Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a common neurological disease in the elderly, and the major manifestations are cognitive dysfunction, neuronal loss, and neuropathic lesions in the brain. In the process of AD pathogenesis, the inflammatory response plays an indispensable role. The nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome containing NOD, leucine-rich repeat (LRR), and pyran domains is a multi-molecular complex that can detect dangerous signals related to neurological diseases. The assembly of NLRP3 inflammasome promotes the maturation of interleukin-1beta (IL-1β) and IL-18 mediated by caspase-1 in microglia, which leads to neuroinflammation and finally contributes to the occurrence and development of AD. This review aimed to clarify the structure and activating mechanism of NLRP3 inflammasome and its key role in the pathogenesis of AD, summarize the latest findings on the suppression of NLRP3 inflammasome activation for the treatment of AD, as well as indicate that targeting regulation of NLRP3 inflammasome assembly may be a potential strategy for the treatment of AD, providing a theoretical basis for the research of AD.

Keywords

Alzheimer’s disease, NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 inflammasome, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase-1 recruitment domain, caspase-1, β-amyloidIntroduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), also known as dementia, is the most common type of dementia in the elderly. The main pathological features of AD include amyloid β-protein (Aβ) deposition in extracellular senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles formed by excessive phosphorylation of tau protein, as well as neuron loss with glial cell proliferation [1]. AD is mainly manifested as memory disorders, cognitive dysfunction, language disorders, etc., which seriously affect people’s normal life and physiological functions [2]. Besides, the pathophysiology of AD is quite complex and involves multiple pathogenesis mechanisms such as apoptosis, inflammation, as well as oxidative stress, in which inflammation is one of the key factors in the pathophysiology of AD [3]. Microglia play an indispensable role in the inflammatory response, where the activation and proliferation of microglia concentrated around senile plaques are remarkable features of AD, and activated microglia could be harmful to neurons [4]. Microglia can clear different types of Aβ, but the sustained interaction of these cells with Aβ can cause an inflammatory response, which leads to neurotoxicity. Moreover, Aβ could promote the formation and activation of nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome in microglia [5]. Activation of inflammasomes in microglia results in caspase-1 (CASP1) maturation and releases interleukin-1beta (IL-1β) and IL-18, which plays a pathogenic role in AD [6]. Thus, inhibition of neuroinflammation is a promising remedial strategy to moderate or delay AD pathology [7].

NLRP3 is a cytoplasmic protein that is an inflammatory signaling complex formed on stimuli associated with injury [8]. NLRP3 is a key component of macrophage-mediated immune and inflammation regulators, and a key inflammatory signaling platform for initiating innate immune responses. It can respond to various stimuli and play a crucial role in innate immunity [9]. There is mounting evidence suggesting that NLRP3 inflammasomes were involved in many diseases, including AD, stroke, type 2 diabetes, arthritis, asthma, Parkinson’s disease and so on [10–14]. It is particularly important that the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome and microglia, as well as the release of inflammatory cytokines like IL-1β and IL-18, played a significant role in neurodegenerative diseases [15].

This review summarized the structure and the mechanism of NLRP3 inflammasome upon activation, and its potential role in AD. Besides, inhibitors against NLRP3 and NLRP3-related pathways hopefully for AD treatment were introduced.

