Abstract

Neurological disorders including neurodegenerative disorders continue to pose significant therapeutic challenges. Triterpenoids, a diverse group of natural compounds found abundantly in plants, possess promising neuroprotective properties. This review aims to explore the potential of triterpenoids in mitigating neurodegeneration through various mechanisms, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic activities. The neuroprotective potential of some notable triterpenoids, such as asiatic acid, asiaticoside, madecassoside, bacoside A, bacopaside I, ganoderic acids, and lucidenic acids are discussed in terms of their ability to modulate key pathways implicated in neurological disorders. Additionally, the potential therapeutic applications of triterpenoids in Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, cerebral ischemia, spinal cord injury, and epilepsy are examined. Furthermore, the review also underlines the challenges for the development of triterpenoids as neuroprotective agents, including the need for further preclinical and clinical studies to elucidate their efficacy and safety for translation into clinical practice.

Keywords

Triterpenoids, neuroprotective, neuroprotection, asiatic acid, asiaticoside, madecassoside, bacosides, Ganoderma lucidumIntroduction

Neurological conditions like epilepsy, cerebral ischemia, and spinal cord injury (SCI), together with neurodegenerative disorders impose a substantial burden on global healthcare systems due to the lack of effective treatments. These disorders are mainly characterized by neuroinflammation, neuronal apoptosis, and neurodegeneration, ultimately leading to cognitive decline, motor impairment, and physical disability. Despite extensive research efforts, the underlying mechanisms driving neurodegeneration remain incompletely understood, hampering the development of successful therapeutic interventions.

Since ancient times, many natural products e.g., Gingko biloba, turmeric (Curcuma longa), Brahmi (Bacopa monnieri), ashwagandha (Withania somnifera), green tea (Camellia sinensis), ginseng, have been known for their neuroprotective properties, with terpenoids being one of the most noteworthy and extensively researched categories. Terpenoids have long been recognized for their neuroprotective properties owing to their diverse pharmacological actions and potential to modulate multiple pathways implicated in neuronal damage [1]. Terpenoids encompass a vast array of neuroactive compounds distributed across major subcategories such as monoterpenoids, diterpenoids, sesquiterpenoids, triterpenoids, and tetraterpenoids. While monoterpenoids [2], diterpenoids [3], and sesquiterpenoids [4] have been extensively reviewed for their neuroprotective potential, a comprehensive review on triterpenoids has not been undertaken in nearly a decade, to the best of our knowledge, even though it is renowned for harboring some of the most notable neuroprotective agents [5, 6]. Owing to the growing body of research elucidating the neuroprotective properties of triterpenoids, this review aims to provide a detailed overview of the neuroprotective prospects of some notable triterpenoids, focusing on their mechanisms of action, preclinical evidence, and potential therapeutic applications in various neurodegenerative diseases.

