Abstract

Aim:

Angiogenesis is a universal hallmark of all cancers involving a variety of proteins including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Extensive studies have explored the potential implications of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within VEGF-A in lung cancer (LC) susceptibility, tumor growth, and their effect on the gene expression level. Accordingly, we have planned in the present study to evaluate the prevalence of the -460T/C (rs833061), the -2578C/A (rs699947), and the -2549I/D (rs35569394) SNPs and their association with clinicopathological parameters and to assess their impact on the expression of VEGF-A, VEGFR-1, and VEGFR-2 to be used in the accurate management of LC in Morocco.

Methods:

A total of 60 fresh biopsies were collected from patients with primary LC and were subjected to polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-DNA sequencing of VEGF-A to detect -460T/C (rs833061), -2578C/A (rs699947), and -2549I/D (rs35569394) SNPs. Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR was used to evaluate VEGF-A, VEGFR-1, and VEGFR-2 expression levels.

Results:

Sequencing analysis revealed the occurrence of -460T/C, -2578C/A, and -2549I/D polymorphisms with different frequencies. VEGF-2549I/D polymorphism was associated with cancer staging for both genotypes and alleles distributions (p < 0.05). Overall, gene expression analysis revealed an overexpression of VEGF-A, VEGFR-1, and VEGFR-2. The expression of VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 was significantly associated with histological types (p = 0.0114). Of note, no significant correlation was obtained between VEGF-A expression and VEGF-A gene polymorphisms (p > 0.05).

Conclusions:

This study is very informative providing the first insight into polymorphisms and expression of VEGF ligand and its receptors in LC patients from Morocco. Globally, -2549I/D SNP and VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 expressions appear to be promising prognostic biomarkers and are likely potential keys for better management of LC.

Keywords

Angiogenesis, lung cancer, polymorphisms, VEGF-A, VEGFR-1, VEGFR-2Introduction

Worldwide, lung cancer (LC) is one of the most pressing health challenge. According to the latest GLOBOCAN database, LC accounts for 12.4% of all diagnosed cases and 18.7% of all cancer deaths [1]. The development of LC is a complex, multifactorial process driven by a combination of genetic predispositions and repeated environmental exposures, two key factors that fuel its progression and worsen patient outcomes [2].

Angiogenesis is a universal hallmark of all cancers and is recognized as a critical step in tumor development, progression, and metastasis [3]. It is defined as the process through which cancer cells create their own vascular network by hijacking existing blood vessels, ensuring a constant supply of oxygen to sustain tumor growth and meet its metabolic demands, which are essential for further progression and migration to distant sites [4, 5]. In healthy tissues, the formation of new blood vessels is tightly regulated by a balance between pro- and anti-angiogenic factors. However, cancer cells exploit this delicate equilibrium, activating angiogenic signals that stimulate the creation of new blood vessel neo-vessels that are essential for the tumor’s relentless progression and its ability to metastasize [4, 6].

The vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) family is a family of secreted polypeptides acting through a family of cognate receptor kinases in endothelial cells to stimulate blood vessel formation. The VEGF family includes seven homodimeric vasoactive glycoproteins, VEGF-A, B, C, D, E, F, and placental growth factor (PLGF). VEGF-A, the founding member of the VEGF family and usually called VEGF, is located on chromosome 6p21.1 and is composed of eight exons and seven introns. Its pro-angiogenic activity involves the modulation of proliferation, migration, and survival of endothelial cells [7, 8].

The VEGF family interacts through three types of receptors: VEGFR-1, VEGFR-2, and VEGFR-3. VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 are involved in angiogenesis while VEGFR-3 is more implicated in lymphangiogenesis [8]. Currently, scientific evidence clearly shows that VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 are the major mediators of the mitogenic, angiogenic and permeability-enhancing effects of VEGF by activating the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) and phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3Ks) pathways [9].

Numerous in situ studies have shown that VEGF expression is upregulated in a wide range of cancers, including non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small cell lung cancer (SCLC) [4]. VEGF is predominantly expressed in tumor cells, which serve as its primary source, as well as in the tumor-associated stroma [10]. Targeting VEGF has emerged as a pivotal therapeutic strategy, effectively preventing tumor growth by inhibiting the formation of new blood vessels. In line with this, a variety of angiogenic inhibitors have been developed and are now widely used to block the VEGF signaling axis, thereby limiting tumor progression. Remarkably, several studies have demonstrated the impressive efficacy of combining anti-VEGF therapies with chemotherapy in the treatment of NSCLC [11–13]. Of particular interest, recent research has revealed the potential of combining angiogenesis inhibitors with immunotherapy as a late-line treatment, offering a promising strategy to enhance the management of lung adenocarcinoma patients who have developed resistance to EGFR-TKI (tyrosine kinase inhibitor) [14].

According to literature surveys, the VEGF gene is highly polymorphic, harboring over 30 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that have sparked significant research into their potential impact. These SNPs have been linked to various aspects of cancer biology, including susceptibility, tumor growth, early-stage progression, resistance to treatments, and modulation of gene expression. Among the most widely studied and prevalent of these SNPs are -460T/C (rs833061), -2578C/A (rs699947), and -2549I/D (rs35569394), located within the VEGF promoter region [15, 16]. Therefore, this study was designed to investigate the prevalence of these SNPs in a cohort of Moroccan patients with primary LC. It aims to explore their correlation with clinicopathological parameters and assess their impact on the expression levels of VEGF-A, VEGFR-1, and VEGFR-2. Additionally, the study seeks to evaluate the potential of these SNPs in improving the overall management of LC in Morocco.

