Abstract

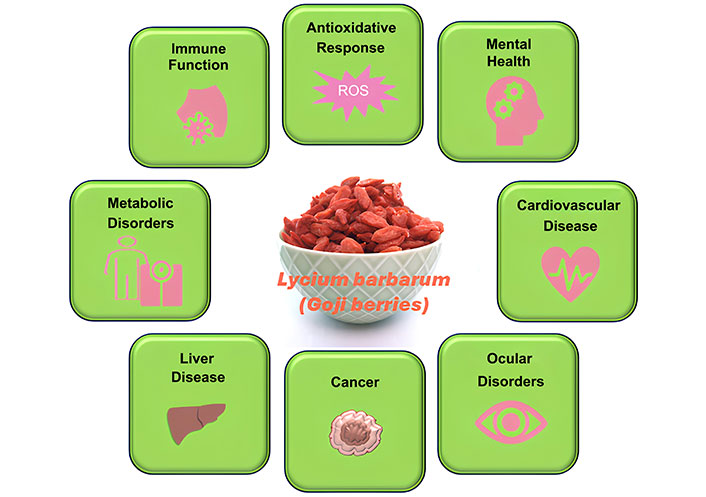

Native to East Asia and predominantly cultivated in regions such as the Ningxia Hui and Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Regions of China, Lycium barbarum (L. barbarum), commonly known as goji berry, has a long history in traditional medicine and is gaining recognition in contemporary health research. This review provides a comprehensive exploration of its botanical characteristics, pharmacokinetics, and safety, alongside a critical evaluation of human clinical studies investigating its therapeutic potential. Key health benefits include immune modulation, antioxidative effects, mental health support, ocular health preservation, and metabolic and cardiovascular regulation. Furthermore, its role in addressing age-related macular degeneration and chronic conditions such as cancer and metabolic syndrome is highlighted. The bioactivity of L. barbarum is attributed to its rich composition of polysaccharides, carotenoids, flavonoids, and other bioactive compounds, which exhibit anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, and metabolic-regulating properties. This review also examines the safety profile of L. barbarum, considering its side effects, toxicity, potential contamination, and interactions with medications, emphasising the importance of balancing its health-promoting properties with cautious consumption. Despite promising findings, gaps in the evidence base, including the need for larger, long-term, and rigorously controlled trials, remain significant barriers to clinical translation. By integrating traditional medicinal knowledge with modern scientific insights, this review underscores L. barbarum’s potential as a functional food and therapeutic agent. Its unique pharmacological properties and broad applicability position it as a valuable tool for health promotion and disease prevention, while highlighting areas requiring further research to optimise its safe and effective use.

Keywords

Lycium barbarum, goji berry, traditional Chinese medicine, health, functional food, human studies, pharmacokinetics, safetyIntroduction

The genus Lycium, comprising 97 species globally, of which 31 species purposed in food and medicine applications, belongs to the Solanaceae family, which also includes well-known crops like potatoes, tomatoes, peppers, and eggplants [1]. Among these species, Lycium barbarum (L. barbarum), Lycium chinense (L. chinense), and Lycium ruthenicum (L. ruthenicum) are particularly valued for their medicinal properties and functional food applications [2]. L. barbarum, commonly known as goji, is a deciduous woody shrub that is often characterised by its thorny branches. Predominantly found in East Asia, particularly in South China, Korea, and Japan, this species has been cultivated for over 600 years. Today, L. barbarum accounts for nearly 90% of the goji berries in the market [3]. Its fruits are highly valued for their rich nutritional content and numerous health benefits. L. barbarum is highly valued for its rich composition of micro- and macronutrients with notable biological activities. It is abundant in bioactive compounds such as polysaccharides, polyphenols, carotenoids, and dietary fibres, while also containing significant amounts of essential vitamins (e.g., thiamine, nicotinic acid, and riboflavin) and minerals (e.g., manganese, copper, magnesium, and selenium). These constituents contribute to the recognised health-promoting properties of L. barbarum [4]. Moreover, studies have shown that goji fruits contain essential mineral nutrients that exceeding 15% of the recommended daily allowances set by the Food and Nutrition Board (FNB). This nutrient profile highlights their potential as functional ingredients for use in diverse food and pharmaceutical formulations [5].

Botanical profile

The botanical name L. barbarum was first assigned by the botanist Carolus Linnaeus in 1753 [6]. The fruits of L. barbarum, commonly known as Ningxia goji berry or wolfberry, have gained global recognition as a “superfood” due to their rich nutritional value. Various parts of the plant, including the root, fruit, and leaf, have been utilised in traditional medicine for their health-promoting properties [7].

L. barbarum and L. chinense are closely related species, both commonly referred to as red goji or red wolfberry. However, L. barbarum is particularly known for producing larger and sweeter fruits, while L. ruthenicum, or black goji, is distinguished by its dark-coloured berries [8], which derive their deep hue from anthocyanins, potent antioxidants, associated with various health benefits [9]. These berries are also rich in a branched arabinogalactan protein, which further enhances their antioxidant properties and therapeutic potential [10]. The fruits of L. barbarum are red or orange-yellow, oblong in shape, and contain between 4 to 20 seeds. The plant’s flowers feature a 1–2 cm pedicel, a 4–5 mm campanulate calyx, typically 2-lobed, and a corolla tube 8–10 mm in length. L. barbarum can grow to a height of 0.8–2 m, with thorny branches and lanceolate or long elliptic leaves that are grey-green, ranging in diameter from 25–50 mm [11–13].

The historical use of L. barbarum dates back over 4,000 years, with its earliest mention in the ancient text “Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing” (The Classic of Herbal Medicine), written between 200 and 250 AD. Since the early 20th century, the plant has been commonly referred to as goji, derived from the Chinese term “Gou Qi” [13]. Classified under the division Magnoliophyta, class Magnoliopsida, and family Solanaceae, L. barbarum is also known by several traditional vernacular names, including boxthorn, Chinese wolfberry, and matrimony vine, especially when referring to L. barbarum or L. chinense [14, 15].

