Abstract

In recent years, immunologists have been working to utilize the functional mechanism of the immune system to research new tumor treatment methods and achieved a major breakthrough in 2013, which was listed as one of the top 10 scientific breakthroughs of 2013 by Science magazine (see “Cancer immunotherapy”. Science. 2013;342:1417. doi: 10.1126/science.1249481). Currently, two main methods are used in clinical tumor immunotherapy: immune checkpoint inhibitors and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells. Clinical responses to checkpoint inhibitors rely on blockade of the target neoantigens expressed on the surfaces of tumor cells, which can inhibit T cell activity and prevent the T cell immune response; therefore, the therapeutic effect is limited by the tumor antigen expression level. While CAR-T cell therapy can partly enhance neoantigen recognition of T cells, problems remain in the current treatment for solid tumors, such as restricted transport of adoptively transferred cells to the tumor site and off-targets. Immunologists have therefore turned their attention to γδ T cells, which are not restricted by the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) for neoantigen recognition and are able to initiate a rapid immune response at an early stage. However, due to the lack of an understanding of the antigens that γδ T cells recognize, the role of γδ T cells in tumorigenesis and tumor development is not clearly understood. In the past few years, extensive data identifying antigen ligands recognized by γδ T cells have been obtained, mainly focusing on bisphosphonates and small-molecule polypeptides, but few studies have focused on protein ligands recognized by γδ T cells. In this paper, we reviewed and analyzed the tumor-associated protein ligands of γδ T cells that have been discovered thus far, hoping to provide new ideas for the comprehensive application of γδ T cells in tumor immunotherapy.

Keywords

γδ T cells, tumor-associated protein ligands, immunotherapyIntroduction

T cells in humans can be divided into αβ T and γδ T cells according to different T cell receptors (TCRs), which are both derived from a thymus precursor but have different roles and functions in the immune system [1]. In the past few decades, considerable progress has been achieved in the process of αβ T cell-specific recognition and presentation of tumor antigens and cytotoxicity, which has been applied in tumor immunotherapy. However, when αβ T cells recognize major changes in cell surface antigens in the development of tumors, major histocompatibility complex (MHC) restriction requires tumor antigens to be presented with a self-MHC molecule, which complicates αβ T cell immune system transfer between different individuals [2]. Unlike αβ T cells, γδ T cell antigen recognition requires no MHC restriction, and many kinds of antigens can be recognized, such as small phosphate molecules, phospholipids, sulfides, soluble proteins, and small-molecule polypeptides. Because of this characteristic, tumor antigen ligands recognized by γδ T cells and their application in immunotherapy have become a new trend [3, 4]. Meanwhile, γδ T cells are able to respond rapidly to transforming and pathogenic stresses in malignant tumors [5], for example, γδ T cells are the earliest producers of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) in the tumor microenvironment [6]. γδ T cells utilize various surface receptors natural killer group 2 member D (NKG2D), tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL), Fas ligand (FasL) and their own production, the dual role of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), IFN-γ, granzyme B and perforin, to produce cytotoxic effects on tumor cells [7, 8].

Different subtypes of γδ T cells have different functions, and the results of research on total γδ T cells in the context of the tumor microenvironment or tumor immunotherapy are not always consistent. In our study, recombinant MHC class I chain-related A (MICA) effectively amplified δ-chain variable region 1 (Vδ1)+ T cells in human ovarian epithelial carcinoma and colon epithelial carcinoma tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in vitro, and these cells had strong cytotoxicity to tumor cells expressing MICA [9]. A study developed a method that allows large-scale expansion and differentiation of cytotoxic Vδ1+ T cells by resuspending sorted γδ T cells in serum-free cultures (Op Tmizer-CTS) containing human cytokines interleukin-4 (IL-4), IFN-γ, IL-21, IL-1β, and soluble CD3 multiple antibodies, and in a preclinical chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) model to test its therapeutic potential. They inoculated NSG mice with MCE-1 cells and de-treated them with amplified Vδ1 T cells and showed that the survival time of the cell-treated animals was significantly longer, including one case of tumor regression, and the overall survival data demonstrated the effectiveness of the treatment [10]. Ten patients with recurrent nonsmall cell lung cancer received γδ T cell immunotherapy. They received autologous γδ T cell reinfusion 3–12 times (mean = 6) every 2 weeks. According to the evaluation criteria for the efficacy of solid tumors, none of the patients achieved complete or partial symptom relief, but no serious adverse reactions occurred [11].

