Abstract

Gamma delta lymphocytes (γδ T) sit at the interface between innate and adaptive immunity. They have the capacity to recognize cancer cells by interaction of their surface receptors with an array of cancer cell surface target antigens. Interactions include the binding of γδ T cell receptors, the ligands for which are diverse and do not involve classical major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules. Moreover, a variety of natural killer-like and fragment crystallizable gamma (Fcγ) receptors confer additional cancer reactivity. Given this innate capacity to recognize and kill cancer cells, there appears less rationale for redirecting specific to cancer cell surface antigens through chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) expression. Several groups have however reported research findings that expression of CARs in γδ T cells can confer additional specificity or functionality. Though limited in number, these studies collectively identify the potential of CAR-T engineering to augment and fine tune anti-cancer responses. Together with the lack of graft versus host disease induced by allogeneic γδ T cells, these insights should encourage researchers to explore additional γδ T-CAR refinements for the development of off-the-shelf anti-cancer cell therapies.

Keywords

Chimeric antigen receptor, gamma delta lymphocytes, adoptive cancer immunotherapyIntroduction

Gamma delta T lymphocytes (γδ T cells) are a unique subset of T lymphocytes that have gained traction in recent years as an immunotherapeutic platform. Exerting direct cytotoxicity against tumor targets, γδ T cells act as potent antitumor effectors in the context of several types of cancer [1]. Importantly, they also act as key modulatory cells, releasing activating cytokines, such as interferon-γ (IFNγ) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα), to initiate signaling cascades that mount an additional immune response. γδ T cells have been found in a number of solid tumor infiltrates, and have been correlated positively with prognosis [2]. Further, the γδ T cell receptor (TCR) functions independently of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC), suggesting γδ T cells might be able to serve as an allogeneic cell therapy [3].

Different γδ T cell subsets, most notably Vδ1 and Vδ2, also display unique properties that are attractive for immunotherapeutic use. Specifically, Vδ2 cells constitute the predominant circulating γδ T cell population in humans, generally pairing with the Vγ9-chain. Vγ9Vδ2 cells respond ubiquitously in a TCR-dependent manner to non-peptidic pyrophosphates, or phosphoantigens (pAgs), that are intermediatesin the mammalian mevalonate and microbial metabolic pathways [4, 5]. pAgs mechanism of action entails conformational changes to butyrophilin molecules BTN3A1 and BTN3A2 which result in Vγ9Vδ2 engagement [6, 7]. As these pAgs are typically upregulated during either cellular transformation or microbial infection, Vγ9Vδ2 cells serve as robustly expanding effector cells primed for innate immune responses. They are also able to become professional antigen-presenting cells (pAPCs) following antigen stimulation, conferring multidimensional immune activation and indirect antitumor activity [8]. On the other hand, Vδ1 cells are more limited in circulating numbers, residing principally in adult peripheral tissues such as the gut [9] and skin [10]. Unlike the Vγ9Vδ2 subtype, Vδ1 cells do not pair preferentially with a particular γ-chain, yielding a TCR with responsivity to a diverse range of ligands that include stress-induced self-antigens and CD1c-presented glycolipids [11, 12]. They naturally home to a variety of tissue sites, leading to the notion that they carry intrinsic tissue-resident properties beneficial to intratumoral tracking and survival. Vδ1 cells are also resistant to activation-induced cell death, suggesting an enhanced ability to persist and function long-term in vivo [13]. In comparison, other human γδ T cell subsets are relatively poorly characterized in terms of phenotype and function. Despite the rising interest in γδ T cell therapy, much about their metabolic profiles, trafficking, signaling and co-stimulation requirements, as well as memory differentiation and exhaustion continues to be poorly understood for most subsets. Understanding such properties is essential for effective immunotherapeutic enhancement.

Chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) have dominated the recent field of cellular immunotherapy as a promising breakthrough capable of effective control of chemotherapy refractory cancers. The best documented success of CAR-based therapy involves genetically engineering αβ T cells with a CD19-specific single chain variable fragment (scFv) for leukemic B-cell targeting, either a CD28 or 4-1BB endodomain for co-stimulation, and a CD3ζ endodomain recapitulating TCR signaling. Several groups have investigated the antitumor efficacy of discrete αβ T cell-based CAR engineering strategies in γδ T cells in the context of both hematological and solid tissue malignancies. However, while many of the therapeutically relevant characteristics of distinct γδ T cell subtypes remain poorly defined, their distinctive and tissue-specific properties raise the hypothesis that γδ-CAR-T cells may have unique contributions to cancer therapy distinct from their αβ-CAR-T-counterparts. Hence, γδ T-CARs may have different requirements for sustained cell activation, long-term survival and maintenance, and ultimately, efficacious therapeutic impact. There are a relatively small number of γδ T cell-specific CAR strategies; each strategy has attempted to address activation requirements through cellular engineering tested both in vitro and in pre-clinical mouse models. Here, we discuss these strategies in various γδ T cell populations and tumor contexts and evaluate their collective findings to speculate on the next steps in tumor-specific γδ T-CAR development. We aim to highlight some of the cellular properties and unique findings from these and other authors to provide a glimpse of the full scope of γδ T-CAR therapy and the gaps that remain in the field.

Second-generation CARs in γδ T cells

Several key studies have examined the antitumor efficacy of γδ T cells engineered with second-generation CARs directed towards a number of tumor-specific antigens in the context of both hematological and solid tissue malignancies (Table 1). Importantly, these reports all demonstrated that γδ T cells are capable of stable CAR expression, regardless of the gene transfer method, cell expansion protocol, or antibody scFv design [14–19]. They also showed that γδ T-CARs mediated antigen-dependent antitumor activity against their respective cancer targets both in vitro and in vivo similar to equivalent CARs expressed in αβ T cells in terms of short-term cytokine production (TNFα and IFNγ), proliferation, and cytotoxicity [14–19].

Summary of published studies related to CAR expression in γδ T cells

| Author | Gene expression | Cell population + expansion | CAR type | Targeting antigen | Cytokine production | Tumour targets | In vivo tumour model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deniger et al., 2014 [16] | SB transposon | Whole polyclonal PBMCs + K562 aAPCs (CD19, CD64, CD86, CD137L, IL-15) | Second-generation CAR (28ζ) | CD19 (B-ALL) | TNFαIFNγ | ▪CD19-EL4 (Mu T cell lymphoma)▪NALM-6 (Hu B-ALL) | NALM-6 xenografts in NSG mice |

| Themeli et al., 2013 [17] | Lentivirus | T cells derived from iPSCs + 3T3-CD19 aAPCs | Second-generation CAR (28ζ) | CD19 (B-ALL) | TNFαIFNγIL-2 | CD19-EL4 (Mu T cell lymphoma) | CD19+Raji Burkitt lymphoma (Hu)xenografts in NSG mice |

| Fisher et al., 2017 [19] | SFG retrovirus | Vδ2+ cells from CD56-depleted PBMCs + zoledronic acid | Second-generation CAR (28ζ)Third-generation DAP10 CCR | GD2 (NB) | TNFαIFNγ IL-2IL-4Granzyme B | ▪Kelly (Hu NB)▪SK-N-SH (Hu NB) ▪LAN-1 (Hu NB) ▪TC-71 (Hu Ewing sarcoma) ▪CT26-GD2 (Mu colonic carcinoma) | N/A |

| Harrer et al., 2017 [15] | RNA electroporation | ▪PBMCs + zoledronic acid or anti-CD3 (OKT-3)▪ MACS-isolated γ/δ+ T cells & CD8+ T cells + OKT-3 | Second-generation CAR (28ζ)Melanoma-specific αβ TCR | ▪MCSP (melanoma)▪Melanosomal gp100 (melanoma) | TNFαIFNγIL-2 | ▪T2A1 (Hu TXB hybridoma)▪Mel526 (Hu melanoma)▪A375M (Hu melanoma)▪Daudi (Hu T cell lymphoma) | N/A |

| Capsomidis et al., 2018 [14] | SFG retrovirus | PBMCs + zoledronic acid or concanavalin A | Second-generation CAR (28ζ) | GD2 (NB) | N/A | ▪SK-N-SH (Hu NB)▪LAN-1 (Hu NB)▪SupT1 (Hu lymphoblastic lymphoma) | N/A |

| Fisher et al., 2019 [31] | SFG retrovirus | PBMCs + zoledronic acid and IL-2 or anti-CD3 (OKT-3), anti-CD28 (28.2), and IL-2 | Third-generation CAR (CD28ζ)Third-generation CD28 CCRThird-generation DAP10 CCR | ▪GD2 (NB)▪CD33 (AML)▪ ErB2 (breast adenocarcinoma)▪CD19 (B-ALL) | TNFαIFNγ | ▪LAN-1 (Hu NB)▪MV4-11 (Hu AML) | N/A |