Geographic distribution

China is the largest producer of goji berries worldwide, accounting for approximately 95,000 tonnes annually, with L. barbarum being the most widely cultivated variety. The majority of these plantations are located in the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region and the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region [16]. Other varieties, such as L. chinense, are also cultivated and distributed across East Asia, including South China, Korea, and Japan [17]. While Asian countries dominate global production, the exact origin of L. barbarum remains uncertain. It is, however, believed to have originated around the Mediterranean basin [8].

Ecology

L. barbarum thrives in soils with an optimal pH range of 6.8 to 8.1 [18]. Although it is cultivated in arid to semi-arid regions across the world, including Africa, North and South America, and Eurasia [19], the plant favours moderately moist conditions and well-drained soils. Environmental factors such as rainfall, temperature, and soil salinity significantly influence the plant’s chemical composition and the concentration of its bioactive compounds [20, 21]. The harvesting season for L. barbarum typically spans from late summer to autumn. After harvesting, the fruits are initially dried in shaded areas until their skin begins to shrink. Then they are exposed to sunlight until the outer skin fully dries and hardens [11, 22].

Historical and traditional uses

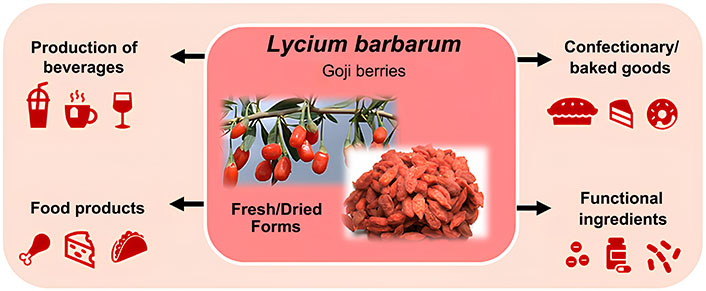

Traditionally, various parts of Lycium plants, including the fruit, leaves, young shoots, and root bark, have been utilised for both medicinal and functional food purposes [22]. In traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), these plants have been credited with beneficial effects on a range of conditions and diseases, such as diabetes, asthma, and nervous fatigue, and are believed to enhance vision and nourish vital organs like the liver and kidneys [1, 23]. As a food source, L. barbarum berries are commonly consumed in dried form or incorporated into various food products, such as yogurt, tea, and granola [24].

Methodological design

The methodology used to formulate this article included reviewing published reports from various databases (from inception to 03 June 2024, without language restrictions): Scopus, PubMed, Google Scholar, ISI Web of Science, and CNKI to maximise the retrieval of relevant results. We considered both review and original research articles involving L. barbarum studies. The search keywords for screening the literature information were: “Lycium barbarum”, “L. barbarum”, or “goji berries” in combination with “health”, “diseases”, and “safety”. The database search was supplemented by consulting the bibliography of the articles, reviews, and published meta-analyses. The literature research was not limited to a time period, but a particular focus was given to the studies from the past 20 years. Relevant articles were chosen after reviewing all titles and abstracts. Full texts were further examined if the information contained in the title or abstract was insufficient to exclude the study. The Figures included in this review were created using Microsoft PowerPoint. Icons and photos were sourced from the authors’ own collection, Microsoft, and Wikimedia Commons. Specifically, one image in Figure 2 was obtained from Wikimedia Commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lycium_barbarum_-_Wolfberries_on_vine.jpg), which is in the public domain.

Pharmacokinetics

In the pharmacological landscape, the complex composition of L. barbarum has garnered attention due to their diverse therapeutic applications, particularly influenced by their pharmacokinetic profiles. The recent findings provide an in-depth perspective on the exploration of the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) processes taken place due to primary constituents present in L. barbarum berries, mainly L. barbarum polysaccharides (LBPs), polyphenols, carotenoids, tropane alkaloids, and others. Studies showed that the adsorption kinetics of LBPs found in L. barbarum berries significantly dictate their efficacy, being transported via the bloodstream to various tissues [25]. For example, fluorescein isothiocyanate labelling was used to quantify the levels of LBPs in in vivo models, showing moderate bioavailability in different organs [25–27]. Upon ingestion, polysaccharides undergo partial enzymatic hydrolysis in the gastrointestinal tract, rapidly converting into lower molecular weight sugars that can be absorbed. For instance, levels of LBPs labelled with fluorescein isothiocyanate were detected in the small intestine (121.78 µg/g), stomach (76.53 µg/g), liver (26.01 µg/g), and kidney (10.57 µg/g) within one hour following oral administration [26]. After 6 h, polysaccharide concentrations increased in the kidney (83.1 µg/g), large intestine (43.34 µg/g), and liver (29.97 µg/g); while decreasing in the small intestine (13.17 µg/g) and stomach (31.50 µg/g) compared to the one-hour measurements [26]. The increased concentration of LBPs reached its peak after 24 h of administration, primarily identified in the liver. Similarly to the previous study [28], this suggests a higher preference for the liver, and the detrimental effect on the kidney could be related to the larger pore size of the capillary wall of the mice’s kidney [26].

A pharmacokinetic tracking study reported that LBPs are not easily absorbed in the body and are slowly eliminated through urine and faeces, with a cumulative excretion rate of 92.27% within 72 h after 50 mg/kg LBPs intake [27], thus indicating a longer stagnation in the large intestine.

