Affiliation:

College of Health Sciences, University of Memphis, Memphis, Tennessee, TN 38152, USA

ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1759-1778

Affiliation:

College of Health Sciences, University of Memphis, Memphis, Tennessee, TN 38152, USA

ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5823-2611

Affiliation:

College of Health Sciences, University of Memphis, Memphis, Tennessee, TN 38152, USA

ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7518-8066

Affiliation:

College of Health Sciences, University of Memphis, Memphis, Tennessee, TN 38152, USA

Email: bdpence@memphis.edu

ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4059-9092

Explor Immunol. 2023;3:442–452 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/ei.2023.00112

Received: July 06, 2023 Accepted: August 18, 2023 Published: October 11, 2023

Academic Editor: Roberto Paganelli, G. d’Annunzio University, Italy

The article belongs to the special issue Immunosenescence: Mechanisms and Its Impact

Immunosenescence encompasses multiple age-related adaptations that result in increased susceptibility to infections, chronic inflammatory disorders, and higher mortality risk. Macrophages are key innate cells implicated in inflammatory responses and tissue homeostasis, functions progressively compromised by aging. This process coincides with declining mitochondrial physiology, whose integrity is required to sustain and orchestrate immune responses. Indeed, multiple insults observed in aged macrophages have been implied as drivers of mitochondrial dysfunction, but how this translates into impaired immune function remains sparsely explored. This review provides a perspective on recent studies elucidating the underlying mechanisms linking dysregulated mitochondria homeostasis to immune function in aged macrophages. Genomic stress alongside defective mitochondrial turnover accounted for the progressive accumulation of damaged mitochondria in aged macrophages, thus resulting in a higher susceptibility to excessive mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) leakage and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. Increased levels of these mitochondrial products following infection were demonstrated to contribute to exacerbated inflammatory responses mediated by overstimulation of NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome and cyclic GMP-ATP synthase (cGAS)-stimulator of interferon genes (STING) pathways. While these mechanisms are not fully elucidated, the present evidence provides a promising area to be explored and a renewed perspective of potential therapeutic targets for immunological dysfunction.

Immunosenescence refers to the age-related physiological dysregulation of immune responses, which accounts for the increased susceptibility to infections, autoimmune diseases, and cancer in the elderly [1, 2]. The homeostatic imbalance of the immune system is reflected in an impaired adaptative immune response accompanied by a compensatory exacerbation of innate immune activation [3]. This imbalance underpins the low-grade chronic inflammatory state observed in older adults, i.e., inflammaging, pointed out as an underlying cause of age-related diseases [2, 3]. In addition, this phenotype correlates with a higher risk of severe outcomes during acute infections, as exemplified by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) [4], influenza [5], and respiratory syncytial infections [6]. In this regard, elucidation of the mechanisms behind the age-related adaptations of the immune system is of major interest to the field of geroscience.

Macrophages are key tissue sentinel cells implicated in host defense and tissue homeostasis [7]. These innate cells contribute to the production of inflammatory mediators in sterile and infectious contexts [7, 8], a function that is dysregulated in aging. Aged macrophages are hyperresponsive to inflammatory stimuli and display a limited resolution potential, thus favoring the exacerbation of inflammation and local damage [9, 10]. In parallel, a decline in specific functions is also observed [11], such as phagocytosis, antigen presentation, and oxidative burst, thus further contributing to impaired resolution and defective activation of adaptative immunity [12]. Although multiple age-related adaptations have been linked to this phenotype, such as genomic stress [13], overstimulation by inflammatory ligands, and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress [14], the underlying mechanisms remain obscure.

In recent years, a new perspective has emerged with the advance of the immunometabolism field, focused on the crosstalk between metabolic adaptations and immunity. It has become clear that metabolic rewiring is a critical aspect of immune activation required to sustain functionality, and modulating it directly impacts immunity [15]. In this regard, mitochondria have gained a renewed interest in regulating immune responses due to their key role in metabolic adaptations [16]. Besides, mitochondria have been directly implicated in coordinating multiple innate immune pathways by acting as a signaling center [17]. These findings are of particular interest to immunosenescence given that mitochondrial function declines during biological aging [18], and a correlation with impaired immune response has been observed in different cell types [19–21]. As such, elucidation of the mechanisms connecting both phenotypes may provide new insight for therapeutic approaches.

