Abstract

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a substantial and growing problem worldwide and has become the second most common indication for liver transplantation as it may progress to cirrhosis and develop complications from portal hypertension primarily caused by advanced fibrosis and erratic tissue remodeling. However, elevated portal venous pressure has also been detected in experimental models of fatty liver and in human NAFLD when fibrosis is far less advanced and cirrhosis is absent. Early increases in intrahepatic vascular resistance may contribute to the progression of liver disease. Specific pathophenotypes linked to the development of portal hypertension in NAFLD include hepatocellular lipid accumulation and ballooning injury, capillarization of liver sinusoidal endothelial cells, enhanced contractility of hepatic stellate cells, activation of Kupffer cells and pro-inflammatory pathways, adhesion and entrapment of recruited leukocytes, microthrombosis, angiogenesis and perisinusoidal fibrosis. These pathological events are amplified in NAFLD by concomitant visceral obesity, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes and dysbiosis, promoting aberrant interactions with adipose tissue, skeletal muscle and gut microbiota. Measurement of the hepatic venous pressure gradient by retrograde insertion of a balloon-tipped central vein catheter is the current reference method for predicting outcomes of cirrhosis associated with clinically significant portal hypertension and guiding interventions. This invasive technique is rarely considered in the absence of cirrhosis where currently available clinical, imaging and laboratory correlates of portal hypertension may not reflect early changes in liver hemodynamics. Availability of less invasive but sufficiently sensitive methods for the assessment of portal venous pressure in NAFLD remains therefore an unmet need. Recent efforts to develop new biomarkers and endoscopy-based approaches such as endoscopic ultrasound-guided measurement of portal pressure gradient may help achieve this goal. In addition, cellular and molecular targets are being identified to guide emerging therapies in the prevention and management of portal hypertension.

Keywords

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, sinusoidal homeostasis, portal hypertension, portal venous pressure, hepatic venous pressure gradient, portal pressure gradient, endoscopic ultrasound, metabolic biomarkersIntroduction

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) affects more than a billion people worldwide with substantial geographic variation in its prevalence including 25–30% in the US population and up to 60% reported in the Middle East, representing therefore an enormous and growing healthcare burden [1–3]. NAFLD has been considered a hepatic manifestation of the increasingly prevalent metabolic syndrome and is associated with visceral obesity, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia and endothelial dysfunction [4]. Of note, there is an emerging consensus for new terminology to define NAFLD as metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) [5, 6]. The histological spectrum of NAFLD includes steatosis, which is relatively benign, and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) with a variable degree of liver fibrosis, which may progress into cirrhosis with a high risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma and other grave complications including esophageal variceal bleeding, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy and liver failure [7]. Risk factors that predispose individuals to variable clinical outcomes have not been fully elucidated, although fibrosis has been identified as a key histological predictor of liver-related and all-cause mortality in NAFLD [8].

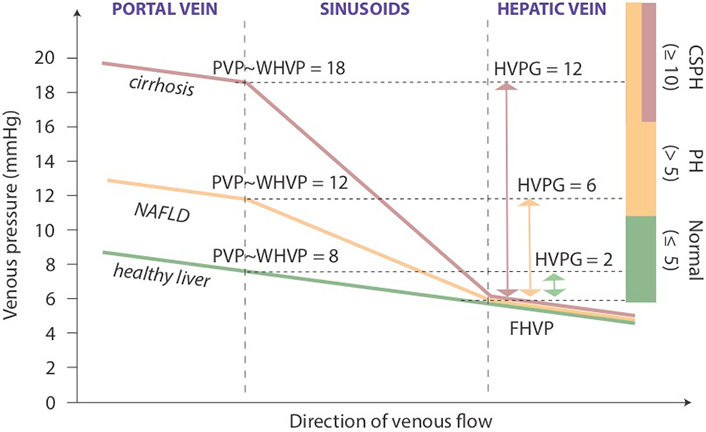

One of the major consequences of extensive fibrosis with parenchymal and vascular remodeling in cirrhosis is the development of portal hypertension [9, 10]. Portal hypertension is present when portal venous pressure (PVP) is supraphysiological, but direct measurement of blood pressure in the portal vein has been technically challenging other than in experimental or intraoperative settings. As discussed later in more detail, portal hypertension in the clinical practice has been therefore defined by the hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG), which is measured in the hepatic vein from the difference between pressure readings of a wedged and free-floating venous catheter. Accordingly, portal hypertension is defined by an HVPG above 5 mmHg and clinically significant portal hypertension (CSPH) is defined by an HVPG at or above 10 mmHg, predicting the development of esophageal varices and other complications [11, 12]. Portal hypertension is classified as pre-sinusoidal, sinusoidal or post-sinusoidal according to the major site of impediment in hepatic vascular flow [13]. Sinusoidal portal hypertension is the most common form that may complicate cirrhosis of any etiology [9]. In cirrhosis, sinusoidal architecture becomes grossly distorted leading to increased intrahepatic vascular resistance (IHVR) aggravated by additional and profound vasoregulatory changes in splanchnic and systemic circulation. However, increasing clinical and experimental evidence indicates that sinusoidal portal hypertension may develop in early stages of NAFLD when fibrosis is far less advanced or absent [14–16]. There is also evidence that NAFLD-inducing interventions such as the Western diet worsens an already existing portal hypertension [17]. While HVPG in may remain below the threshold of CSPH with no immediate effect on clinical outcomes in NAFLD, it reflects an anomaly in the complex physiology of liver hemodynamics and may contribute to the progression of NAFLD [18, 19]. It is therefore important to understand the cellular and molecular regulation of sinusoidal homeostasis and develop safe, reliable and noninvasive methods to detect and monitor portal pressure. This will provide an opportunity for the discovery of therapeutic targets to prevent and manage early portal hypertension in NAFLD.