Carotenoids such as zeaxanthin and β-carotene [29] are absorbed in the small intestine. Their lipophilic nature would require the presence of dietary fats in the small intestine for effective absorption, as they are incorporated into micelles made from dietary lipids and bile acids [30]. Hempel et al. [31] demonstrated that the addition of coconut lipids (1%) boosted the release of zeaxanthin from L. barbarum berries by 89% compared to intake without fats in an in vitro digestion model. Whereas LBPs would prefer immune-related organs, in contrast, carotenoids were predominantly distributed to the liver and eyes [31]. The high affinity of zeaxanthin for the macular region is particularly notable, as it is critical in filtering harmful high-energy blue light and quenching free radicals [31]. Carotenoids undergo oxidative cleavage by the enzyme carotenoid dioxygenase, producing vitamin A and other smaller metabolites that play essential roles in vision, growth, and immune function [32]. Notably, when ingested, zeaxanthin is minimally metabolised, which might explain its significant accumulation in fatty tissues, but more predominantly in the macula [11].

Excretion patterns of L. barbarum bioactive compounds vary, with LBPs primarily excreted via the kidneys in their monosaccharide forms [11]. In contrast, carotenoids are mainly eliminated through faeces as part of the bile and exhibit a longer elimination time, which can take up to 7 days [32].

The detailed ADME characteristics of L. barbarum phytochemicals suggest their substantial roles in preventative and therapeutic health applications. Understanding these pharmacokinetic properties is essential for optimising dietary recommendations and therapeutic dosages, particularly in developing nutraceutical products aimed at enhancing immune function and protecting against oxidative stress-related diseases.

Human clinical studies

Recent human studies highlight the therapeutic potential of L. barbarum across a range of health conditions, including its role in immune support, antioxidant enhancement, mental health, and the management of ocular, metabolic, and cardiovascular disorders, as well as certain cancers and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). L. barbarum’s multifaceted health benefits are illustrated in Figure 1, demonstrating its impact on specific physiological processes associated with these conditions. Table 1 provides a summary of the clinical studies conducted to date, highlighting key outcomes and reinforcing L. barbarum’s promise as a functional food with diverse health applications.

Summary of clinical studies on the effects of Lycium barbarum (goji berry) supplementation on health conditions

| Conditions | Study design | Participant information | Key findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General well-being, neurologic/psychologic traits, gastrointestinal function | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 14 days duration | Healthy adults, 16 in the GoChi group, 18 in the control group |

| [33] |

| Immune function, general well-being | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 30 days intervention | 60 healthy older adults, aged 55–72 |

| [34] |

| Immune response, vaccine efficacy | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 3 months intervention | 150 healthy elderly, aged 65–70 |

| [35] |

| Immune response, vaccine efficacy, antioxidant properties | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 3 months duration | 150 healthy elderly adults, aged 65–70, community-dwelling Chinese population |

| [36] |

| General health (sleep, energy, TCM outcomes) | Double-blind, randomised controlled | 27 adults, 14 in the goji berry group (20 g/day), 13 in the control group (15.7 g green raisins/day) |

| [37] |

| Oxidant stress-related conditions | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 30 days duration | 50 healthy Chinese adults, aged 55–72, GoChi (120 mL/day) |

| [38] |

| Oxidative stress, age-related disorders | Parallel design, randomised controlled, 16 weeks duration | 40 middle-aged and older adults, 22 in the wolfberry group, 18 in the control group, 15 g dried wolfberry/day |

| [39] |

| Depression, inflammatory response | Double-blinded, randomised, placebo-controlled, 6 weeks duration | 29 adolescents with subthreshold depression, aged 14–16 |

| [40] |

| Subthreshold depression | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 29 adolescents with subthreshold depression (15.13 ± 2.17 years) |

| [41] |

| MDD | Double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, 6 weeks duration | 284 estimated participants, aged 18–60 years | Ongoing study | [42] |

| AMD | Randomised, unmasked, parallel-arm study, 90 days duration | 27 participants, aged 45–65, consuming either 28 g goji berries or a supplement (6 mg lutein and 4 mg zeaxanthin) five times weekly |

| [43] |

| AMD | Single-blinded, placebo-controlled, parallel design, 28 days duration | 27 healthy subjects (14 wolfberry group, 13 control), consuming 15 g wolfberry (3 mg zeaxanthin) daily |

| [44] |

| Macular health | Double-masked, randomised, placebo-controlled, 90 days duration | 150 healthy elderly subjects (65–70 years), 75 in the LWB group, 75 in the control group, supplemented daily with 13.7 g/day LWB or placebo |

| [45] |

| AMD | Randomised, single-blind, cross-over | 12 volunteers, administered either 5 mg of esterified or non-esterified 3R,3'R-zeaxanthin, suspended in yogurt with a balanced breakfast, with a 3-week depletion period between interventions |

| [46] |

| AMD | Double-blinded, controlled, human intervention, multiple cross-over design, 3–5 weeks washout period | 12 healthy, consenting subjects, aged 21–30, administered a zeaxanthin-standardised dose (15 mg) from three wolfberry formulations (hot water, warm skimmed milk, and hot skimmed milk) in randomised order |

| [47] |

| RP | Double-masked, placebo-controlled | 42 RP patients (23 in the treatment, 19 in the control group) receiving daily L. barbarum or placebo granules for 12 months |

| [48] |

| Mild hypercholesterolemia, overweight | Randomised, double-blind, parallel groups, 8 weeks duration | 53 overweight and hypercholesterolemic subjects, 26 in the WBE group, 27 in the placebo group, consuming 13.5 g WBE or placebo daily |

| [49] |

| Body weight, central adiposity | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multiple-period crossover design | 8 adult subjects (age 45 ± 5 years) with varying doses of dietary fibre (0 g, 1 g, 5 g, 10 g) and 15 mL of L. barbarum juice |

| [50] |

| Weight loss, waist circumference | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 14 days intervention | 15 healthy adults (aged 34 years, BMI = 29 kg/m2), multiple doses of L. barbarum |

| [51] |

| Obesity prevention, metabolism | Randomised, double-blind, crossover | 17 healthy overweight males, aged 18–65 |