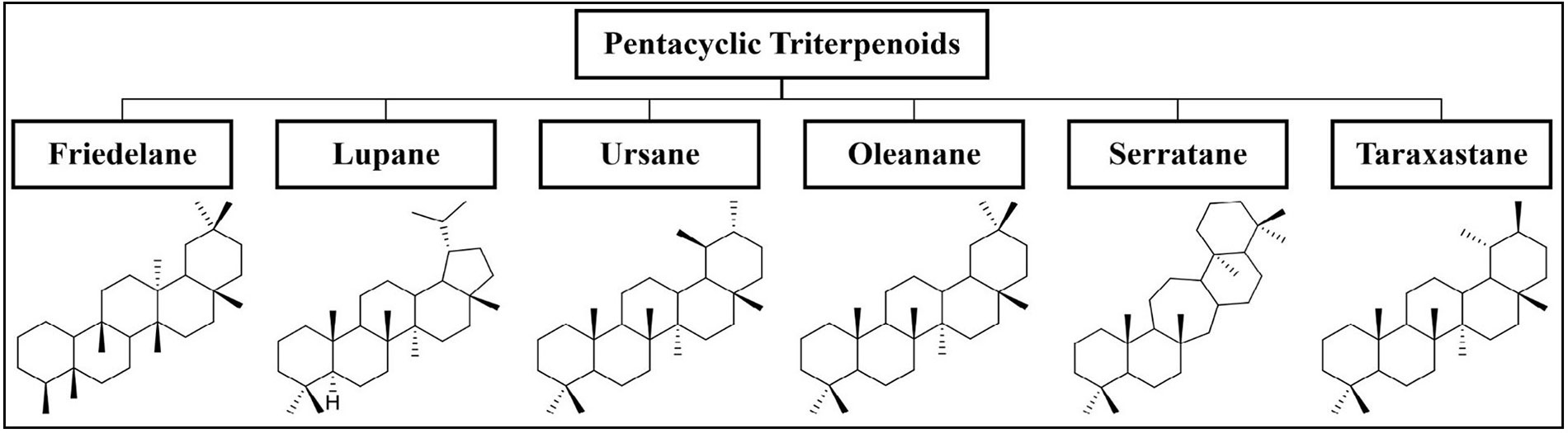

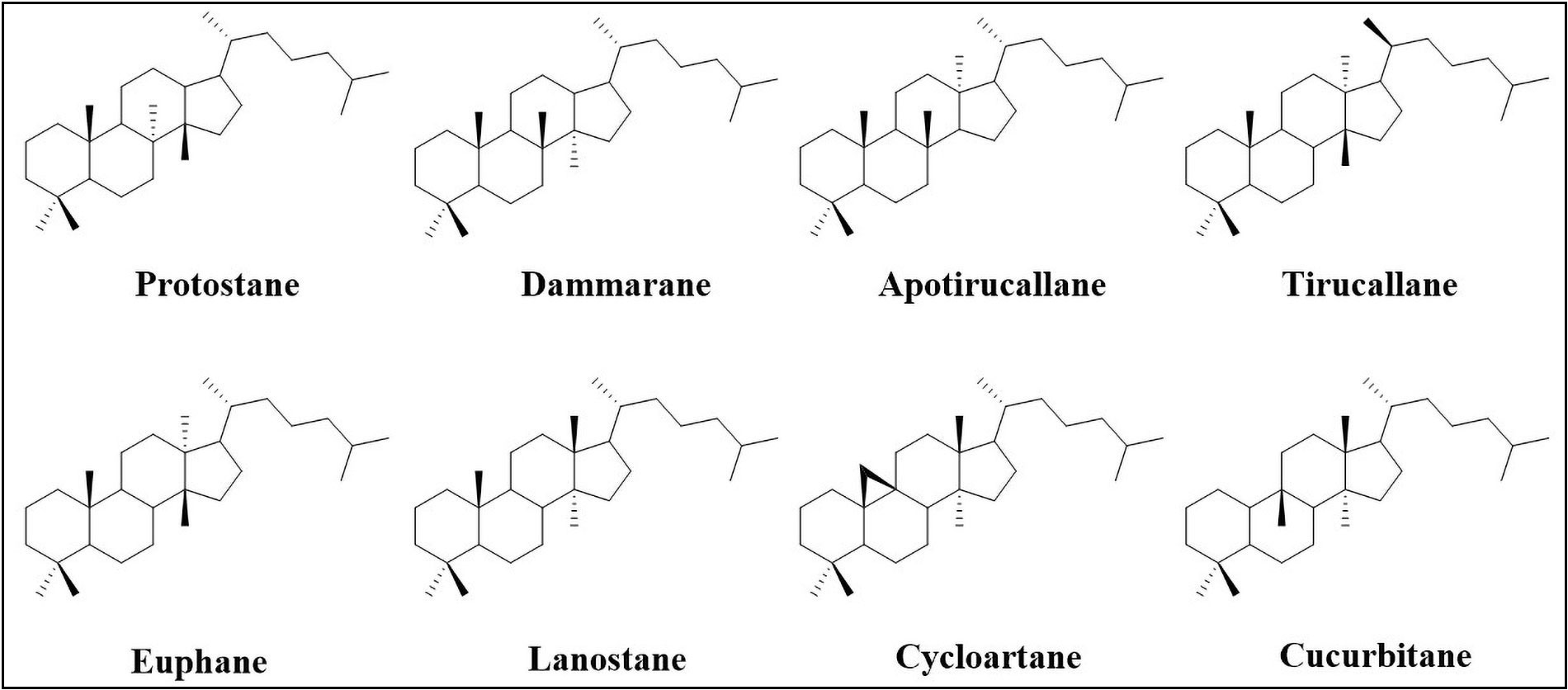

Triterpenoids are C30 terpene compounds having six isoprene units. According to their structure, triterpenoids can be divided into acyclic, mono-, bi-, tri-, tetra-, and pentacyclic triterpenoids. Among these, tetracyclic and pentacyclic triterpenoids constitute the major subcategories. Pentacyclic triterpenoids constitute the largest group of triterpenoids and are mainly sub-classified into six groups: friedelane, lupane, ursane, oleanane, serratane, and taraxastane (Figure 1). Tetracyclic triterpenoids can be classified into the following sub-groups i.e. protostane, dammarane, apotirucallane, tirucallane, euphane, lanostane, cycloartane, and cucurbitane (Figure 2) [7, 8]. Table 1 lists some of the notable triterpenoids with known neuroprotective activity.