Early increase of portal venous pressure in NAFLD

Increased PVP and other hemodynamical parameters suggesting portal hypertension have been observed in multiple experimental models of NAFLD. One of the earliest reports described the impact of choline-deficient diet on PVP in rats developing fatty liver, fatty liver with fibrosis, or fatty cirrhosis [20]. Interestingly, decreased portal blood flow, sinusoidal narrowing and higher PVP were readily detectable in animals only having fatty liver, suggesting that steatosis in this experimental paradigm was sufficient to induce portal hypertension [20]. Subsequent studies described additional changes in sinusoidal homeostasis linked to the development of portal hypertension in various experimental models of fatty liver (Table 1).

Changes in hepatic vascular parameters reported in experimental NAFLD

| Authors/Year | Study type | Liver disease characteristics | Major findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wada et al. (1974) [20] | Male Donryu rats, choline-deficient vs. control diet(n = 12 vs. 27) | Steatosis, steatosis with fibrosis, or cirrhosis after 8 to 38 weeks of intervention | Sinusoidal narrowing, decreased venous flow (60%), and increased portal pressure present in steatosis alone |

| Seifalian et al. (1999) [21] | New Zealand white rabbits, high cholesterol vs. control diet for 4, 8, and 12 weeks(n = 6 vs. 18) | Steatosis | Total hepatic blood flow (137 ± 6 mL/min) reduced to 99 ± 5 mL/min (P < 0.002), and 63 ± 5 mL/min (P < 0.002) in steatotic livers after 8 and 12 weeks, respectively |

| Sun et al. (2003) [22] | Male Zucker obese vs. lean rats (25 to 30 weeks of age)(n = 7 vs.7) | Massive steatosis, no cirrhosis | Reduced total hepatic blood flow (35%) and portal venous flow (38%) in steatosis |

| Francque et al. (2010) [23] | Male Wistar rats, methionine-choline-deficient vs. control diet for 4 weeks(n = 12 vs. 12) | Steatosis with nearly absent inflammation and no fibrosis | Vasodilator response to phenylephrine blunted in steatotic livers and portal venous pressure increased from 2.8 ± 0.5 mmHg to 9.0 ± 0.7 mmHg (P < 0.001) |

| Pasarin et al. (2012) [24] | Male Wistar Kyoto rats, cafeteria vs. control diet for 1 months(n = 7 vs. 7) | Steatosis without inflammation or fibrosis | Vasodilator response to acetylcholine blunted in steatotic livers and IHVR increased 2.2-fold |

| Garcia-Lezana et al. (2018) [25] | Male Sprague-Dawley rats, high-glucose/fructose, high-fat vs. control diet (n = 6 vs. 6) for 8 weeks (experiment 1) used for heterologous vs. autologous fecal microbiota transplantation (experiment 2)(n = 10 to 14) | Steatohepatitis with mild or absent fibrosis | Dietary intervention increased PVP from 8.75 ± 0.52 mmHg to 10.71 ± 0.44 mmHg (P = 0.018), but corrected by fecal microbiota transplantation derived from rats on control diet |

| Van der Graaff et al. (2018) [26] | Male Wistar rats, methionine-choline-deficient vs. control diet for 4 weeks (experiment 1, n = 12 vs. 12) validated in experiment 2(n = 12 vs. 12) | Severe steatosis with mild lobular inflammation and absent fibrosis | Vasoconstriction less responsive to blunting by indomethacin in steatotic livers and transhepatic pressure gradient increased to 9.5 ± 0.5 mmHg from 2.3 ± 0.5 mmHg in controls (P < 0.001) |

Changes in liver hemodynamics consistent with increased IHVR and at least some degree of portal hypertension have also been detected in several clinical studies involving patients with variably advanced NAFLD (Table 2). Some of these works were based on Doppler ultrasonography and utilized various flow parameters of major hepatic vessels (e.g., portal vein pulsatility index and hepatic arterial resistance index) to describe anomalies in portal venous flow associated with NAFLD [27, 28]. An important observational study analyzed the prevalence of portal hypertension in a cohort of 354 patients who underwent liver biopsy for staging of NAFLD [15]. While 100 patients had evidence of portal hypertension (based on clinical symptoms and without HVPG measurement), fibrosis was mild or absent in a subgroup of 12 patients and the findings indicated that even CSPH may develop in the absence of cirrhosis if steatosis is sufficiently severe [15]. Further studies provided more definitive evidence that portal hypertension can manifest in noncirrhotic NAFLD. In a prospective study, HVPG exceeded 5 mmHg in 8 out of 40 (20%) patients diagnosed with NAFLD but without cirrhosis based on transjugular liver biopsy [29]. In another cohort of 50 patients with NAFLD, in which 14 subjects had an HVPG > 5 mmHg (8.8 ± 0.7 mmHg) and 36 subjects an HVPG ≤ 5 mmHg (3.4 ± 0.2 mmHg), steatosis was the only histological feature that significantly differed between the two groups (both groups was dominated by no fibrosis (F0) and only one case of cirrhosis was verified in each) [30]. Although liver biopsy is inherently prone to sampling error and may underreport fibrosis due to disease heterogeneity in the liver, these observations suggest that portal hypertension may develop when histological features of NAFLD are limited to steatosis or include less than advanced fibrosis.

Changes in hepatic vascular parameters reported in human NAFLD

| Authors/Year/Country | Study type | Liver disease characteristics | Major findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Balci et al. (2008) Turkey [27] | Prospective study of 140 patients with variable degree of ultrasound-proven steatosis | Steatosis No liver biopsy available | Venous pulsatility index and mean flow velocity inversely associated with degree of steatosis (P < 0.01) |

| Mendes et al. (2012) USA [15] | Retrospective study of 100 patients with PH identified from a cohort of 354 cases with biopsy-proven NAFLD | NAFLD with variable degree of fibrosis (F0, F1–2, F3, and F4: n = 27, 30, 13 and 30, respectively | 23 patients with PH (varices, encephalopathy, ascites or splenomegaly) had no cirrhosis, including 12 patients with F2 or lesser fibrosis. Steatosis was more severe in those with PH |

