Abstract

Aim:

Psoriasis is a common chronic inflammatory skin disorder, which has adverse effects on patients’ quality of life. Natural products exhibit significant therapeutic capacities with small side effects and might be preferable alternative treatments for patients with psoriasis. This study summarizes the signaling pathways with the potential targets of natural products and their efficacy for psoriasis treatment.

Methods:

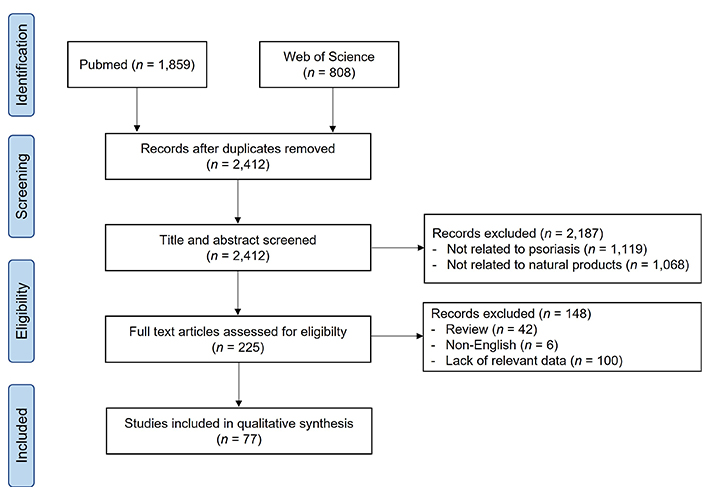

The literature for this article was acquired from PubMed and Web of Science, from January 2010 to December 2020. The keywords for searching included “psoriasis” and “natural product”, “herbal medicine”, “herbal therapy”, “medicinal plant”, “medicinal herb” or “pharmaceutical plant”.

Results:

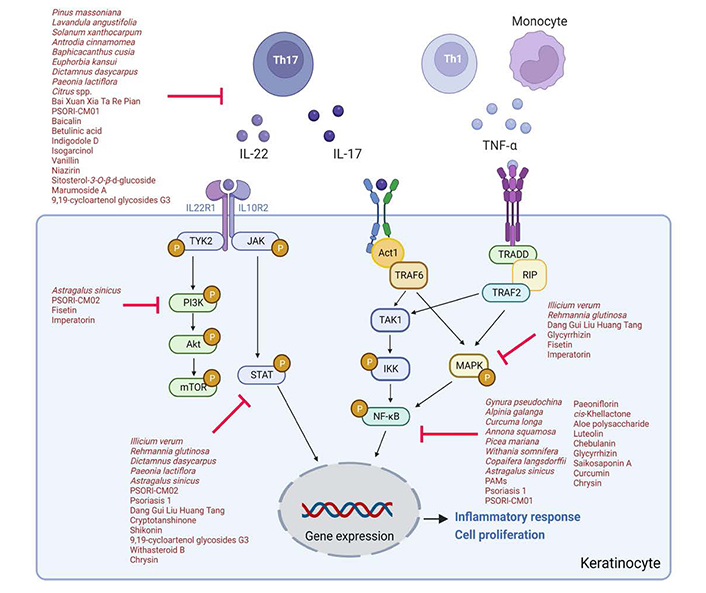

Herbal extracts, natural compounds, and herbal prescriptions could regulate the signaling pathways to alleviate psoriasis symptoms, such as T helper 17 (Th17) differentiation, Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT), nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), and other signaling pathways, which are involved in the inflammatory response and keratinocyte hyperproliferation. The anti-psoriatic effect of natural products in clinical trials was summarized.

Conclusions:

Natural products exerted the anti-psoriatic effect by targeting multiple signaling pathways, providing evidence for the investigation of novel drugs. Further experimental research should be performed to screen and characterize the therapeutic targets of natural products for application in psoriasis treatment.

Keywords

Natural products, herbal medicine, psoriasis, mechanism, signaling pathway, targetIntroduction

Psoriasis is a chronic, immune-mediated inflammatory skin disorder characterized by hyperproliferation and disrupted differentiation of keratinocytes and skin infiltration of inflammatory cells, leading to the formation of erythematous, scaly, and thickened plaques on skin lesions [1]. The psoriatic plaques symmetrically distribute with major occurrence on the extensor areas of elbows and knees, on the scalp, but also can appear on any skin surface of the body [2]. Psoriasis is one of the most common human skin diseases that affects 2–3% of the global population and the prevalence varies among different regions with the highest rate of approximately 11% in some European countries [3–5]. A variety of comorbidities associated with psoriasis have been reported, including psychological disorders, arthritis, and cardiovascular diseases that significantly reduced the quality of life of the patients [6].

Psoriasis has been considered a multifactorial disease with the pathogenesis remains unclear. However, accumulating evidence has suggested that the complex interaction of genetic, immunological, and environmental factors plays a crucial role in the initiation as well as the progression of psoriasis [1]. In the early stage, peripheral dendritic cells (DCs) are recruited into skin lesions. In response to environmental stimuli, keratinocytes secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, which are involved in the activation of DCs in the dermis [7]. Subsequently, activated DCs produce various inflammatory mediators such as IL-12 and IL-23, to trigger the differentiation of naive T cells into T helper 1 (Th1) and Th17 cells. In turn, Th1 and Th17 also secrete TNF-α, interferon (IFN)-γ, IL-17, and IL-22, which have feedback to DCs. These pro-inflammatory molecules promote keratinocyte hyperproliferation and maintain chronic skin inflammation, which are hallmarks of psoriasis [8]. Apart from lymphocytes, monocytes and macrophages also play a role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis [9, 10]. The population of monocytes/macrophages was increased in the psoriatic skin lesions, compared to normal skin. These cells can produce IL-17 and TNF-α in response to cytokine stimulation, demonstrating their roles in skin inflammation in psoriasis [9].

Psoriasis is an incurable disease; therefore, all available therapeutic approaches target alleviating skin manifestation of this disease. Treatments of psoriasis include topical application, systemic administration, and phototherapy. Corticosteroids (such as dexamethasone, clobetasol) and vitamin D analogs (tacalcitol, calcitriol) are the most common topical agents used to treat psoriasis by reducing inflammation, itching, and improving psoriatic scales [11, 12]. Oral administration of immunosuppressants (cyclosporine, methotrexate) or retinoids (acitretin) has shown beneficial effects on psoriasis symptoms by inhibiting inflammation and excessive proliferation of keratinocytes [13]. Recently, various biological drugs have been used in the management of psoriasis, including IL-17 inhibitors (secukinumab, brodalumab), IL-23 inhibitor (ustekinumab, tildrakizumab), or TNF-α inhibitors (infliximab, certolizumab), which directly target key molecules in the pathogenesis of psoriasis to inhibit the progression of the disease [14, 15]. Phototherapy is often suggested as an additional therapy for higher treatment outcomes [16]. However, all these therapies are associated with various adverse effects, leading to low satisfaction from the patients. For example, long-term application of steroids results in skin atrophy, susceptibility to infection, and risk of psychiatric disorders [17]. Patients who experienced low-dose long-term treatment of methotrexate might be suffered from liver and gastric abnormalities, bone marrow suppression, and hair loss [18]. Biologics such as secukinumab also have several side effects, including nasopharyngitis and upper respiratory tract infection [19]. This evidence raises concerns about alternative therapeutic approaches with fewer side effects for psoriasis management.