Structure and activation mechanism of NLRP3 inflammasome

The formation of NLRP3 inflammasome

Innate immunity recognizes pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMP) as well as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMP) via pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) by removing pathogens or impaired host cells thus restoring damaged tissues. PRRs were comprised of toll-like receptors (TLRs), retinoic-acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I)-like receptors (RLRs), NOD-like receptors (NLRs), etc. PRRs could activate downstream signal transduction pathways, as well as mediate immune response after activation. NLRs activation could also lead to the formation of inflammasome, thus resulting in inflammatory response [16, 17]. NLRP3 contains leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain, intermediate NOD domain, and amino-terminal (N-terminal) thermo protein domain—pyridine domain (PYD). Apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase-1 recruitment domain (ASC) is a combination of caspase recruitment domain (CARD) and PYD. NLRs were an evolutionarily conserved family of cytoplasmic receptors with a tripartite structure, where they have a mutual central nucleotide binding and oligomerization domain (NACHT), a C-terminal LRR sequence domain, and an N-terminal effector PYD or CARD [18]. NLRs could recognize various stimuli and terminate self-suppressing state by LRR domain. Then a downstream adaptor ASC containing CARD could bind to the altered NLRs via homotypic CARD–CARD interactions and aggregate into multimers. Subsequently, CASP1 was recruited through CARD, resulting in CASP1 dimerization and activation. NLR is one type of PRRs [19, 20]. To date, many inflammasomes have been identified, including NLRP1, NLRP2, NLRP3, absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2) and NOD-like receptor C4 (NLRC4), with the most studied and most distinctive being the NLRP3 inflammasome [21].

The NLRP3 inflammasome was a multi-protein complex that included recognized signal molecule NLRP3, adaptor protein ASC, and effector protein pro-CASP1, which were key signaling mediators in inflammatory activation. The interaction among these proteins was strongly correlated to the function of the inflammasome. NLRP3 was mainly expressed in microglia and was related to multifarious inflammatory diseases, such as Aβ [22]. Recruitment of pro-CASP1 to ASC can promote the autocatalytic activation of CASP1, resulting in the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-1β and IL-18 [23, 24]. These secreted pro-inflammatory cytokines further promote the inflammatory response via binding to relevant cell receptors.

The activation of NLRP3 inflammasome

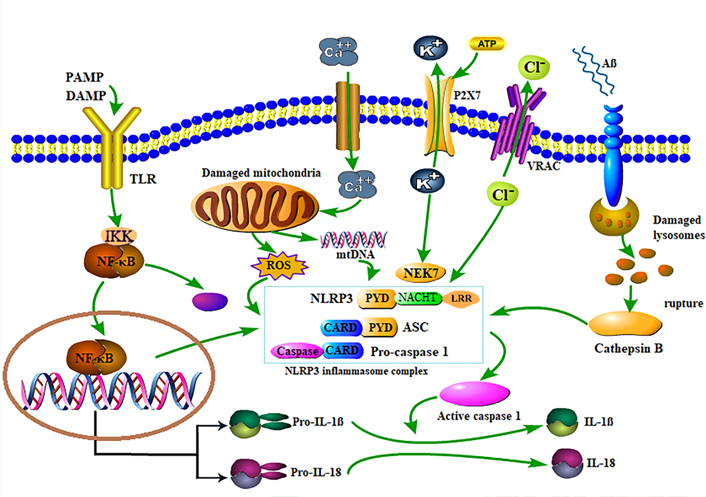

Two steps were involved in the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome. The priming step was to stimulate the NLRP3 inflammasome, in which PAMP or DAMP was recognized by TLR, leading to the activation of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB)-associated signaling pathway and in turn, up-regulated the transcription of inflammasome-relevant molecules. Activation of NF-κB promotes NLRP3, pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 transcription, providing the material basis for the activation and action of NLRP3 vesicles and reducing the activation domain of NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles. NLRP3 is post-translationally ubiquitinated but not oligomerized and is not active until the initiation signal activates the deubiquitinating enzyme BRCA1/BRCA2-containing complex subunit 3 (BRCC3) to deubiquitinate NLRP3 [25]. When the C-terminal LRR domain recognized PAMP or DAMP, the intermediate NOD domain-mediated self-oligomerization, and then the N-terminal PYD combined with ASC could raise CASP1 precursor, activate NLRP3 inflammasome, promote the activation and maturation of IL-1β and IL-18 [26]. Next, NLRP3, ASC, and pro-CASP1 were secreted and assembled into a complex and resulting in the cleavage of CASP1 and maturation of IL-1β and IL-18. Currently, there are several recognized upstream mechanisms for the inflammasome activation: releases of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS), synthesis of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), ion flux, phagosome instability due to lysosomal cathepsin release, and so on [27, 28] (Figure 1).