| Hirooka et al. (2015) Japan [28] | Prospective study of 121 patients with histologically proven NAFLD | NAFLD with variable degree of fibrosis (F0 through F4,n= 41, 22, 19, 23, and 16, respectively) | Arterioportal flow ratio correlated with increasing stages of liver fibrosis in pair-wise comparisons (P < 0.001) including higher readings in some patients with F0 and F1 |

| Francque et al. (2011) Belgium [30] | Prospective study of 50 patients with obesity and biopsy-proven NAFLD and HVPG measurement | Steatosis or steatohepatitis with variable degree of liver fibrosis including cirrhosis | PH (HVPG > 5 mmHg) was verified in 28% and correlated with the extent of steatosis (P = 0.016) but not with inflammation, ballooning or fibrosis |

| Vonghia et al. (2015) Belgium [29] | Prospective study of 40 patients with obesity undergoing transjugular liver biopsy and HVPG measurement | Steatosis (n = 12) and steatohepatitis (n = 28) without cirrhosis | PH (HVPG > 5 mmHg) was verified in 8 patients of this noncirrhotic cohort and found to be clinically significant in one case |

| Rodrigues et al. (2019) Switzerland [16] | Retrospective study of 157 patients with liver disease undergoing histological and liver hemodynamic evaluation | Liver disease of mixed etiology including 45 cases of NAFLD with variable degree of fibrosis or cirrhosis | HVPG ≥ 10 mmHg was found in 89 patients, including 14 cases (16%) without cirrhosis but presence of ballooning and lobular inflammation (NAFLD, n = 5) |

| Semmler et al. (2019) Austria [31] | Retrospective study of 261 patients undergoing HVPG measurement and liver fat was determined by histology as well as by controlled attenuation parameter | 205 patients (78.5%) had cirrhosis of which 88 (33.7%) cases were associated with (non) alcoholic fatty liver disease | HVPG ≥ 10 mmHg was found in 191 patients (73.2%). Negative correlation was found between steatosis and HVPG at F2 fibrosis and higher, while no correlation was found with F0/F1 fibrosis. No subgroup analysis of NAFLD-only patients |

PH: portal hypertension; F1: minimal fibrosis; F2: moderate fibrosis; F3: advanced fibrosis; F4: severe fibrosis

A retrospective analysis from the University of Bern, Switzerland, included 89 patients with suspected cirrhosis of various etiology based on clinical, laboratory and radiological features consistent with CSPH undergoing HVPG measurement and liver biopsy [16]. While 75 patients with HVPG ≥ 10 mmHg had histological confirmation of cirrhosis, 14 patients (16%) had no cirrhosis and this group included 5 patients with NAFLD [16]. Based on METAVIR scores, 7 patients had stage F3 fibrosis, 4 patients had stage F2 fibrosis, and 3 patients had stage F0 or F1 fibrosis. Notably, all 14 cases in this subgroup had perisinusoidal fibrosis and many featured hepatocellular ballooning (n = 8), histological changes that have been associated with increased sinusoidal pressure [16].

Most recently, a group from the Medical University of Vienna, Austria, published a retrospective observational study that questioned the link between steatosis and portal hypertension [31]. The authors drew their conclusions from a cohort of 261 patients undergoing simultaneous HVPG measurements and transient liver elastography complemented with liver fat content estimation by controlled attenuation parameter (CAP). Etiologies of liver disease included viral hepatitis B and C (47.5%), (non)-alcoholic fatty liver disease (33.7%), and cholestatic liver disease (4.6%) with cryptogenic and other causes of chronic liver disease in the rest (14.2%). Surprisingly, CAP correlated negatively with HVPG in patients with liver stiffness less than 12.8 kPa (ρ = –0.512, P < 0.001) as well as in patients with liver stiffness of 12.8–25.7 kPa (ρ = –0.293, P = 0.048). Moreover, there was no association between CAP and HVPG in the (non) alcoholic fatty liver disease group [31]. There are several caveats, however. First, only a small fraction of the cohort had NAFLD, which could not be analyzed separately from alcohol-associated liver disease. Second, the cohort mostly consisted of patients with advanced liver disease where a median liver stiffness was 28.0 kPa (IQR: 14.2–55.1) and a mean HVPG was 15.2 ± 7.5 mmHg, confirming CSPH in 191 patients (73.2%) at presentation. Third, liver fat content was overall low (159 patients i.e. 60.9% of the entire cohort had no steatosis), a phenomenon frequently seen in patients with advanced liver disease. Accordingly, portal hypertension in a cohort of patients mostly featuring compensated and decompensated cirrhosis is more likely to reflect the impact of advanced fibrosis and tissue remodeling in the liver.

Pathogenesis of sinusoidal dysfunction in NAFLD

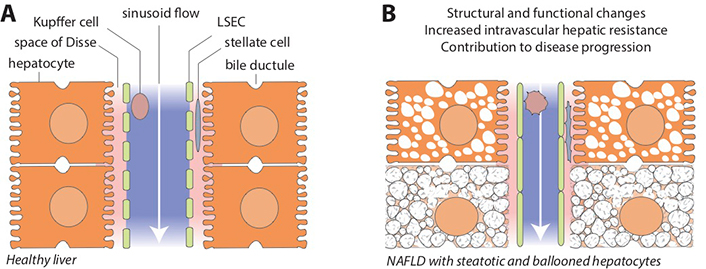

Sinusoids are complex structural and functional units of the liver, encompassing all major cellular, humoral and vascular components of hepatic physiology and biochemistry (Figure 1A). The unique capillary network of sinusoids is formed by the confluence of terminal hepatic arterioles and branches of the portal vein, mixing highly oxygenated arterial blood from the systemic circulation with partially deoxygenated, nutrient-rich venous blood from the splanchnic area [32]. Sinusoid vascular regulation is also unique in a sense that it efficiently throttles high hydrostatic pressure of the arterial inflow to the level of low-flow, low-pressure portal circulation [33, 34]. This is critically important to prevent shear stress and other adverse effects of high pressure in liver sinusoids under physiological conditions.