Natural products or herbal medicines have been traditionally used to treat various chronic diseases for centuries, including psoriasis. In comparison with synthetic drugs, natural products exhibit fewer side effects, therefore they are preferable alternative treatments for patients with psoriasis. Approximately 50% of psoriasis patients in Southern Europe have used natural medicine during their treatment, this prevalence is up to 60% of patients in Asian countries [20, 21]. Herbal products possess a variety of bioactive components with a diversity of structures, pharmacological activities, and multiple mechanisms of action, leading to their potentials for an effective treatment, which cannot be observed in synthetic drugs [22]. Moreover, natural products are considered cost-effective and safe for patients. Therefore, studies employing herbal medicines for anti-psoriatic activity are still conducted to investigate new alternative treatments for psoriasis. This review aims to summarize the potential signaling pathways and targets, as well as the efficacy of natural products in the treatment of psoriasis based on the results from both preclinical and clinical studies.

Materials and methods

PubMed and Web of Science databases were used for searching the literature published from January 2010 to December 2020 for this review article. The keywords included “psoriasis” and “natural product”, “herbal medicine”, “herbal therapy”, “medicinal plant”, “medicinal herb” or “pharmaceutical plant”.

Inclusion criteria include clinical studies using natural products (herbs, natural compounds, herbal formula) with placebo or drug control treatment and preclinical studies demonstrated effects and target signaling pathways of natural products in psoriasis treatment. The flow chart of this study is shown in Figure 1.

Results

Signaling pathways and targets of natural products related to psoriasis

Various signaling pathways have been demonstrated to play a role in the development of psoriasis. The effects of natural products, including herbs, natural compounds, and herbal formulas on psoriasis-related signaling pathways are shown in Tables 1–3.

The effects of extracts on psoriasis

| Plant | Used part | Extract method | In vitro | In vivo | Signaling pathway(s) | Target(s) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actinidia arguta | Fruit | Water | HaCaT | Mice | NF-κB; STAT | IL-17 | [87] |

| Alpinia galanga | Rhizome | EtOH | HaCaT | - | NF-κB | IL-8, CD40, CSF1 | [45] |

| Annona squamosa | Leaf | ||||||

| Curcuma longa | Rhizome | ||||||

| Antrodia cinnamomea | Fruit | EtOH | T cells | Mice | Th17 cell differentiation | IL-17A, IL-21, IL-22, TNF-α | [30] |

| Artemisia capillaris | Whole part | EtOH | HaCaT | Mice | Apoptosis | Ki67, ICAM-1 | [103] |

| Astragalus sinicus L. | Root | MeOH/CH2Cl2 | HaCaT; T cells | Mice | NF-κB; JAK/STAT; PI3K/Akt | IL-17, IL-22, IL-10 | [86] |

| Baphicacanthus cusia (Ness) Bremek | Aerial part | - | aHK; HMEC-1; Jurkat T; U937 | Mice | Th17 cell differentiation | S100A9, IL-6, IL-8, CCL20 | [31] |

| Copaifera langsdorffii Desf. | Oleoresin | - | THP-1 | - | NF-κB | IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α | [46] |

| Datura metel L. | Flower | EtOH | - | Mice | TLR7/8–MyD88– NF-κB–NLRP3 inflammasome | IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, IL-17, IL-22, IL-23, TNF-α, MCP-1 | [89] |

| Dictamnus dasycarpus Turcz. | Root bark | MeOH | - | Mice | STAT3; Th17 cell differentiation | IL-17, IFN-γ | [72] |

| Euphorbia kansui | Root | MeOH | T cells | Mice | Th17 cell differentiation | IL-17, IL-22, IL-23, IL-12 | [32] |

| Gynura pseudochina (L.) | Leaf | EtOH | HaCaT | - | NF-κB | IL-8 | [44] |

| Illicium verum Hook. f. | Fruit | EtOH | HaCaT | - | JAK/STAT | ICAM-1 | [60] |

| Lavandula angustifolia | Essential oil | - | - | Mice | Th17 cell differentiation | IL-17, IL-22, TNF-α, IL-1β | [28] |

| Picea mariana | Cortex | Water | Keratinocytes | - | NF-κB | ICAM-1, IL-6, IL-8, NO | [47] |

| Pinus massoniana | Rosin | Water | Splenocytes | Mice | Th17 cell differentiation | IL-17, IL-22, IL-23, TNF-α, K17, PCNA | [27] |

| Rehmannia glutinosa | Root | EtOH | - | Mice | JAK/STAT | TNF-α, IL-6, IL-23, IL-17 | [61] |

| Salvia miltiorrhiza | Root | - | HaCaT | Mice | Hippo | Caspase-3, Bcl-2, BAX, p53, p21 | [105] |

| Sinapis Alba Linn | Seed | - | - | Mice | NLRP3 inflammasome | IL-1β, IL-18, caspase-1, ASC | [88] |

| Splenocytes | NF-κB | IL-17, IL-22, IFN-α, iNOS | [90] | ||||

| Solanum xanthocarpum | Stem | EtOH | - | Mice | Th17 cell differentiation | TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-17 | [29] |

| Tripterygium wilfordii Hook. f. | - | - | T cells | Mice | STAT3 | IL-17, IL-22 | [62] |

| Vitis vinifera L. | Leaf | Water | THP-1; HEKa | Mice | AIM2 inflammasome | IL-17, IL-1β, IL-18, caspase-1, ASC | [104] |

| Withania somnifera | Seed | - | A431; THP-1; RAW264.7 | Mice | NF-κB | TNF-α, IL-6 | [48] |

aHK: adult human keratinocyte; AIM2: absent in melanoma 2; ASC: apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain; BAX: B cell lymphoma-2 associated X; Bcl-2: B cell lymphoma-2; CCL20: C-C motif chemokine ligand 20; CH2Cl2: dichloromethane; CSF1: colony-stimulating factor 1; EtOH: ethanol; HaCaT: human immortalized keratinocytes; HEKa: human epidermal keratinocytes, adult; HMEC-1: human dermal microvascular endothelial cell line; ICAM-1: intercellular adhesion molecule-1; iNOS: inducible nitric oxide synthase; JAK: Janus kinase; MCP-1: monocyte chemotactic protein 1; MeOH: methanol; MyD88: myeloid differentiation primary response 88; NF-κB: nuclear factor-kappa B; NLRP3: nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor protein 3; NO: nitric oxide; PCNA: proliferating cell nuclear antigen; PI3K: phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; STAT: signal transducer and activator of transcription; THP-1: Tohoku hospital pediatrics-1; TLR: toll-like receptor; -: not applicable