Schematic diagram of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. After exposure to PAMP or DAMP, TLR is phosphorylated, and IκB kinase (IKK) is activated, leading to IκB protein phosphorylation and ubiquitination, IκB protein degradation; NF-κB dimer is released to activate NF-κB, and thus promotes the assembly and activation of NLRP3 inflammasome, leading to proteolysis and pro-CASP1 activation to form active CASP1 dimers, thereby pushing pro-IL-18 and pro-IL-1β to IL-18 and IL-1β. Extracellular ATP can induce K+ efflux through P2X7-dependent pores, and the low K+ state in the cell promotes the binding of downstream never in mitosis A (NIMA)-related kinase 7 (NEK7) molecules and NLRP3, thereby mediating the activation of CASP1. Damaged mitochondria can release ROS and mtDNA, and ROS can promote the assembly and activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes, and mtRNA can promote the activation of CASP1, and calcium flux is also involved in these processes. At the same time, Cl– outflow through the volume-regulated anion channel (VRAC) is also conducive to the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome. The phagocytosis of Aβ results in lysosomal rupture and releases lysosomal content, such as cathepsin B, which induced the NLRP3 inflammasome assembly and activation. When NLRP3 inflammasome was activated, it catalyzed pro-CASP1 into CASP1, and thus facilitating the secretion and expression of mature IL-1β and IL-18

Production of mitochondrial ROS

Mitochondria are organelles that could coordinate energy production and metabolism as well as participate in biological processes such as inflammation and cell death. Mitochondria are sensitive to cellular stress, which will result in depolarization of the mitochondrial membrane and the release of ROS [29]. When mitochondria were damaged by stress, the mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) was damaged, resulting in a large amount of ROS release, NLRP3 inflammasome activation, and increased secretion of IL-1β and IL-18 [30, 31]. Increasing evidence demonstrated that thioredoxin (TRX)-interacting protein (TXNIP) is a key component of inflammation, and ROS mainly act on TXNIP, thereby activating NLRP3 inflammasome [32–34]. Nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) is a key regulator of TXNIP and keeps the basic expression of TXNIP at a low level [35]. After intraperitoneal injection of t-butyl hydroquinone (tBHQ, an agonist of Nrf2) into Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats, the expression of TXNIP, NLRP3 inflammasome and downstream factors such as CASP1, IL-1β and IL-18 in cytoplasm was significantly down-regulated, while Nrf2 knockdown suggested the opposite result [36]. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is the main membrane component of Gram-negative bacteria and is commonly used to induce inflammation [37]. After stimulation by LPS, BV-2 microglia promoted NF-κB intranuclear translocation and NLRP3 activation, and promoted the production of ROS and nitrogen monoxide (NO), as well as up-regulated the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and IL-1β [38]. Study has found that linarin (LR) inhibited LPS-induced oxidative stress and the release of proinflammatory cytokines by inhibiting proteins and NF-κB signaling pathways that interacted with TRX, including its downstream and upstream signals, such as NLRP3, ASC, CASP1, IKK-α, and IκBα. LR could reduce LPS-induced ROS and inhibited inflammation and oxidative stress of BEAS-2B in human lung epithelial cells [39]. In addition, Berberine (BBR) and mitochondrial superoxide dismutase mimetics (Mito-TEMPO), a specific mitochondrial ROS (mtROS) scavenger, significantly limited the activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes and increased the MMP, as well as reduced the production of mtROS in J774A.1 macrophages [40]. Activation of NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles is therefore closely linked to mtROS production. Inhibition of mtROS production or removal of mtROS can be achieved through a variety of pathways to inhibit NLRP3 inflammatory vesicle activation.