Vγ9Vδ2 T cells are the most abundant subpopulation of γδ T cells in the blood. Vγ9Vδ2 T cells are widely believed to be able to attenuate tumor progression in a variety of in vitro and in vivo tumor models and have advantages in tumor immunotherapy. Professor Yin Zhinan’s team carried out a phase I clinical trial of allogeneic Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. Among 132 late-stage cancer patients, 8 liver cancer patients and 10 lung cancer patients who received ≥ 5 cell infusions survived more than 10 months, which certified the safety and effectiveness of allogeneic Vγ9Vδ2 T cell immunotherapy [12]. At the same time, a study has shown that using a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) targeting GD2 as a model system, the amplified CAR-transduced Vδ2 cells retain the ability to recognize tumor antigens and cross-present processed peptides to responder αβT lymphocytes, and the modified Vδ2 cells also possess a toxic effect on antigen-specific cells [13]. Some studies suggest that IL-17 γδ T cells play a role in promoting the process of tumor development in the immune microenvironment, but Vδ1 and Vδ2 γδ T cells are strong candidates for cancer cell therapy.

Current research has clarified that CD4+ and CD8+ αβ T cells can recognize presented polypeptide antigens via MHC class II and class I molecules [14, 15]. However, no clear mechanism has been identified for specific antigen recognition by γδ T cells and how such antigens are presented. Identifying more ligands recognized by γδ T cells and clarifying the mechanism of γδ T antigen recognition will facilitate the pursuit of further functional clinical applications.

γδ T cell subsets

We can divide γδ T cells into three main subgroups of Vδ1, Vδ2, and Vδ3 according to the different patterns of Vδ gene expression [16]. Vδ1 γδ T cells are mainly distributed in the thymus and mucosal epithelial tissues, with only a few in peripheral blood [17]. Human Vδ2 chains almost only pair with Vγ9 chains and are also called Vγ9δ2γδ T cells. Vγ9δ2γδ T cells are mainly distributed in peripheral blood, accounting for up to 50–90% of total γδ T cells, and are the main circulating γδ T lymphocytes in healthy adults [18]. Vδ3γδ T cells mainly exist in the liver, and very few Vδ3γδ T cells are present in the blood. Vδ3γδ T cells are the least abundant γδ T cells in the body, accounting for only 0.2% of circulating γδ T cells [19]. In contrast to the adaptive biology of some Vδ1+ subpopulations, Vδ2+ T cells appear to be better suited than Vδ1+ subpopulations to play the role of innate T cells using a semi-mutant TCR. However, this distinction between innate Vδ2+ and adaptive Vδ1+ T cells does not fully cover the full diversity of γδ T cell subpopulations, ligands and interaction patterns [20].

Vδ1 γδ T cells express natural killer (NK) cell receptors, Toll-like receptors (TLRs), and CD8 on the surface, and CD8+ Vδ1γδT cells mainly exist in interepithelial lymphocytes. The surface of Vδ2 γδ T cells expresses NKG2D, TLRs, and CD45 [16]. Vδ3γδ T cells express CD56, CD161, human leukocyte DR isotype antigen and NKG2D [21]. NKG2D is a receptor expressed on cytotoxic cells, including γδ T lymphocytes. Binding of the proteins binding to cytomegalovirus glycoprotein UL16-binding protein (ULBP) ligand to NKG2D activates cytotoxic effector T lymphocytes and enhances the effector function mediated by the T cell receptor [22]. ULBP1-4 can be constitutively expressed on the cell surface under the stress of the tumor microenvironment and then recognized by Vδ1 T cells [23]. MHC class I-related molecules (MR1) are expressed primarily in human small intestinal epithelial tissues and can be recognized by Vδ1 T cells in human small intestinal epithelial cells together with their closely related MICB [24]. Vδ1 T cells interact with the α1 and α2 domains of MICA/B through NKG2D and can act as immunotest detectors to detect damaged intestinal epithelial tissues, while MICA/B can stimulate T cells to secrete growth factors to maintain the homeostasis of epithelial cells [25]. Vδ2 γδ T cells can also recognize and bind MICA/B and ULBPs through NKG2D, and the signal is later transmitted to tyrosine kinase. Upon interaction between NKG2D and its ligands, MICA and ULBP, the tyrosine kinase becomes activated to catalyze the activation and proliferation of immune cells to enhance the body’s antitumor immunity [26, 27]. Culture of peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) with either the solid-phase chemotactic NKG2D-specific mAb or MICA, a ligand for NKG2D, revealed that MICA induced upregulation of CD69 and CD25 in NK and Vγ9δ2 T, but not in CD8 T cells [28]. Expression of ULBP molecules was found in several types of cancer (leukemia, lymphoma, ovarian, colon and hematological malignancies), suggesting that Vγ9Vδ2 T cell-mediated cytolysis is susceptible to a wide range of tumor cells [29, 30].