The effects of natural compounds on psoriasis

| Compound | Plant | In vitro | In vivo | Signaling pathway(s) | Target(s) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9,19-cycloartenol glycosides G3 | Cimicifuga simplex | PBMCs | Mice | JAK/STAT; Th17 cell differentiation | IL-17, IL-10, IFN-γ, IL-4 | [73] |

| Aloe polysaccharide | Aloe vera | HaCaT | - | NF-κB | TNF-α, IL-12, IL-8 | [51] |

| Andrographolide | Andrographis paniculata | BMDCs | Mice | TLR/MyD88 | IL-23, IL-1β, IL-6 | [106] |

| Ar-turmerone | Curcuma longa | HaCaT | - | Hedgehog | TNF-α, IL-8, IL-6, IL-1β | [107] |

| Baicalin | Scutellaria baicalensis | - | Mice | Th17 cell differentiation | IL-17, IL-22, IL-23, TNF-α | [33] |

| Betulinic acid | - | T cells | Mice | Th17 cell differentiation | IL-17, IL-10, IFN-γ | [34] |

| Chebulanin | Terminalia chebula Retz. | HaCaT | Mice | NF-κB | IL-17, IL-23, TNF-α, MMP-9 | [53] |

| Chrysin | - | NHEK | Mice | MAPK; JAK/STAT | IL-17, IL-22, TNF-α, CCL20 | [91] |

| cis-Khellactone | - | RAW264.7 | Mice | NF-κB; Th17 cell differentiation | IL-17, IL-23, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 | [50] |

| Cryptotanshinone | Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge. | HaCaT | Mice | STAT3 | PCNA | [63] |

| Curcumin | Curcuma longa | HaCaT | - | NF-κB | IL-6, IL-8 | [94] |

| PBMCs | Th17 cell differentiation | IL-17, IFN-γ | [96] | |||

| T cells | Mice | Th17 cell differentiation | IL-17, IL-22, IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-8, TNF-α | [95] | ||

| Fisetin | - | Human keratinocytes | - | PI3K/Akt/mTOR; MAPK | IL-17, IFN-γ | [108] |

| Gambogic acid | Garcinia harburyi | HaCaT; HUVEC | Mice | NF-κB; VEGF | ICAM-1, IL-17, IL-22, VEGFR2 | [97] |

| Glucosides | Paeonia lactiflora Pall | - | Mice | STAT1/3; Th17 cell differentiation | IL-17, IL-22, IL-23, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-12, IL-6, IFN-γ, PCNA | [75] |

| Glycyrrhizin | Glycyrrhiza glabra | HaCaT | Mice | NF-κB; MAPK | ICAM-1 | [92] |

| Honokiol | Magnolia officinalis | HUVEC; splenocytes | Mice | NF-κB; VEGF | TNF-α, IFN-γ, VEGFR2 | [98] |

| Imperatorin | Angelica hirsutiflora | Neutrophils; bEnd.3 | Mice | Akt; MAPK | Ki67, MPO, Ly6G | [109] |

| Indigodole D | Strobilanthes cusia | T cells | - | Th17 cell differentiation | IL-17 | [35] |

| Isogarcinol | Garcinia mangostana L. | HaCaT | Mice | Th17 cell differentiation | IL-17, IL-22, IL-23, TNF-α, IL-2, IFN-γ | [36] |

| Luteolin | - | HaCaT; NHEK | - | NF-κB | IL-6, IL-8, VEGF | [52] |

| Marumoside ANiazirinSitosterol-3-O-β-d-glucoside | Moringa oleifera L. | THP-1 | Mice | Th17 cell differentiation | IL-12, IL-17, IL-22, IL-23 | [38] |

| Paeoniflorin | Paeonia lactiflora Pall | HaCaT | Mice | NF-κB | IL-17, IL-22, IL-23, TNF-α | [49] |

| Saikosaponin A | Bupleurum Chinense | HEKa | Mice | NF-κB; NLRP3 | TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 | [99] |

| Shikonin | Leptospermum erythrorhizon | HaCaT | Mice | JAK/STAT3 | Caspase-3, cyclin E | [65] |

| - | Cyclin D1, p21, p53 | [64] | ||||

| Tussilagonone | Tussilago farfara | HaCaT | Mice | NF-κB; STAT3; Nrf2 | IL-6, IL-23, TNF-α, S100A7, CXCL8 | [93] |

| Vanillin | Vanilla planifolia | - | Mice | Th17 cell differentiation | IL-17, IL-23 | [37] |

| Withasteroid B | Datura metel L. | PBMCs | Mice | JAK/STAT3; Th17 cell differentiation | IL-17, IL-10 | [74] |

BMDCs: bone-marrow derived dendritic cells; CXCL8: chemokine ligand 8; HUVEC: human umbilical vein endothelial cell; MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase; MMP-9: matrix metalloproteinase-9; MPO: myeloperoxidase; mTOR: mammalian target of rapamycin; NHEK: normal human epidermal keratinocyte; Nrf2: nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2; PBMCs: peripheral blood mononuclear cells; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; VEGFR2: vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2; -: not applicable

The effects of herbal formulas on psoriasis

| Formula | Composition Plant | Extract method | In vitro | In vivo | Signaling pathway(s) | Target(s) | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant | Used part | |||||||

| Bai Xuan Xia Ta Re Pian | Euphorbiae humifusae L. | Aerial part | - | - | Mice | Th17 cell differentiation | IL-17, IL-23 | [40] |

| Terminalia chebula Retz. | Young fruitRipe fruit | |||||||

| Terminalia bellirica Roxb. | Fruit | |||||||

| Aloe vera | Leaf | |||||||

| Convolvulus scammonia | Resin | |||||||

| Dang Gui Liu Huang Tang | Angelica acutiloba Kitag. | Root | EtOH | HaCaT | Mice | MAPK; STAT3 | IL-22, CXCL10, K16, K17, Ki67 | [76] |

| Rehmannia glutinosa Libosch. | ||||||||

| Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi. | ||||||||

| Astragalus membranaceus Bunge. | ||||||||

| Coptis chinensis Franch. | ||||||||

| Phellodendron amurense Rupr. | Peel | |||||||

| Gold lotion | Citrus sinensis | Peel | EtOH | DCs | Mice | Th17 cell differentiation | IL-17, IL-22 | [39] |

| Citrus hassaku | ||||||||

| Citrus limon | ||||||||

| Citrus natsudaidai | ||||||||

| Citrus miyauchi Iyo | ||||||||

| Citrus unshiu | ||||||||

| PAMs | Carthamus tinctorius | - | EtOH | HaCaT | Mice | NF-κB | IL-8, TNF-α, ICAM-1, IL-23 | [54] |