Hepatic sinusoids in healthy liver and in NAFLD. A. Schematic view of the liver sinusoidal space and its major cellular components. Blood flow from the portal area toward the central vein (white arrow) is unimpeded in normal conditions. Microvilli of hepatocytes face the perisinusoidal space (space of Disse, pink area), separated from the sinusoidal lumen (blue area) by the fenestrated plasma membrane of LSECs. Hepatic stellate cells reside in the space of Disse and Kupffer cells in the sinusoids; B. NAFLD is associated with structural and functional changes that may profoundly affect sinusoid homeostasis by promoting endothelial dysfunction, distorting sinusoidal microanatomy and disrupting cross-talk among various liver cells, ultimately leading to increased intravascular hepatic resistance and contributing to disease progression (see main text and Figure 2 for cellular and molecular pathways involved in this process). LSEC: liver sinusoidal endothelial cell

Mechanical changes that affect sinusoids early in NAFLD include enlarged hepatocytes due to lipid accumulation and ballooning injury caused by lipotoxicity and other pathological events (Figure 1B). Lipid-laden hepatocytes may reduce sinusoidal space by 50% compared with normal liver architecture [35]. While this process in NAFLD typically begins close to the central vein (zone 3) where de novo lipogenesis and lipid droplet formation is most active, the process may expand across the entire length of the sinusoids [36, 37]. Ballooned hepatocytes may increase their size 1.5 to 2 times, further encroaching on the sinusoid space [38]. Although these initial structural changes are certainly less dramatic than the distorted sinusoidal architecture seen with extensive fibrosis and tissue remodeling in cirrhosis, early sinusoidal compression and microcirculatory anomalies may begin to disrupt cellular and molecular pathways of sinusoidal homeostasis and promote the development of portal hypertension.

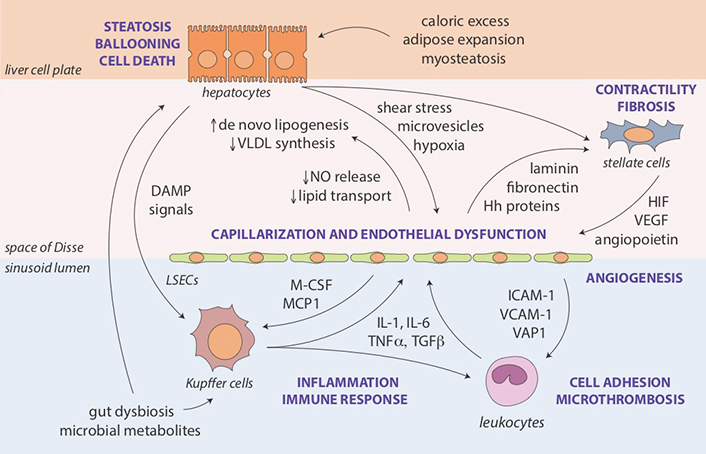

Perturbed interactions and regulatory feedback loops between hepatocytes, LSECs, hepatic stellate cells, resident liver macrophages or Kupffer cells and other innate immune system components recruited to the liver represent another layer in the pathogenesis of sinusoidal dysfunction and increased IHVR in NAFLD (Figure 2). The complexity of liver cell-cell interactions makes it difficult to establish the chronology of cell-specific changes in structural and functional phenotypes [19]. Damage-associated molecular patterns and pro-inflammatory microvesicles (exosomes) released from steatotic and ballooned hepatocytes activate Kupffer cells [39] and the liver inflammasome [40]. LSECs respond to shear stress and hypoxia by losing their fenestrated endothelium (capillarization), which is a cardinal feature of endothelial dysfunction [41]. Capillarized LSECs impair hepatic lipid transport and metabolism [42], secrete bioactive substances that promote microthrombosis and angiogenesis [43], and their diminished nitric oxide (NO) production allows hepatic stellate cells to change their phenotype [44]. First, upregulation of smooth muscle proteins actin and myosin in stellate cells increases their contractility, which may impede sinusoidal flow similar to pericytes in the systemic circulation [45]. Second, activated stellate cells become the source of extracellular matrix deposits, resulting in gradually more severe fibrosis and encroachment on the sinusoidal lumen [46, 47]. Perisinusoidal fibrosis (collagen deposition in the space of Disse), an early feature seen in many NAFLD cases, has been correlated with increased portal pressure [48].

Molecular and cellular pathways of sinusoidal dysfunction in NAFLD. Key mechanisms and intermediate disease pathophenotypes implicated in the development of portal hypertension in NAFLD. Steatosis as an initial feature of the metabolic syndrome in the liver results from interactions with extrahepatic sites affected by caloric excess and insulin resistance (adipose tissue expansion [49], myosteatosis [50] and gut dysbiosis [51, 52]), as well as from endogenous lipid synthesis enhanced by structural (e.g., capillarization) and functional (e.g., impaired NO release) changes in LSECs [42]. Lipotoxicity may lead to ballooning injury of hepatocytes, contributing further to shear stress, cellular hypoxia, endothelial dysfunction, and activation of Kupffer cells and stellate cells [53, 54]. Augmented inflammatory and immune responses include the recruitment additional cellular components of innate immunity (e.g., polymorphonuclear leukocytes) promoting adhesion and microthrombosis [55]. Loss of NO-mediated tonic control by hepatocytes and LSECs combined with an abundance of activating mediators stimulates contractility and transformation of stellate cells into myofibroblasts leading to fibrosis and angiogenesis, further narrowing the sinusoidal space and increasing intrahepatic vascular resistance [41, 46]. Hh: Hedgehog; HIF: hypoxia-inducible factor; ICAM: intercellular adhesion molecule; IL: interleukin; M-CSF: macrophage colony-stimulating factor; MCP: monocyte chemoattractant protein; TGF: transforming growth factor-beta; TNF: tumor necrosis factor-alpha; VAP: vascular adhesion protein; VCAM: vascular cell adhesion molecule; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; VLDL: very low-density lipoprotein

Methods for the detection of portal pressure in NAFLD

To assess the degree of portal hypertension, PVP is traditionally measured by retrograde occlusion of a hepatic vein tributary with a balloon-tipped central vein catheter, which detects wedged and free hepatic venous pressure (WHVP and FHVP, respectively) [56]. In sinusoidal portal hypertension associated with cirrhosis, the largest pressure difference compared to physiological conditions is seen between the beginning and the end of sinusoids (Figure 3). Using umbilical vein pressure as reference, wedged hepatic venous pressure (WHVP) in cirrhotic patients is almost identical to PVP, and the pressure difference between wedged and free-floating catheter positions defines the HVPG, which became a widely accepted measure of portal hypertension [57, 58].