Materials and methods

Patients and samples

A total of 60 patients, diagnosed with primary LC; were enrolled from the Pathology and Thoracic Surgery Departments at Ibn Rochd University Hospital in Casablanca, Morocco, between August 2019 and July 2022. Fresh biopsies were collected and immediately preserved in RNAlater® at –80℃. LC staging was performed in accordance with the 2021 World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of lung tumors.

Patient data, including age, sex, smoking history, and disease location, were obtained from the Thoracic Surgery Department’s archives. The study protocol received approval from the Ethics Committee of Ibn Rochd University Hospital (Ethical approval number: 01/20), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

DNA and RNA extractions

Genomic DNA was extracted from fresh lung biopsies using the phenol-chloroform method [17]. Total RNA was isolated from fresh frozen biopsies using TRIzol reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, Inc.), following the manufacturer’s protocol. The concentration of both extracted DNA and RNA was determined using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Single nucleotides polymorphisms assessment

The VEGF-A promoter region on chromosome 6 was selectively amplified using specific primers (Table 1). The resulting PCR products were then analyzed through capillary electrophoresis via the Sanger sequencing method, enabling precise identification of three key SNPs: -460T/C (rs833061), -2578C/A (rs699947), and -2549I/D (rs35569394).

Primers’ sequences used for VEGF-A SNPs assessment and VEGF-A, VEGFR-1, and VEGFR-2 expression analyses

| Analysis | Forward primer 5’-3’ | Reverse primer 5’-3’ | Fragment length | Chromosome position |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNPs | ||||

| -460T/C | TGTGCAGACGGCAGTCACCA | CCCGCTACCAGCCGACTTT | 588 bp | 43769749 |

| -2578C/A | ATAAGGGCCTTAGGACACCA | GCTACTTCTCCAGGCTCACA | 459 bp | 43768652 |

| -2549I/D | ATAAGGGCCTTAGGACACCA | GCTACTTCTCCAGGCTCACA | 459 bp | 43736418 |

| Expression | ||||

| β2M | GAGGCTATCCAGCGTACTCCA | CGGCAGGCATACTCATCTTTT | - | - |

| VEGF-A | AGGGCAGAATCATCACGAAGT | AGGGTCTCGATTGGATGGCA | - | - |

| VEGFR-1 | GAAAACGCATAATCTGGGACAGT | GCGTGGTGTGCTTATTTGGA | - | - |

| VEGFR-2 | GTGATCGGAAATGACACTGGAG | CATGTTGGTCACTAACAGAAGCA | - | - |

SNPs: single nucleotide polymorphisms; VEGFR-1: vascular endothelial growth factor receptor; β2M: β2 microglobulin. -: no data

PCR amplification

The PCR reaction was carried out in a total volume of 20 µL, comprising 2 μL of 10× Dream Taq Buffer, 2 μL of 10 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs, 2196131, Invitrogen), 0.6 μL of forward and reverse primers (10 μM each), 5 U/μL of Platinum Taq polymerase (XHKB1b, Invitrogen), and 2 μL of genomic DNA. A negative control, where the DNA template was omitted, was included in each reaction to ensure specificity. PCR amplification was performed using the GeneAmp PCR System (Applied Biosystems) with an initial denaturation step at 96℃ for 3 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of amplification. Each cycle consisted of a 30-second denaturation at 96℃, a 60-second primer hybridization at 60℃, and a 40-second elongation at 72°C. After the final cycle, the mixtures were incubated at 72℃ for an additional 7 minutes to ensure complete elongation. The resulting PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

PCR product purification and Sanger sequencing

The amplified fragments were first purified using the ExoSAP-IT™ PCR Product Cleanup Reagent (Applied Biosystems) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Direct sequencing was then conducted with the BigDye™ Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (catalog number: 4337455). For each sequencing reaction, 2 µL of the purified PCR product was combined with 1 µL of BigDye™ Terminator v3.1 and 0.5 µL of 10 µM forward or reverse primer, and 6.5 µL of nuclease-free water. The mixture was initially incubated at 96℃ for 1 minute, followed by 25 cycles of denaturation at 96℃ for 10 seconds, primer annealing at 50℃ for 5 seconds, and extension at 60℃ for 4 minutes. Following the sequencing reaction, products were purified using Sephadex G-50 gel-exclusion chromatography (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) to remove any residual sequencing reagents. The purified DNA was then sequenced on an ABI 3130XL DNA Analyzer, and the resulting sequences were analyzed in FASTA format and aligned with the reference gene sequence (NCBI reference sequence: NG_008732.1) using Sequencing Analysis V5.4 Software.

Evaluation of VEGF-A, VEGFR-1, and VEGFR-2 expressions

Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR tool

A total of 1 µg of each extracted RNA was used for complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis with the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (01079018, Applied Biosystems). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was then conducted in triplicate using the StepOne Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) in a final reaction volume of 10 µL. Each reaction contained 2 µL of cDNA, 5 µL of PowerUp™ SYBR™ Green Master Mix (2×), and 0.5 µL of each primer (10 µM) (Table 1) and 2 µL of Nuclease-free water. Following an initial Taq activation step at 95℃ for 2 minutes, 40 amplification cycles were carried out, each comprising a 3-second denaturation at 95℃ and a 30-second primer annealing at 60℃.

Expression levels of VEGF-A, VEGFR-1, and VEGFR-2 were normalized to the housekeeping gene β2 microglobulin (β2M), and quantification was performed using the comparative Ct method by using the following formula: 2-ΔCt formula = 2-Δ (Ct target gene – Ct reference gene).