| Ang et al., 2020 [34] | RNA electroporation | PBMC + zoledronic acid and IL-2 electroporated following expansion | First-generation (ζ)Second-generation (27ζ or 28ζ)Third-generation (28ζ-bb-ζ) | NKG2D | N/A | ▪SW470 and HCT116 (colorectal)▪SKOV3 (ovarian) | N/A |

| Fleischer et al., 2020 [35] | HIV-1 lentivirus | PBMCs + zoledronic acid and IL-2 | Second-generation NSCAR (IL-2 SP + Myc tag)Second-generation NSCAR (IL-2 SP + CD8α hinge) | ▪CD5 (T cell malignancies)▪CD19 (B-ALL) | IFNγ | ▪Jurkat (CD19−CD5+ T cell lymphoma)▪Molt-4 (CD19–CD5+ T-ALL)▪697 (CD19+CD5– B-ALL) | N/A |

| Rozenbaum et al., 2020 [18] | MSGV retrovirus | PBMCs + zoledronic acid and IL-2 | Second-generation CAR (28ζ) | ▪CD19 (B-ALL) | IFNγ | ▪NALM-6 (Hu B-ALL)▪CCRF-CEM (T-ALL)▪Toledo (NHL)▪K562 (CML) | NALM-6 xenografts in NSG mice |

aAPCs: artificial antigen-presenting cells; PBMCs: peripheral blood mononuclear cells; IL-15: interleukin-15; DAP10: DNAX-activating protein 10; CCR: chimeric costimulatory receptor; B-ALL: B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia; N/A: not applicable; MCSP: melanoma-associated-chondroitin-sulfate-proteoglycan; NKG2D: natural killer group 2D

Different γδ T cells production techniques yield products with distinct memory immunophenotypes

In the αβ CAR-T field, it has been observed that efficacy correlates with the differentiation phenotype, wherein naive and central memory T cells show increased capacity for continued proliferation and maintenance [20, 21]. However, the memory phenotype and differentiation patterns of γδ T cells are not as clearly defined, with mounting evidence for γδ T cells having distinct memory categories [13, 22, 23]. γδ T cells have been shown to have a high degree of differentiation in the periphery rather than in the thymus, utilizing signals from their tissue-specific environments, and to have distinctive immunophenotypic memory marker expression and function, which remain relatively poorly understood [24, 25]. Nevertheless, γδ T cell memory and immunophenotypes are still generally described using αβ T cell-based marker paradigms.

In one of the first published reports of a γδ T-CAR, Deniger et al. [16] evaluated the antileukemic capacity of a CD19-directed CAR expressed in a polyclonal population of γδ T cells. Briefly, they expressed a second-generation CD28ζ CAR in peripherally derived human γδ T cells using a Sleeping Beauty (SB) transposon-based gene transfer method, and expanded the whole population of mixed δ-chain repertoires using aAPCs engineered to engage with the CAR through surface expression of the CAR target antigen. Expanded CAR+ γδ T cells expressed high levels of memory markers associated in αβ T cells with naive/undifferentiated state, including CD27, CD28, CD62L, CCR7 and CD45RA. The CAR+ γδ T cells also expressed CD137 (4-1BB), an important co-stimulatory receptor, as well as cutaneous lymphocyte andigen (CLA), and chemokine receptor CXCR4, both associated with homing to bone marrow. The authors suggested that CAR+ γδ T cells generated using this method might have a proportion of naive-like cells that have the ability to migrate to tumor sites, a contention supported by in vivo data using the NALM-6 B cell leukemia mouse model. Notably, they observed control of tumor burden after 23 days with three doses of CAR+ γδ T cells combined with recombinant human IL-2.