Besides, γδ T cells recognize and trigger antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) via CD16 binding to the Fc fragment of immunoglobulin G (IgG) to kill tumor cells [31]. CD16+ Vδ2 T cells have more cytolytic potential than CD16− T cells and share many characteristics of mature NK cells, including killer cell immunoglobulin like receptors (KIR) expression [32]. An article showed that CD16 (FcRIIIA) is specifically expressed by most human cytomegalovirus (HCMV)-induced T cells and further investigated their cooperation with anti-HCMV IgG. They found that CD16 could stimulate T cells independently of TCR engagement and provide an intrinsic potential for ADCC for their stimulation of T cells [33]. In one report, a specific redirected lysis model using the mouse FcγR+ cell line P815 was used to clearly demonstrate that the γδ T cell receptors TCR Vγ9Vδ2, NKG2D and CD16 are all inhibited by prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). They first co-cultured γδ T cells with anti-TCR Vδ2 mAbs of FcγR+ mouse mast cell line P815, stimulated Vγ9Vδ2 T cells with synthetic phosphoantigen bromohydrin pyrophosphate (pAg-BrHPP), analyzed their intracellular production of IFN-γ and TNF-α, and found that PGE2 at 1 μg/mL inhibited the production of these cytokines [34].

γδ TCR ligands

Non-Vγ9δ2 T cells recognize antigen proteins on the surfaces of tumor cells

In addition, Vδ1 T cells can be activated by the superantigen staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB), which can promote the proliferation of γδ T cells and the secretion of IFN-γ [35]. The CD1 family consists of MHC-like antigen-presenting molecules, and CD1c is usually expressed in antigen-presenting cells (APCs). Studies have shown that Vδ1 T cells specifically recognize CD1c molecules of the nonpolymorphic CD1 family that are expressed only in APCs when they present lipid and glycolipid foreign antigens to T cells [36]. CD1c-specific Vδ1 T cells are cytotoxic and can lyse infected dendritic cells via the perforin pathway and kill intracellular bacteria by secreting granulysin B [37]. Recombinant Vδ1 TCRs from different individuals can bind to the recombinant CD1d-sulfide complex, which directly demonstrated for the first time that γδ TCRs could specifically recognize MHC-like restricted antigens. Although Vδ1 T cells can recognize CD1d, the origin and function of Vδ1+CD1d sulfatide-responsive T cells remain to be explored [38]. Julie Mechane-Merville demonstrated HCMV-specific expression of the Vγ9/Vδ1 TCR and specific identification of an adrenergic receptor A2 [ephrin type-A receptor 2 (EphA2)] clone [39].

Vδ1 and Vδ2 γδ T cells have been studied extensively, but few studies have examined Vδ3 γδ T cells. Vδ3T cells amplified with IL-2 have been reported to recognize CD1d-presenting antigens. Mangan et al. [21] reported that CD1d-expressing HeLa cells can proliferate among Vδ3 T cells, while expanded Vδ3T cells can recognize CD1d but not CD1a, CD1b or CD1c. When activated, they kill CD1d+ target cells, release T helper 1 (Th1), Th2, and Th17 cytokines, and trigger the maturation of dendritic cells [21]. Annexin A2 (ANXA2) expressed by tumor cells in response to reactive oxygen species (ROS)-dependent stress can be directly recognized by the Vγ8Vδ3 TCR. ANXA2-specific γδ T cells may be amplified under stress conditions to initiate an immune response faster than conventional αβ T cells [40]. Besides, Vδ3Vγ8 TCR clone can recognize antigen-presenting molecule monomorphic MR1. The determination of the structure of two Vδ3-Vγ8 TCR-MR1-antigen complexes revealed a recognition mechanism for the Vδ3 TCR chain, which mediates a specific contact with the MR1 antigen-binding groove side and represents a previously undescribed MR1 docking topology [41].