Statistical analysis

Genotypes for each SNP were analyzed as categorical variables with three distinct groups. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Software (version 23) and GraphPad Prism (version 9). The chi-square (χ²) test was employed to assess potential associations between the mutational status of the VEGF-A gene promoter and clinicopathological factors, including cancer stage, grade, age, smoking status, and gender. To compare data across multiple groups, the Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric tests were used, depending on the nature of the data. A significance threshold of p < 0.05 was applied to all statistical tests, with results labeled by an asterisk (*) to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Study population characteristics

In this study, a total of 60 LC patients were recruited, 46 were male and only 14 were female, with a sex ratio of 3.29. Clinicopathological characteristics of recruited patients are summarized in Table 2. The mean age of patients was 59.93 years, ranging from 31 to 83 years. Most patients were active smokers (70%) and were all men. Secondhand tobacco smoking was observed in 3.3%. Anatomopathological analysis showed that adenocarcinoma prevails and was reported in 56.7% of cases, followed by squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) identified in 21.7% of cases. At clinical level, most patients were at stage III (31.7%), patients at stages I and II were reported in 26.7% and 28.3% of cases, respectively, and only 10% of our patients were at stage IV.

Clinicopathological of recruited patients

| Variables | Number of patients | Percentages (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 46 | 76.7 |

| Female | 14 | 23.3 | |

| Age | < 60 years | 30 | 50.0 |

| ≥ 60 years | 30 | 50.0 | |

| Tobacco smoking | Yes | 42 | 70.0 |

| No | 18 | 30.0 | |

| Histological type | ADK | 34 | 56.7 |

| SCC | 13 | 21.7 | |

| LCLC | 1 | 1.7 | |

| PSC | 1 | 1.7 | |

| NET | 6 | 10.0 | |

| MH | 3 | 5.0 | |

| Unknown | 2 | 3.3 | |

| TNM staging | I | 16 | 26.7 |

| II | 17 | 28.3 | |

| III | 19 | 31.7 | |

| IV | 6 | 10.0 | |

| Unknown | 2 | 3.3 | |

ADK: adenocarcinomas; SCC: squamous cell carcinoma; LCLC: large cell lung carcinoma; PSC: pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma; NET: neuroendocrine tumors; MH: mixed histology; TNM: tumor-node-metastasis

Genotype and allelic frequencies distribution of VEGF-A polymorphisms

Sequencing analysis revealed the occurrence of three SNPs: -460T/C (rs833061), -2578C/A (rs699947), and -2549I/D (rs35569394) with different frequencies (Table 3). The most frequent genotype for the rs833061 SNP was CT, reported in 46.7% of cases. At allelic level, the C allele was found in 53.3% of cases and the T allele in 46.7%. Concerning the rs699947 SNP, the AC genotype prevails and was identified in 46.7% of cases. At allelic level, the C allele was detected in 56.7% of cases and the A allele in 43.3% of cases. For the rs35569394 SNP, data analysis showed the predominance of the ID genotype, identified in 41.7% of cases. Alleles harboring the insertion represent 44.2% and those with the deletion represent 55.8% of total alleles.

Genotypic and allelic frequency distributions of VEGF-A polymorphisms

| Parameter | rs833061 (-460 T/C) | Parameter | rs699947 (-2578 C/A) | Parameter | rs35569394 (-2549 I/D) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotypes | N | % | Genotypes | N | % | Genotypes | N | % |

| CC | 18 | 30 | AA | 12 | 20 | II | 14 | 23.3 |

| CT | 28 | 46.7 | AC | 28 | 46.7 | ID | 25 | 41.7 |

| TT | 14 | 23.3 | CC | 20 | 33.3 | DD | 21 | 35 |

| Alleles | N | % | Alleles | N | % | Alleles | N | % |

| C | 64 | 53.3 | A | 52 | 43.3 | I | 53 | 44.2 |

| T | 56 | 46.7 | C | 68 | 56.7 | D | 67 | 55.8 |

Of particular interest, all patients with AA genotype at locus -2578 harbored the insertion at locus -2549 at homozygous status. Moreover, the presence of C allele is strongly associated with the presence of the deletion, suggesting a close association between -2578C/A and -2549I/D (p = 0.001). Notably, the minor allele frequencies for these SNPs were 46.7%, 43.3%, and 44.2%.

Association of VEGF-A polymorphisms and clinicopathological features of LC patients

In this study, we have also investigated the relationship between the clinicopathological characteristics of LC patients and the genotypes and alleles frequencies of the VEGF-A polymorphisms -460T/C, -2578C/A, and -2549I/D, and results are presented in Tables 4, 5, and 6, respectively. For VEGF-2549I/D polymorphism, data analysis showed a significant association between the SNP and cancer staging for both genotypes and alleles distributions (p < 0.05). For the other parameters, no significant association was obtained. For -460T/C and -2578C/A SNPs, no statistically significant association was obtained between these SNPs and the clinicopathological features (p > 0.05).

Clinicopathological characteristics of LC patients and the genotype and allele frequencies of -460T/C polymorphism

| Parameter | N | Genotype | Allele | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC (%) | CT (%) | TT (%) | p | C (%) | T (%) | p | ||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 46 | 16 (34.8) | 20 (43.5) | 10 (21.7) | 0.34 | 52 (56.5) | 40 (43.5) | 0.20 |

| Female | 14 | 2 (14.3) | 8 (57.1) | 4 (28.6) | 12 (42.9) | 16 (57.1) | ||

| Age | ||||||||

| ≤ 50 | 10 | 4 (40.0) | 5 (50.0) | 1 (10.0) | 0.51 | 13 (65.0) | 7 (35.0) | 0.25 |

| > 50 | 50 | 14 (28.0) | 23 (46.0) | 13 (26.0) | 51 (51.0) | 49 (49.0) | ||

| Smoking | ||||||||

| Yes | 42 | 15 (35.7) | 18 (42.9) | 9 (21.4) | 0.34 | 48 (57.1) | 36 (42.9) | 0.20 |