Notable triterpenoids with their biological sources

| Triterpenoid class | Name | Biological sources |

|---|---|---|

| Pentacyclic triterpenoids | ||

| (a) Ursane type | Asiatic acid | Centella asiatica |

| Asiaticoside | Centella asiatica | |

| Madecassoside | Centella asiatica | |

| β-boswellic acid | Boswellia serrata | |

| Ursolic acid | Mirabilis jalapa, apple peals | |

| (b) Oleanane type | α-boswellic acid | Boswellia serrata |

| Glycyrrhizic acid | Glycyrrhiza glabra | |

| Maslinic acid | Olives | |

| (c) Lupane type | Betulin | Betula papyrifera |

| Betulinic acid | Betula papyrifera | |

| Lupeol | Camellia japonica, Mangifera indica, Acacia visco | |

| (d) Friedalane type | Celastrol | Tripterygium wilfordii |

| Tetracyclic triterpenoids | ||

| (a) Dammarane type | Bacoside A | Bacopa monnieri |

| Bacopaside I | Bacopa monnieri | |

| Ginsenosides | Panax ginseng | |

| (b) Lanostane type | Ganoderic acid A | Ganoderma lucidum |

| Lucidenic acids | Ganoderma lucidum | |

| (c) Cycloartane type | Astragaloside IV | Astragalus membranaceus |

| (d) Cucurbitane type | Cucurbitacin B | Cucurbitaceous plants |

The preclinical studies have demonstrated that the neuroprotective potential of triterpenoids stems from their ability to exert antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic activities, thereby counteracting key pathological processes underlying neurodegeneration. In light of these findings, there is a growing interest in exploring the therapeutic applications of triterpenoids. This review aims to provide a detailed overview of the neuroprotective prospects of some notable triterpenoids, focusing on their mechanisms of action, preclinical evidence, and potential therapeutic applications in the management of neurological disorders. During the survey of literature, a prevalent utilization of plant extracts in studies investigating the neuroprotective effects of triterpenoids was noted. To uphold the robustness of the data, studies exclusively featuring the investigation of the isolated, pure compound of interest were curated. With this approach, this review discusses the neuroprotective properties of asiatic acid, asiaticoside, madecassoside, bacoside A, bacopaside I, ganoderic acids, and lucidenic acids, so as to stimulate further research efforts aimed at harnessing the neurotherapeutic potential of triterpenoids.