In addition to the three major subpopulations mentioned above, there exist other very small numbers of γδ T cells that are also capable of recognizing tumor-associated protein ligands. A human Vγ4Vδ5 clone binds directly to the endothelial protein C receptor (EPCR) in an antibody-like manner, enabling γδ T cells to recognize cytomegalovirus-targeted endothelial cells and epithelial tumors [42]. Besides, Vγ4 γδ T cells co-expressing Vδ1 or Vδ3 in the human intestine can recognize the butyryl proteins butyrophilin-like 3 (BTNL-3) and BTNL-8 in a TCR-dependent manner. Likewise, BTNL-1 and BTNL-6 are recognized by intestinal Vγ7+ cells through TCR-dependent responses [43].

Phosphonate antigen recognized by Vγ9δ2 T cells

At present, pAgs are acknowledged as tumor-associated antigens that can cause an immune response and γδ T cell expansion in human peripheral blood [44, 45]. Isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) is a representative endogenous pAgs and was the first explicitly reported tumor-associated ligand recognized by γδ T cells [46]. IPP is one of the intermediates of the mevalonate (MVA) metabolism pathway in vivo [47]. Normal levels of IPP do not induce the immune response of γδ T cells. However, in tumor cells, due to overactivation of the MVA pathway, high levels of IPP and other small pyrophosphate molecules accumulate, leading to γδ T cell activation [48], while zoledronic acid (ZOL) can inhibit the catabolism of IPP, therefore enhancing this process [49]. Recent clinical studies have shown that cancer patients treated with ZOL have an improved survival rate and increased γδ T cells [50, 51]. Meanwhile, (E)-4-hydroxy-3-methyl-but-2-ene pyrophosphate (HMBPP) produced by microorganisms from the nonmevalonate isoprenoid synthesis pathway can efficiently activate Vγ9Vδ2 T cells [52].

The recognition of pAgs by Vγ9Vδ2 requires cell-to-cell contact and depends on both Vγ and Vδ chains. Evidence has shown that this process involves the 3 different functional antigenic determinants complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) of γδ TCR, and the CDR3 region has a dominant role in antigen recognition. Early work by our laboratory verified that the primary structure of CDR3δ is the key to determining the specificity of antigen recognition by γδ TCRs [53]. The combination of pAgs and the intracellular domain B30.2 of type I transmembrane lactophilin butyrophilin 3A1 (BTN3A1) is currently believed to be able to activate γδ T cells. Mahboob Salim’s team used nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and X-ray crystallography to demonstrate that the negatively charged pAgs do not directly bind to the variable region of BTN3A1 but interact with the intracellular domain B30.2, which has a positively charged “pocket”, resulting in a conformational change at the distal end of the domain [54]. In addition, a similar mechanism for the recognition of HMBPP antigen by γδ T cells has been shown. The HMBPP 1-OH and the 351 histidines of B30.2 play an important role in the activation of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells [55]. At the same time, the synergistic action of BTN2A1 and BTN3A1 is required for antigen recognition and activation of γδ T cells. BTN2A1 can directly bind to the γδ T cell receptor through the Vγ9 coding region, and this interaction is different from the γδ TCR CDR3-dependent recognition of ligands. Although the BTN2A1-BTN3A1 complex was directly detected in the study, the possibility of parallel or sequential interactions between the Vγ9 TCR and BTN2A1 or BTN3A1 immunoglobulin V domains cannot be overlooked [56, 57]. The results from Jürgen Kuball’s group show that Vδ2T cells pass through a BTN-dependent tumor recognition process that begins with the binding of CDR2 and CDR3 of the TCR γ region to BTN2A1 [58]. The binding of CDR2 and CDR3 to BTN2A1 between CDR2 and CDR3, followed by the binding of TCR δ CDR3 to an as-yet-unrecognized ligand. This process is pAg-independent. Full activation of the γδ TCR requires pAg- and RhoB-dependent recruitment of BTN3A1 (together with BTN2A1) to the immune synapse [58]. BTN3A1 has been reported to activate αβ and γδ T cell antitumor responses [59]. The recognition of pAgs by γδ T allows it to rapidly initiate an immune response and act as a cytotoxic agent against tumor cells at an early stage of tumor development.