| [52] |

| Metabolomics, lipid metabolism | Randomised controlled, 4 weeks duration | 42 healthy male adults, LBP supplementation (300 mg/day) |

| [53] |

| Type 2 diabetes | Randomised controlled, double-blind | 67 type 2 diabetes patients, 37 in the LBP group, 30 in the control group |

| [54] |

| Cardiovascular health | Parallel design, randomised controlled | 40 Singaporean adults, aged 50–64 |

| [55] |

| Cardiovascular health | Randomised, parallel design, 16 weeks duration | 41 middle-aged and older adults |

| [56] |

| Immune function, antioxidant activity | Randomised controlled, 6 weeks duration | 46 male taekwondo athletes, aged 18–22, 23 per group |

| [57] |

| MS, cardiovascular health | Randomised controlled, parallel design, 45 days duration | 50 MS patients, 15 males, 35 females |

| [58] |

| Atherosclerosis, cardiovascular health | Controlled trial comparing LBP and Qigong exercise, 3 months duration | Elderly male participants, administered LBP or engaged in Qigong exercise |

| [59] |

| Cardiovascular health | 16-week intervention with HDP with or without wolfberries | 24 middle-aged and older adults, 9 in the HDP group, 15 in the HDP + wolfberry group |

| [60] |

| Advanced cancer (multiple types) | Clinical trial with LAK/IL-2 + LBP combination | 79 advanced cancer patients, 75 evaluable (malignant melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, colorectal carcinoma, lung cancer, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, malignant hydrothorax) |

| [61] |

| NAFLD | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 50 NAFLD patients | Ongoing trial | [62] |

AMCAT: Agarose Microscopy-based Cell Assay Technology; AMD: age-related macular degeneration; BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition; BMI: body mass index; BOEC: blood outgrowth endothelial cell; CAT: catalase; CVD: cardiovascular disease; ffERG: full-field electroretinography; GSH-Px: glutathione peroxidase; HAMD: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; HDL: high-density lipoprotein; HDP: healthy dietary pattern; IgG: immunoglobulin G; IL: interleukin; Kessler: Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10); LAK: lymphokine-activated killer; LBP: Lycium barbarum polysaccharide; L. barbarum: Lycium barbarum; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; LWB: Lacto-Wolfberry; MDA: malondialdehyde; MDD: major depressive disorder; MPOD: macular pigment optical density; MS: metabolic syndrome; NAFLD: non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; NK: natural killer; PPEE: postprandial energy expenditure; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; RMR: resting metabolic rate; RP: retinitis pigmentosa; SCARED: Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders; SOD: superoxide dismutase; TCM: traditional Chinese medicine; TG: triglyceride; WBE: aqueous extract of wolfberry fruit

Immune support

Numerous studies have provided evidence of the positive effects of L. barbarum on general health and well-being, particularly when consumed as juice. For example, Amagase and Nance [33] found that standardised L. barbarum juice (GoChi) significantly improved participants’ overall health. In this pioneering study outside of China, participants who consumed 120 mL/day of GoChi (equivalent to approximately 150 g of fresh L. barbarum fruits) for 14 days exhibited enhanced well-being, improved neurological function, and better gastrointestinal health.

Building on these findings, a meta-analysis by Amagase and Hsu [63] assessed the effects of daily GoChi consumption in 161 participants aged 18–72. This study revealed significant improvements in mental acuity, sleep quality, reduced stress, and enhanced focus and energy levels. In a separate randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial involving older adults (aged 55–72), Amagase et al. [34] reported that 120 mL/day of L. barbarum juice for 30 days significantly boosted immune function. Participants exhibited higher lymphocyte counts and increased levels of interleukin (IL)-2 and immunoglobulin G (IgG), while no significant changes were observed in IL-4 and IgA. Importantly, no adverse reactions were reported, indicating the safety of L. barbarum juice in enhancing immune response. In a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, Lacto-Wolfberry (LWB) supplementation over three months in elderly individuals enhanced immune response to the influenza vaccine, demonstrating significantly higher post-vaccination serum influenza-specific IgG levels compared to placebo, without serious adverse effects [35].

In another supportive study, Vidal et al. [36] assessed the effects of long-term dietary supplementation with a milk-based wolfberry preparation in 150 elderly participants (aged 65–70). The study demonstrated that consuming 13.7 g/day of LWB resulted in a higher IgG-specific antibody response, greater seroconversion, and enhanced protection following influenza vaccination compared to a placebo group. Additionally, this supplementation was associated with a lower incidence of macular hypopigmentation and soft drusen, suggesting a potential protective effect against age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

However, contrasting findings have emerged in which the study published by Gonçalves et al. [37] investigated the consumption of 20 g/day of dried L. barbarum fruit in a randomised controlled trial. The study found no significant differences between the L. barbarum group and a control group consuming 15.7 g/day of raisins, in terms of waist circumference, systolic and diastolic blood pressure. The authors speculated that these results might have been influenced by unmeasured external factors, or that raisins and L. barbarum may share similar bioactive properties. This suggests that the potential health benefits of dried L. barbarum may not be as pronounced as those seen with fresh juice or other preparations.

Antioxidant enhancement

In another investigation by Amagase et al. [38], the antioxidant effects of LBPs in GoChi juice were evaluated through a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial involving 50 healthy adults aged 55–72. Participants consumed 60 mL of GoChi twice daily for 30 days. Significant increases were observed in several antioxidant markers, including an 8.4% rise in superoxide dismutase (SOD), a 9.9% increase in glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), and an 8.7% elevation in malondialdehyde (MDA) levels. These findings suggest that GoChi enhances the body’s endogenous antioxidant defences, which may help prevent free radical-related conditions such as neurodegenerative diseases, cardiovascular disorders, and cancers [64].