Neuroprotective properties of triterpenoids

Asiatic acid

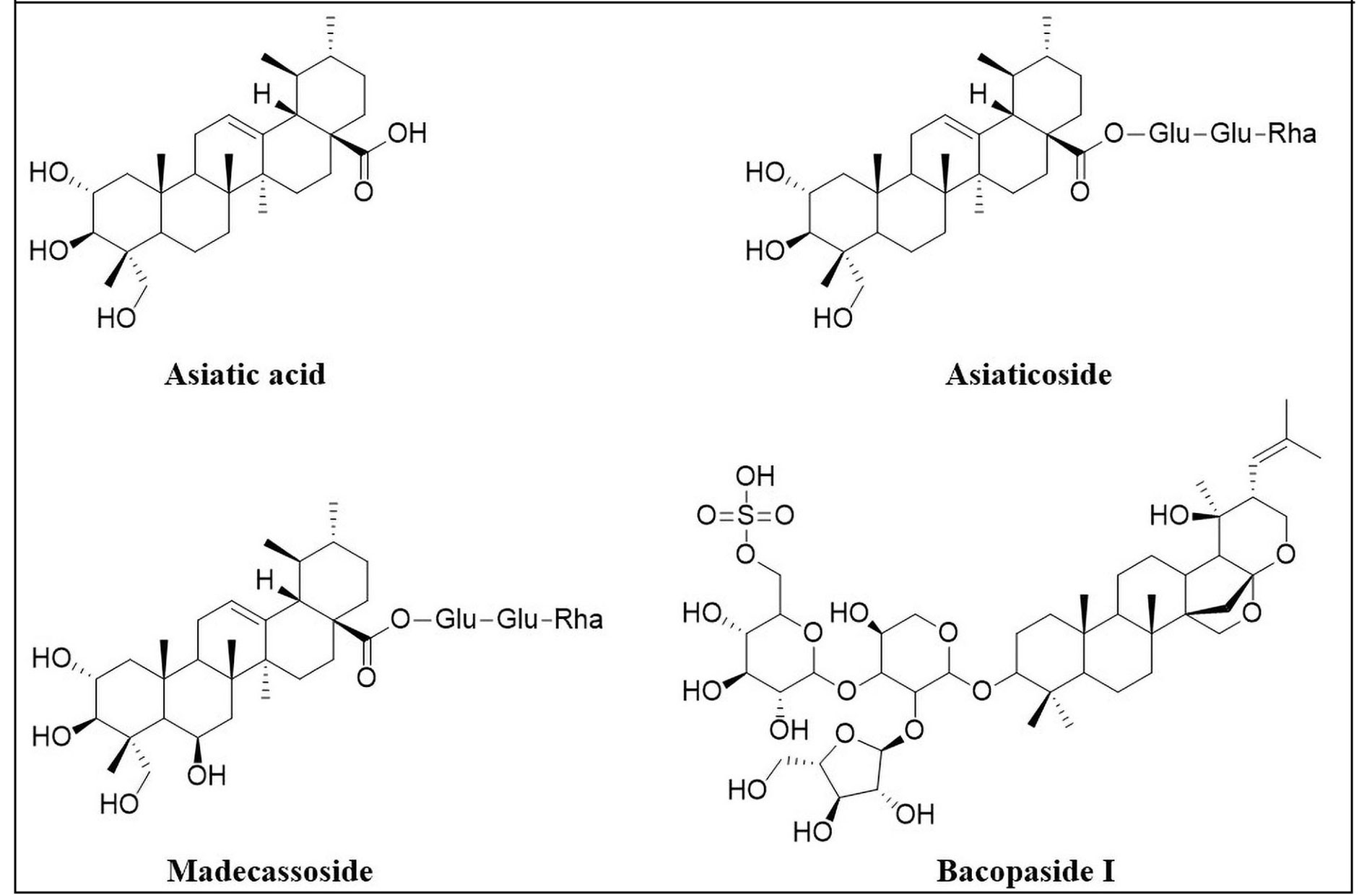

Asiatic acid (Figure 3), an ursane-type of pentacyclic triterpenoid, is one of the most prominent chemical constituents of Centella asiatica. Centella asiatica (Apiaceae), commonly known as “Mandukparni”, is a medicinal plant that has long been utilised in Ayurvedic medicine as a nerve tonic. It contains α-amyrin triterpenoids, including asiaticoside and madecassoside, which contribute to its neuroprotective properties. Asiatic acid, the aglycone component of asiaticoside is a potent neuroprotective agent, primarily due to its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, cognition-enhancing, and neurogenesis-enhancing properties [9–20]. Thus, it is being considered as a potential candidate for management of neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [16, 21–24] and Parkinson’s disease (PD) [25–28]. Furthermore, it has also shown potential benefits for epilepsy [29, 30], cerebral ischemia [31–34], SCI [35, 36], and traumatic brain injury [37].

Alzheimer’s disease

AD is a neurodegenerative disorder associated with progressive decline of memory and cognitive function. The pathogenesis of AD is a complex process linked to multiple factors, including the accumulation of β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques, formation of the neurofibrillary tangles, impaired cholinergic neurotransmission, astrogliosis, dystrophy of neurites and increased oxidative stress and neuroinflammation. Several studies have demonstrated that asiatic acid has the potential to improve AD pathology through diverse mechanisms, including inhibition of Tau hyperphosphorylation and apoptosis, as well as suppression of oxidative stress and neuroinflammation.

Research group led by Ahmad Rather et al. [24] have shown that asiatic acid can attenuate aluminium chloride (AlCl3)-induced neurodegeneration in rats [23]. Cognitive function was notably improved following co-administration of asiatic acid (75 mg/kg) for seven weeks by oral route. This was evident from the improved spatial memory and decreased anxiety in a number of behavioural tests including the open field test, elevated plus maze test, and radial arm maze tests. Asiatic acid also caused downregulation of the Tau-phosphorylation markers, namely cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (CDK5) and phosphorylated Tau (pTau), indicating its ability to suppress AlCl3-induced Tau hyperphosphorylation. In addition, the anti-apoptotic effect was observed on neurons, as shown by the downregulation of pro-apoptotic regulators namely, Bcl-2-associated X protein (Bax), caspase-3, 6, 8, and 9, as well as upregulation of anti-apoptotic protein, Bcl-2. Hence, it can be inferred that the enhancement in cognitive function may be due to suppression of Tau hyperphosphorylation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis. The activation of the AKT/glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta (GSK-3β) pathway, which plays a crucial role in promoting neuronal survival and protecting neurons from apoptosis, was suggested as the probable mechanism underlying these actions. This was indicated by markedly enhanced expression of pAKT and phosphorylated GSK-3β (pGSK-3β) in the hippocampus and cortex. Therefore, activation of this pathway by asiatic acid may have contributed to its observed anti-apoptotic effect. These observations are in line with the findings reported by Cheng et al. [21].