Despite recent evidence on the topic, the underlying mechanisms linking mitochondrial and immune age-related phenotypes remain largely unexplored. This review aims to provide a perspective on the recent advancements in the field by compiling key publications from the past several years focused on macrophages. The presence of insults in aged macrophages that drive mitochondrial dysfunction and how it translates into a dysregulated inflammatory phenotype will be briefly discussed. The goal of this review is to give a state-of-the-art view of current knowledge and potential gaps to be addressed by future research.

Immune response is interconnected to mitochondrial metabolic and physiological adaptations, which are required to sustain energetic and biosynthetic demands as well as to coordinate inflammatory pathways [22, 23]. For instance, distinct macrophage activation states rely on specific mitochondrial metabolic shifts [23]. Simplistically, inflammatory signals drive rewiring of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle concomitant to disruption of the electron transport chain (ETC), while anti-inflammatory signals promote reinforcement of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and reliance on fatty acid oxidation. Defects in these metabolic shifts impact proper immune activation and function [24]. In addition, mitochondria act as a platform for multiple innate immune signaling pathways mediated by mitochondrial outer membrane proteins [e.g., mitochondrial antiviral signaling (MAVS) protein] [17] and calcium (Ca2+) flux [25]. Finally, mitochondria govern a delicate balance of cell life and death through mechanisms such as apoptosis and autophagy, which are essential for maintaining immune homeostasis and controlling inflammation [26].

Aging is accompanied by a progressive decline in mitochondrial function and fitness, a phenomenon crucially implicated in the development of age-related diseases [18] and linked to the dysregulated immune response found in aged individuals [20]. Mitochondrial dysfunction is characterized by increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and accumulation of oxidative damage and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutation, thus coupled to reduced energy efficiency and membrane potential [27]. While altered mitochondrial dynamics, mitophagy, and biogenesis usually account for the accumulation and propagation of damage in the mitochondrial network [27], distinct drivers observed in aged cells such as genomic stress [28], ER stress [29], and dysfunctional nutrient sensing pathways [30] have also been implicated. Not surprisingly, those drivers have also been observed in senescent immune cells [14, 31], but how they modulate mitochondrial function in these cells and how it correlates to immune response is not fully elucidated.

Aged macrophages share multiple similarities with senescent cells including adaptations with a direct impact on mitochondrial function [14, 31]. For instance, excessive ROS production is classically observed in both conditions, which is mostly attributed to defects in mitochondrial integrity and antioxidant defenses [32, 33]. In addition, chronic inflammatory activation has been shown to contribute to exacerbated ROS production through inflammasome stimulation in alveolar macrophages [34]. Furthermore, genomic stress has also been linked to increased susceptibility to oxidants and ROS accumulation under basal conditions and upon stimulation [32, 35]. While the cited conditions contribute to ROS production thus favoring mitochondrial damage and dysfunction, they also create an amplification loop given that ROS per se modulates inflammatory response as well as genomic stress [36, 37].

The second shared aspect is the decline of intracellular nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) availability [9], a central regulator of cellular metabolism and immune function [38]. Aging is associated with decreased NAD+ synthesis and recycling in macrophages, which relates to an inflammatory shift and impaired oxidative metabolism [9]. Besides, NAD+ decline is further aggravated by enhanced expression and activation of CD38 in aged macrophages [39], thus negatively impacting mitochondrial function and homeostasis [30]. This detrimental effect may be partially mediated by impaired transcriptional activity of sirtuins, NAD-dependent enzymes involved in orchestrating metabolic and immune functions [40, 41]. Of note, sirtuin 1 and sirtuin 3 are associated with the regulation of mitochondrial oxidative metabolism as well as oxidative stress response, both impaired in aging [41–43]. Dysregulated NAD+ metabolism has also been associated with alterations in distinct inflammatory pathways in aging and represents a growing area of interest, as reviewed elsewhere [44, 45].

Sustained ER stress has been recently addressed as another key player in macrophage age-related metabolic alterations [14], which has also been coupled with mitochondrial dysfunction [29, 46]. ER stress can be induced by distinct conditions commonly observed in age-related chronic disorders, such as nutrient excess, inflammation, and hypoxia, thus leading to activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR) [47]. Additionally, aging is associated with reduced UPR and limited capacity to resolve ER stress [48], further contributing to establishing a persistent phenotype. ER stress-mitochondria crosstalk has been shown to be mediated by inositol-requiring enzyme 1 α (IRE1α) activation, which promotes mitochondrial ROS (mtROS) production and NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3)-caspase 2 activation, thus leading to mitochondrial damage and extravasation of mitochondrial contents [46]. Furthermore, ER and mitochondria cooperate to regulate Ca2+ homeostasis, and perturbations in this balance can contribute to dysregulated Ca2+ signaling and mitochondrial membrane potential impairment [14, 25].