CD277/BTN3A plays a key role in pAg-induced activation of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, which can be counteracted by exposure of susceptible cells (tumor- and mycobacteria-infected cells, or aminodiphosphonate-treated cells with upregulated pAg levels) to antibody 103.2 against CD277. The activated Vγ9Vδ2 T cells can kill various hematologic and solid tumor cell lines [60]. A research has developed a humanized monoclonal antibody, ICT01, with subnanomolar affinity for the three isoforms of BTN3A, which can active Vγ9Vδ2 T cells effectively. The ICT01-activated V9V2 T cells can kill multiple tumor cell lines and primary tumor cells, but not normal healthy cells. A clinical trial of ICT01 monotherapy for advanced solid tumors or hematologic cancers was also designed in the paper. Six patients with solid tumors receiving ICT01 doses ranging from 20 to 700 grams. The investigators concluded that ICT01 was well tolerated, with no significant safety events or dose-limiting toxicities identified, and initially validated the safety of ICT01 treatment [61].

Clinically, pyrophosphate amine drugs such as ZOL are being used by numerous investigators to expand Vγ9Vδ2 T cells in vivo or in vitro combined with IL-2. In a phase I clinical trial, zoledronate, a Vγ9Vδ2 T cell agonist, and low-dose IL-2 were administered to 10 patients with terminally advanced metastatic breast cancer. A statistically significant correlation was found between the clinical outcomes and the number of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells in peripheral blood. Seven patients showed progressive clinical deterioration due to failure to maintain the peripheral blood Vγ9Vδ2 T cell population, while one of the three patients who maintained the peripheral Vγ9Vδ2 T cell population achieved partial remission, and the other two were stable [50]. In a phase I clinical trial of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC), 10 patients received autologous γδ T cell infusion. Reinfused γδ T cells were the patients’ own γδ T cells amplified with ZOL and IL-2 in vitro. Among these patients, tumor shrinkage was observed in 2 patients, and 6 patients were in stable condition [62]. Professor Yin Zhinan’s team used ZOL, IL-2, IL-15, and vitamin C to amplify γδ T cells derived from healthy people. 8 liver cancer and 10 lung cancer patients received more than 5 allogeneic γδ T cell infusions, and the survival times of 7 liver cancer patients and 9 lung cancer patients were significantly prolonged [12]. The above studies showed that although γδ T cell immunotherapy has a certain effect on tumors, complete remission of cancer may require combination therapy or personalized γδ T cell immunotherapy according to the specific conditions of the patient.

Identified tumor-associated protein ligands of Vγ9δ2 T cells

Except for bisphosphate antigens, mitochondrial F1-ATPase expressed on the surfaces of tumor cells can promote the recognition of tumors by Vγ9δ2 T cells. Purified F1-ATPase was demonstrated to selectively induce the activation of Vγ9δ2 T cells. Vγ9Vδ2 TCR and F1-ATPase binding to the defatted form of apolipoprotein A-I (Apo A-I) was demonstrated by surface plasmon resonance imaging, suggesting that tumor cells expressing F1-ATPase effectively activate Vγ9Vδ 2 T cells [63].

Our group successfully identified two self-proteins, heat shock protein 60 (HSP60) and human MutS homolog 2 (hMSH2), as ligands for Vδ2 T cells and performed affinity chromatography using synthetic CDR3 peptides as probes to confirm that they can be recognized by TCRδ2-expressing cells in peripheral blood [53]. As molecular chaperones, HSPs play a key role in protein folding [64]. At the same time, the expression of HSPs under stress was upregulated and involved in the immune response to various pathogens and tumors [65]. T cells of oral cancer patients can lyse allogeneic tumor cells by recognizing HSP60 on the surfaces of oral tumor cells [66]. hMSH2 is a highly conserved DNA key element mismatch repair protein usually located in the nucleus that forms the required dimer complexes with hMSH3 or hMSH6 to maintain genome integrity [67]. Recent findings indicate that hMSH2 plays an important role in DNA damage signal transduction and cell apoptosis [68]. Our team analyzed the sequence characteristics of hMSH2-specific TCR γδ cells. These CDR3δ clones were amplified by the hMSH2 protein and should be regarded as specific motifs that recognize hMSH2. According to these results, γδ T cells tend to utilize limited CDR3δ diversity to recognize specific protein ligands [53]. Studies have shown that after incubation with HSP60, the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) was increased in γδ T cells. Nitric oxide (NO)-induced apoptosis of γδ T lymphocytes involves activation of caspase-9 and the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, which is a strategy adopted by tumor cells to escape the immune recognition of γδ T cells [69]. Our team demonstrated that γδ T cells in peripheral blood could recognize hMSH2 expression on the tumor surface via the TCR and NKG2D. The results of our study demonstrated for the first time that hMSH2 expression on Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-transformed B cells is upregulated and participates in T cell-mediated antiviral cytotoxicity [70].