However, the authors acknowledged several limitations, including the inadequacy of the antioxidant markers employed and a limited understanding of the bioavailability and bioactivity of the active compounds in LBPs. A longer study period is also recommended to confirm whether these benefits are sustained and clinically relevant in disease prevention [38].

Further supporting the antioxidant potential of L. barbarum, a study by Toh et al. [39] explored its effects on reducing oxidative stress in middle-aged and older adults. In this 16-week randomised controlled trial, 40 participants aged 50–64 consumed 15 g of L. barbarum daily. Significant increases were observed in plasma levels of 8-iso-prostaglandin F2α, zeaxanthin, and skin carotenoids in the test group, compared to the control group, which showed no changes. This study aligns with previous findings and highlights L. barbarum’s potential in reducing oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation, especially when consumed alongside a healthy diet [38].

Mental health

LBPs have also shown promise in improving mental health, particularly in alleviating symptoms of depression. Depression, or major depressive disorder (MDD), is currently ranked third in the global burden of disease by the World Health Organisation and is projected to become the leading cause by 2030 [65]. Subthreshold depression (StD), characterised by depressive symptoms that do not fully meet MDD criteria, is also associated with impaired social functioning [66].

Li et al. [40] investigated the effects of LBPs on StD through an anti-inflammatory mechanism. In a six-week trial involving 29 adolescents, the study demonstrated a significant reduction in depressive symptoms in the LBPs group compared to the placebo group. This reduction was associated with decreased IL-17A levels and attenuated connectivity between inflammatory factors. These findings suggest that LBPs may alleviate depressive symptoms by modulating inflammation.

Further evidence from another study by Li et al. [41] supports the efficacy of LBPs in managing StD. In this randomised, placebo-controlled trial, adolescents receiving 300 mg/day of LBPs exhibited greater reductions in Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD) scores and higher remission rates than the placebo group. However, the authors emphasised the need for larger sample sizes to corroborate these promising results. Additionally, an ongoing clinical trial (NCT04124276) is investigating the effects of LBPs on patients with MDD. This trial may provide further insights into the mental health benefits of L. barbarum and help solidify its role in managing depressive disorders [42].

Ocular health management

Clinical studies have highlighted the potential benefits of L. barbarum for eye health, particularly in the prevention and management of ocular disorders such as AMD and retinitis pigmentosa (RP).

A study by Li et al. [43] demonstrated that daily consumption of 28 g of L. barbarum berries for 90 days significantly increased macular pigment optical density (MPOD) in healthy middle-aged adults. This randomised trial involved 27 participants aged 45–65 who consumed either L. barbarum berries or a supplement containing 6 mg of lutein and 4 mg of zeaxanthin five times a week for three months. Notably, the L. barbarum group exhibited significant increases in MPOD at 0.25 and 1.75 retinal eccentricities, while the supplement group showed no changes. As low MPOD levels are associated with a higher risk of AMD [67], these findings suggest that L. barbarum berry consumption may offer protection against AMD. However, further research is required to confirm these effects and explore the long-term benefits.

Supporting these results, Cheng et al. [44] conducted a single-blind, placebo-controlled trial examining the effects of short-term supplementation with 15 g of L. barbarum berries. The study found a 2.5-fold increase in fasting plasma zeaxanthin levels post-supplementation, which has been linked to a reduced risk of late AMD [68]. Further evidence of L. barbarum’s ocular benefits comes from a double-masked, randomised, placebo-controlled trial, which assessed the effects of a proprietary goji berry formulation, LWB, on macular health. The study involved 150 elderly individuals aged 65–70 years. Participants consuming LWB for 90 days exhibited stable macular pigmentation and a significant reduction in soft drusen accumulation, alongside a 26% increase in plasma zeaxanthin levels and a 57% rise in total antioxidant capacity compared to the placebo group [45]. These findings suggest that goji berry supplementation may play a role in preserving macular integrity and overall eye health in ageing populations, although the precise mechanisms require further exploration.

The bioavailability of zeaxanthin from L. barbarum has also garnered research attention. Breithaupt et al. [46] conducted a randomised, single-blind, crossover study with 12 participants, comparing the absorption of 5 mg of non-esterified versus esterified 3R,3'R-zeaxanthin palmitate, both administered in yogurt. The results indicated that the esterified form had enhanced bioavailability, with peak concentrations occurring between 9–24 h. This emphasises the significance of the zeaxanthin formulation consumed, though further studies are required to better understand the mechanisms behind the enhanced absorption. Benzie et al. [47] expanded these findings by investigating the bioavailability of zeaxanthin from different L. barbarum berry formulations in a double-blinded, controlled human intervention trial. In this study, 12 participants consumed a zeaxanthin-standardised dose (15 mg) with a standardised breakfast. The results revealed that homogenising the berries in hot skimmed milk significantly improved zeaxanthin bioavailability, with a threefold increase compared to other methods. This outcome is particularly relevant for maintaining macular pigment and reducing the risk of AMD, highlighting the importance of optimising zeaxanthin delivery methods. A randomised cross-over study comparing the bioavailability of H- and J-aggregated zeaxanthin in 16 participants found that the J-aggregated form had 23% higher postprandial bioavailability than the H-aggregated form, although the difference was marginally significant. This suggests that aggregation forms influence carotenoid absorption, with implications for eye health [69]. Long-term supplementation trials are needed to assess the efficacy of enhanced bioavailability of zeaxanthin supplements in maintaining macular pigment density and preventing AMD [70]. Beyond AMD, L. barbarum has also shown promise in managing other eye-related diseases, such as RP. A study by Chan et al. [48] involving 42 RP patients over 12 months, found that daily L. barbarum supplementation helped preserve visual acuity and macular structure, suggesting a neuroprotective effect that may delay or minimise cone degeneration in RP patients. Another double-masked, randomised clinical trial evaluated L. barbarum treatment in retinitis RP patients, showing that six months of L. barbarum supplementation led to a modest improvement in low-contrast visual acuity and central visual sensitivity, indicating a potential neuroprotective effect on retinal function [71].