| Lithospermum erythrorhizon | ||||||||

| Solanum indicum | ||||||||

| Cymbopogon distans | ||||||||

| PSORI-CM01 | Curcuma zedoaria | Rhizome | - | HaCaT | Mice | NF-κB; Th17 cell differentiation | IL-6, IL-8, CXCL10, CCL20 | [100] |

| Sarcandra glabra | Aerial part | |||||||

| Smilax glabra Roxb. | Rhizome | |||||||

| Prunus mume | Fruit | |||||||

| Arnebia euchroma (Royle) Johnst. | Root | |||||||

| Paeonia lactiflora | ||||||||

| Glycyrrhiza uralensis | ||||||||

| PSORI-CM02 | Smilax glabra Roxb. | Rhizome | Water | HaCaT | Mice | PI3K/Akt/mTOR | Beclin1, Atg 7, Atg 16L1, Atg 3 | [78] |

| Sarcandra glabra (Thunb.) Nakai | Leaf | |||||||

| Paeonia lactiflora Pall | Root | RAW264.7 | STAT1; STAT6 | TNF-α, iNOS, IL-1β | [77] | |||

| Curcuma phaeocaulis Val. | ||||||||

| Prunus mume Sieb. et Zucc. | Fruit | |||||||

| Psoriasis 1 | Smilacis glabrae | Rhizome | - | HaCaT | Rat | NF-κB; STAT | TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-22, IL-17, IL-1β, IL-4 | [102] |

| Folium isatidis | Leaf | |||||||

| Isatis tinctoria L. | Root | |||||||

| Angelica sinensis | ||||||||

| Hedyotis diffusa | Aerial part | |||||||

| Ligusticum striatum | Rhizome | |||||||

| Plantago major | Leaf | PBMCs | - | STAT4 | IL-17, IL-23, TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-6, IL-4, TGF-β | [101] | ||

| Kochia scoparia | Fruit | |||||||

| Lobelia chinensis | Aerial part | |||||||

| Alisma orientale | Rhizome | |||||||

| Dictamnus dasycarpus Turcz. | Cortex | |||||||

| Glycyrrhiza uralensis | Root | |||||||

Atg7: autophagy related 7; PAMs: plant antimicrobial solutions; TGF-β: transforming growth factor-beta; -: not applicable

Classical signaling pathways

Th17 cell differentiation pathway

Psoriasis has been considered an immune-mediated skin disease. Emerging evidence suggested the crucial role of Th17 cells in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. TGF-β in combination with proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-23, IL-6, and IL-1β, can drive the differentiation of naive T cells to Th17 cells. IL-23 further promotes the survival and proliferation of Th17 cells, as well as the migration of these cells into psoriatic skin lesions [23]. Th17 cells are considered a distinct subset of CD4+ Th cells by the ability to secrete IL-17, however, Th17 cells can also produce various inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-22, IL-21, IL-6, and TNF-α to promote inflammation and keratinocyte proliferation in psoriatic skin lesions [24]. Previous studies demonstrated that the serum levels of TGF-β, IL-17, IL-22, and IL-6 were significantly higher in patients with psoriasis compared with healthy subjects [25, 26].

Water-processed rosin from Pinus massoniana significantly reduced the proportion of Th17 cells in the spleen and inhibited the expression of Th17-related cytokines, including IL-17, IL-22, IL-23, and TNF-α in imiquimod (IMQ)-induced psoriasis-like mouse model [27]. Lavandula angustifolia essential oil and its component linalool showed significant decreases in IL-17 and IL-22 levels in IMQ-induced skin lesions [28]. Treatment with an ethanolic extract of Solanum xanthocarpum stem inhibited the skin expression of IL-17, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in the psoriasis mouse model [29]. Antrodia cinnamomea extract exerted inhibitory effects on Th17 cell differentiation and the production of IL-17, IL-22, and TNF-α in IMQ-treated mice [30]. Indigo naturalis, an extract from leaves of Baphicacanthus cusia (Ness) Bremek significantly decreased the expression of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-23 in keratinocytes, as well as inhibited the production of IL-17 and IL-22 in Jurkat T cells [31]. A methanolic extract of Euphorbia kansui root alleviated psoriasis symptoms by inhibiting the production of IL-23, IL-17, and IL-22 in lymph nodes from psoriatic mice [32].

Baicalin, the major flavonoid from Scutellaria baicalensis, inhibited IL-17 production in lymph nodes and decreased the expression of IL-23, TNF-α, IL-17, and IL-22 in skin lesions of IMQ-induced psoriatic mice [33]. Betulinic acid, a natural terpenoid, showed significant downregulation in the frequency of Th17 cells as well as the production of IL-17, TNF-α, and IL-6 in IMQ-treated mice [34]. Indigodole D extracted from Strobilanthes cusia suppressed IL-17 production in Th17 cells without any cytotoxicity [35]. Isogarcinol, a natural compound derived from Garcinia mangostana L. significantly inhibited Th17 cell differentiation and the expression of Th17-related cytokines, including IL-23, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-17, and IL-22 in a mouse model of psoriasis [36]. Vanillin, a phenolic aldehyde from Vanilla planifolia, suppressed the levels of IL-23 and IL-17 in psoriatic skin lesions [37]. Niazirin, sitosterol-3-O-β-d-glucoside, and marumoside A, three components of Moringa oleifera L., inhibited the production of IL-17, IL-22, and IL-23 in vitro, and reduced IL-17 messenger RNA (mRNA) level in vivo [38].

Gold lotion, an ethanolic extract of a mixture from peels of six citrus fruits, including Citrus sinensis (navel oranges), Citrus hassaku, Citrus limon, Citrus natsudaidai, Citrus miyauchi Iyo, and Citrus unshiu (Satsuma) decreased the ratio of Th17 cells in the spleen and reduced the expression of IL-23, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-17, and IL-22 at mRNA levels in skin lesions in IMQ-induced mouse model of psoriasis [39]. Bai Xuan Xia Ta Re Pian, a traditional herbal formula consisting of six herbs (Euphorbia Humifusae Herba, Chebula Fructus, Terminalia bellirica Fructus, Chebula Fructus Immaturus, Aloe, and Resina Scammoniae) significantly suppressed the expression of IL-23 and IL-17 in the skin of psoriatic mice [40].

NF-κB signaling pathway

NF-κB is a key transcription factor involved in the regulation of various cellular biological processes, including inflammatory responses [41]. Clinical studies in adult patients with moderate to severe psoriasis indicated that the level of the active form of NF-κB was significantly upregulated in psoriatic plaques, compared with non-lesional psoriatic skin and normal skin [42]. NF-κB transcription factor is a homodimer or heterodimer of NF-κB subunits (NFKBs), including p65 (RELA), RELB, p50, p52, and c-REL. In the baseline state, NF-κB dimers form a complex with the inhibitor of NF-κB (IκB) in the cytosol. Upon stimuli such as TNF-α, IκB kinase (IKK) phosphorylates IκB, leading to proteasomal degradation of IκB and releasing of NF-κB from the complex. Free NF-κB dimers translocate from the cytosol into the nucleus and bind to the promoter regions to regulate the transcription of various target genes [43]. NF-κB transcription factor is involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis by regulating the expression of numerous cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules to modulate inflammation, as well as keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation [42].