| No | 18 | 3 (16.7) | 10 (55.5) | 5 (27.8) | 16 (44.4) | 20 (55.6) | ||

| Stage | ||||||||

| I | 16 | 3 (18.7) | 9 (56.3) | 4 (25.0) | 0.80 | 15 (46.9) | 17 (53.1) | 0.45 |

| II | 17 | 6 (35.3) | 8 (47.1) | 3 (17.6) | 20 (58.8) | 14 (41.2) | ||

| III | 19 | 8 (42.1) | 7 (36.8) | 4 (21.1) | 23 (60.5) | 15 (39.5) | ||

| IV | 6 | 1 (16.7) | 3 (50.0) | 2 (33.3) | 5 (41.7) | 7 (58.3) | ||

| Unknown | 2 | 0 | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 1 (25.0) | 3 (75.0) | ||

| Histological type | ||||||||

| ADK | 34 | 12 (35.3) | 15 (44.1) | 7 (20.6) | 0.71 | 39 (57.3) | 29 (42.7) | 0.82 |

| SCC | 13 | 4 (30.8) | 5 (38.5) | 4 (30.8) | 13 (50.0) | 13 (50.0) | ||

| LCLC | 1 | 0 | 1 (100.0) | 0 | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | ||

| PSC | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (100.0) | 0 | 2 (100.0) | ||

| NET | 6 | 1 (16.7) | 4 (66.7) | 1 (16.7) | 6 (50.0) | 6 (50.0) | ||

| MH | 3 | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 3 (50.0) | 3 (50.0) | ||

| Unknown | 2 | 0 | 2 (100.0) | 0 | 2 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) | ||

ADK: adenocarcinomas; SCC: squamous cell carcinoma; LCLC: large cell lung carcinoma; PSC: pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma; NET: neuroendocrine tumors; MH: mixed histology; LC: lung cancer

Clinicopathological characteristics of LC patients and the genotype and allele frequencies of -2578C/A polymorphism

| Parameter | N | Genotype | Allele | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA (%) | AC (%) | CC (%) | p | A (%) | C (%) | p | ||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 46 | 10 (21.7) | 22 (47.8) | 14 (30.4) | 0.65 | 42 (45.7) | 50 (54.3) | 0.35 |

| Female | 14 | 2 (14.3) | 6 (42.9) | 6 (42.9) | 10 (35.7) | 18 (64.3) | ||

| Age | ||||||||

| ≤ 50 | 10 | 2 (20.0) | 4 (40.0) | 4 (40.0) | 0.87 | 8 (40.0) | 12 (60.0) | 0.74 |

| > 50 | 50 | 10 (20.0) | 24 (48.0) | 16 (32.0) | 44 (44.0) | 56 (56.0) | ||

| Smoking | ||||||||

| Yes | 42 | 10 (23.8) | 20 (47.6) | 12 (28.6) | 0.37 | 40 (47.6) | 44 (52.4) | 0.15 |

| No | 18 | 2 (11.1) | 8 (44.4) | 8 (44.4) | 12 (33.3) | 24 (66.7) | ||

| Stage | ||||||||

| I | 16 | 1 (6.3) | 8 (50.0) | 7 (43.8) | 0.25 | 10 (31.3) | 22 (68.8) | 0.12 |

| II | 17 | 5 (29.4) | 5 (29.4) | 7 (41.2) | 15 (44.1) | 19 (55.9) | ||

| III | 19 | 5 (26.3) | 11 (57.9) | 3 (15.8) | 21 (55.3) | 17 (44.7) | ||

| IV | 6 | 0 | 3 (50.0) | 3 (50.0) | 3 (25.0) | 9 (75.0) | ||

| Unknown | 2 | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 0 | 3 (75.0) | 1 (25.0) | ||

| Histological type | ||||||||

| ADK | 34 | 7 (20.6) | 16 (47.1) | 11 (32.4) | 0.88 | 30 (44.1) | 38 (55.9) | 0.89 |

| SCC | 13 | 3 (23.1) | 6 (46.2) | 4 (30.8) | 12 (46.2) | 14 (53.8) | ||

| LCLC | 1 | 0 | 1 (100.0) | 0 | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | ||

| PSC | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (100.0) | 0 | 2 (100.0) | ||

| NET | 6 | 1 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) | 3 (50.0) | 4 (33.3) | 8 (66.7) | ||

| MH | 3 | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 3 (50.0) | 3 (50.0) | ||

| Unknown | 2 | 0 | 2 (100.0) | 0 | 2 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) | ||

ADK: adenocarcinomas; SCC: squamous cell carcinoma; LCLC: large cell lung carcinoma; PSC: pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma; NET: neuroendocrine tumors; MH: mixed histology; LC: lung cancer

Clinicopathological characteristics of LC patients and the genotype and allele frequencies of -2549I/D alterations

| Parameter | N | Genotype | Allele | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| II (%) | ID (%) | DD (%) | p | I (%) | D (%) | p | ||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 46 | 12 (26.1) | 19 (41.3) | 15 (32.6) | 0.62 | 43 (46.7) | 49 (53.3) | 0.30 |

| Female | 14 | 2 (14.3) | 6 (42.9) | 6 (42.9) | 10 (35.7) | 18 (64.3) | ||

| Age | ||||||||

| ≤ 50 | 10 | 2 (20.0) | 4 (40.0) | 4 (40.0) | 0.93 | 8 (40.0) | 12 (60.0) | 0.68 |