In summary, clinical studies indicate that L. barbarum may offer significant benefits for eye health, particularly in increasing MPOD, enhancing zeaxanthin bioavailability, and potentially protecting against AMD and RP. However, further research, including long-term clinical trials, is necessary to fully validate these findings and understand the mechanisms involved.

Metabolic disorders

Human trials have examined the effects of L. barbarum on various metabolic disorders, including obesity, metabolic syndrome (MS), type 2 diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia—all of which impact metabolism [72].

One such study by Lee et al. [49], a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, involved 53 overweight and hypercholesterolemic subjects who were administered 13.5 g of L. barbarum extract over eight weeks. The trial demonstrated that L. barbarum exhibited antioxidative and anti-inflammatory effects, primarily through the modulation of mRNA expression levels, suggesting its potential to positively impact metabolic disorders.

Further supporting this, Amagase and Nance [50] conducted a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with a multiple-period crossover design to evaluate L. barbarum’s impact on metabolic rate and body weight. The participants received varying doses of dietary dextrin (0, 1, 5, and 10 g) combined with low doses of L. barbarum juice (GoChi). The results indicated a significant increase in resting metabolic rate (RMR), with a 7.2% to 8.4% rise from baseline within 4 h post-intake. This suggests that L. barbarum, particularly in combination with indigestible dietary fibre, can enhance metabolic rate.

In a related study, Amagase and Nance [51] also explored the effects of L. barbarum juice on RMR and postprandial energy expenditure (PPEE). Participants received single bolus doses of 30 mL, 60 mL, and 120 mL of L. barbarum juice. The study found a 10% increase in PPEE at 1 h post-intake for the highest dose (120 mL). Moreover, the waist circumference of the L. barbarum group reduced significantly by 5.5 cm ± 0.8 cm compared to pre-intervention measurements, while the placebo group showed no significant change (0.9 cm ± 0.8 cm). These findings provide further evidence of L. barbarum’s beneficial effects on metabolic health.

In contrast, van den Driessche et al. [52] conducted a study with 17 healthy, overweight males and found no significant impact of L. barbarum on PPEE or substrate oxidation. Although energy expenditure increased after both L. barbarum and control meals, no differences were observed between the two groups. Moreover, L. barbarum did not affect lipid or glucose metabolism markers. The authors speculated that variations in participant characteristics, such as age or gender, might account for discrepancies between their findings and those of previous studies.

Exploring L. barbarum’s effects on a molecular level, Xia et al. [53] conducted a study integrating serum and urine metabolomics with phytochemical analysis in 42 young, healthy males. Participants received 300 mg/day of LBPs or a placebo for four weeks. The results indicated that LBP supplementation reduced the triglyceride/high-density lipoprotein (TG/HDL) ratio, a biomarker linked to cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk [73]. Lower TG/HDL ratios are associated with reduced cardiometabolic disorder risks [74]. The study also suggested that LBPs influence glycerophospholipid and tyrosine metabolism, although the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. Notably, the focus on healthy males may have limited the observation of significant biochemical changes, highlighting the need for further research in more diverse populations.

Given the rising global prevalence of obesity and its contribution to type 2 diabetes [75], the potential anti-diabetic effects of dietary supplements, including LBPs, have garnered increasing attention. Cai et al. [54] investigated the impact of LBP supplementation in 67 patients with type 2 diabetes. Participants were given capsules containing LBPs (150 mg) and microcrystalline cellulose (150 mg) twice daily for three months. The study demonstrated a significant reduction in serum glucose levels and an improvement in the insulinogenic index. Furthermore, LBP supplementation resulted in higher HDL cholesterol levels, a factor associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular events [76].

Cardiovascular disease

L. barbarum, abundant in antioxidants such as polysaccharides, flavonoids, and carotenoids, has been widely studied for its potential cardiovascular benefits, particularly due to its ability to reduce oxidative stress, a key factor in CVD [77]. In a 16-week randomised controlled trial, Toh et al. [55] investigated the effects of L. barbarum on cardiovascular health by administering 15 g of L. barbarum fruits daily. The results demonstrated improved adherence to a healthy dietary pattern (HDP) and enhanced blood lipid profiles, including significant improvements in HDL cholesterol. Additionally, there are reductions in long-term CVD risk and vascular age compared to the control group. While both groups showed enhanced vascular tone, wolfberry supplementation further improved blood lipid profiles, suggesting its potential cardiovascular benefits. Building on this, Toh et al. [56] extended their research to examine the impact of L. barbarum on plasma lipidome in middle-aged to older adults. Daily consumption of 15 g of wolfberry for 16 weeks led to notable alterations in the plasma lipidome, which likely contributed to the cardiovascular protective effects. These changes may also explain L. barbarum’s role in reducing oxidative damage, further supporting its use in cardiovascular health management.

Similarly, Ma et al. [57] evaluated the effects of LBPs on cardiovascular health in 18–22-year-old taekwondo athletes. Participants taking 0.36 mg of LBPs twice daily for six weeks exhibited improved physical performance, enhanced antioxidant capacity, and immune function. Moreover, the study showed reductions in MDA levels, a marker of lipid peroxidation, indicating decreased oxidative stress. Elevated levels of SOD and catalase (CAT) further supported the conclusion that L. barbarum reduces oxidative stress, benefiting cardiovascular health. In a randomised controlled trial by de Souza Zanchet et al. [58], 50 patients with MS consumed 14 g of L. barbarum daily for 45 consecutive days. Results indicated reductions in abdominal fat, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, waist circumference, and lipid peroxidation, highlighting L. barbarum’s potential as an effective dietary supplement for CVD prevention in MS patients.