An ethanolic extract from leaves of Gynura pseudochina (L.) showed anti-psoriatic properties by inhibiting the translocation of NFKB RELB and suppressing the expression of IL-8 in TNF-α-stimulated HaCaT cells [44]. In vitro study suggested anti-psoriatic effect of three Thai medicinal herbs, including Alpinia galanga, Curcuma longa, and Annona squamosa by reducing the expression of NF-κB signaling-related genes, such as NF-κB1 (p50), NF-κB2 (p52), and RELA in HaCaT cells [45]. Oleoresin from Copaifera langsdorffii Desf. inhibited NF-κB nuclear translocation and decreased the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated THP-1 monocytes, suggesting its potential in psoriasis treatment [46]. Picea mariana extract decreased the expression of inflammatory molecules IL-6, IL-8, VEGF, and ICAM-1 by promoting phosphorylation and degradation of IκB, as well as suppressing phosphorylation of NF-κB in TNF-α-treated human keratinocytes [47]. Withania somnifera Dunal seed extract inhibited skin inflammation in 12-O-tetradecanoyl phorbol-13-acetate (TPA)-induced psoriasis in mice, reduced the expression of NF-κB and decreased the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α in LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells [48].

Paeoniflorin, the major bioactive compound from Paeonia lactiflora Pall, alleviated psoriasis-like skin symptoms in IMQ-induced mice and inhibited hyperproliferation by suppressing phosphorylation of IκB-α and NF-κB in psoriatic keratinocytes [49]. cis-Khellactone, a common pyranocoumarin, reduced IMQ-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation and decreased LPS-induced production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in macrophages by inhibiting phosphorylation of IKKα/β and NF-κB p65 [50]. Aloe polysaccharide, the main constituent of Aloe vera, decreased TNF-α-induced inflammation and proliferation in HaCaT cells by inhibiting phosphorylation of p65 and increasing the expression of IκB-α [51]. Luteolin, a common flavone, showed inhibitory effects on TNF-α-induced production of IL-6, IL-8, and VEGF, as well as hyperproliferation in HaCaT cells and NHEKs by decreasing mRNA levels of two genes (NFKB1 and RELA) and inhibiting nuclear translocation of NF-κB [52]. Chebulanin, a natural polyphenol derived from Terminalia chebula Retz., ameliorated IMQ-induced psoriatic skin lesions in mice and reduced inflammation and proliferation in HaCaT cells by decreasing phosphorylation of p65 at both mRNA and protein levels [53].

PAMs, a mixture of ethanolic extracts from Carthamus tinctorius, Lithospermum erythrorhizon, Solanum indicum, and Cymbopogon distans reduced skin symptoms in a psoriatic mouse model and inhibited the production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in HaCaT cells by suppressing nuclear translocation of NF-κB [54].

JAK/STAT signaling pathway

JAK/STAT pathway plays an important role in immune diseases by mediating various cytokine signalings to regulate inflammation and cell proliferation. JAK protein family includes four tyrosine kinases (TYKs): JAK1–3 and TYK2. The STAT family consists of seven members: STAT1–4, STAT5A, STAT5B, and STAT6. Upon binding of type I and II cytokines to their corresponding receptors, JAKs are activated and phosphorylated, leading to the recruitment and phosphorylation of STATs. Phosphorylated STATs can form dimers and translocate to the nucleus to regulate the transcription of various target genes involved in immune responses [55, 56]. Upregulated expression of JAK1 and STAT3 has been reported in skin lesions from patients with psoriasis, compared with normal skin. In addition, STAT3 expression had a positive correlation with the severity of psoriasis [57]. A variety of inflammatory cytokines related to psoriasis, such as IL-6, IL-23 can activate JAK/STAT signaling pathway to promote the development of psoriasis by triggering inflammatory response as well as keratinocyte proliferation in skin lesions [58]. Inhibition of JAK/STAT pathway by JAK inhibitors such as tofacitinib improved disease severity in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis [59], suggesting that modulation of JAK/STAT signaling pathway might a potential approach for psoriasis treatment.

An ethanolic extract of Illicium verum Hook. f. exhibited therapeutic potential for psoriasis by suppressing IFN-γ-induced ICAM-1 production in HaCaT cells via inhibiting JAK/STAT signaling pathway and decreasing the adhesion between T cells and keratinocytes [60]. Rehmannia glutinosa root extract alleviated epidermal thickening and skin levels of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-17, IL-23, TNFα) in the IMQ-induced psoriasis mouse model by suppressing phosphorylation of JAK1, JAK2, STAT1, and STAT3 [61]. Multi-glycoside of Tripterygium wilfordii Hook. f. inhibited the expression of IL-17 and IL-22 in psoriasis mice by suppressing STAT3 signaling pathway [62]. Cryptotanshinone, a bioactive compound from Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge. ameliorated psoriasis-like symptoms in IMQ-treated mice and reduced keratinocyte hyperproliferation by inhibiting STAT3 signaling pathway [63]. Shikonin, a main component of Leptospermum erythrorhizon improved skin severity in psoriasis mice and inhibited proliferation, promoted apoptosis, and decreased VEGF production in IL-17-stimulated HaCaT cells by suppressing activation of JAK/STAT3 signaling [64, 65].

Multiple signaling pathways

JAK/STAT and related signaling pathways

Studies indicated the involvement of JAK/STAT, particularly STAT3 signaling pathway in Th17 differentiation from naive T cells, leading to the production of various inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-17, IL-21, and IL-22 [66, 67]. Hyperactivation of STAT3 signaling triggered Th17 differentiation, while STAT3-deficiency resulted in impairment of Th17 differentiation in T cells [67]. Tofacitinib, an inhibitor of JAK/STAT pathway significantly inhibited the production of Th17 cytokines (IL-17, IL-22) [68]. In turn, IL-22 binds to its receptor and activates several downstream pathways, including JAK/STAT3, MAPK, and PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathways [69–71]. Other cytokines involved in Th17 differentiation, such as IL-6 and IL-23 also contributed to JAK/STAT activation [58].