Portal and hepatic venous pressure in sinusoidal portal hypertension. Schematic diagram with representative examples of PVP changes across the liver in health, NAFLD and cirrhosis. Colored bars on the right indicate ranges of PVP defined for clinical management. FHVP: free hepatic venous pressure; PH: portal hypertension

While HVPG is considered the benchmark for assessing portal hypertension, it is highly operator-dependent and therefore specific training is required [57, 59]. Its excellent reproducibility and reliability of HVPG is largely based on a handful of centers with large experience in the proper measurement of HVPG [60]. Another disadvantage is that HVPG is not able to accurately detect pre-sinusoidal causes of portal hypertension (e.g., portal vein thrombus) [57].

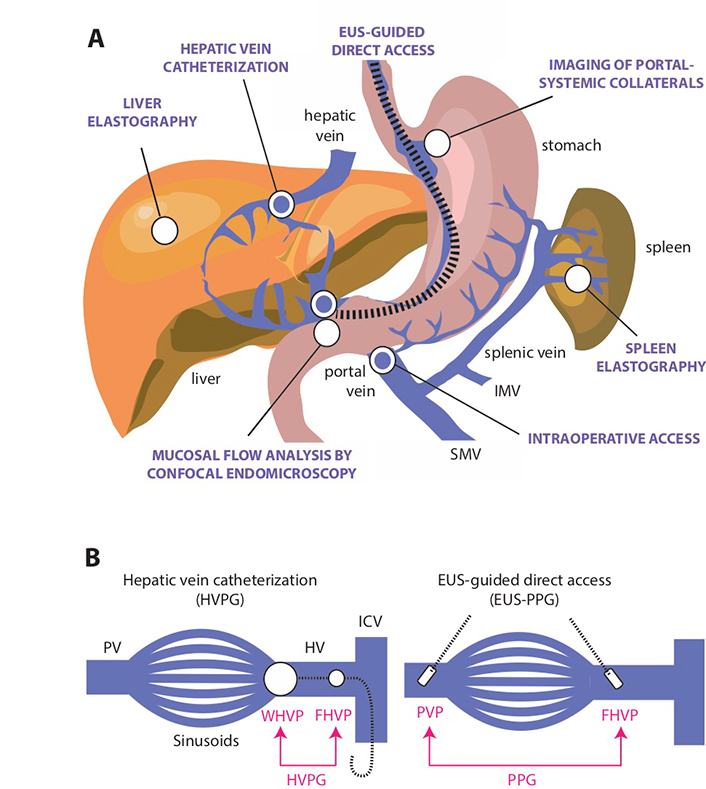

In addition to HVPG, there are other techniques to indirectly estimate portal pressure but none have entered clinical practice as a reliable substitute (Figure 4). Ultrasonographic detection of hemodynamic alterations consistent with increased IHVR may help in the diagnosis of portal hypertension associated with NAFLD [19]. Portal hypertension in experimental fatty liver is characterized by deceleration of portal vein flow and a corresponding increased flow in the hepatic artery [21]. The hepatic artery resistivity index or HARI [defined as (peak systolic flow - end diastolic flow) / peak systolic flow measured in the common hepatic artery] is another measure of microcirculatory resistance in the liver that has been applied to the staging of NAFLD [61, 62]. More recent ultrasonography-based techniques in the evaluation of portal hypertension include subharmonic aided pressure estimation (SHAPE) [63], a type of dynamic contrast material-enhanced (DCE) ultrasonography used in conjunction with encapsulated microbubbles, has been studied to correlate with hepatic vessel pressures [64]. Tissue stiffness of the liver and/or spleen as determined by vibration controlled transient elastography or shear wave elastography have been found to correlate with HVPG with good performances (AUROC 0.76–0.99) [65, 66]. However, the cut-off value for clinically significant portal hypertension is variable in these studies (between 13.6 kPa and 34.9 kPa) due to the heterogeneity of study populations [67–70]. Moreover, there is a high risk of misinterpretation due to the impact of feeding state on liver and spleen stiffness [71, 72].

Direct and indirect methods for the assessment of portal hypertension. A. Several minimally invasive or non-invasive approaches (indicated by white circles) have been developed to estimate portal venous pressure, including endoscopic visualization or imaging of portal-systemic collaterals by various methods based on abdominal sonography [28, 63, 64, 79], computer tomography [80] and multi-parametric MR imaging [81]; tissue stiffness assessment of the liver and spleen by vibration-controlled transient elastography or 2-dimensional (gradient-recalled echo) MR elastography [65, 82–84]; and analysis of mucosal vascular pattern and flow by confocal endomicroscopy [78]. Direct access methods (indicated by blue circles) include HVPG measurement, which is the reference technique for measuring portal hypertension, and the occasional opportunity to obtain intraoperative access to the portal vein [57, 85, 86]. EUS-guided portal and hepatic vein access is an emerging method to provide safe and direct measurement of portal pressure gradient (PPG) [87, 88]; B. Comparison of the classic hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) method using indirect access through the hepatic vein to estimate PVP and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided assessment of through direct access of the portal vein and hepatic vein. To calculate HVPG, a balloon-tipped central vein catheter is inserted into a hepatic vein tributary where retrograde occlusion detects WHVP and keeping the catheter “free” in the hepatic vein detects FHVP [57, 85]. In cirrhotic patients, WHVP is almost identical to PVP and the pressure difference between wedged and free-floating catheter positions defines HVPG [89]. To calculate PPG, the portal and hepatic vein is accessed through insertion of a digital pressure detection device by EUS-guided technique to calculate the difference between PVP and FHVP [87, 88]. SMV: superior mesenteric vein; IMV: inferior mesenteric vein; PV: portal vein; HV: hepatic vein