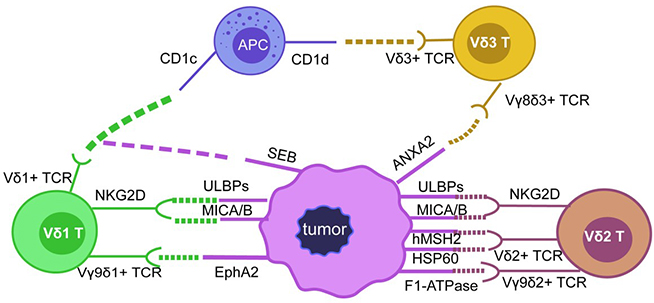

The above discussion indicates that the number of tumor-associated protein antigens recognized by γδ T cells is not very large, but many studies have demonstrated that γδ T cells play an important role in antitumor immunity. The identification of more protein ligands is significant to further clarify the interaction between γδ T cells and tumor cells (Figure 1).

Protein ligands involved in mediating cancer cell recognition via γδ TCR. The diversity of γδ T cells is mainly determined by the diversity of γδ TCR. Vδ1 T cells can recognize CD1c, EphA2 protein ligands through Vδ1+TCR and can be activated by SEB, and they can recognize ULBPs or MICA/B proteins through NKG2D receptors; Vδ2 T cells can recognize ULBPs and MICA/B through NKG2D, Vδ2+TCR can also recognize and bind hMSH2, HSP60, F1-ATPase and ANAX2 proteins to activate Vγ9δ2 T cells; there are not many studies reported about the ligands recognized by Vδ3 T, but Vδ3+TCR can recognize CD1d and ANXA2 protein ligands

Roles of γδ T cell recognized protein ligands in tumorigenesis and tumor development

In addition to acting as protein ligands recognized by γδ T cells to induce immune responses in the immune system, these protein ligands also have different roles in tumorigenesis and tumor development, which provides more possibilities for the utilization of γδ T cells in tumor immunotherapy. MICA/B was once thought to act as a “kill me” signal when cells are stressed, damaged or transformed and to mediate T cell cytotoxicity through NKG2D receptors [26]. However, recent studies have shown that the expression of MICA/B in normal tissue cells is more extensive, and only some epithelial cells and tumor cells express MICA/B on the cell surface [71]. NK cells can recognize ULBP proteins through the NKG2D receptor and kill tumor cells. Soluble ULBP proteins have been reported to provide a potential mechanism for gastric cancer cells to escape NKG2D-mediated immune cell attacks through downregulation of NKG2D expression [72].

ANXA2 plays a key role in heparin-binding epidermal growth factor (HB-EGF) exfoliation and IL-6 secretion in breast cancer cells. ANXA2 has been shown to mediate the progression of HER-2-negative breast cancer through the autocrine activity of HB-EGF and IL-6 [73]. At the same time, ANXA2 can be used as a potential target for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. In a human breast cancer xenotransplantation model, destruction of ANXA2 protein function can inhibit neovascularization in vitro and in vivo, thus preventing tumor progression [74]. EphA2 has been reported to be an extracellular vesicle (EV) biomarker for pancreatic cancer, distinguishing pancreatic cancer patients from pancreatitis patients and healthy subjects through NPES detection of EphA2-EVs [75]. EphA2 secreted by small EVs (sEVs) of senescent cells can bind to Ephrin-A1 and promote cell proliferation through EphA2/Ephrin-A1 reverse signaling [76].

HSP60 is highly expressed in colon cancer, pancreatic cancer, gastric cancer and other tumor cells and may be a biomarker for cancer diagnosis and prognosis [77]. As one of the important downstream molecules of insulin-like growth factor binding protein 7 (IGFBP7), downregulation of HSP60 can enhance the tumor inhibitory effect of IGFBP7 on colorectal cancer cells [78]. In addition, HSP60 can stimulate the production of ROS and enhance TNF-α-mediated apoptosis by interacting with the hepatitis C virus (HCV) core protein in human hepatocellular carcinoma Huh-7 cells [79]. At the same time, HSP60 can also promote the survival of cancer cells by inhibiting intracellular protein agglutinin in neuroblastoma cells [80]. Therefore, HSP60 cooperates with antitumor cells or effector molecules to inhibit the growth of tumors and can promote the occurrence and development of tumors. Further exploration is needed for its application in tumor immunotherapy. Studies have shown that high expression levels of MSH2 correspond to the worst survival rate in gastric cancer (GC), indicating that high intratumoral heterogeneity leads to resistance to GC treatment [81]. Alterations in MSH2 expression have been detected in sporadic colon tumors, indicating its role in the occurrence of colorectal tumors without genetic components. However, in the study, no correlation was found between MSH2 protein expression and the clinicopathological characteristics of patients [82].