| > 50 | 50 | 12 (24.0) | 21 (42.0) | 17 (34.0) | 43 (43.0) | 57 (57.0) | ||

| Smoking | ||||||||

| Yes | 42 | 12 (28.6) | 17 (40.5) | 13 (31.0) | 0.31 | 41 (48.8) | 43 (51.2) | 0.12 |

| No | 18 | 2 (11.1) | 8 (44.4) | 8 (44.4) | 12 (33.3) | 24 (66.7) | ||

| Stage | ||||||||

| I | 16 | 1 (6.3) | 9 (56.3) | 6 (37.5) | 0.01 | 11 (34.4) | 21 (65.6) | 0.01 |

| II | 17 | 5 (29.4) | 5 (29.4) | 7 (41.2) | 15 (44.1) | 19 (55.9) | ||

| III | 19 | 6 (31.6) | 10 (52.6) | 3 (15.8) | 22 (57.9) | 16 (42.1) | ||

| IV | 6 | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 5 (83.3) | 1 (8.3) | 11 (91.7) | ||

| Unknown | 2 | 2 (100.0) | 0 | 0 | 4 (100.0) | 0 | ||

| Histological type | ||||||||

| ADK | 34 | 8 (23.5) | 15 (44.1) | 11 (32.4) | 0.67 | 31 (45.6) | 37 (54.4) | 0.82 |

| SCC | 13 | 4 (30.8) | 5 (38.5) | 4 (30.8) | 13 (50.0) | 13 (50.0) | ||

| LCLC | 1 | 0 | 1 (100.0) | 0 | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | ||

| PSC | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (100.0) | 0 | 2 (100.0) | ||

| NET | 6 | 1 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) | 3 (50.0) | 4 (33.3) | 8 (66.7) | ||

| MH | 3 | 1 (33.3) | 0 | 2 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) | 4 (66.7) | ||

| Unknown | 2 | 0 | 2 (100.0) | 0 | 2 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) | ||

ADK: adenocarcinomas; SCC: squamous cell carcinoma; LCLC: large cell lung carcinoma; PSC: pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma; NET: neuroendocrine tumors; MH: mixed histology; LC: lung cancer

VEGF-A, VEGFR-1, and VEGFR-2 gene expressions

Based on the median values obtained from the 2-ΔCt formula, patients were classified into two categories: patients with low expression and patients with high expression for the VEGF-A ligand as well as VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 receptors. The results are summarized in Table 7.

The expression level of VEGF-A, VEGFR-1, and VEGFR-2 genes

| Gene | Expression level | Number of cases (%) |

|---|---|---|

| VEGF-A | Low expression | 37 (61.7%) |

| High expression | 23 (38.3%) | |

| VEGFR-1 | Low expression | 41 (68.3%) |

| High expression | 19 (31.7%) | |

| VEGFR-2 | Low expression | 41 (68.3%) |

| High expression | 19 (31.7%) |

Patients with a value of 2-ΔCt inferior to the median are considered as low expressed for the corresponding gene and vice versa