A methanolic extract of root bark of Dictamnus dasycarpus Turcz. improved scaly skin lesions, reduced the number of inflammatory cell infiltration, and decreased epidermal thickness in IMQ-induced psoriasis mice by inhibiting STAT3 signaling pathway and reducing the number of Th17 cells as well as IL-17 production [72]. 9,19-cycloartenol glycosides G3, the main component of Cimicifuga simplex exhibited anti-psoriatic effects by suppressing the differentiation of CD4+ T cell into Th17 phenotype and inhibiting IFN-γ-induced JAK/STAT activation [73]. Withasteroid B isolated from Datura metel L. showed the inhibitory effects on JAK/STAT signaling pathway and reduced the ratio of Th17 cells as well as the production of Th17-related inflammatory cytokines [74]. Total glucosides extracted from Paeonia lactiflora Pall alleviated IMQ-induced psoriasis-like skin symptoms in mice, inhibited Th17 differentiation, and suppressed phosphorylation of STAT1 and STAT3 [75].

Dang Gui Liu Huang Tang, a traditional herbal formula consisting of Angelica acutiloba Kitag., Rehmannia glutinosa Libosch., Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi., Astragalus membranaceus Bunge., Coptis chinensis Franch., and Phellodendron amurense Rupr., improved psoriasis symptoms in IMQ-induced mice and reduced the production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, as well as suppressed hyperproliferation in human keratinocytes by inhibiting the activation of STAT3 and MAPK signaling pathways [76]. PSORI-CM02, a traditional formula including five herbs, Smilax glabra Roxb., Sarcandra glabra (Thunb.) Nakai, Paeonia lactiflora Pall, Curcuma phaeocaulis Val., and Prunus mume Sieb. et Zucc., showed anti-psoriatic effects by suppressing STAT1/6 and PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathways in keratinocytes and immune cells [77, 78].

NF-κB and related signaling pathways

NF-κB pathway can be activated by several upstream pathways, including PI3K/Akt and MAPK signalings to regulate inflammation [79, 80]. Nrf2 signaling can attenuate NF-κB activation, and in contrast, NF-κB could suppress Nrf2 activity [81]. NF-κB and JAK/STAT signaling pathways are involved in the regulation of inflammatory response in psoriasis. A previous study demonstrated that JAK/STAT signaling synergized with NF-κB to activate the transcription of various inflammatory genes in response to stimuli [82]. NF-κB activation also modulates many downstream signaling pathways which are involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. NF-κB signaling shows intrinsic and extrinsic effects on Th17 differentiation [83]. VEGF signaling, which is important in regulating angiogenesis (a hallmark of psoriasis), is also a downstream pathway of NF-κB [84]. Moreover, NF-κB pathway was suggested to be involved in NLRP3 inflammasome activation in psoriasis [85].

Astragalus sinicus L. extract suppressed the production of inflammatory molecules in TNF-α/IFN-γ-stimulated human keratinocytes and IL-23-induced psoriasis-like mouse model by inhibiting NF-κB, STAT1/3, and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways [86]. An aqueous extract of Actinidia arguta shows inhibitory effects on IMQ-induced cutaneous inflammation and cytokine-induced inflammation and hyperproliferation in HaCaT cells by suppressing phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 and STAT1/3 [87]. Extracts from Sinapis Alba Linn and Datura metel L. exerted anti-psoriatic effect by inhibiting NF-κB and NLRP3 inflammasome signaling pathways [88–90].

Chrysin, a common flavone found in various natural sources, such as honey, passion flowers, or propolis, alleviated IMQ-induced psoriasis symptoms in mice and inhibited the production of inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and antimicrobial peptides in keratinocytes by suppressing NF-κB, MAPK, and JAK/STAT signaling pathways [91]. Glycyrrhizin, a major component of Glycyrrhiza glabra, improved psoriasis-like skin lesions in IMQ-induced mice and reduced ICAM-1 production in TNF-α-stimulated HaCaT cells by inhibiting NF-κB/MAPK signaling [92]. Tussilagonone, a natural compound derived from Tussilago farfara, alleviated psoriasis symptoms in IMQ-treated mice and TNF-α-treated keratinocytes via Nrf2 activation and NF-κB/STAT3 inhibition [93]. Curcumin, a main compound of Curcuma longa, attenuated psoriasis pathology by inhibiting and NF-κB and Th17 differentiation pathways in keratinocytes and immune cells [94–96]. Honokiol (a lignan isolated from Magnolia officinalis) and gambogic acid (a xanthone from Garcinia harburyi) showed the anti-psoriatic effect by suppressing NF-κB/VEGF signaling pathway [97, 98]. Saikosaponin A, a component of Bupleurum chinense, reduced psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) scores and epidermal hyperplasia in IMQ-induced mice and attenuated cytokine-induced inflammation in human keratinocytes by suppressing the phosphorylation of NF-κB and the expression of NLRP3 [99].

PSORI-CM01, a herbal formula consisting of seven plants Curcuma zedoaria, Sarcandra glabra, Smilax glabra Roxb., Prunus mume, Arnebia euchroma (Royle) Johnst., Paeonia lactiflora, and Glycyrrhiza uralensis, exerted the anti-psoriatic effect by suppressing the translocation of NF-κB p65 and inhibiting Th17 differentiation signaling [100]. Psoriasis 1, a mixture of 12 herbs including Smilacis glabrae, Folium isatidis, Isatis tinctoria L., Angelica sinensis, Hedyotis diffusa, Ligusticum striatum, Plantago major, Kochia scoparia, Lobelia chinensis, Alisma orientale, Dictamnus dasycarpus Turcz., and Glycyrrhiza uralensis, alleviated psoriasis inflammation by inhibiting the phosphorylation of IKK, NF-κB p65, STAT3, and STAT4 in keratinocytes and T cells [101, 102].

Other signaling pathways

An ethanolic extract of Artemisia capillaris ameliorated IMQ-induced psoriasis-like symptoms in mice and showed antiproliferative effect by promoting apoptosis in keratinocytes [103]. The leaf extract of Vitis vinifera L. alleviated psoriatic inflammation by inhibiting the activation of AIM2 inflammasome signaling [104]. Salvia miltiorrhiza extract [also known as danshensu in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM)] suppressed epidermal hyperplasia in IMQ-induced mice and hyperproliferation in cytokine-stimulated keratinocytes by reducing the expression of yes-associated protein (YAP, an important component of Hippo signaling pathway) [105]. Andrographolide, a major component from Andrographis paniculata, exerted the anti-psoriatic effect by inhibiting TLR/MyD88 signaling in DCs [106]. Ar-turmerone, a sesquiterpenoid from Curcuma longa, suppressed TNF-α-induced inflammation and proliferation in HaCaT cells by inhibiting Hedgehog signaling pathway [107]. Fisetin (a common flavonol) and imperatorin (a furocoumarin derived from Angelica hirsutiflora) alleviated psoriasis-like symptoms by suppressing PI3K/Akt/mTOR and MAPK signaling pathways in keratinocytes and immune cells, respectively [108, 109].