Ion flux

At present, more researched ion fluxes mainly include K+ efflux, Cl– efflux and Ca2+ signaling, which have been identified as key events in the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome [41]. Inhibition of K+ efflux and mitochondrial dysfunction has been reported to prevent NLRP3 activation [28, 42]. NEK7, a member of the mammalian NEK protein family, is an NLRP3 binding protein that functions downstream of K+ efflux and regulates oligomerization and activation of NLRP3 [43, 44]. Inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and pyroptosis was observed when NEK7 is knocked out [45]. Extracellular ATP as an agonist of NLRP3 can induce K+ efflux through the cation channel P2X7, leading to mitochondrial damage and ROS production and activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome [46, 47]. Furthermore, one important study found that tandem of pore-domains in a weakly inward rectifying K+ channel 2 (TWIK2) was a K+ efflux channel required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation. P2X7 receptor and TWIK2 act in cooperation to regulate the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome [48]. However, several small molecules, including imiquimod and CL097, promoted NLRP3 inflammasome activation independently of K+ efflux, but it required ROS, complex I dysfunction and NEK7 [49]. The above studies suggest that K+ efflux has an activating but not necessary effect on the NLRP3 inflammasome and may not have a direct role in relation to NLRP3.

VRAC, which regulated cell volume through transporting Cl– and all kinds of organic permeates throughout the plasma membrane, as well as mediated Cl– efflux during the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome [50]. The study by Daniels et al. [51] suggested that the pharmacological inhibition of VRAC activity could block the cationic current and subsequently activate the NLRP3 inflammasome. In addition, the chloride intracellular channel (CLIC) also mediated Cl– efflux during the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. A recent study found that CLIC could act on K+ efflux and downstream of ROS. ROS induce the transfer of CLICs to the plasma membrane to induce chloride outflow, thereby promoting NEK7-NLRP3 interactions and NLRP3 inflammasome assembly and activation, increasing expression of CASP1 and IL-1β [52].

Ca2+ could flow out of extracellular and intracellular storage and played a considerable role in activating NLRP3 inflammasome and accelerating mitochondrial damage during ATP stimulation, whereas preventing Ca2+ mobilization could repress the NLRP3 inflammasome formation and activation [53]. Lysosomal membrane permeabilization (LMP) triggers Ca2+ influx, attenuated Leu-Leu-O-methyl ester (LLME)-stimulated NLRP3 inflammatory corpuscle signaling, but enhanced LLME-induced necrosis [54]. The mouse calcium-sensitive receptor (CASR) activated the NLRP3 inflammasome by mediating an increase in intracellular Ca2+ and a decrease in cell cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). cAMP directly binds to NLRP3 to inhibit the assembly of inflammasome, while down-regulation of cAMP could alleviate this inhibition [55]. In addition, acid-sensitive ion channels (ASICs), G-protein-coupled receptor 43 (GPR43) and transient receptor potential melastatin-2 (TRPM2) all could activate NLRP3 by mediating Ca2+ [56–58]. The flow of ions is closely related to mitochondria and lysosomes. In addition to direct inhibition of NLRP3 inflammatory vesicle activation through inhibition of K+, Ca2+ and Cl– ion flow, NLRP3 inflammatory vesicle activation can also be stimulated through ion flow to mitochondria and lysosomes.

The synthesis of mtDNA

In addition to ROS and ion flux, mtDNA from damaged mitochondria also regulated the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome through the release of TLRs and pro-inflammatory cytokines. It is already known that NLRP3 activator triggers mitochondrial damage through plasma membrane ruptures, K+ effluxes and intracellular Ca2+ increases, resulting in the release of fragment mtDNA and ROS generation, which converts mtDNA into oxidized mitochondrial form (ox-mtDNA), and ultimately leading to NLRP3 activation [59–61]. For instance, in endothelial cells, mtDNA activated NLRP3 through mtROS release and Ca2+ influx [62]. In addition, exogenous LPS and ATP triggered K+ outflow, which leaded to the production of mtROS, promoted the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome, and released oxidized mtDNA into the cytoplasm [63]. The data from Shimada et al. [64] indicated that the cytoplasmic release of oxidized mtDNA and its binding to NLRP3 were beneficial to activating NLRP3 inflammasome, while oxidized nuclear DNA 8-OH-dG could competitively inhibit the binding of oxidation of mtDNA to the NLRP3 inflammasome and secretion of IL-1β. In addition, it was found that LPS drove the activation of MyD88 and the TIR domain-containing adaptor inducing interferon-β (TRIF)-dependent transcription factors interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF1) and NF-κB by binding to TLR4. While IRF1 drove the expression of the nucleoside monophosphate kinase cytidine/uridine monophosphate kinase 2 (CMPK2), CMPK2 transferred to mitochondria and enhanced the supply of deoxyribose nucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) for mtDNA synthesis. The oxidized mtDNA directly binded to NLRP3 to promote assembly of NLRP3 inflammasome and signal transduction, leading to IL-1β secretion and triggering inflammation [65]. The above results suggest that blocking the synthesis of mtDNA can be one of the effective means to inhibit the activation of NLRP3.