The association between the VEGF-A expression and clinicopathological features

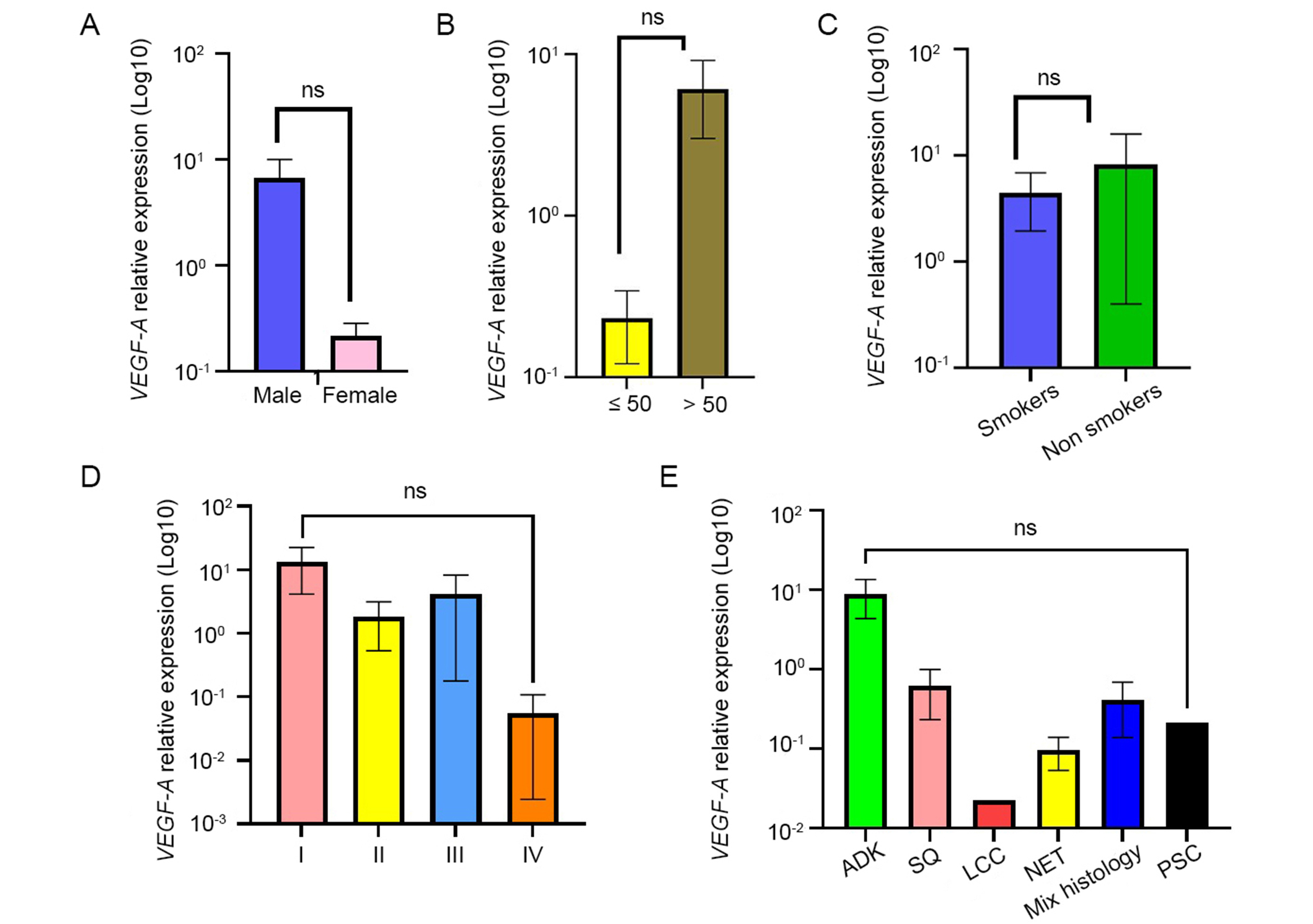

The effect of VEGF-A expression on clinicopathological features was assessed and results are displayed in Figure 1. Overall, an overexpression of VEGF-A was observed in patients aged more than 50 years (p > 0.05). Higher expression is also observed in males with no significant association. On the other hand, great variation of VEGF-A expression was obtained according to the clinical stage and histological types, but the differences were not statistically significant.

Association between VEGF-A expression level and the clinicopathological features. Results were presented as the mean ± SD. (A) Sex; (B) age; (C) smoking status; (D) clinical stage; (E) histological type. ns: not significant (p values ≥ 0.05). ADK: adenocarcinomas; SQ: squamous cell carcinoma; LCC: large cell carcinoma; NET: neuroendocrine tumors; PSC: pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma

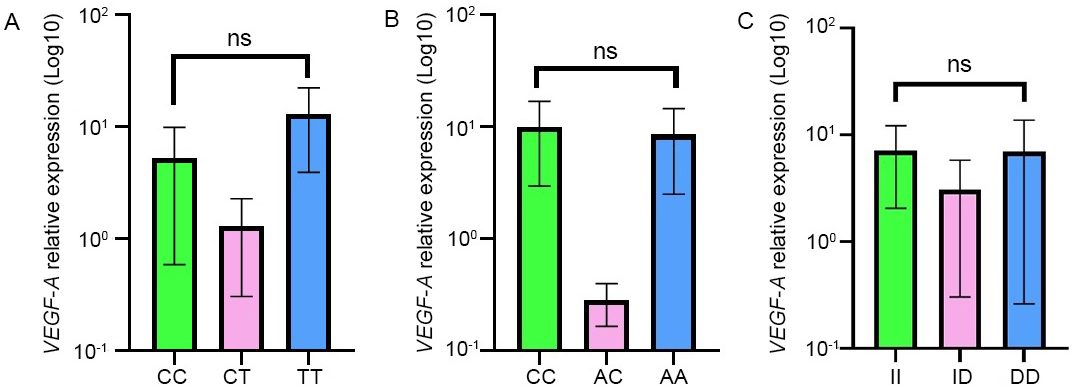

Association between the VEGF-A SNPs and expression

The impact of VEGF-A gene polymorphisms on VEGF-A expression was also evaluated and the results are reported in Figure 2. Of particular interest, for the 3 SNPs, VEGF-A expression was found to be lower in patients with the heterozygous genotypes. Regarding the -460T/C SNP, the homozygous TT genotype was found to be higher than the homozygous CC. For the other SNPs, -2578C/A and -2549I/D, the expression level of VEGF-A was almost the same between the two homozygous genotypes. Statistical analysis revealed no significant correlation between VEGF-A expression and VEGF gene polymorphisms (p > 0.05).

Association between VEGF-A expression and the VEGF-A genotypes relative to -460T/C (A), -2578C/A (B), and -2549I/D (C) SNPs. Results were presented as the mean ± SD. ns: not significant (p values ≥ 0.05)

The association between the expression of VEGFR-1/-2 and the clinicopathological characteristics of LC patients