Finally, telomeric attrition has been highlighted as a negative modulator of immune function. Bone marrow-derived macrophages originated from mice with telomere dysfunction have been shown to display exaggerated inflammatory responses to infection associated with mitochondrial stress and oxidative stress [35, 49]. Besides, impaired antioxidant response and enhanced production of mtROS are also observed [32]. While distinct mechanisms have been proposed to connect both phenotypes, this connection remains sparsely explored and has been only recently addressed.

As discussed above, altered mitochondrial metabolism, dynamics, and function are intrinsic features of aged macrophages. While the emergence of those features is not an isolated aspect of senescence [31], recent studies have pointed out mitochondrial dysfunction as a central node in immune dysregulation [35, 49–51]. In particular, mtDNA has gained great attention as a link between those two phenotypes [52]. mtDNA is released into the cytosol by injured mitochondria thus acting as a potent stimulator of intracellular DNA-sensing antiviral mechanisms which culminate in the expression of pro-inflammatory and interferon genes [53, 54]. Considering that aged macrophages accumulate defective mitochondria and are more susceptible to mtDNA cytosolic leakage [35, 49, 51], a causal connection could be drawn between enhanced basal inflammation observed in these cells and mitochondrial dysfunction.

Recently, the cyclic GMP-ATP synthase (cGAS)-stimulator of interferon genes (STING) pathway has been implied as a main pathway to mtDNA inflammatory stimulation [52, 54]. Enhanced cGAS-STING activation is observed in multiple chronic inflammatory disorders and infections commonly associated with aging and has been described as a key player in immunosenescence and inflammaging [55, 56]. For instance, Zhong et al. [51] have demonstrated STING activation in macrophages is exacerbated in ischemia and reperfusion injury in aged livers, which thus correlates to increased cytosolic leakage of mtDNA. When comparing young and aged macrophages, they observed impaired mitophagy in aged cells as a leading cause of accumulation of injured mitochondria and mtDNA release.

Increased susceptibility to damage is also noted in infectious contexts, resulting in an exaggerated inflammatory response. Using a mice model of premature aging with dysfunctional telomeres, Lv et al. [35] demonstrated a higher vulnerability to influenza A virus infection associated with exacerbated cGAS-STING and NLRP3 activation. This phenotype was attributed to aggravated mitochondrial distress in senescent macrophages following infection and consequent mtDNA release. In accordance, Plataki et al. [50] also observed aged lung macrophages to be more susceptible to disruption of mitochondrial membrane potential and ATP production following Streptococcus pneumoniae infection, which culminated in augmented mtDNA leakage and oxidative stress. Considering that macrophages are implied as a cornerstone of inflammatory hyperactivation in respiratory infections, such as SARS-CoV-2, in the elderly [4, 57], these data provide a great insight into new mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets to be explored.

As previously debated, enhanced ROS production and oxidative stress are intrinsic to mitochondrial dysfunction [27] and have also been proven to drive inflammation per se. In particular, these stressors directly modulate NLRP3 inflammasome activation [58], which is implicated in aging and aging-associated diseases [59, 60]. In another study using a similar mice model with dysfunctional telomeres, Kang et al. [49] demonstrated an increased burden of mitochondrial morphological and functional abnormalities in senescent macrophages following Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) infection. Inhibition of mtROS production and signaling largely abrogated hyperactivation of NLRP3 inflammasome, implicated as a central node in the exacerbated inflammatory response to S. aureus infection. It is interesting to note that Lv et al. [35] have also observed enhanced mtROS production and NLRP3 activation in senescent macrophages, which may corroborate Kang et al. [49], although this relationship was not addressed. Furthermore, oxidized mtDNA has also been shown to fuel NLRP3 activation [61], and enhanced levels of these molecules are observed upon mitochondrial damage in macrophages.