In a seminal work on generation of off-the-shelf therapeutic CAR-T cells from αβ T cell-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), Themeli et al. [17] investigated a CD19-specific second-generation CAR (19-28ζ). Although these cells expressed an endogenous αβ TCR, the mRNA expression profile of 19-28ζ-T-iPSCs most closely clustered with freshly isolated and 7-day expanded blood-derived γδ T cells. They detected pronounced expression of CCL20, TNFSF11 (RANKL), CXCR6, and RAR-related orphan receptor C (RORC) genes amongst others that clustered with γδ T cell transcriptome, and found that the majority of 19-28ζ-T-iPSCs CD3+ cells had a CD45RA+CD62L–CCR7– effector memory phenotype, while a small proportion had a more naive CD45RA+CD62L+ phenotype. Notably, they did not detect expression of CD27 or CD28 receptors on 19-28z-T-iPSCs. However, the 19-28z-T-iPSCs did upregulate the natural cytotoxicity receptors natural killer protein 44Kda (NKp44), NKp46, and NKG2D and downregulate RORC, consistent with a cytotoxic and IFNγ producing γδ T cells phenotype, following in vitro expansion, irrespective of memory subset.

Testing whether these γδ-like CAR-T cells could functionally promote antitumor activity, they compared in vivo anti-tumor capacity of expanded 19-28ζ-T-iPSC cells, 19-28ζ-γδ T cells, and 19-28ζ-αβ T cells, respectively in a Raji B cell lymphoma xenograft model. Interestingly when phenotyping injected expanded cells, 19-28ζ-αβ T cells showed typical representation of all four classical memory subsets whilst both 19-28ζ-T-iPSC cells and 19-28ζ-γδ T cells were devoid of classical markers CD27, CD28 and CCR7. 19-28ζ-T-iPSC cells and 1928z-γδ T cells both delayed tumor progression to a similar extent but neither cell type was able to induce complete tumor regression, unlike 19-28ζ-αβ T cells. Whilst both Deniger and Themeli studies of second-generation γδ T CARs demonstrated enhanced antigen-targeted antitumor activity, they observed different γδ T cell phenotypes following expansion (Deniger et al. [16], predominant naive-like, central memory; Themeli et al. [17], differentiated effector-like) and this could be attributable different expansion methods; with additional costimulation and IL-2 and IL-21 in the Deniger method, whilst Themeli expanded with IL-7 and IL-15. Supporting this notion, Capsomidis et al. [14] compared memory phenotype (CD27 and CD45RA) in GD2-28-ζ CAR-transduced Vδ1 and Vδ2 cells expanded either with Concanavalin A, IL-2, and IL-4, or with zoledronic acid and IL-2, respectively. Using conventional αβT nomenclature, they found that expanded and transduced Vδ1 cells were either naïve or terminal effector memory, whereas corresponding Vδ2 cells were predominantly effector memory cells. Yet, both CAR+ cell types demonstrated antigen-specific proliferation and tumor migration in vitro.

Taken together, regardless of the memory phenotype, CAR+ γδ T cells undoubtedly exhibit potent cytotoxicity in vitro and in vivo, although more differentiated cells appear to be unable to maintain tumor control to the same extent as their αβ-counterparts in long-term studies. Thus, we argue that further elucidation of γδ T cell memory phenotype, its functional implications long-term in vivo, as well as the role of expansion and co-stimulation, is required for γδ T CAR enhancement.

Exhaustion

T cell exhaustion, defined as hypofunctional state associated with expression of inhibitory receptors, is the subject of intense research interest in αβ T cells [26–29] but with limited published information in γδ T cells [30–33]. Notwithstanding, several studies have evaluated expression of canonical exhaustion markers in CAR-expressing γδ T cells. Fisher et al. transduced expanded αβ T cells and γδ T cells (primarily Vδ2+), respectively, with a GD2-28-ζ CAR and assessed the concomitant expression of programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) and T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 3 (TIM-3) after 16 days of culture with IL-2. Both cell types displayed increased proportions of PD-1+Tim-3+ cells compared to their untransduced counterparts, and similar levels compared with each other, suggesting the CAR itself might play a role in promoting T cell exhaustion. Further substantiating this claim, the same authors demonstrated that the second-generation CARs lead to tonic signaling (intracellular activation in the absence of antigen) that results in a diminished capacity to remodel signaling networks in response to new stimuli—essentially, an “exhausted” phenotype— in both αβ T and Vδ2+ γδ T cells [31]. Similarly, Capsomidis et al. [14] showed that transduction with the GD2-28-ζ CAR led to increased expression of PD-1 and TIM-3 in αβ T and Vδ2+, but not Vδ1+ cells, even in the absence of cognate antigen.