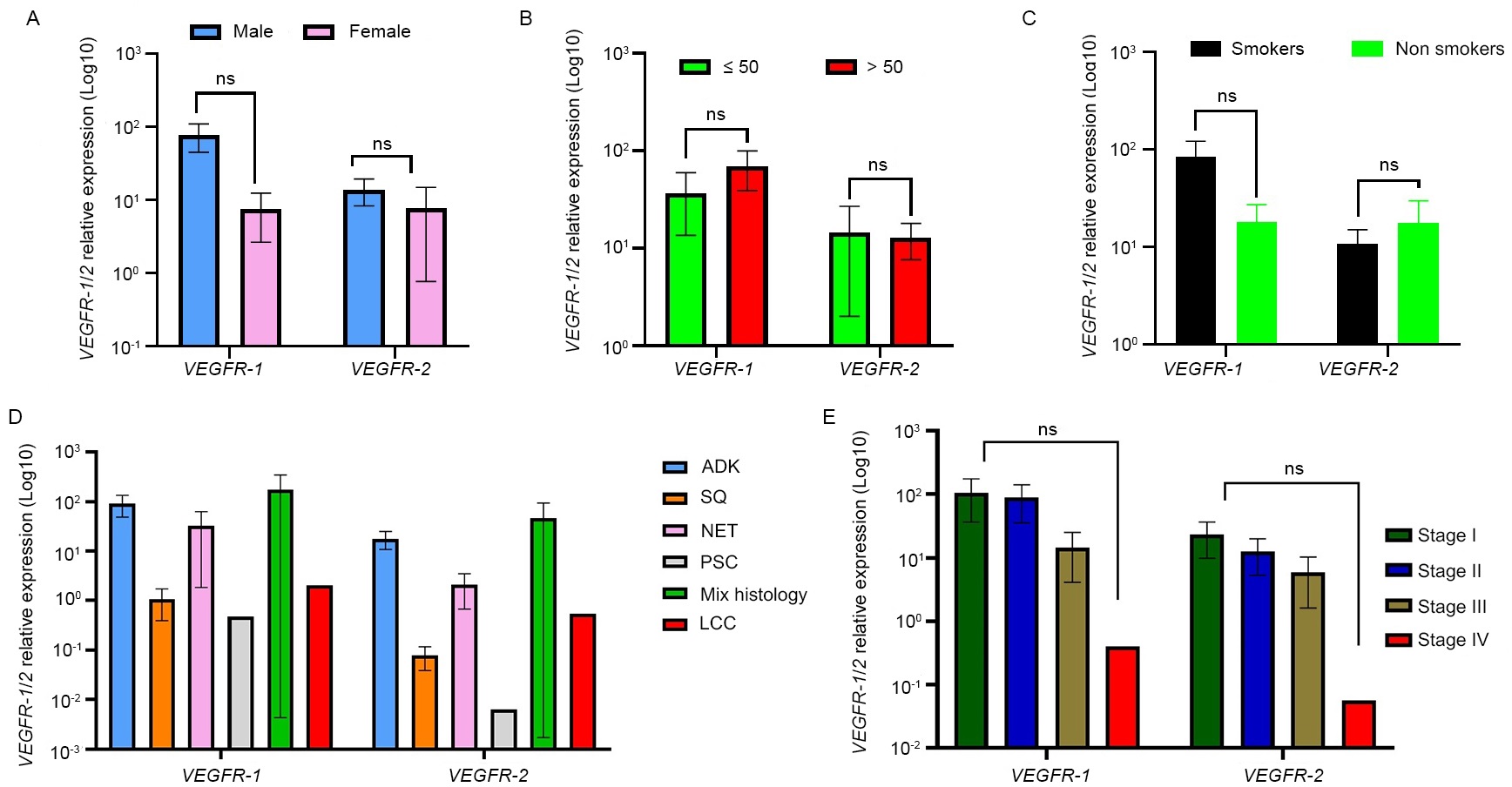

In this study, we have also investigated the impact of VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 expressions on the clinicopathological features of LC cases and findings are shown in Figure 3. Globally, no significant association was obtained between VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 expressions and gender, age, smoking status, and clinical staging (p > 0.05) even though the expression of VEGFR-1 seems to be higher in male patients, smokers, patients above 50 years old and in early stages whereas expression of VEGFR-2 seems to be rather higher in patients under 50 years old and non-smokers.

Association between VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 expressions and clinicopathological features. Results were presented as the mean ± SD. (A) Sex; (B) age; (C) smoking status; (D) histological type; (E) clinical stage. ns: not significant (p values ≥ 0.05). ADK: adenocarcinomas; SQ: squamous cell carcinoma; LCC: large cell carcinoma; NET: neuroendocrine tumors; PSC: pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma

Interestingly, the expression of VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 was significantly associated with histological types (p = 0.0114). Indeed, a higher expression of both receptors was reported in patients with adenocarcinomas and neuroendocrine tumors.

Discussion

During the last decades, extensive studies explored in-depth tumor angiogenesis along with genes involved for their potential use as biomarkers for better cancer management and/or as therapeutic targets to limit tumor growth and progression. In this field, many studies have focused on the impact of VEGF family and their specific receptors, mainly VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2, in cancer development and progression. Accordingly, VEGF-A functional SNPs, including -460T/C, -2578C/A, and -2549I/D, and their implications in cancer have been investigated in a wide range of studies. In the present study, data analysis revealed the occurrence of three polymorphisms: -460T/C (rs833061), -2578C/A (rs699947), and -2549I/D (rs35569394) with different frequencies in LC cases from Morocco.

Of particular interest, a significant association was found between -2549I/D SNP and clinical staging of LC cases. For the other clinicopathological characteristics, no significant association was obtained. Moreover, no statistically significant association was found between -460T/C and -2578C/A, and all clinicopathological features. The association between these SNPs and clinical and/or pathological parameters has been widely studied and results are very controversial. Liu et al. [18, 19] have reported the absence of any significant association between VEGF-2578C/A and -460T/C SNPs, and the risk of LC. Likewise, Yang et al. [20] have shown in a meta-analysis study on the Asian population that VEGF-460T/C and -2578C/A SNPs are not associated with the risk of LC development. However, in a study conducted by Li et al. [21] and Naykoo et al. [22], the association between LC susceptibility and VEGF-2578C/A SNP was well established. A meta-analysis performed by Song et al. [23] showed that the -2578C/A polymorphism may increase the risk of LC, especially in smoker and/or SCC patients, whereas in nonsmoker patients and SCC patients with -460T/C polymorphism, the risk of LC was decreased.

The association between these SNPs and clinicopathological features was assessed also in other cancers. In this field, no specific association was found between -2578C/A and gender, age, and histological subtype within non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma patients [24]. Moreover, non-correlation between VEGF polymorphisms and clinicopathological characteristics was reported in bladder cancer cases [25, 26].

It’s important to highlight that our statistical analysis uncovered an association between the -2549I/D polymorphism and clinical stage (p < 0.01). Recently, a case-control study showed that VEGF-2549I/D was significantly associated with the clinical stages of esophageal cancer and interestingly patients with -2549I/D genotype had a better response to chemotherapy [27]. These results highlight the interest of this biomarker in cancer staging and the relevance of looking for this SNP for better monitoring the disease.