Lysosomal breakdown

In addition to the above activation signals, cathepsin B released from unstable lysosomes also promoted the activation of NLRP3. Crystals or aggregated NLRP3 activators such as Aβ can induce phagolysosomal disruption, resulting in lysosomal disruption, proteolysis, and cathepsin B release into the cell cytosol [66]. The cathepsin B is thought to be involved in the NLRP3 inflammasome activation and promote the formation of IL-1β [67, 68]. After treatment with different types of NLRP3 activators such as ATP, nigericin or crystals, cathepsin B interacted with NLRP3 at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) level, which subsequently leads to CASP1 activation [69]. H2O2 treatment increased the activity of cathepsin B in microglia, which in turn activated the NLRP3 inflammasome, and subsequently conversed pro-CASP1 into CASP1 and IL-1β secretion. The pharmacological inhibition of cathepsin B prevented the cleavage of pro-CASP1 to CASP1, and subsequently prevented the secretion of IL-1β induced by H2O2. Importantly, compared with the healthy control group, the levels of cathepsin B activity, IL-1β levels and malondialdehyde (MDA) in the plasma of AD patients were significantly increased, while glutathione was significantly lower than that of the healthy control group, indicating oxidative stress might activate NLRP3 by up-regulating cathepsin B activity [70]. In addition, the release of cathepsin B played an important role in the activation of NLRP3-CASP1 inflammasome induced by Mn, as well as promoted the accumulation of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-18 in BV-2 microglia [71]. Lysosomal catabolism produces enzymes that contribute to the activation of NLRP3 and may induce AD.

Possible roles for NLRP3 inflammasome in AD

With the current surge in dementia worldwide, there is an urgent need to work on a drug that can counter and slow down the progression of dementia. There are currently few drugs on the market for AD, and even fewer have been approved for marketing in recent years, leaving an unmet medical need. Current research in the treatment of AD is being devoted to the exploration of new targets.

The accumulation of Aβ outside cells is an important event in the pathogenesis of AD brain [72]. Aβ production and failure of Aβ clearance are key factors in the development of AD. Moreover, the accumulation of Aβ is closely related to the occurrence of neuroinflammation. Systemic inflammation can activate the TLR4 and NLRP3 inflammasomes in microglia, leading to neuroinflammation, the accumulation of Aβ, the loss of synapses and neurodegeneration in the brain [5, 73–75]. Previous studies had found that Aβ could activate NLRP3 inflammasome in microglia and astrocytes, and further leaded to the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and the occurrence of inflammatory events [76, 77]. Moreover, Aβ stimulation promoted the degradation of NF-kappa-B inhibitor alpha (IkBα) in microglia, up-regulated the expression of NF-κB phosphorylation, up-regulated the TXNIP/TRX/NLRP3 pathway, and promoted the expression of cleaved CASP1 and IL-1β [78]. There is also evidence that inhibition of NLRP3 largely ameliorates spatial memory loss and reduces Aβ deposition in mouse models of AD [79]. Halle et al. [80] reported that the NLRP3-CASP1 pathway was activated after Aβ phagocytosis, resulting in lysosomal damage, cathepsin B leakage in the cytoplasm, and increased IL-1β release. Another study had shown that removal of Aβ peptides and their aggregates helps reduce NLRP3 inflammasome [81]. Systemic inflammation reduced the clearance rate of Aβ by microglia in APP/PS1 mice. NLRP3 inflammasome knockout mice blocked microglial changes caused by LPS, including changes in microglial morphology and amyloid pathology [82]. Microglia, activated by signaling, can differentiate into either a pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype or an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype [83]. Lack of NLRP3 inflammasome biases microglia toward the M2 phenotype and leads to reduced Aβ deposition in the APP/PS1 model of AD, and the results suggest that inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome represents a novel therapeutic intervention for AD [79].