Magnetic resonance (MR)-based methods including MR elastography (MRE) in the detection of portal hypertension are also rapidly emerging [73, 74]. In a small cohort of patients with cirrhosis due to various etiologies including NASH, 2-dimensional (gradient-recalled echo) MRE showed excellent correlation with a wide range of HVPG (3–16 mmHg) [75], and may differentiate between noncirrhotic and cirrhotic portal hypertension [76]. In a recent proof-of-concept study, for non-invasive assessment of portal hypertension by multiparametric MR imaging, iron-corrected T1 relaxation time of the spleen has shown an excellent diagnostic accuracy for both portal hypertension (HVPG > 5 mmHg) and CSPH (HVPG ≥ 10 mmHg) with an AUROC of 0.92 for both conditions [77]. Finally, anatomical and microcirculatory changes detected by probe-based confocal laser endomicroscopy of the duodenal mucosa have also been associated with portal hypertension [78].

Direct assessment of portal pressures is feasible via surgical, percutaneous transhepatic, or transvenous (transjugular) catheterization of the portal vein, although these techniques are less frequently performed [90]. The EUS-guided PPG measurement potentially represents a new, potentially scalable modality for direct portal venous pressure measurements in clinical practice.

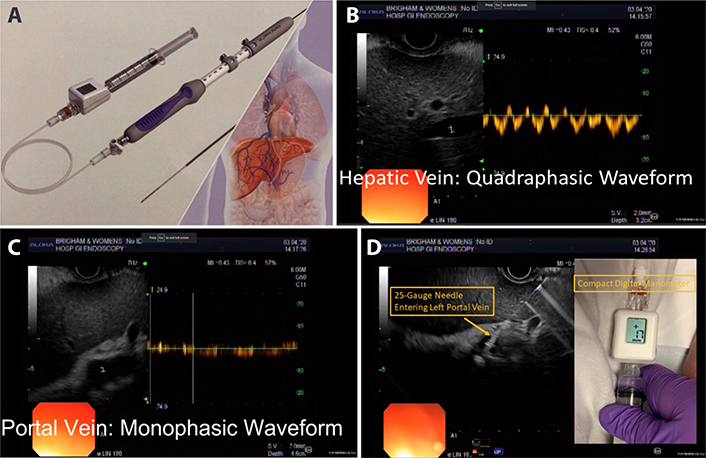

The device is a modified 25-gauge fine needle aspiration (FNA) needle connected to a digital compact manometer and has been recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for direct pressure readings of the portal vein and hepatic vein [91] (Figure 5). The echoendoscope is advanced into the stomach and the portal and hepatic veins are sonographically visualized. With the compact manometer residing in the right midaxillary line, the hepatic and portal veins are sequentially accessed in transgastric, transhepatic fashion. Three pressure readings are obtained from the hepatic vein and portal vein, respectively, and the mean difference is reported as the PPG. The following characteristics of the device and procedure theoretically mitigates against concerns of bleeding, even in patients with cirrhosis: small caliber of needle, EUS guidance, and slow withdrawal of the needle across liver parenchyma to tamponade the access site. A human pilot study in 28 patients demonstrated 100% technical success (EUS-PPG measurements of 1.5 mmHg to 19 mmHg) and no adverse events, including bleeding [92]. A prior porcine study comparing EUS-PPG vs. HVPG showed excellent correlation (Pearson’s correlation coefficient R = 0.985–0.99) [87]. Looking ahead, the ideal application for EUS-PPG may be for a patient with defined or suspected chronic liver disease and another indication for endoscopy (e.g., variceal screening/surveillance, EUS-guided liver biopsy, abdominal pain); clinical studies are underway to further delineate optimal patient selection.

EUS-guided measurement of the PPG (EUS-PPG) A Portal pressure gradient measurement device with modified FNA needle and compact manometer (Cook EchoTip Insight. Bloomington. IN; FDA approved) [91]; B. Doppler interrogation of middle hepatic vein with characteristic four-phase waveform; C. Doppler interrogation of left portal vein with characteristic monophasic waveform; D. Advancement of 25-gauge needle in transgastric. transhepatic fashion into the left portal vein. Digital read-out of compact manometer

Emerging biomarkers of portal hypertension

Due to the invasive nature of the methods of detection of portal pressure, in quest for less invasive diagnostics, several recent studies have focused on developing biomarkers to predict portal hypertension and its complications. There are a limited number of proposed markers that reflect the complex structural and functional changes of the gut-liver axis, which is the key underlying pathophysiological and anatomical substrate of portal hypertension [93–95]. The disturbance of the harmonic crosstalk between the intestinal barrier, beneficial microbiota and the liver and its immune system plays a central role in the development of sinusoidal dysfunction and increased intravascular resistance. “Leaky gut” (i.e. the increased intestinal permeability) induced by disruption of the intestinal barrier leads to bacterial translocation and the activation of Kupffer cells, which produce pro-inflammatory mediators. Accordingly, it has been proposed that Kupffer cell-specific markers, such as the soluble CD163 scavenger receptor and the enzyme heme-oxygenase-1 (HO-1) independently correlate with HVPG, while several other inflammatory markers and especially TNF-β, and heat shock protein 70 (HSP-70) have been used in predictive statistical models [96–99].

As shown in Figure 2, sinusoidal dysfunction is an early hallmark in the pathogenesis of portal hypertension. NO regulates the function of sinusoidal endothelial cells and several experimental and clinical studies reported correlation between NO levels and PVP [100], while circulating endothelial cells (CEC) and the CEC to platelet count ratio may non-invasively reveal augmented shear stress and vascular injury in liver sinusoids [101]. Consistent with the development of perisinusoidal fibrosis as an early feature in many NAFLD cases, markers of fibrosis such as laminin can predict HVPG > 5 mmHg with a diagnostic efficiency of 81% and other fibrosis markers such as degraded elastin, collagen IV and collagen V were all significantly increased in patients with HVPG ≥ 10 mmHg [100, 102].