Collectively, these findings suggest that certain populations γδ T cells, specifically Vδ2+, may be susceptible to CAR-induced T cell exhaustion analogous to αβ T cells, especially when expressing a tonically signaling second-generation CAR. The observation of reduced CAR associated exhaustion marker expression in Vδ1+ cells is encouraging for further evaluation of Vδ1+ cells in CAR-T cell therapy. More work needs to be done to clarify whether these cells can become functionally exhausted, the reversibility of such a state, and the markers expressed when that happens. It does, however, lend to the notion that second-generation CARs might not be the optimal gene engineering strategy to harness γδ T cells for cancer immunotherapy.

CCRs

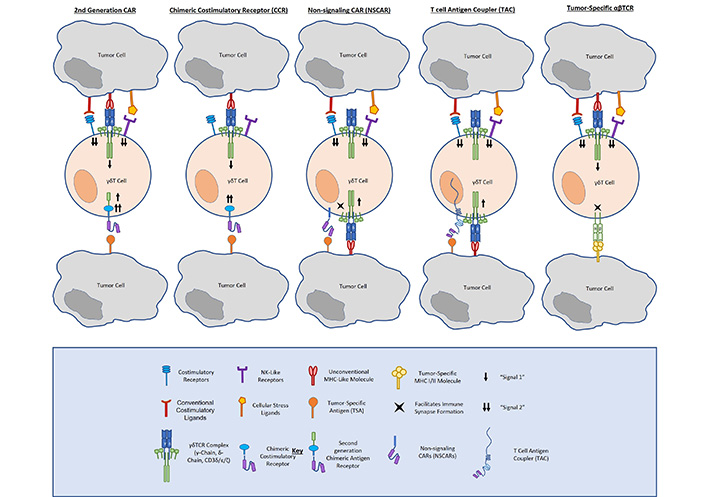

Unlike conventional CARs, CCRs incorporate an antibody-binding (scFv) and costimulatory (CD28, 4-1BB, DAP10, NKG2D, etc.). domain without an ITAM-containing signaling domain, such as CD3ζ. In this way, CCRs confer enhanced tumor-specific costimulation to γδ T cells, providing enhanced tumor antigen-dependent activation, whilst preserving native TCR function and specificity. Because they depend on endogenous γδ TCR activation, CCRs offer the same tumor-targeting advantages as do γδ T cells. Specifically, γδ TCRs function independently of MHC-binding, enabling them to recognize a number of tumors utilizing immune evasive mechanisms. The γδ TCR also innately recognizes cellular stress ligands that are not expressed on healthy tissue, allowing them to provide natural on-target, on-tumor cytotoxicity and natural avoidance of reactivity to non-malignant cells (Figure 1).

Fisher et al. [19] described a neuroblastoma-targeting CCR that incorporates natural killer receptor (NKR) costimulation in γδ T cells (i.e., GD2-DAP10). Comparing a GD2-28ζ CAR and a GD2-DAP10 CCR expressed in Vδ2+ cells, respectively, they demonstrated that CCR-expressing cells exerted a cytolytic response and released inflammatory cytokines similarly to CAR-expressing cells. Importantly, they found that full cytotoxicity and cytokine release occurred only when both the endogenous TCR (signal 1) and the CAR (signal 2) were engaged, but not when either is engaged alone. They also asserted that Vδ2-CCRs expressed lower frequencies of the exhaustion markers PD-1 and TIM-3 than did Vδ2-CARs, arguing for the long-term survival advantages of CCRs in γδ T cells.

In later studies, Fisher et al. [31] analysed CCRs comprised of a range of tumor-specific antigens (e.g., GD2, CD33, and CD19) and incorporate either TCR-mediated (i.e., CD28) or NKR-mediated (i.e., DAP10/NKG2D) costimulation. Evaluating cytotoxicity and cytokine release, all of their tested CCRs were capable of mediating cytolysis and producing TNFα and IFNγ in response to antigen-expressing tumors, but not healthy cells. However, when exploring downstream signaling strength, DAP10 yielded the most robust response. Not only did the GD2-DAP10 CCR incite the most potent TNFα production, but it also supported increased cell network plasticity wherein cells were able to flux between different signaling pathways, suggesting its utility in allowing sustained cell responsivity over time. Although more work is needed on the costimulatory needs for persistent function and maintenance in γδ T cells, the conclusion from this work is that CCRs pose a promising format of gene engineering in γδ T cells.