In addition to the above, Aβ can also promote the formation of NLRP3 inflammasome component ASC spots. Aβ induces the activation of NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles and promotes the production of ASC spots, which will accelerate the pathogenesis of AD. Venegas et al. [84] found that Aβ1–42 in APPSwePSEN1dE9 mice quickly binded to ASC spots after release and accelerated their oligomerization, thereby activating the inflammasome. One study found that soluble low-molecular-weight Aβ oligomers and fibrils induced the formation of ASC spots, and ASC was an important step in the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome, indicating that Aβ oligomers and fibrils could activate NLRP3 in microglia cells [85]. A great number of studies have demonstrated that in the brain of AD patients and AD animal models, high expression of IL-1β was detected in astrocytes and microglia. IL-1β is the main effector of NLRP3 inflammasome after activation. Many studies had found that in addition to senile plaques formed by insoluble fibrillar Aβ (fAβ) in AD patients, soluble oligomeric Aβ (oAβ) was also found in the cerebrospinal fluid and cortex of AD patients, which directly affected the cognitive decline of patients [86, 87]. Research by Parajuli et al. [88] indicated that oAβ could lead to the increase of pro-IL1-β to mature IL1-β in microglia through ROS-dependent NLRP3 activation. After Aβ treatment of astrocytes, the activation of inflammasome mediated by cathepsin B due to phagocytosis leads to IL1-β-dependent ASC production. Compared with ASC+/+ and ASC–/– cells, ASC+/– astrocytes reveal higher phagocytic activity, which was attributed to the higher release of chemokine C-C motif ligand 3 (CCL3). In the brains of 8-month-old 5×FAD mice carrying ASC+/– genotypes, the amyloid load was significantly reduced, which was related to the increased expression of CCL3 gene. In addition, the ASC+/– genotype rescued the spatial reference memory defects observed in 5×FAD mice. This genetic study revealed that ASC haploid deficiency could rescue the spatial reference memory deficit and amyloid plaque burden in 5×FAD mice [89].

In addition to the Aβ hypothesis has long been important in the pathogenesis of AD, many researchers believe that tau disease can’t be ignored in the etiology of AD. The progression of tau pathology was closely related to the progression of AD disease and was usually regarded as secondary tauopathy [90–92]. Tau protein activated NLRP3 inflammasome in primary microglia, and found that the lack of ASC in tau transgenic mice had a significant inhibitory effect on exogenous tau pathology and non-exogenous tau pathology, and the brain was given the NLRP3 inhibitor MCC950 suppressed exogenous tau pathology [93]. Ising et al. [94] analyzed the cortical samples of primary tau protein disease in 11-month-old and 3-month-old tau22 mice, and found that compared with young mice, the cleavage of CASP1 increased, and the level of ASC and mature IL-1β increased in aging mice, revealing that NLRP3 inflammasome was activated. Low levels of CASP1 cleavage and IL-1β, and reduced formation of ASC spots were detected in tau22 mice with NLRP3 inflammasome deficiency, and the lack of NLRP3 inflammasome components saved the spatial memory deficit in tau22 mice [94]. These indicate that the NLRP3 inflammasome is the core mechanism of AD inflammation.

NLRP3 inflammasome as a therapeutic target for AD

Although there are no clinical studies on NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitors for the treatment of AD, some studies suggest that NLRP3 inflammasome is regarded as a new target for AD treatment [95]. Several studies had shown that some exogenous compounds restrained inflammatory activity via distinct mechanisms, as shown in Table 1.