In this study, a strong association was found between -2578C/A and -2549I/D SNPs. This association is a result of linkage disequilibrium between the two loci, mainly due to dependent segregation given the small distance between the two loci. The association between -2578C/A and -2549I/D SNPs has already been reported and documented in many diseases including chronic liver disease [28], Alzheimer’s [29], and bladder cancer [25, 30].

In this study, the association between VEGF-A expression and clinicopathological parameters was also investigated and showed no significant difference according to the patient’s age and smoking status, and the absence of any association regarding the clinical staging and pathological grades. These results are in agreement with most published data that converge to the absence of a significant association between VEGF-A expression and clinicopathological features [9, 31]. In contrast, other studies have reported a significant variation in VEGF-A expression in LC cases. In this field, Bonnesen et al. [32] have found that histological subgroups of NSCLC express VEGF-A differently, with increased expression in adenocarcinomas compared to SCC. Moreover, high level of VEGF-A expression was significantly associated with stage IV of LC [4]. Other studies on large sampling are needed to explore in-depth the association between gene expression and both histological grades and clinical staging.

On the other hand, the impact of -2578C/A and -2549I/D SNPs on VEGF-A expression was also evaluated and results clearly showed that these SNPs don’t have any control on the gene expression; the nature and/or the position of these SNPs don’t alter genetic transcription process.

The activity of VEGF-A ligand is mediated by binding to and activating membrane receptors with tyrosine-kinase activity (RTKs), VEGFR-1, and VEGFR-2. A transcriptomic analysis of the mRNA encoding these receptors was assessed in order to ascertain the level of expression of the VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2, and to establish the correlation between their expressions and the clinicopathological characteristics of the LC patients. In this study, VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 were well expressed and a significant difference was observed with histological grades; the expression being higher in patients with adenocarcinomas and neuroendocrine tumors.

No significant association was found between VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 and gender, age, and smoking status, which are in agreement with already published data [15, 33, 34]. In the current study, a higher expression of VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 was noted in stages I, II, and III, and a low expression of both receptors in stage IV, with no statistically significant correlation. Even this result is supported by Bonnesen et al. [32] who have reported no significant correlation between VEGFR-2 expression and LC stage at diagnosis; it remains similar to that of Ding et al. [34] who showed that VEGFR-2 is down-expressed in advanced stages and reported significant correlation of VEGFR-2 expression and clinical tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage.

Although VEGFR-1 mostly functions as a decoy receptor, it can also be expressed in cancer cells, where it contributes to the proliferation and survival of tumor cells. Moreover, by attracting monocytes and macrophages, the signaling initiated by VEGFR-1 can promote the synthesis of matrix metalloproteinase-9 and aid in the metastasis of tumors [35].

Scientific evidence has clearly shown that patients with high expression levels of VEGFR-1, VEGFR-2, and VEGF-A had significantly shorter survival than patients who expressed only one receptor type and/or had low VEGF-A level [36], suggesting that these biomarkers are predictive of LC prognosis and may be considered as a prominent target of anti-angiogenic drugs for better management of this devastating disease.

SNPs in VEGF gene are known to be predictive and prognostic markers for major solid tumors including NSCLC, colorectal, and prostate cancers [37]. The prognostic role of functional VEGF SNPs depends on tumor histology [38]. Also, SNPs in VEGF gene may affect survival outcomes among early-stage (NSCLC) patients [39].

Overall, the study is very conclusive and clearly showed the limited interest in using -460T/C and -2578C/A in LC management. However, a promising role of -2549I/D SNP in LC staging and therapy has been highlighted which must be studied in depth for personalized medicine strategy. The study also suggested that the expression of the VEGF-A, VEGFR-1, and VEGFR-2 genes may be useful biomarkers and promising therapeutic targets for LC management. However, this study has some limitations mainly the relatively small number of patients and lack of follow-up data to predict clinical outcomes.

To sum up, VEGF-A-2549I/D SNP significantly influences clinical staging, with the allele carrying the deletion strongly associated with more advanced stages, making this SNP a promising biomarker for LC prognosis. Additionally, expressions of VEGFR-1, VEGFR-2, and VEGF-A are elevated, with VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 expressions showing significant associations with LC staging. These findings suggest that these markers could serve as valuable prognostic biomarkers. Therefore, further investigation of the -2549I/D SNP and the evaluation of VEGF-A, VEGFR-1, and VEGFR-2 expressions hold great potential as biomarkers for improved LC management.

Abbreviations

| cDNA: | complementary DNA |

| LC: | lung cancer |

| NSCLC: | non-small cell lung cancers |

| PCR: | polymerase chain reaction |

| RT-PCR: | reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction |

| SCC: | squamous cell carcinoma |

| SCLC: | small cell lung cancers |

| SNPs: | single nucleotide polymorphisms |

| VEGF: | vascular endothelial growth factor |

| VEGFR-1: | vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 |

| WHO: | World Health Organization |

Declarations

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Department of Thoracic Surgery staff for patient recruitment and fresh tissues collection. We also thank the General Laboratory of Pathological Anatomy physicians for anatomopathological examination.

Author contributions

YE: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing—original draft. SH, MK, SB, and MR: Data curation, Writing—review & editing. HD and FG: Writing—review & editing. MA and ME: Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing. IC: Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing, Supervision. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by Ethics Committee of the Ibn Rochd University Hospital (Ethical approval number: 01/20).

Consent to participate

Informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from all participants.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The prospective data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (Imane Chaoui, im_chaoui@yahoo.fr) upon reasonable request.

Funding

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

Publisher’s note

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.