These protein ligands of γδ T cells play different roles in tumorigenesis and tumor development. Whether they assist tumor cells in achieving immune escape or strengthen surveillance requires further investigation to determine their functions.

Therapeutic opportunities brought by tumor-associated proteins recognized by γδ T cells

Reports indicate that a new type of allo-human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-restricted and CD8α-dependent Vγ5Vδ1 TCR has been identified, and the classic anti-HLA-directed γδ TCR-mediated immune response can selectively act on blood and solid tumor cells in vivo and in vitro [83]. Bortezomib can significantly increase the expression of ULBP proteins in acute myeloid leukemia cells, thereby enhancing the killing of tumor cells by γδ T cells [84]. Vδ1T cells are known to recognize CD1c in the absence of specific foreign antigens, and CD1-restricted γδ T cells can mediate the maturation of dendritic cells for tumor antigen presentation [85]. CMV-induced non-Vγ9Vδ2T cells have specific clonal amplification and phenotypic characteristics and have demonstrated an effector function against CMV. The γδ T cell protein ligand ANXA2 expressed under stress conditions can activate these non-Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, which has introduced a new avenue for non-Vγ9Vδ2 T cell therapy in immunocompromised patients [86].

On the one hand, γδ T cells can mediate the lysis of tumor cells by recognizing HSP60 [66]. On the other hand, our team observed that chaperonin containing TCP1 subunit 5 (CCT5), a member of the HSP60 family, can inhibit the activation of γδ T cells by stimulating the secretion of Th2 cytokines in PBMCs in vitro, thereby avoiding an excessive peripheral immune response. The induced overexpression of hMSH2 by EBV-associated B-cell malignancies under stress conditions may be a marker for early tumor development and a potential target for γδ T cells for immunotherapy against EBV infection-related diseases. At the same time, our lab showed that oxidative stress induced ectopic expression of hMSH2 on human renal carcinoma cells. Under oxidative stress, the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathways have been shown to mediate the ectopic expression of hMSH2 through both the ectopic expression of apoptotic signaling kinase 1 (ASK1) upstream and activation of transcription factor 3 (ATF3) downstream of the pathway. In addition, IL-18 derived by renal cell tumor cell is an important factor significantly stimulated in oxidative stress for ectopic induction of hMSH2 expression, while IFN-γ also promotes this process. Finally, oxidative stress or pretreatment with IL-18 and IFN-γ enhanced γδ T cell-mediated lysis of renal cancer cells [87]. These results suggested that hMSH2 may enhance the cytotoxic activity of γδ T cells against human renal carcinoma cells, the activation and degranulation of γδ T cells and the secretion of the antitumor cytokines IFN-γ and TNF-α. Our laboratory has proposed a model based on the above studies that many protein ligands are only expressed intracellularly in normal healthy tissue cells and do not appear on the cell membrane, but in the presence of oxidative stress, these protein ligands are ectopically expressed on the surface of tumor cells and thus recognized by γδ T cells. However, the recognition mechanism of each protein ligand has not been verified one by one.

As mentioned above, our laboratory confirmed that Vγ9δ2 TCR recognizes tumor antigens through the CDR3δ region. We synthesized OT3, a CDR3δ peptide from tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) from ovarian epithelial carcinoma (OEC). We constructed full-length human PBMC-derived γ9 and δ2 chains, in which the CDR3 region was replaced by an OEC-derived peptide OT3. We transferred CDR3δ-grafted γ9δ2 TCRs into peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) to develop modified γ9δ2 cells. The experimental results showed that these CDR3δ-grafted γ9δ2 T cells were able to produce cytokines upon stimulation and exhibited cytotoxicity against tumor cells, including human OEC and cervical adenocarcinoma. In nude mice with human OEC cell lines, CDR3δ-grafted γ9δ2 T cells showed significantly stronger antitumor effects [88]. Meanwhile, our team verified that TCRγ4δ1-engineered αβT cells exhibited significant antitumor activity in vitro and in vivo. We amplified full-length TCRδ1 with GTM sequence from cDNAs of gastric cancer tissues and TCRγ4 chains from cDNAs of gastric tumor-derived γδ TILs, which were then cloned into pREP9 and pREP7 vectors for sequence analysis. We found that TCRγ4δ1-engineered αβT cells exhibited significant cytotoxicity against HepG2 and BGC-803 tumor cells and were validated on mouse tumor models [89].