Despite some evidence having also been provided on other potential mechanisms linking mitochondrial phenotype and immune function in aged macrophages, their connection remains sparsely explored. For instance, defects in NAD metabolism were shown to promote a rearrangement of the mitochondrial network around the nucleus coupled with an enhanced stimulation of NLRP3 inflammasome [62]. Besides, disturbed mitochondrial Ca2+ regulation due to decreased membrane potential correlates with increased Ca2+ cytosolic levels and activation of several inflammatory pathways [63]. Finally, it was recently demonstrated that compromised OXPHOS following M1-like macrophage activation undermines M2-like repolarization upon interleukin 4 (IL-4) stimulation [64]. This finding further corroborates the observation that aged macrophages are more prone to an inflammatory profile [10], pointing out impaired mitochondrial metabolism as a leading cause.

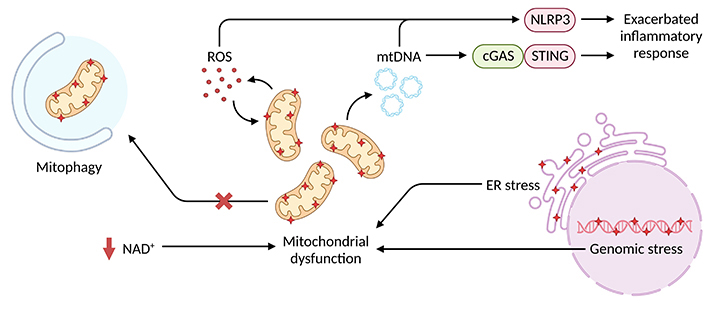

In summary, the key studies highlighted above [35, 49–51, 62] reinforce the crucial role of mitochondrial fitness in modulating inflammatory response intensity in aged macrophages (Figure 1). Curiously, however, basal inflammatory levels were only slightly elevated in comparison to young macrophages [35, 49, 51], which suggests mitochondrial insults alone may not evoke inflammation per se but prime exacerbated response upon injury or infection. Either way, therapeutic approaches focusing on mitochondrial dysfunction may provide an effective treatment for age-related inflammatory diseases.

Intracellular stressors associated with mitochondrial dysfunction and inflammatory exacerbation in aged macrophages. Genomic and ER stress alongside defective NAD+ metabolism and autophagy favor the disruption of mitochondrial homeostasis and accumulation of damaged mitochondria, which are more susceptible to mtDNA and mtROS leakage. Increased cytosolic levels of these mitochondrial products overstimulate NLRP3 inflammasome and cGAS-STING pathways thus promoting an exacerbated inflammatory response

Present evidence provides a promising perspective on elucidating mitochondrial dysfunction crosstalk with a dysregulated inflammatory response in aged macrophages. However, several avenues remain to be explored and the provided studies underscore the crucial need for a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms to prevent and control deleterious effects of dysfunctional immune activation. While recent papers reinforce the key role of cGAS-STING and inflammasome activation mediated by enhanced mtDNA and mtROS leakage [35, 49–51, 62], several other potential mechanisms linking mitochondrial fitness and immune response lack exploration. For instance, MAVS coordinates intracellular antiviral response [17], and its activity is dependent on intact mitochondrial membrane potential and OXPHOS [65], both compromised in senescent cells [27]. In accordance, aged monocytes present impaired mitochondrial respiratory capacity [66] and reduced interferon regulatory factor (IRF) 3 and 7 activation [67], downstream to MAVS signaling [68], thus suggesting a plausible involvement of this pathway in deficient antiviral response, although no direct evidence has been presented. Besides that, Ca2+ signaling has been implicated in STING modulation, raising the question of whether dysregulated mitochondrial Ca2+ flux control may also be involved in exacerbated STING response [25, 63].

As pointed out before, macrophage inflammatory response upon damage or infection stimulation, but not at basal state, was exacerbated due to higher mtDNA cytosolic leakage [35, 49, 51]. Despite not adding to increased basal inflammation, sustained higher levels of mitochondrial-derived products may correlate with distinct adaptations in aged macrophages that culminate in impaired function. Of note, decreased responsiveness is observed following higher doses of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) due to receptor desensitization, a phenomenon known as immune tolerance [69]. Indeed, aged macrophages present diminished responsiveness to stimuli as well as reduced expression of receptors [e.g., Toll-like receptors (TLRs)] [24, 70, 71], thus suggesting epigenetic alterations also play a critical role. Whether higher mtDNA content per se may engage these adaptations remains to be elucidated, and evaluation of the epigenetic landscape can be a potential tool to explore this connection.