Additionally, Cheng et al. [21] also showed that asiatic acid can ameliorate Aβ-induced neurotoxicity in differentiated pheochromocytoma (PC12) cells, by preventing mitochondrial dysfunction, as one of its key mechanisms of action. Mitochondrial dysfunction, which leads to the release of cytochrome c in the cytosol and causes consequent initiation of apoptosis, was inhibited by pre-treatment with asiatic acid (20 μM). This was evidenced by reduction in the level of cytoplasmic cytochrome c, which was observed even at lower concentrations of 10 μM and 5 μM. Moreover, it restored the balance of apoptotic regulators, as shown by upregulation of the Bcl-2/Bax ratio as well as the downregulation of caspase-3, 9, and Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1). These findings were corroborated by Lou et al. [22] who demonstrating the protective effect of asiatic acid against C2-ceramide-induced apoptosis in rat cortical neuronal cells by inhibition of mitochondria-mediated apoptosis. As asiatic acid was found to increase the activity of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2), the authors hypothesized that it inhibited the ERK1/2 dephosphorylation by modulation of the ERK1/2 signaling pathway.

Parkinson’s disease

After AD, PD is the second most prevalent neurodegenerative disorder, which is characterized by progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta region in the midbrain. Not unlike AD, the pathogenesis of PD is also complex and multifaceted, mainly characterized by the accumulation of α-synuclein aggregates to form Lewy bodies, autophagy dysfunction, mitochondrial dysfunction, neuroinflammation, and breakdown of the blood-brain-barrier. Asiatic acid has been found to be beneficial in alleviating the symptoms of PD by suppression of neuroinflammation, decrease in oxidative stress, regulation of mitochondrial dysfunction, inhibition α-synuclein translocation into mitochondria, prevention of apoptosis, and decrease in the expression of neuroinflammatory regulators in PD like α-synuclein, tyrosine hydroxylase, Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2), TLR4, and nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) [25–28].

Asiatic acid has demonstrated a neuroprotective effect on both lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced BV2 microglia cells as well as 1-methyl-4-phenyl-pyridine (MPP+)-induced SH-SY5Y cells [25]. These effects were thought to result from mitigation of the mitochondrial dysfunction and suppression of the inflammatory pathways. In MPP+-induced SH-SY5Y cells, which served as an in vitro PD model, asiatic acid (0.1–100 nM) exhibited neuroprotective effect on the dopaminergic neurons through a dual mechanism: suppression of activation of inflammasome NOD-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) by reduction in the mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) and regulation of mitochondrial dysfunction. Asiatic acid showed similar protective effects on the BV2 microglial cells by amelioration of mitochondrial dysfunction by reduction in the ROS and alteration of the mitochondrial membrane potential. These findings were supported by another report [28] in which asiatic acid has demonstrated neuroprotective effect against rotenone-induced neurodegeneration in SH-SYS5Y cells by mitigating mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress.

The association of α-synuclein with mitochondria is responsible for mitochondrial dysfunction, thereby contributing to apoptosis. In a study by Ding et al. [26] asiatic acid was shown to inhibit the translocation of α-synuclein into mitochondria and prevent the consequent oxidative stress and apoptosis in α-synuclein and rotenone-induced SH-SY5Y cells, which served as PD-like models. In a 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)- induced PD mice model, asiatic acid (40 mg/kg and 80 mg/kg) was found to exert neuroprotective effects by mitigation of apoptosis and inflammatory stress [27]. The anti-inflammatory activity of asiatic acid was evident from the reduced levels of ROS, nitric oxide (NO), 3-nitrotyrosine, IL-1β, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα), and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) in the striatum. Asiatic acid also exhibited anti-apoptotic effect which was linked to an increased in the expression of Bcl-2 and a decreased expression of Bax and caspase-3. Moreover, asiatic acid significantly inhibited the increased striatal expression of the neuroinflammatory regulators involved in PD, namely, α-synuclein, tyrosine hydroxylase, TLR2, TLR4, and NF-κB. The results indicated that asiatic acid has the potential to mitigate striatal inflammatory injury through the inhibition of α-synuclein/TLR/NF-κB pathways.