The underlying mechanism of several NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitors

| Sr no. | NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor | Models | Molecular mechanisms of NLRP3 activation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | JC-124 | TgCRND8 mice | Inhibited activation of NLRP3 inflammasome and reduced Aβ sedimentation and soluble and insoluble Aβ1–42 level | [96] |

| 2 | NSAIDs | 3×TgAD transgenic mice | Inhibited the release of IL-1β, inhibited cognitive impairment | [51] |

| 3 | MCC950 | APP/PS1 mice | Inhibited the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome and microglia, inhibited CASP1 activation and IL-1β release, reduced the accumulation of Aβ | [97] |

| 4 | Dl-NBP | APP/PS1 mice | Inhibited the expression of Nrf2, and the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome | [98] |

| 5 | Artemisinin | APPswe/PS-1dE9 transgenic mice | Reduced the activation of NF-κB and NLRP3 inflammatory corpuscles, and the Aβ deposition | [99] |

| 6 | DHM | APP/PS1 mice | Down-regulated the expression of NLRP3 inflammasome components NLRP3, ASC and CASP1 and reduced the release of IL-1β | [81] |

| 7 | EVOO | TgSwDI mice | Inhibited NACHT, LRR and PYD NLRP3 inflammasome | [100] |

| 8 | CS | APP/PS1 mice | Reduced Aβ deposition and microglia, inhibited NLRP3 inflammasome activation and restored synaptic membrane formation, and improved cognitive deficits | [101] |

| 9 | Edaravone | Aβ1−42 activated BV-2 microglia | Attenuated the depolarization of Δψm, reduced the production of ROS, and increased the activity of SOD-2, inhibited IL-1β secretion | [102] |

| 10 | BITC | LPS-induced BV2 microglia | Inhibited the activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes, and reduced pro-inflammatory mediator levels, including mtROS and ATP secretion | [103] |

| 11 | Pterostilbene | Aβ1–42-induced BV-2 cells | Reduced the expression and secretion levels of IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α | [104] |

| 12 | Stavudine | THP-1-derived macrophages were stimulated with Aβ42 or with Aβ42 after LPS-priming | Reduced the assembly of NLRP3 and the production of IL-18 and CASP1 | [105] |

| 13 | VX-765 | J20 mice | Prevented progressive Aβ peptide deposition, reversed brain inflammation, and normalized hippocampal synaptophysin levels | [106] |

| 14 | GRg3 | Intracerebral LPS injection in SD rats | Reduced LPS-induced cognitive impairment by inhibiting the expression of proinflammatory mediators in the hippocampus | [107] |

NSAIDs: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; Dl-NBP: Dl-3-n-butylphthalide; DHM: dihydromyricetin; EVOO: extra virgin olive oil; CS: choline supplementation; BITC: benzyl isothiocyanate; GRg3: Ginsenoside Rg3; SOD-2: superoxide dismutase-2; TNF-α: tumour necrosis factor alpha

The anti-diabetic drug JC124 approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has been shown to restrain the formation of NLRP3 inflammasome. After adult male SD rats were moderately damaged by cortical impact, JC124 treatment could significantly lessen the quantity of degenerative neurons induced by injury, the inflammatory cell reaction in the wounded brain and the volume of cortical lesions. The protein expression levels of NLRP3, ASC, CASP1, IL-1β, TNF-α and iNOS treated with JC124 were also significantly down-regulated in injured rats [108]. MCC950 had been considered as an effective NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor, and had potential clinical application value [109]. In 2015, Coll et al. [110] reported for the first time that a new type of specific NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor, MCC950, could inhibit NLRP3-induced ASC oligomerization, while having no significant inhibitory effect on AIM2, NLRC4 and NLRP1. In addition, there are other compounds such as Dl-NBP, artemisinin and DHM, et al. that affect the activation and generation of NLRP3 in the in vivo AD model. Phosphatidylcholine (PC) could inhibit Aβ-induced neurotoxicity and improved the cognitive impairment of AD rats induced by Aβ1–42 by reducing the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome and enhancing autophagy [111]. Otherwise, Lee et al. [112] found that intraperitoneal injection of GRg3 for 21 consecutive days could inhibit the inflammatory response caused by intracerebral LPS injection in SD rats, and significantly reduced LPS-induced cognitive impairment by inhibiting the expression of proinflammatory factors in the hippocampus.