Mitochondrial dysfunction is rather an integrated feature of senescence than an isolated phenomenon [31], making it difficult to define its intrinsic contribution. In this sense, recent studies exploring mitochondrial transplantation techniques on the whole body or isolated cells pave a great avenue to address a more individualized role of mitochondria in aged immune cells [72]. Transferring mitochondria from young to aged macrophages, and vice versa, may provide a better clue as to whether renewing the mitochondrial network can restore dysregulated immune response or if the instituted senescence-related insults would sink mitochondrial function. Besides, these results can provide promising therapeutic opportunities.

Finally, some of the presented studies have demonstrated that directly targeting mtROS production largely ablates exacerbated inflammatory response [35, 49, 50]. These results not only reinforce the central role of dysregulated ROS signaling as a leading cause of cellular dysregulation [36] but also highlight the use of antioxidants for attenuating inflammatory disorders in age-related conditions. In addition, senomorphics have also been postulated as promising therapeutic approaches for immune dysfunction and further corroborated the key role of mitochondria in immunity given their major effect on mitochondrial dynamics [73].

Loss of mitochondrial homeostasis and integrity lay at the basis of multiple age-related disorders [18]. Recent data explored in this review provide a complementary perspective on how the decline in the mitochondrial function in the immune system may further contribute to these disorders. Adding this extra layer of complexity not only paves the way for exploring new therapeutic approaches but also reinforces mitochondria as a promising target implicated on multiple levels. A potential application example of this perspective is chronic respiratory diseases commonly associated with aging, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD) and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) [74].

COPD and IPF have been shown to present a strong association between mitochondrial dysfunction and disease progression. Excessive mtROS production due to compromised mitochondrial membrane potential and cumulative mitochondrial damage have accounted for the propagation of epithelial barrier injury in both disorders, thus contributing to tissue remodeling and inflammatory activation [74, 75]. Additionally, enhanced mtROS production in IPF has been associated with prolonged DNA damage and induction of senescence in fibroblasts, an aggravating condition [76]. While those evidence refers mostly to non-immune cells, markers of mitochondrial dysfunction are also observed in alveolar macrophages which further contribute to tissue oxidative stress and fibrosis [77]. Furthermore, increased levels of mtDNA are detected in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and plasma of IPF subjects [78], which provides another potential connection between tissue mitochondrial dysfunction and inflammatory exacerbation.

Despite the observation of disturbed mitochondrial physiology in distinct cell populations, elucidating how they correlate to each other or whether they have similar origins remains to be explored. Besides, a great focus has been given to the effectiveness of antioxidants in non-immune cells [79, 80], lacking an integrative assessment. Nevertheless, targeting mitochondrial dysfunction in a broad spectrum can prove to be a robust approach to treating these conditions. In addition to the respiratory diseases used as an example here, mitochondrial dysfunction has links to myriad age-related diseases including neurodegenerative disease [81], atherosclerosis and other heart diseases [82], and cancer [83] among many others. As such, therapies in this area are likely to have broad implications for disease treatment.

Exploring the underlying mechanisms driving immunological dysregulation in aging remains a central topic of interest for geroscience when elucidating age-related inflammatory diseases and addressing new therapeutic approaches. Recent studies connecting immunity to cellular metabolic adaptations have paved the way for new perspectives in the field and a renewed interest in mitochondrial dynamics and fitness. Loss of mitochondrial homeostasis in aged macrophages has been demonstrated to contribute to exacerbated inflammatory responses mediated by overstimulation of NLRP3 inflammasome and cGAS-STING pathways. While mitochondrial-derived products (e.g., mtDNA and mtROS) have been pointed out as major connectors between mitochondria and inflammatory phenotypes, several other mechanisms remain to be explored. Nevertheless, the presented evidence provides a promising area to be addressed and a renewed perspective on therapeutic targets for immunological dysfunction.

Ca2+: calcium

cGAS: cyclic GMP-ATP synthase

ER: endoplasmic reticulum

IPF: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

MAVS: mitochondrial antiviral signaling

mtDNA: mitochondrial DNA

mtROS: mitochondrial reactive oxygen species

NAD: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

NLRP3: NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3

OXPHOS: oxidative phosphorylation

ROS: reactive oxygen species

STING: stimulator of interferon genes

RMM: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. BLS and NM: Writing—original draft. BDP: Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing, Supervision. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The study was supported by National Institute on Aging [R15AG078906] and American Heart Association [19TPA34910232] to BDP. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

© The Author(s) 2023.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2023. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Fidaa Bouezzedine ... Georges Herbein

Pitu Wulandari

Valquiria Bueno

Roberto Paganelli, Angelo Di Iorio

Natasa Strbo ... Alessia Paganelli