involved the breakup of curcumin-containing nanosystems, altering so its native nanostructure. Thus, it has been recently reported the quantification and discrimination of nanocurcumin (via micelle encapsulation) from free curcumin using a selective fluorescent probe based on graphene quantum dots (QDs) [118]. The presence of both analytes produces a gradual quenching in the emission response of the nanosensor; however, the presence of free curcumin causes a red shifting in the maximum wavelength of the graphene NPs response while the presence of nanocurcumin keeps it constant. This difference allows the determination and discrimination of both compounds in different types of food samples.

Another illustrative example lies in the antioxidant quercetin, which is a natural phenolic bioactive mostly found in fruits and vegetables among others. Furthermore, its intake is associated with numerous beneficial therapeutic effects against a wide range of illnesses. However, two factors prevent its therapeutic activity exclusively through diet: (1) food preparation and processing, since the quercetin concentrations considerably drop or perhaps entirely disappear; and (2) its lipophilic nature, which origins low bioavailability in the body. To overcome these limitations, quercetin dietary supplements were manufactured in the food industry. Thus, a nanometric carrier nanoemulsions-based has been recently developed to encapsulate it. Hence the helpfulness to propose analytical strategies for the discrimination between quercetin and nanoencapsulated quercetin. With this aim, it has been designed a liquid-state quantitative surface enhanced raman spectroscopy (SERS) sensing platform for the identification and quantification of Q-NEs using Au NPs like plasmonic arrays [119]. The differences in the Raman spectra for free and encapsulated quercetin allow its easy discrimination, with good sensitivity.

Conclusions

A critical overview, perspectives, and current challenges

In the last few years, it has been evidenced an increasing trend regarding the use of NMs in almost fields of human activity, the food area within them, where they can be applied to improve nutritional aspects for a wide variety of bioactive compounds, for instance allowing nanoencapsulations or enabling the building of nanocarriers for an improved bioavailability in humans, besides of potentially enhancing organoleptic properties too. Notwithstanding it, their meaningful usefulness must be balanced versus those aspects related to their potential toxicity (food safety) or environmental damages. In practice, more resources must be devoted to safety studies of NMs used in the food industry. Hence, the need for reliable analytical methodologies for their proper control. Thus, this issue must be recognized nowadays as a significant scientific challenge since the analysis of samples containing NMs is still at the very beginning infancy. Now, the traditional nanometrology already implemented for the characterization must be accordingly broadened to a wider concept including the detection and determination (if applicable) of NMs in diverse kinds of samples. ANM plays this role [94], which should undergo strong development in the upcoming years to provide food-control laboratories with suitable analytical tools to reliably carry out these pioneering analyses.

However, current ANM clearly shows bottlenecks with regard to their usefulness to end users (routine/control analytical laboratories). Thus, in a summarized way, the following problems can be today identified:

(1) Detection of real problems (situations), where nano-components may be found in specific samples. In this context, the connection to regulatory agencies and their corresponding legal framework becomes critical to evaluate potential risk assessment. Concerning this point, it should be highlighted there is not a single international regulatory framework to standardize the management of risks related to the application of nanotechnology in the field of food [114]. In fact, the country-specific legislation differs, but a similar general approach in terms of information requirements and approval procedures exists for all major world political and economic areas. Nevertheless, EU presents one of the most restrictive regulations in these terms. From the specific consulted literature [35, 113], four outstanding issues should be highlighted: a) NMs definition, b) the novel Foods regulation, c) the food/supplements authorization to commercialization processes, and d) the nanolabeling requirements.

(2) Sampling treatments must assure the integrity of the nano-analytes. One of the problems to measure NMs in food or in any other biological samples lies in the separation or pre-treatment (sampling) processes to which the sample (due to its heterogeneous nature) must be subjected, with the aim to separate the nanoanalyte under study from the interfering compounds of the matrix. Besides, due to the high reactivity they present, during these processes, the NMs can undergo changes either in their composition and/or in the particle size depending on the different media it faces, and not reflecting then their initial state in the sample therefore [120]. This is the reason why identifying those analytical strategies requiring less destructive or transformative sampling techniques is so important, since this is a meaningful problem not resolved yet.

(3) It will be of added value to promote the development of screening analytical methods for a rapid response. In this regard, it should stand out the recent development of pioneering sensing strategies based on non-destructive techniques, where the native nanostructure of the nano analytes under study is not altered along the full analytical process, supplying so proper information about their original physic-chemical properties. For instance, we are talking about some traditional spectroscopies, now adapted to NMs application, and generically renewed as surface enhanced spectroscopies, such as SERS, surface enhanced infrared spectroscopy (SEIR), and surface enhanced fluorescence (SEF) among others [60, 118, 119]. On the other hand, as Table 2 also evidences, attention should be paid to microfluidic technologies, which have emerged as a powerful tool because of their associated advantages such as cost-effectiveness in terms of low reagent consumption, fast analysis, and high portability. Thus, the combination of NMs with microfluidics provides improved nano-sensing devices for a wide number of detection strategies such as optical, electrical, magnetic, and acoustic according to the integrated techniques [64, 121], being also reported controlled microfluidic-based NMs synthesis on the literature [122, 123]. So far, these pioneering technologies have been mainly focused on bioanalysis and biomedical applications [65–67], although it is expected their quick growth in other prominent areas such as food science.