Studies have shown that these drugs are very effective in the treatment of certain inflammation-related diseases and further studies are needed to investigate the effects of the above compounds on NLRP3 in patients with AD. Therefore, the development of more effective NLRP3 inhibitors for the prevention and treatment of AD is our focus.

Some of the above inhibitors can cause side effects in humans, while some have a high safety profile. Although NSAIDs can play a positive role in the treatment of AD, they cause damage to organs such as the stomach, small intestine, heart, liver, kidney, respiratory tract and brain due to their non-specific cytotoxicity [113]. MCC950, a specific inhibitor of NLRP3, blocked activation of typical and atypical NLRP3 but not of AIM2, NLRC4 or NLRP1 inflammasomes [110]. Dl-NBP acts as an inhibitor of NLRP3, but large samples, multicenter and high-quality randomized controlled trials are still needed to validate the clinical efficacy and safety of Dl-NBP due to the low quality of study methods [114]. Edaravone, in addition to being anti-neuroinflammatory, can bring about the side effect of glucose levels in the blood exceeding the absorption capacity of the kidneys [115].

Conclusions

In recent years, research on NLRP3 inflammasome has received considerable attention, and it has been confirmed that it plays a significant role in the development of AD. In the AD mouse model, NLRP3 inhibition can prevent memory loss and reduce Aβ deposition to a large extent, which demonstrates that targeting NLRP3 inflammasome is more likely in future AD treatment. NLRP3 inflammasome is a magnetic pharmacological target for the treatment of AD. Inhibition can specifically reduce pathological inflammation, and there are multiple points during activation pathway that can be suppressed without changing the basic microglial normal function. However, there are still a lot of important questions that need to be answered. First, the activation/inhibition mechanism of NLRP3 inflammasome and its mechanism for regulating the functional status of microglia and the pathophysiological process of AD are still unclear and need further research; second, currently there is no drug that can directly bind to and inhibit NLRP3 inflammasome to prevent or treat AD; finally, the specific NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitors are still effective and safe in AD patients to be verified by clinical trials. Therefore, we should try our best to perfect the study of neural inflammation mechanism network and translate it into AD treatment strategy.

Abbreviations

| AD: | Alzheimer’s disease |

| AIM2: | absent in melanoma 2 |

| ASC: | apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase-1 recruitment domain |

| Aβ: | amyloid β-protein |

| cAMP: | cyclic adenosine monophosphate |

| CARD: | caspase recruitment domain |

| CASP1: | caspase-1 |

| CLIC: | chloride intracellular channel |

| DAMPs: | damage-associated molecular patterns |

| Dl-NBP: | Dl-3-n-butylphthalide |

| IKK: | IκB kinase |

| IL-1β: | interleukin-1beta |

| LPS: | lipopolysaccharide |

| LRR: | leucine-rich repeat |

| mtDNA: | mitochondrial DNA |

| mtROS: | mitochondrial reactive oxygen species |

| NEK7: | never in mitosis A-related kinase 7 |

| NF-κB: | nuclear factor κB |

| NLRC4: | nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor C4 |

| NLRP3: | nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 |

| NLRs: | nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptors |

| NOD: | nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain |

| PAMPs: | pathogen-associated molecular patterns |

| PRRs: | pattern recognition receptors |

| PYD: | pyridine domain |

| ROS: | reactive oxygen species |

| SD: | Sprague-Dawley |

| TLRs: | toll-like receptors |

| TRX: | thioredoxin |

| TXNIP: | thioredoxin-interacting protein |

| VRAC: | volume-regulated anion channel |

Declarations

Author contributions

XG wrote the original draft of the manuscript; XZ, YS and XD wrote the review; XZ edited the review; XG, YS and XD revised the manuscript; XD conceptualized the manuscript and made the funding acquisition. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read and approved the submitted version.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (6164030), 2019 Basic Research Projects of Beijing Union University, Beijing Key Laboratory of Bioactive Substances and Functional Foods Research Project, the Academic Research Projects of Beijing Union University (No. ZK80202102, XP202007), and Graduate Funding Project in Beijing Union University. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2022.