Yu et al. [59] took a more holistic approach by assessing the combined effects of LBPs and Qigong exercise in elderly participants aged 52–73. Over three months, the participants who received LBPs (100 mg/kg body weight daily) or engaged in Qigong exercise experienced reductions in diastolic blood pressure and improvements in lipid profiles. The combination of LBPs and exercise was particularly effective in lowering long-term cardiovascular risk, suggesting that lifestyle factors may enhance the cardiovascular benefits of LBPs. Xia et al. [60] explored the effects of a HDP, with or without wolfberry supplementation (15 g/day for 16 weeks), on blood outgrowth endothelial cells (BOECs) in middle-aged and older adults. While the HDP alone significantly improved BOEC colony growth, angiogenic capacity, and migration activity, wolfberry supplementation did not offer additional benefits. Interestingly, positive correlations were found between BOEC colony numbers and cardiovascular risk factors, highlighting the importance of dietary modification in enhancing endothelial function and promoting cardiovascular health.

Cancer

Interest in the anti-cancer properties of L. barbarum has increased, although human studies remain limited. In a study by Cao et al. [61], LBPs were used as an adjuvant to lymphokine-activated killer (LAK) cells and IL-2 therapy in patients with various cancers, including malignant melanoma, lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma, and colorectal carcinoma. The combination therapy resulted in a 40.9% cancer regression rate, significantly higher than the 16.1% regression observed with LAK/IL-2 therapy alone (P < 0.05). Additionally, LBPs enhanced natural killers (NKs) and LAK cell activity, indicating that LBPs may play a role in boosting the immune response against cancer cells.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

NAFLD has become the most prevalent chronic liver disease globally, with growing interest in therapies targeting the gut microbiota to manage the condition [78–80]. LBPs are being explored for their potential prebiotic effects, which may positively influence gut health and, consequently, NAFLD progression [81]. While clinical studies are still scarce, a notable ongoing trial (ChiCTR2000034740) by Gao et al. [62] is investigating the effects of LBP supplementation in NAFLD patients. This randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, involving 50 participants aged 45 to 59, aims to assess LBPs’ impact on NAFLD progression and gut microbiota characteristics. Although the results are not yet available, this research holds promise for establishing LBPs as a low-risk therapeutic option for NAFLD, advancing gut microbiota-targeted strategies for the disease’s management.

Side effects, toxicity, and safety

L. barbarum berries have been an integral part of Chinese traditional culture for centuries, valued both as herbal medicine and a dietary ingredient and are generally regarded as non-toxic [24]. However, as a member of the nightshade (Solanaceae) family, concerns have been raised regarding the potential presence of toxic compounds, such as tropane alkaloids (e.g., atropine) [82] and steroidal alkaloid glycosides (e.g., lyciosides A and B) [83]. Despite these principal concerns, research investigating the presence and impact of these compounds in L. barbarum remains limited. Tropane alkaloids, which are natural secondary metabolites found in various food plants, including those in the Lycium genus, appear to vary in concentration depending on the species [82]. For instance, the atropine level in L. barbarum fruits was reported at the detection limit (0.01 mg/kg), whereas fruits of L. europaeum showed atropine at significantly higher levels (0.59 mg/kg dry weight) [82]. In its assessment of L. barbarum as a food supplement, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) identified potential health concerns related to the presence of atropine and hyoscyamine in the fruit and peel [84]. While hyoscyamine was detected in the roots (0.25%), shoots (0.33%), and fruits (0.29%) of L. barbarum, the identified levels of atropine were considered too low to pose significant risk concern [84].

Further analysis supports the notion that L. barbarum may not accumulate these compounds at concerning levels. A study employing quantitative thin layer chromatography found no detectable levels of tropane alkaloids (e.g., L-hyoscyamine, scopolamine) or steroidal alkaloids (e.g., α-solanine, α-chaconine) in the fruits, leaves, stems, or roots of three L. barbarum varieties [85].

Research on zeaxanthin, another secondary metabolite and carotenoid known for its benefits to eye health, has consistently demonstrated its safety and lack of toxicity [32]. Subchronic toxicity studies in rats showed no adverse effects at doses as high as 400 mg/kg body weight per day [86]. Likewise, meso-zeaxanthin exhibited no toxicity in rats even at doses of up to 200 mg/kg per day [87]. Chronic studies in cynomolgus monkeys revealed no adverse events at a dose of 20 mg/kg per day [88], and high-dose supplementation in rhesus monkeys caused no ocular toxicity [89]. Genotoxicity testing using bacterial strains found no evidence of mutagenicity for either zeaxanthin or meso-zeaxanthin [86, 87]. Based on these findings, EFSA has established an acceptable daily intake of 53 mg/day for a 70 kg adult, with a recommended usage level of 2 mg/day approved by the EU Commission [88]. With great bioactive potential revealed by the LBPs presence in goji berries, excessive intake may lead to health-related issues, for which a balanced diet outweighing the risks given by LBPs from goji berries intake would be more appropriate.