Clinical efficacy of natural products in psoriasis treatment

Clinical studies demonstrated the anti-psoriatic effects of natural products are shown in Table 4. Topical application of extract from sea buckthorn, Indigo naturalis, Hypericum perforatum, and Gynura pseudochina showed significant reductions in skin severity compared with placebo in patients with mild to moderate psoriasis [110–113]. Sea buckthorn has been traditionally used for thousands of years for treatment of skin diseases due to its anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects [114]. Indigo naturalis has been widely used for psoriasis treatment in TCM for over 50 years [115]. Hypericum perforatum and Gynura pseudochina are also common medicinal plants used to treat skin symptoms [116, 117]. Herbal formula Pulian ointment (consisting of two herbs: Phellodendron amurense and Scutellaria baicalensis) and Shi Du Ruan Gao (a mixture of six herbs: Indigo naturalis, Cortex Phellodendri, Gypsum fibrosum preparatum, Calamine, Galla chinensis) also exerted anti-psoriatic activity by decreasing PASI scores without any severe adverse events after four weeks and eight weeks of topical treatment, respectively [118, 119]. Pulian ointment has been approved by Beijing Food and Drug Administration as a prescription use in hospitals in China for treatment of psoriasis [119]. Shi Du Ruan Gao has been developed and used for psoriasis treatment in hospital for over 60 years [118].

Clinical efficacy of natural products

| Herb/formula | Type of study | Patients | Treatment | Efficacy outcome | Adverse effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gynura pseudochina var. hispida Thv. | Randomized, positive-controlled | n = 25Mild to moderate chronic plaque psoriasis | Topical 4 weeks | Significant decrease in scaling scores, epidermal thickness, NF-κB p65, and Ki-67 expression | No laboratory abnormalities | [113] |

| Indigo naturalis | Randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled | n = 24 Moderate psoriasis | Topical 8 weeks | Significant reduction in PASI scores compared with placebo | Not evaluated | [112] |

| Liang xue huo xue (Radix Rehmanniae, Sophora flower, Salvia miltiorrhiza, Rhizoma Imperatae, puccoon, red peony, Caulis Spatholobi) | Multi-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | n = 50Blood heat syndrome psoriasis | Oral 6 weeks | Significant reduction in PASI scores and serum IL-17 level compared with placebo | No abnormal vital signs | [120] |

| Liangxue Jiedu (Rhizoma Smilacis Chinae, Flos Sophorae, Radix Lithospermi, Rhizoma Paridis, Radix Rehmanniae, Cortex Dictamni Radicis, Radix Paeoniae Rubra, Flos Lonicerae, Rhizoma Imperatae, Radix Sophorae Flavescentis) | Multicenter, randomized, controlled | n = 247Blood heat type psoriasis | Oral 8 weeks | Significant improvement in skin lesions and symptoms compared with Western medicine treatment | No significant abnormalities | [124] |

| Pulian (Phellodendron amurense, Scutellaria baicalensis) | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | n = 300Blood heat syndrome psoriasis | Topical 4 weeks | Significant reduction in PASI scores compared with placebo | No adverse event | [119] |

| Sea buckthorn | Single-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized | n = 10PASI score: 1–12 | Topical 4 weeks | Significant improvement in PASI scores and DLQI scores compared with placebo | Not evaluated | [110] |

| Shi Du Ruan Gao (Indigo naturalis, Cortex Phellodendri, Gypsum fibrosum preparatum, Calamine, Galla chinensis) | Single-center, randomized, investigator-blinded, parallel group, placebo-controlled | n = 100Mild to moderate chronic plaque psoriasis | Topical 8 weeks | Significant improvement in the TSS, IGA, and Global Subjects’ Assessment of treatment compared with placebo | No severe adverse events | [118] |

| St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum L.) | Single-blind, placebo-controlled | n = 10Symmetrical plaque-type psoriasis | Topical 4 weeks | Significant reduction in PASI scores compared with placebo | Not evaluated | [111] |

| Yinxieling (Radix Rehmanniae recen, Angelica sinensis, Radix Paeoniae Rubra, Ligusticum wallichii, Lithospermi radix, Curcuma zedoaria Chloranthus spicatus, Rhizoma Smilacis glabrae, smoked plum, liquorice) | Randomized controlled | n = 120 | Oral 8 weeks | Significant reduction in PASI scores and serum level of TNF-α and IL-8 compared with placebo | Not evaluated | [121] |

DLQI: dermatology life quality index; IGA: investigator global assessment; TSS: total severity score

Oral administration of herbal formula Liang xue huo xue decoction (seven herbs: Radix Rehmanniae, Sophora flower, Salvia miltiorrhiza, Rhizoma Imperatae, puccoon, red peony, Caulis Spatholobi) and Yinxieling (10 herbs: Radix Rehmanniae recen, Angelica sinensis, Radix Paeoniae Rubra, Ligusticum wallichii, Radices lithospermi, Curcuma zedoaria, Chloranthus spicatus, Rhizoma Smilacis glabrae, smoked plum, liquorice) significantly improved PASI scores and reduced serum levels of inflammatory cytokines in psoriasis patients, compared with placebo [120, 121]. Liang xue huo xue was used for psoriasis treatment due to its anti-proliferative effects on keratinocytes [122]. Yinxieling has been applied in clinical and exerted effectiveness in treatment of psoriasis [123]. Treatment with Liangxue Jiedu decoction (10 herbs: Rhizoma Smilacis Chinae, Flos Sophorae, Radix Lithospermi, Rhizoma Paridis, Radix Rehmanniae, Cortex Dictamni Radicis, Radix Paeoniae Rubra, Flos Lonicerae, Rhizoma Imperatae, Radix Sophorae Flavescentis) showed significant improvements in skin symptoms in comparison with Western medicine (cetirizine hydrochloride, vitamin C, and vitamin B complex) after eight weeks [124]. Liangxue Jiedu decoction was used for treatment of psoriasis in TCM due to its immunomodulatory activity [125].

All the nine clinical studies mentioned in Table 1 were randomized studies with single-blind or double-blind, single-center or multi-center, and placebo-controlled or positive-controlled observation. These studies were conducted in small groups of patients (10–50 patients) or larger groups (100–300 patients). Participants were included in clinical studies consisting of both men and women, aged from 18 years old to 80 years old with skin symptoms from mild to severe. Some studies specifically targeted the patients with the blood heat syndrome based on TCM diagnosis. According to TCM, blood heat is the most common syndrome (53.8%) in patients with psoriasis, compared with blood-dryness (27.4%) and blood-stasis syndrome (18.1%) [126]. Hence, the number of blood heat type psoriasis patients might be large enough for studies rather than other types. Moreover, blood heat type patients also exhibited typical features of psoriasis with elevated levels of Th1/Th17-related cytokines, IFN-γ, IL-17, IL-23, and TNF-α [127]. Duration of treatments ranged from four weeks to eight weeks for topical application and from six weeks to eight weeks for oral administration. Both oral and topical treatment showed therapeutic effects on psoriasis in comparison with placebo or positive control drugs with no significant adverse events.