The different effects of the interaction between these protein ligands and γδ T cells in the tumor microenvironment provide many possibilities for the application of γδ T cells in tumor immunotherapy.

Conclusions

γδ T cells play an important role in the anti-tumor immune response, especially their non-specific killing effect on tumors and their roles in immune surveillance in vivo are valued [73]. Identification of additional ligands recognized by γδ T cells has been a bottleneck in related research, and the current knowledge of the antigen recognition mechanism for γδ T cells and how γδ T is activated is still limited. However, recent studies have shown that γδ T cells infiltrate in the microenvironment of various tumor tissues and exert cytotoxic activity against tumor cells, suggesting that γδ T cells are critical in anti-tumor immunity in vivo [74]. In order to rationally utilize γδ T cells and their ligands for cancer immunotherapy, it is therefore necessary to reveal the tumor-associated protein ligands they recognize and clarify their roles in tumorigenesis development. Currently, there are few clinical approaches for γδ T cell use in tumor immunotherapy. One strategy is to enhance the number and activity of γδ T cells in patients and enhance the therapeutic effect by stimulation and reperfusion after expansion in vivo or in vitro, where both autologous and allogeneic γδ T cells used for reinfusion are expanded in vitro and the challenge is to generate large numbers of activated γδ T cells. The method commonly used to expand and activate γδ T cells is to stimulate γδ T cells in vitro using zoledronic acid and IL-2 [75], but protein ligands recognized by γδ T cells themselves, such as CD1d, can also be used to expand and activate γδ T cells, and activated γδ T cells may have the ability to specifically recognize certain tumor antigens. Another approach is to modify γδ T cells by two different design strategies-TCR-T and CAR-T cells that integrate the advantages of other lymphocytes to construct genetically modified cells with multiple specific functions [76, 77]. Identification of γδ T cell protein ligands provide more possibilities for antigen selection by CAR-T cells and TCR-T, which increases the potential of γδ T cells in tumor opportunities for immunotherapy applications.

Abbreviations

| ANXA2: | annexin A2 |

| APCs: | antigen-presenting cells |

| BTN3A1: | butyrophilin 3A1 |

| BTNL-3: | butyrophilin-like 3 |

| CAR: | chimeric antigen receptor |

| CDRs: | complementarity-determining regions |

| EBV: | Epstein-Barr virus |

| EphA2: | ephrin type-A receptor 2 |

| EV: | extracellular vesicle |

| HCMV: | human cytomegalovirus |

| HMBPP: | (E)-4-hydroxy-3-methyl-but-2-ene pyrophosphate |

| hMSH2: | human MutS homolog 2 |

| HSP60: | heat shock protein 60 |

| IFN-γ: | interferon-γ |

| IL-4: | interleukin-4 |

| IPP: | isopentenyl pyrophosphate |

| MHC: | major histocompatibility complex |

| MICA: | major histocompatibility complex class I chain-related A |

| MR1: | major histocompatibility complex class I related molecules |

| NK: | natural killer |

| NKG2D: | natural killer group 2 member D |

| OEC: | ovarian epithelial carcinoma |

| pAgs: | phosphoantigens |

| PBMC: | peripheral blood mononuclear cell |

| SEB: | staphylococcal enterotoxin B |

| TCRs: | T cell receptors |

| Th1: | T helper 1 |

| TILs: | tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes |

| TNF-α: | tumor necrosis factor-α |

| ULBP: | UL16-binding protein |

| Vδ1: | δ-chain variable region 1 |

| ZOL: | zoledronic acid |

Declarations

Author contributions

CL wrote the manuscript. YX helped to edit the figure. HC, JZ and WH revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81972866, 31970843, 82071791 and U20A20374), Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Initiative for Innovative Medicine (2021-1-I2M-005 and 2021-1-I2M-035) and Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Basic Research Expenses (2018PT31052). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2022.