(4) Reliable standards are urgently required, for both calibration and validation of NMs analytical methodologies; and especially, the development of certified and standardized reference materials (matrix type), becomes critical to deepen this research field. Concerning this item, although there are already well-established techniques and analytical methodologies to detect and quantify inorganic NPs, this is not the case for organic NPs composed of polymers, lipids, and polysaccharides. Therefore, there is a clear need to develop and validate routine analytical methods to characterize NOMs, from their reproducible synthesis (certified standards) to their accurate quantification [124].

(5) Need for quality assurance schemes for the validation of NMs analytical methodologies: in this sense, the establishment of internationally validated and harmonized analytical methodologies is a pivotal stage in conducting to have a common international acceptance data framework; besides it is also a main exigency for the regulatory safety assessment, since it will allow controlling those analytical performance parameters that any reliable analytical methodology should satisfy [124].

Finally, it is worth noting from an analytical standpoint, the analysis of inorganic and organic NMs commonly needs different strategies. In fact, as already mentioned, ANM for inorganic NMs is more advanced, especially thanks to techniques such as ICP-MS and sp-ICP-MS, in some cases coupled with instrumental separation techniques [76, 125]. ANM for organic NMs is less established, and here the role of instrumental separation techniques (liquid chromatography, CE, and FFF) coupled to specific mass spectrometry (MS) and MS-MS detection will play a decisive task.

Thus, as Table 2 also displays, it must be aware of recent attentiveness towards techniques mainly based on size separation criteria such as SEC, HDC, and FFF (diverse modes of FFF) among others; these ones are already known, but currently, they are adapting to address the separation and even quantification of NMs [36, 113, 114, 120, 126]. Thus, they can offer outstanding features in terms of information about size, size distribution, ions release, NMs nature, and concentration [94].

For instance, FFF has become a very instructive and useful tool for characterising/determining NMs with minimal disturbances regarding original sample conditions. NMs separations are here related to their hydrodynamic behaviour under a specific applied field (with distinctive nature), which expands the versatility and applicability of this technique [75, 77, 87] thanks to the potential different FFF modes, although the dominant FFF one is the AF4 coupled to different detectors such as UV-Vis, ICP-MS, sp-ICP-MS, etc. Very illustrative examples are determinations of Ag NPs in chicken meat [78], tap and domestic water [79], nutraceuticals and beverages [80] and food simulants [110], which become highly revealing about its potential for the NMs analysis inside the alimentary/environmental fields. Interesting issues are also the determination of other NMs such as TiO2 NPs [77, 87], Pt NPs [76] in waters from different natures, which depicts troublesome scenarios of current importance.

Regarding chromatographic techniques, HDC has been scarcely applied for NMs determination so far, in spite to achieve analytical separations following a hydrodynamic radius criterion, which likely reflects in a realistic way one of the most checked aspects when information about NMs is asked. Some interesting examples with closer scopes to the studied topic can be the analytical characterization of Ag NPs in river waters [81, 82] or the size-separation, quantification, and chemical characterization of three different liposome-type NPs (NOMs) dispersed in a beverage matrix [83].

SEC has been also explored for the analytical characterization of different noble metal NPs and QDs [75, 84, 85]. As the physic-chemical properties of NPs and QDs responsible for quantum and surface effects are size dependent, the use of a size-separation technique seems to be quite suitable to obtain narrow-distribution NPs populations. On the other hand, information about the size distributions and optical properties of NPs can be obtained by coupling SEC with diverse detection modes such as UV-Vis and/or fluorescence spectroscopy [85]. Besides, there have been also reported very interesting applications like the characterization of a NOM (lipidic NPs) in terms of its mass distribution and polydispersity [86].

Abbreviations

| ANM: |

analytical nanometrology |

| CE: |

capillary electrophoresis |

| CLSM: |

confocal laser scanning microscopy |

| ENMs: |

engineered nanomaterials |

| EU: |

European Union |

| FFF: |

field flow fractionation |

| HDC: |

hydrodynamic chromatography |

| ICP-MS: |

inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry |

| NMs: |

nanomaterials |

| NOMs: |

nanostructured organic materials |

| NP: |

nanoparticle |

| QDs: |

quantum dots |

| Q-NEs: |

quercetin nanoemulsions |

| ROS: |

reactive oxygen species |

| SEC: |

size exclusion chromatography |

| sp-ICP-MS: |

single particle inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry |

| TEM: |

transmission electron microscopy |

| UV-Vis: |

ultraviolet-visible |

Declarations

Author contributions

NV: Investigation, Data curation, Visualization, Writing––original draft. MJV: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Writing––review & editing. ÁR: Conceptualization, Resources, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing––review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

The work is funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (MICINN) Grants [PID2019-104381GB-I00]; Regional Government of Castilla-La Mancha (JCCM) Grants [SBPLY/17/180501/000188].

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2023.