First-generation CARs, non-signaling CARs and T-cell antigen couplers

While the strategies discussed above yield γδ T cells with enhanced cytotoxic capacity against cancer, other approaches have aimed to direct γδ T cells towards tumor targets without providing costimulation to prevent tonic CAR signaling. First-generation CARs provide the tumor-targeting scFv antibody-binding domain and CD3ζ signaling domain of a second-generation CAR without any T cell costimulatory domain. Importantly, Ang et al. [34] demonstrated that Vγ9Vδ2 cells electroporated with an NKG2D-specific first-generation RNA CAR exhibited cytotoxicity against multiple human solid tumor cell lines. Further, these cells were able to delay disease progression in tumor-bearing mice. While these results are encouraging for the use of a first-generation CAR in γδ T cells, there are several points to be addressed in its therapeutic development. The authors postulated that the transient nature of electroporated RNA expression would help prevent on-target/off-tumor toxicity. Although it was not examined in their work, such a design could potentially abate the concern for T cell exhaustion; however, it would require multiple injections for sufficient disease treatment, as demonstrated by their xenograft data.

As another means of addressing tonic signaling associated with traditional CARs, non-signaling CARs remove all activation endodomains from a chimeric receptor and anchor a tumor-targeting scFv to a transmembrane domain (Figure 1). Like CCRs, non-signaling CARs (NSCARs) utilize the innate function of the γδ TCR to engage with stress ligands expressed on tumor cells and provide an additional tumor-homing signal on the cell surface. Fleischer et al. examined the cytotoxicity of CD5– and CD19-directed NSCARs in γδ T cells [35]. Testing them against CD5+ Jurkat and Molt-4 cell lines, as well as CD19+ 697 cells, they showed that NSCARs could confer enhanced cytotoxicity to antigen-expressing targets in vitro.

In a similar vein, one group has mounted γδ T cells with a tumor-targeting scFv bound to a CD3ɛ-binding antibody domain and a CD4 hinge, transmembrane, and cytosolic tail. These T-cell antigen couplers (TACs, Figure 1) redirect T cells towards tumor antigens, but rely on native TCR-ligand binding for full activation and costimulation [36]. This group first showed TAC function and efficacy targeting both human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) and CD19 in αβ T cells. Comparing TACs to their corresponding second-generation CD28ζ and 4-1BBζ CARs, respectively, they showed that TACs did not upregulate exhaustion markers or promote T cell terminal memory differentiation to the same extent as CARs. The TACs were also able to mediate potent anticancer efficacy against solid and liquid tumor models. Most notably, HER2-TAC-T cells showed enhanced antitumor activity and tumor penetration against a solid tumor model as compared to the second-generation HER2-CAR. The same group have gone on to examine TAC function and antitumor efficacy when expressed in γδ T cells. In a brief report, they asserted that TACs induced tumor cytotoxicity in vitro and in vivo in γδ T cells, arguing for further development as a solid cancer treatment [37].

While both NSCARs and TACs show promise as a successful means of tumor tethering, much remains to be determined about their therapeutic efficacy, especially their longevity without the addition of other TCR signals and their tumor trafficking and anticancer activity in vivo when expressed in γδ T cells. Additionally, much like traditional first and second-generation CARs, both NSCARs and TACs rely on the presence of tumor-specific antigens for targeting. A novel tethering strategy recently published involves γδ TCR anti-CD3 bispecific molecules (GABs) that combine the tumor targeting capacity of an extracellular Vγ9Vδ2 TCR domain with the activating pan-CD3 scFv OKT-3 [38]. Using this method, van Deist et al. found that GABs were able to redirect αβ T cells towards hematologic and solid tumor cell lines, as well as primary patient-derived tumor cells. Moreover, treatment with these GABs in myeloma xenograft models yielded a significant reduction in tumor growth. Thus, GABs represent another promising route towards an effective γδ-mediated tumor metabolite immunotherapy against a broad range of cancers.

Transduced αβ TCRs

As an alternative approach for enhancing γδ T cell tumor targeting and activation, transducing γδ T cells with a tumor-specific αβ TCR has been explored. In one key study, van der Veken et al. [39] transduced γδ T cells with a leukemia-specific αβ TCR to implement tumor specificity to an effector population capable of robust killing and cytokine production without mixed TCR dimerization. They showed that transduction with an HA-2-specific αβ TCR conferred γδ T cells with potent anti-leukemic activity [39]. Similarly, Hiasa et al. [40] showed that γδ T cells transduced with an MAGE-A4-specific CD8+ αβ TCR acquired cytotoxicity against antigen-expressing tumor cells and produced cytokines in both αβ- and γδ-TCR-dependent manners. More recently, Harrer et al. [15] showed successful RNA transfection of γδ T cells with a melanoma-specific αβ TCR, whereby receptor-transfected cells exhibited melanoma-specific lysis while also retaining intrinsic γδ cytotoxic activity. Such a strategy is appealing, as it allows for patient-derived tumor targeting, but ongoing work is required to elucidate its safety and efficacy.