Several excellent reviews summarize in detail these efforts to discover non-invasive biomarkers for the assessment of portal hypertension and cirrhosis [99, 100, 103]. Notably though, very few studies have used large-scale -omics technologies and integrative systems biology approaches in patients with portal hypertension and especially with those at early stages. This is due to the limited use of portal pressure measurement methods and the clinical reality that performing HVPG measurements in patients with less advanced liver disease is rarely considered due to its inherent risks. Such studies however will be very informative. Especially the metabolite profiling of blood samples derived from patients with different levels of portal hypertension and the correlation between those levels and the blood metabolites is an excellent research system for the discovery of relevant non-invasive biomarkers in NAFLD. Metabolomic signatures, which essentially incorporate both genetic and environmental inputs, may be convenient and practical readouts for studies on diagnostic, prognostic and predictive factors in NAFLD, in which the interaction between genetic and environmental factors appears to play a substantial role [104–106]. Unique microbiome-derived signatures may correlate with early pressure increases, since both NAFLD and liver cirrhosis are associated with microbiome changes [52, 93, 107]. Furthermore, since NAFLD is strongly associated with the metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance, the levels of specific markers of metabolic status may also be early indicators of portal hypertension, or their serial measurements may reveal trending patterns towards early increases in portal pressure.

State-of-the-art metabolite profiling platforms are essentially highly parallel assay systems that can rapidly screen for useful biomarkers-signatures of physiologic state, disease status, predictors of future disease or preventive and therapeutic targets [108, 109]. Metabolomics platforms probe hundreds of compounds of known identity and tenths of thousands of unidentified signals (untargeted metabolite profiling) [110]. Thus, many potential biomarkers can be measured simultaneously in the same sample maximizing the efficient use of valuable samples. This also allows both a wide-ranging survey of individual metabolites as potential intermediate phenotypes or predictors of disease progression, and also integrated analysis of multiple metabolites as composite measures. Importantly, recent technical developments such as the ability to perform EUS-guided measurement of PPG will allow to gain unprecedented and direct access to portal and hepatic circulation. This technique will enable simultaneous measurement of the pressures in portal and hepatic veins and collection of blood samples from these vessels, providing a unique opportunity to comprehensively catalogue portal and hepatic vein metabolite signatures in patients with NAFLD and other conditions. The effect of the liver on the levels of thousands of metabolites will be evaluated, as these will be measured directly at the liver input and output sites. This technique will not only allow insights about liver function in NAFLD that were not possible before but, more importantly, it will enable correlations between thousands of metabolites with different PVP levels. Thus, it will tremendously facilitate the development of novel biomarkers and methods that will be helpful in early stage diagnosis and may reduce significantly or even eliminate the need for invasive techniques.

Prevention and treatment of portal hypertension in NAFLD

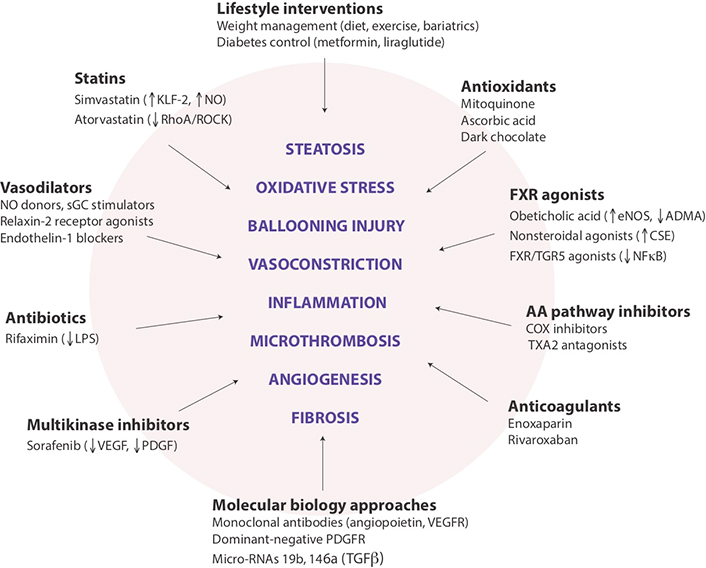

The complex physiology of liver sinusoids offers a variety of cellular and molecular targets for mitigating the impact of NAFLD on IHVR (Figure 6). Since prevention is usually the best therapeutic strategy, lifestyle interventions aimed at reducing excess caloric intake and controlling adversities of obesity and type 2 diabetes on the liver should be mentioned first. A large number of drug candidates are being considered for the management of portal hypertension, although many of these agents have not yet entered clinical investigation and evidence for their effectiveness is limited to experimental models. Moreover, it remains to be seen which drugs become safely applicable to noncirrhotic NAFLD by targeting early and reversible components of sinusoidal endothelial dysfunction. Only a few major pharmacological approaches are mentioned here specifically, as several recent reviews extensively described the mechanisms of action and effectiveness of these agents [19, 55, 111, 112].

Potential targets for modulating intrahepatic vascular resistance in NAFLD. Schematic summary of lifestyle and pharmaceutical interventions aimed at sinusoid pathophenotypes that may contribute to the development of portal hypertension in NAFLD. While several drugs are already in clinical use for other indications, most remain in the experimental phase, and none has been approved explicitly for the prevention or reduction of portal hypertension. COX: cyclooxygenase; CSE, cystathionase; eNOS: endothelial nitric oxide synthase; KLF-2: Kruppel-like factor-2; LPS: lipopolysaccharide; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa B; PDGF: platelet-derived growth factor; PDGFR: PDGF receptor; RhoA/ROCK: Ras homolog family member A/Rho-associated coiled-coil protein kinase; sGC: soluble guanylyl cyclase; TGR5: Takeda G-protein-coupled receptor 5; TNFα: tumor necrosis factor-alpha; TXA2: thromboxane A2; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; VEGFR: VEGF receptor