Herbal products were also used in combination with other therapies in the treatment of psoriasis. Oral administration of Curcuma longa extract combined with ultraviolet A (UVA) therapy showed higher effects on skin severity compared with psoralen plus UVA [128]. Treatment with total glucosides of paeony, a bioactive component derived from dry paeony root in combination with acitretin significantly improved PASI50 (50% reduction of PASI scores) in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis, in comparison with placebo plus acitretin [129]. Oral treatment of a Korean herbal formula Yangdokbagho-tang (a mixture of six ingredients: Gypsum fibrosum, Rehmanniae Radix Crudus, Anemarrhenae Rhizoma, Schizonepetae Spica, Saposhnikoviae Radix, Arctii Semen) combined with acupuncture, probiotics, and phototherapy reduced PASI scores in two cases of moderate and severe psoriasis [130].

Several clinical trials also demonstrated that there were no significant differences between the effects of natural products and placebo or drug treatment on psoriasis symptoms. Application of ointment with silver fir (Abies alba) bark showed no significant effects compared with placebo [131]. The anti-psoriatic effects of Tripterygium wilfordii extract were not significantly different in comparison with acitretin [132]. Oral treatment with a TCM formula consisting of 16 herbs (Herba ephedrae, Radix aconiti lateralis preparate, Semen sinapis, Cortex cinnamomi, Rhizoma zingiberis, Cornu cervi degelatinatum, Radix rehmanniae preparate, Rhizoma Smilacis Glabrae, Cortex Dictamni, Rhizoma Imperatae, Radix salviae miltiorrhizae, Caulis spatholobi, Arnebiae Radix, Flos Sophorae, Radix glycyrrhizae, Indigo naturalis) for six months showed less effective outcomes compared with both placebo and methotrexate [133].

Discussion

Natural products have been used to treat psoriasis for centuries with significant effectiveness and few adverse events. In the aspect of TCM, psoriasis includes three phenotypes: blood heat in the active stage, blood dryness in the regression stage, and blood stasis in the resting stage. Blood heat phenotype is characterized by the continuous appearance of spot-like skin rash and skin itching. Blood dryness features include coin-like skin rash with light red color. The symptoms of blood stasis are thickened dark red skin lesions. Among these three phenotypes, blood heat is the most common with over 50% of patients suffering from this syndrome [126]. Several herbal formulas listed in Table 4 exerted efficacy on the treatment of blood heat type of psoriasis. Among the clinical trials listed in Table 4, studies investigating the clinical efficacy of Liangxue Jiedu and Pulian might be considered most valuable due to the large numbers of participants in these studies. However, since the scientific evidence for traditional herbal medicines or natural products is still limited, large-scale clinical trials (1,000 participants or more) to examine their efficacies have not been conducted. This review organized and summarized the underlying mechanisms for anti-psoriatic effects of natural products, which support the scientific base for future clinical trials.

Medicinal herbs and traditional herbal formulas consist of various active compounds with multiple targets and multiple related signaling pathways. This characteristic might lead to the higher effects of natural products but might be an obstacle to investigate their mechanisms of action for psoriasis treatment. Moreover, the chemical composition of a plant might vary in the number of compounds, as well as the amount of each compound under different growth environments, leading to the difficulty in the repetition of experiments. Therefore, clarification of the major component in the plants is important in the study of herbal medicines. In this review, we summarized the anti-psoriatic effects of natural products, including natural compounds, herb extracts, and herbal prescriptions. These natural products target numerous psoriasis-related signaling pathways, such as Th17 differentiation, JAK/STAT, NF-κB, MAPK, PI3K/Akt/mTOR, and other signaling pathways to alleviate inflammatory response and reducing keratinocyte hyperproliferation, thus improving psoriasis symptoms. Based on the current review, inhibiting Th17 differentiation pathway as well as related targets, such as IL-17, IL-22, IL-23, and TNF-α was the most common mechanism of action of natural products against psoriasis. These targets might be considered the most credible targets and might be applied in psoriasis studies using natural products.

Most animal studies utilized IMQ-induced mice as a model of psoriasis. Application of IMQ (a ligand of TLR7/8) to mouse skin can induce inflammatory skin lesions, resembling psoriasis symptoms in humans with activation of IL-23/IL-17 axis [134]. After the first report in 2009, IMQ-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation in mice was widely used to investigate new underlying mechanisms in the pathogenesis of psoriasis, as well as to examine the therapeutic effects of potential agents. However, this model has certain limitations. There are several critical differences between mouse and human skin, including permeability, thickness, cutaneous immunity, and renewal process of epidermis and hair follicles, leading to the differences in drug absorption and immune response in the mouse model, compared with the human [135]. Therefore, the use of other models, which more resemble human skin, such as human three-dimensional skin equivalents is necessary and appropriate to investigate the anti-psoriatic effect of natural products.

In conclusion, natural products show promising application in the treatment of psoriasis. The underlying mechanisms of action for the anti-psoriatic effect of natural compounds and herbal products are complex with the involvement of multiple signaling pathways (Figure 2). Further studies to evaluate the therapeutic effects of natural products in more relevant psoriasis models and larger-scale clinical trials should be conducted in the future.

The signaling pathways underlying anti-psoriatic effects of natural products. Act1: NF-κB activator 1; P: phosphorylated; RIP: ribosome inactivating protein: TAK1: transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase 1; TRADD: Tumor necrosis factor receptor type 1-associated death domain; TRAF6: tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6

Abbreviations

| AIM2: | absent in melanoma 2 |

| DCs: | dendritic cells |

| HaCaT: | human immortalized keratinocytes |

| ICAM-1: | intercellular adhesion molecule-1 |

| IFN: | interferon |

| IKK: | inhibitor of nuclear factor-kappa B kinase |

| IL: | interleukin |

| IMQ: | imiquimod |

| IκB: | inhibitor of nuclear factor-kappa B |

| JAK: | Janus kinase |

| LPS: | lipopolysaccharide |

| MAPK: | mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| mRNA: | messenger RNA |

| mTOR: | mammalian target of rapamycin |

| MyD88: | myeloid differentiation primary response 88 |

| NF-κB: | nuclear factor-kappa B |

| NFKBs: | nuclear factor-kappa B subunits |

| NHEK: | normal human epidermal keratinocyte |

| NLRP3: | nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor protein 3 |

| Nrf2: | nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| PAMs: | plant antimicrobial solutions |

| PASI: | psoriasis area and severity index |

| PI3K: | phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase |

| STAT: | signal transducer and activator of transcription |

| TCM: | traditional Chinese medicine |

| TGF-β: | transforming growth factor-beta |

| Th17: | T helper 17 |

| THP-1: | Tohoku hospital pediatrics-1 |

| TLR: | toll-like receptor |

| TNF: | tumor necrosis factor |

| VEGF: | vascular endothelial growth factor |

Declarations

Author contributions

The author contributed solely to the work.

Conflicts of interest

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2022.