Gene transfer of γδ TCRs

Another appealing approach to provide γδ-mediated therapeutic benefit targeting tumor targets involves transducing canonical αβ T cells with a γδ TCR. In this way, highly proliferative effector lymphocytes, readily attainable in high numbers from a single donor, acquire both the broad tumor reactivity and healthy self-protection of a γδ TCR without the need for a particular tumor-specific antigen. As demonstrated by Kuball and researchers, αβ T cells can efficiently express a Vγ9Vδ2 TCR that redirects them against cancer with tumor-specific proliferation and effector function [41]. One caveat to note in their study is the need for bisphosphonate application for maximal in vivo efficacy of transduced cells. However, Strijker et al. [42] showed that Vγ9Vδ2-expressing αβT cells were competent at killing neuroblastoma organoids independent of MHC-I expression. Further, these γδ-engineered αβ T cells demonstrated superior effector function compared to donor-matched untransduced αβ T and γδ T cells, respectively, suggesting preliminarily therapeutic promise for this method.

Conclusions

Altogether, we assert that γδ T cells serve as an up-and-coming therapeutic product. Whether as a platform for CAR-T cell therapy or for any of the alternative CAR developments, γδ T cells provide a robust effector cell with the ability to home to tumor sites, infiltrate, and exert tumor-specific cytotoxicity with concomitant cytokine production. However, as we have highlighted here, much remains to be evaluated in these cells, including exhaustion, memory phenotype and differentiation, as well as costimulation requirements. Understanding these properties both in natural γδ T cells and in transduced γδ T cells will allow for further advancements in therapeutic designs for optimal tumor targeting. In addition to this incomplete knowledge on therapeutically relevant properties within γδ T cells, γδ T-CAR development has also been confined by the limited application to human patients. The studies described here, while valuable to the field, have only addressed antitumor function in contrived cell co-culture and in pre-clinical mouse models. However, there have been a number of γδ-based immunotherapy clinical trials that supported the use of allogeneic γδ T adoptive cell transfer in cancer treatment. Several completed trials have demonstrated safe and efficient administration of γδ T cells against breast (NCT03183206), liver (NCT03183219), lung (NCT03183232), and pancreatic (NCT03180437) cancers, respectively. Further, ex vivo expanded γδ T cells have been approved in ongoing phase 1 trials against hepatocellular carcinoma (NCT04518774) and acute myeloid leukemia (NCT05015426, NCT05001451), while CAR-engineered γδ T cells targeting NKG2D ligand (NKG2DL) are being examined against relapsed or refractory solid tumors (NCT04107142). Thus, γδ T cells provide a promising platform for the future of cell-based cancer immunotherapy.

Abbreviations

| aAPCs: | artificial antigen-presenting cells |

| B-ALL: | B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia |

| CARs: | chimeric antigen receptors |

| CCR: | chimeric costimulatory receptor |

| DAP10: | DNAX-activating protein 10 |

| GABs: | γδ T cell receptor anti-CD3 bispecific molecules |

| γδ T cells: | gamma delta T lymphocytes |

| HER2: | human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 |

| IFNγ: | interferon-γ |

| IL-15: | interleukin-15 |

| iPSCs: | induced pluripotent stem cells |

| MHC: | major histocompatibility complex |

| NKG2D: | natural killer group 2D |

| NSCARs: | non-signaling chimeric antigen receptors |

| pAgs: | phosphoantigens |

| PBMCs: | peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

| PD-1: | programmed cell death-1 |

| scFv: | single chain variable fragment |

| TACs: | T-cell antigen couplers |

| TCR: | T cell receptor |

| TIM-3: | T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 3 |

| TNFα: | tumor necrosis factor-α |

Declarations

Author contributions

GMF and JA shared equally in design and writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read and approved the submitted version.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

John Anderson receives funding from the NIHR Great Ormond Street Biomedical Research Centre and Gabrielle M. Ferry is in receipt of a PhD studentship funded by TC-Biopharm. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2022.