Sinusoid vascular regulation is one of the promising targets of pharmacotherapy in portal hypertension, representing a dynamic component of increasing intrahepatic vascular resistance in NAFLD. While several antioxidant and anti-inflammatory drugs have been shown to improve sinusoidal microvascular dysfunction, statins stand out because of their safe clinical record and ability to modulate multiple molecular pathways involved in this process. Statins beneficially affect eNOS-NO-sGC-cGMP signaling via upregulation of KLF2, a transcription factor responsive to shear stress with eNOS being one of its gene targets, and via inhibition of the RhoA/ROCK pathway, which modulates cytoskeletal structures responsible for LSEC capillarization and promotes phosphorylation of myosin light chains leading to vasoconstriction [55, 113]. There is substantial preclinical and clinical evidence indicating the positive impact of simvastatin and other statins on microvascular function, intrahepatic vascular resistance and patient survival in cirrhosis complicated with portal hypertension [114–117].

Nuclear farnesoid X receptor (FXR) agonists represent another drug class emerging as modulators of intrahepatic vascular resistance in NAFLD and other chronic liver disease [55]. Besides repressing the rate of de novo lipogenesis [118], FXR agonists stimulate eNOS activity and inhibit contraction of stellate cells mediated by endothelin-1 [119], promote the degradation of asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), a potent eNOS inhibitor found in high levels in cirrhosis [120], and CSE, the enzyme responsible for the generation of hydrogen sulphide (H2S), a vasoactive gasotransmitter able to reduce intrahepatic vasorelaxation [121]. Moreover, combined FXR/TGR5 agonists inhibit arachidonic acid metabolism and the generation of inflammatory master switch NF-κB [122].

Regulation of erratic sinusoidal angiogenesis is a parallel goal in the management of portal hypertension with angiopoietin, VEGF and PDGF as potential major targets. Several small human studies found that sorafenib as a potent multikinase inhibitor may reduce portal hypertension in cirrhosis by blocking the activation of VEGF and PDGF receptors [123, 124]. Novel experimental approaches in rat models of cirrhosis include utilization of anti-VEGF receptor-2 monoclonal antibodies to suppress angiogenesis and ameliorate portal hypertension [125], blockage of angiopoietin-2 signaling by a chemically programmed antibody (CVX-060) to normalized hepatic microvasculature [126], and expression of dominant negative recombinant proteins that block the PDGF receptor and decrease portal venous pressure by inhibiting the activation of hepatic stellate cells [127].

Conclusion

Portal hypertension is the underlying cause of many complications that drive poor clinical outcomes in cirrhosis. Reliable assessment and monitoring of liver hemodynamics in advanced liver disease is therefore paramount. HVPG has been utilized for several decades to quantify portal hypertension, even as the technique is based on the assumption that WHVP correctly mirrors portal venous pressure. Performing HVPG measurements in patients with less advanced liver disease, such as the exceedingly prevalent noncirrhotic NAFLD, would be an impractical proposition due to inherent risks of the intervention. However, this may change with the introduction of new endoscopic techniques as we discussed above. Since portal hypertension may impact disease progression in NAFLD and is not solely the consequence of cirrhosis, it is essential to find methods that allow early detection and monitoring. We may see a conceptual change about how we perceive the pathophysiological significance of mildly increased portal pressure in NAFLD and anticipate the development of new pharmaceutical tools to prevent portal hypertension from becoming a major force behind liver-related mortality.

Abbreviations

| ADMA: | asymmetric dimethylarginine |

| CAP: | controlled attenuation parameter |

| CEC: | circulating endothelial cells |

| COX: | cyclooxygenase |

| CSE: | cystathionase |

| CSPH: | clinically significant portal hypertension |

| DAMPs: | damage-associated molecular patterns |

| DCE: | dynamic contrast material-enhanced |

| eNOS: | endothelial nitric oxide synthase |

| EUS: | endoscopic ultrasound |

| F0: | no fibrosis |

| F1: | minimal fibrosis |

| F2: | moderate fibrosis |

| F3: | advanced fibrosis |

| F4: | severe fibrosis |

| FHVP: | free hepatic venous pressure |

| FNA: | fine needle aspiration |

| FXR: | farnesoid X receptor |

| Hh: | hedgehog |

| HIF: | hypoxia-inducible factor |

| HO-1: | heme-oxygenase-1 |

| HSP-70: | heat shock protein 70 |

| HVPG: | hepatic venous pressure gradient |

| ICAM: | intercellular adhesion molecule |

| IHVR: | increased intrahepatic vascular resistance |

| IL: | interleukin |

| KLF-2: | Kruppel-like factor-2 |

| LPS: | lipopolysaccharide |

| LSEC: | liver sinusoidal endothelial cell |

| MAFLD: | metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease |

| MCP: | monocyte chemoattractant protein |

| M-CSF: | macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| MR: | magnetic resonance |

| MRE: | MR elastography |

| NAFLD: | nonalcoholic fatty liver disease |

| NF-κB: | nuclear factor kappa B |

| NO: | nitric oxide |

| PDGF: | platelet-derived growth factor |

| PDGFR: | PDGF receptor |

| PH: | portal hypertension |

| PPG: | portal pressure gradient |

| PVP: | portal venous pressure |

| RhoA/ROCK: | Ras homolog family member A/Rho-associated coiled-coil protein kinase |

| sGC: | soluble guanylyl cyclase |

| SHAPE: | subharmonic aided pressure estimation |

| TGF: | transforming growth factor-beta |

| TGR5: | Takeda G-protein-coupled receptor 5 |

| TNF: | tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| TXA2: | thromboxane A2 |

| VAP: | vascular adhesion protein |

| VCAM: | vascular cell adhesion molecule |

| VEGF: | vascular endothelial growth factor |

| VEGFR: | VEGF receptor |

| VLDL: | very low-density lipoprotein |

| WHVP: | wedged hepatic venous pressure |

Declarations

Author contributions

GB contributed conception and design of the manuscript and wrote the first draft; MR and NS wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read and approved the submitted version.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2020.