Cognitive impairment

Asiatic acid has been demonstrated to be a potent cognitive enhancer owing to its ability to promote neurogenesis [9, 11–13], decrease oxidative stress [9, 10, 14], and prevent mitochondrial dysfunction [10, 14] and neural apoptosis [14]. A research group led by Welbat et al. [9] conducted several studies to evaluate the effect of asiatic acid on cognitive impairment induced by 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and valproic acid in rat models [11–13]. Their findings demonstrated that asiatic acid not only prevents cognitive deficits but also promotes hippocampal neurogenesis. Oral administration of asiatic acid (30 mg/kg) for 20 days resulted in improved spatial memory, as shown by the novel object location test. Asiatic acid was found to reduce the levels of malondialdehyde (MDA), a marker of oxidative stress, in the hippocampus, indicating its antioxidant activity [9]. Furthermore, asiatic acid resulted in downregulation p21, a senescence marker protein, as well as upregulation of several neurogenesis markers, including Notch1, sex-determining region Y-box 2 (SOX2), nestin, doublecortin, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) and Ki-67. This suggests the ability of asiatic acid to promote neurogenesis. Thus, it can be inferred that the cognitive improvement may have resulted from asiatic acid’s dual action of reducing oxidative stress and promoting neurogenesis in the hippocampus. However, the authors emphasized that these beneficial effects could be obtained only with pre- or co-administration of asiatic acid in the chemotherapy treatment.

In addition to its reported neuroprotection against 5-FU and valproic acid-induced neurotoxicity, asiatic acid has also been shown to prevent neurotoxicity induced by quinolinic acid in rats [10]. In agreement with the previous studies, improvement in cognitive function and antioxidant activity was observed after administration of asiatic acid (30 mg/kg) for four weeks. Antioxidant activity was evident from a reduction in the levels of MDA as well as increase in the levels of antioxidant enzymes, namely superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx). Most notably, asiatic acid alleviated mitochondrial dysfunction, as shown by enhanced activities of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation complex I (NADH-dehydrogenase) as well as complex III (cytochrome-c-oxidase). Xu et al. [14] demonstrated the neuroprotective potential of asiatic acid against glutamate-induced cognitive impairment in both mice and the SH-SY5Y cell line (human neuroblastoma cells). The neuroprotective effect was believed to be due to its antioxidant and anti-apoptotic activities. Most importantly, asiatic acid prevented glutamate-induced mitochondrial dysfunction, as observed by the restored mitochondrial membrane potential as well as enhanced expression of mitochondrial regulators, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1α), and sirtuin 1 (Sirt1).

Neuroinflammation

The ability of asiatic acid to attenuate neuroinflammation has been supported by Park et al. [15] and Qian et al. [16]. Asiatic acid was found to be neuroprotective against methamphetamine (METH)-induced neuroinflammation in the SH-SY5Y cell line [15]. Pre-treatment of asiatic acid (20 μM) for 24 h caused significant suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNFR, TNFα, and IL-6, indicating its anti-inflammatory properties. Interestingly, asiatic acid inhibited the translocation of NF-κB p65 and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) from cytoplasm to the nucleus, as well as the phosphorylation of ERK, indicating a potential inhibition of the NF-κB-STAT3-ERK pathway. Additionally, asiatic acid was also found to inhibit the mitochondria-dependent apoptosis pathway, likely contributing to its anti-neurotoxic activity. Its anti-apoptotic effect was demonstrated by inhibition of the degradation of apoptosis regulator proteins caspase-3 and PARP, a decrease in the levels of Bax as well as increase in the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-xL. In another study [16], asiatic acid, at concentrations ranging from 0.1 µM to 100 µM, was found to suppress LPS-induced neuroinflammation in BV2 microglia cells by decreasing the production of NO as well as inflammatory cytokines (TNFα, IL-1, IL-6). These effects were suggested to be caused by asiatic acid-induced modulation of the Sirt1/NF-κB signaling pathway.

Epilepsy

Epilepsy is a neurological disorder characterized by recurrent seizures, stemming from sudden and uncontrolled electrical disturbances in the brain. The pathogenesis of epilepsy is complex and reported to involve genetic predisposition, altered ionic homeostasis, neurotransmitter imbalance, neuroinflammation, altered neurogenesis, and receptor dysfunction [38, 39]. Asiatic acid was found to attenuate kainic acid-induced seizures in mice [29]. Asiatic acid (20–40 mg/kg/day) was able to decrease seizure-like behavioral patterns in mice. It was found to reduce the production of inflammatory mediators, namely IL-1β, IL-6, TNFα, and PGE2, as well as the generation of glutathione disulfide (GSSG) and ROS, thereby mitigating oxidative stress. Asiatic acid also reduced the expression of Bax, preventing apoptotic injury. Furthermore, it reduced the levels of the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate, alleviating glutamate-induced oxidative stress and seizure-like behavior. Therefore, asiatic acid-mediated reduction in the levels of oxidative stress, glutamate, as well as inflammatory factors may have collectively contributed to the mitigation of seizures.