Additionally, while the primary focus of this section is on the potential toxicity and safety concerns related to the metabolites of L. barbarum, it is also important to address the potential health risks associated with chemical contaminants, such as pesticides and toxic elements. Several studies have reported the presence of heavy metals in these superfruits, raising concerns about potential adverse effects on human health, particularly with long-term consumption or excessive intake. Zhang et al. [90] noticed an increased level of heavy metals (such as Pb, Cd, Cu, Zn, As) in L. barbarum samples collected from plantations in comparison with those from supermarkets, except for Ni, registering higher Ni content in samples collected from supermarkets (0.90 mg/kg ± 0.57 mg/kg). Similar trend was noticed regarding the presence of pesticides such as dichlorvos (0.02 mg/kg ± 0.03 mg/kg), omethoate (0.02 mg/kg ± 0.05 mg/kg), malathion (0.01 mg/kg ± 0.03 mg/kg), cypermethrin (0.02 mg/kg ± 0.03 mg/kg), and fenvalerate (0.88 mg/kg ± 0.70 mg/kg) in samples from plantations whereas such pesticides were not detected in those collected from supermarkets, except for dichlorvos (0.01 mg/kg ± 0.02 mg/kg) [90]. However, the levels of both pesticides and metals in analysed samples would not pose serious health risks associated with chronic exposure, as were considerably lower than the maximum residue limits [90]. Furthermore, the increased demand for L. barbarum berries is significantly influenced by the potential use of pesticides to prevent any pests and diseases that can potentially lead to a reduction in harvest and quality [91]. Therefore, the use of pesticides in foods is constantly monitored in order to satisfy with the food safety regulations [92, 93]. Nevertheless, Pan et al. [91] reported the presence of several organophosphorus pesticides (OPs), such as chlorpyrifos, diazinon, isofenphos-methyl, phorate, and profenofos that would have not been registered for use in L. barbarum berries in China, thus questioning the intended use of these pesticides in such fruits and their associated risks for human health. The levels of pesticides (difenoconazole, fluxapyroxad, fluopyram, and cyantraniliprole) were assessed through an acute and chronic risk assessment conducted for measuring the dietary pesticide residue exposure, which showed that they are directly influenced by the processing technique (such as sun or oven drying, decoction, brewing) used [94].

Apart from tropane alkaloids and chemical contaminants such as pesticides and heavy metals, allergic and anaphylactic reactions, although rare, occurred after ingestion of L. barbarum fruits. Interestingly, individuals with food allergies, especially those allergic to lipid transfer proteins would likely be at risk of developing an allergic reaction from the consumption of L. barbarum berries [95, 96]. Cross-reactivity of L. barbarum berries in conjunction with peach, tomato, nuts, and Artemisia sp. pollen was shown to occur in individuals due to the involvement of these allergic proteins [24]. Anaphylactic reactions associated with the ingestion of L. barbarum fruits are also mentioned [97].

Interactions between L. barbarum and medication are relatively unknown, in which individuals taken prescription medicine in conjunction with goji berries could be predisposed to potential health associated risks. The development of flecainide toxicity in an old woman patient was previously linked with the consumption of L. barbarum tea, taken as a preventative measure against Covid-19, thus increasing awareness among clinicians on the possible drug-herb interactions [98]. Other drug-herb interactions showed the possible effects of oral anticoagulants, such as warfarin, leading to an increased risk of bleeding when used concomitantly with L. barbarum fruits such as tea, juice, or wine [99].

Despite several side effects L. barbarum may have on human health, possibly linked to overconsumption or in conjunction with specific medication, their richness in valuable bioactive compounds can positively impact human health. Besides, pesticides, tropane alkaloids, and metals concentrations in L. barbarum berries investigated by several authors showed adherence within the maximum residue levels, in agreement with safety concerns [84, 90, 91]. However, there is a lack of toxicological data and an absence of studies in animals and humans regarding the intake of L. barbarum berries in larger quantities over a prolonged period of time [100]. Despite their increased consumption in European countries, there is no specific regulation on the intended use of L. barbarum berries. Although its health-related benefits and different applications of L. barbarum (Figure 2) as tea, production of beverages, functional ingredients in confectionary and baked goods, and milk or meat-related products, L. barbarum berries are not regulated under the EU novel food legislation [24, 101]. Moreover, caution should be taken when consumed as several studies suggested that may trigger allergic reactions, especially in chronic individuals [96].

Conclusion

This comprehensive review has elucidated the multifaceted health benefits of L. barbarum, a botanical known for its diverse pharmacological properties and traditional uses. L. barbarum demonstrates significant therapeutic potential across a wide range of health conditions due to their diverse biological activities. The pharmacokinetics of L. barbarum supports its efficacy in promoting antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory activities. Human studies further substantiate L. barbarum’s role in improving metabolic health, cardiovascular function, glycaemic control, and mitigating conditions such as NAFLD and cancer. In addition to its therapeutic benefits, L. barbarum’s neuroprotective, hepatoprotective, and prebiotic activities, as well as its anti-aging and ocular health effects, highlight its broad applicability in addressing chronic diseases and enhancing overall health. However, while promising, these findings also underscore the need for further clinical research, particularly large-scale, controlled studies, to better understand its mechanisms of action, optimal dosing, and long-term safety. Overall, L. barbarum offers an exciting natural intervention with considerable potential for future therapeutic applications, although more rigorous investigation is necessary to fully integrate it into modern clinical practice.

Abbreviations

| AMD: | age-related macular degeneration |

| BOEC: | blood outgrowth endothelial cell |

| CVD: | cardiovascular disease |

| HDL: | high-density lipoprotein |

| HDP: | healthy dietary pattern |

| IgG: | immunoglobulin G |

| IL: | interleukin |

| L. barbarum: | Lycium barbarum |

| L. chinense: | Lycium chinense |

| LAK: | lymphokine-activated killer |

| LBPs: | Lycium barbarum polysaccharides |

| LWB: | Lacto-Wolfberry |

| MDD: | major depressive disorder |

| MPOD: | macular pigment optical density |

| MS: | metabolic syndrome |

| NAFLD: | non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| PPEE: | postprandial energy expenditure |

| RP: | retinitis pigmentosa |

| StD: | subthreshold depression |

Declarations

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the School of Food Science and Environmental Health at Technological University Dublin, Grangegorman, for providing the resources and support necessary to undertake this final-year research project as part of the BSc (Hons) Pharmaceutical Healthcare programme. The authors also extend their appreciation to Mr. Rhys Walsh for his collaborative efforts and contributions to the overall project.

Author contributions

TZ: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Supervision. EAA: Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Supervision. AB and RK: Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

Publisher’s note

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.