In 2021, Lu et al. [30] confirmed the neuroprotective effects of asiatic acid in kainic acid-induced seizures in rats. Pre-treatment with asiatic acid (15 mg/kg, 50 mg/kg) resulted in notable improvement in learning and spatial memory in the Morris water maze test. It resulted in the inhibition of activation of calpain, the calcium-dependent cysteine proteases implicated in apoptosis, together with upregulation of pAKT in the hippocampus. Moreover, asiatic acid caused a notable rise in the levels of synaptic proteins, including synaptophysin, synaptotagmin, synaptobrevin, synapsin-1 (Syn-1), SNAP-25, and postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD95). Thus, it can be concluded that the neuroprotective effect of asiatic acid in seizures may have resulted from the inhibition of activation of calpain as well as restoration of synaptic function.

Asiaticoside

Asiaticoside (Figure 3), the glycoside derivative of asiatic acid, has also been independently evaluated as a potential neuroprotective agent [40, 41]. Research has been primarily focused on its efficacy in management of neurodegenerative disorders such as AD [42–44], and PD [45–47]. Asiaticoside has also shown promise in alleviation of cerebral ischemia [48–50], SCI [51–53], and depression [54].

Alzheimer’s disease

Zhang et al. [42] discovered that asiaticoside can reverse the Aβ-induced cognitive impairments in the AD rat model. Following a seven-day oral treatment of asiaticoside at doses ranging from 5 mg/kg to 45 mg/kg, learning and memory function were notably improved in a dose-dependent manner. This was demonstrated by a significant decrease in the escape latency in the Morris water maze test. Post-asiaticoside treatment, Aβ accumulation in hippocampal tissue was greatly reduced, and the degenerative changes produced by Aβ were also reversed. Asiaticoside resulted in a remarkable decline in caspase-3 expression, which could potentially contribute to its protective effect against Aβ-induced neurotoxicity [42]. The noteworthy finding was that asiaticoside inhibited neuroinflammation, as evidenced by a decrease in the levels of IL-6 and TNFα. Several studies [42–44] have substantiated this anti-inflammatory effect of asiaticoside, which appears to be the key to its neuroprotective effect.

Dysfunction of the blood–brain barrier is linked with the development of AD. The blood-brain barrier is constituted by specialized human brain microvascular endothelial cells (hBMECs). Aβ peptides have been reported to induce apoptosis in the hBMECs, causing blood-brain barrier dysfunction. This may lead to aberrant transport of Aβ in the cerebral blood circulation and its excessive deposition in the brain, promoting the development of AD. In 2018, Song et al. [43] demonstrated that asiaticoside can prevent Aβ1–42-induced apoptosis in hBMECs, indicating its protective potential in the pathogenesis of AD. Pre-treatment with asiaticoside (25 μM, 50 μM, and 100 μM) for 12 h dramatically reduced the Aβ1–42-induced cell growth inhibition and apoptosis in hBMECs in a dose-dependent manner. Asiaticoside’s anti-apoptotic effect in hBMECs may be due to the suppression of the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway, as indicated by a reduction in the levels of key pathway proteins, including TLR4, myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88), tumor necrosis factor receptor associated factor 6 (TRAF6), and p-NF-κB p65, which were upregulated by Aβ1–42 [43].

Synaptic dysfunction manifests in the initial phases of AD and is associated with the onset of neurodegeneration. Aβ is one of the key factors that contribute to synaptic dysfunction. Liu et al. [44] have recently discovered that asiaticoside has the ability to improve synaptic dysfunction, therefore alleviating the pathogenesis of AD. Following the intragastric injection of asiaticoside (40 mg/kg/ per day) for 14 days, a marked enhancement in synaptic function was observed. This was evidenced by the increase in the level of PSD95, which serves as an indicator of synaptic function. Moreover, the asiaticoside-treated group exhibited decreased levels of TNFα, IL-β, and IL-1 in microglia, indicating anti-inflammatory activity, which was thought to be responsible for improved synaptic function. Bringing a hint of clarity to the mechanism underlying its anti-inflammatory property, they showed that asiaticoside downregulates growth arrest and DNA damage inducible bet (Gadd45b), a key mediator in the p38-MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) pathway, suggesting inhibition of this pathway.

Parkinson’s disease

Xu et al. [45] discovered that asiaticoside has the potential to attenuate MPTP-induced neurotoxicity in a rat model of PD by protecting dopaminergic neurons. Motor function significantly improved after 14 days of asiaticoside treatment at doses of 15 mg/kg, 30 mg/kg, or 45 mg/kg per day. This was evidenced by the open field test and ladder walking test, which showed an increase in the number of crossings and peripheral ambulation time, as well as a decrease in the immobilization time and running time. The most important finding is that asiaticoside was able to prevent the MPTP-induced decline in the striatal dopamine levels. In addition, asiaticoside exhibits an anti-apoptotic effect, as evidenced by increase in the Bcl-2/Bax ratio. This contributes to its neuroprotective effect on the dopaminergic neurons [45, 47].

Phosphoinositides (PI) signaling is involved in regulation of synaptic vesicular trafficking and synaptic integrity. Alteration in the synaptic vesicle trafficking pathways is implicated in neurodegeneration involved in PD. Rotenone alters the expression of the PI signaling proteins, which may contribute to its neurotoxic effects. Asiaticoside successfully mitigated rotenone-induced neurotoxicity in a rat model of hemiparkinsonism by maintaining the PI-mediated signaling and synaptic function [46]. It was able to restore the altered levels of PI signaling proteins, namely, Syn-1, syntaxin-1A (Stx-1A), PI3K, pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK), vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT-2), and phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein (PEBP) to normal levels. In addition, the asiaticoside-treated group exhibited increased expression of neurotrophins, namely brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and nerve growth factor (NGF), indicating its potential neurotrophic effect. The asiaticoside-treated group also showed higher levels of dopamine and glutamate, consistent with the findings reported by Xu et al. [45]. The antioxidant activity of asiaticoside also adds to its neuroprotective effect in PD, as shown by increase in the SOD, CAT, and glutathione (GSH) levels and decrease in the MDA and lipid peroxidation (LPO) levels in these studies [45, 46].

Astrogliosis plays an important role in the pathogenesis of PD. Recently, Sampath et al. [47] showed that asiaticoside exerts a protective effect against MPTP-induced neurotoxicity in a mouse model of PD by inhibiting the activation of astrocytes. This was evidenced by the lower level of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), an astrogliosis marker protein [47].

Cerebral ischemia

Sun et al. [49] investigated the neuroprotective potential of asiaticoside in an in vitro model of ischemia-hypoxia in neuronal cells. Following treatment with asiaticoside for 24 h (10 nM or 100 nM), there was a significant increase in the cell survival rate. Ischemic-hypoxic injury causes the release of a large amount of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), which was attenuated by asiaticoside in a dose-dependent manner. Most notably, the asiaticoside-treated group exhibited a notably reduced rate of cell apoptosis. Furthermore, there was a notable rise in the expression of Bcl-2 and a decrease in the expression of Bax and caspase-3. This suggests that the neuroprotective effect of asiaticoside in ischemic-hypoxic injury may be attributed to its anti-apoptotic properties [49].

Based on these findings, Zhou et al. [50] investigated the mechanism underlying asiaticoside’s neuroprotective effect using a hypoxic-ischemic brain injury rat model. They demonstrated that asiaticoside can ameliorate the ischemic-hypoxia-induced histological damage and apoptosis in the brain neuron tissue, consistent with findings reported by Sun et al. [49]. The asiaticoside-treated group showed a reduction in oxidative damage, as observed by lower levels of MDA and LDH. Additionally, there was a decline in the levels of pro-inflammatory factors, ICAM-1, IL-6, IL-18, and IL-1β. The most enlightening finding was the decreased expression of TLR4, phosphorylated NF-κB and STAT3, and TNFα, suggesting that asiaticoside may exert its neuroprotective effects via suppressing the TLR4/NF-κB/STAT3 signaling pathway [50].

Spinal cord injury

The pathophysiology of SCI is complex, encompassing both the initial primary injury and subsequent secondary injury. While both processes contribute to neurological dysfunction in SCI, secondary damage plays a predominant role. The acute phase of secondary injury involves vascular damage, hemorrhage, apoptosis, generation of free radicals, and accumulation of neurotransmitters, with neuroinflammation being the most pivotal factor. Therefore, prompt alleviation of inflammation following SCI is crucial for protecting neuronal tissue and promoting recovery.

Asiaticoside was shown to alleviate neuronal damage in SCI in several studies [51–53]. Luo et al. [51] evaluated the effect of asiaticoside in a SCI rat model in order to shed light on the mechanism underlying its neuroprotective effect. Following a seven-day treatment with asiaticoside at doses of 30 mg/kg or 60 mg/kg, motor function was notably improved, as shown by a higher score on the Basso-Beattie-Bresnahan locomotor rating scale. The asiaticoside-treated group showed a reduction in the levels of MDA, as well as an elevation in levels of SOD, GSH, and GPx, indicating anti-oxidant activity. Anti-inflammatory effect was also observed, as indicated by suppression in the levels of NF-κB p65 unit, TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-6. These antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities may be the key factors contributing to the protective effect of asiaticoside in SCI. These observations are supported by findings of Fan et al. [52]. Interestingly, the asiaticoside-treated group exhibited a marked reduction in the expression of p38-MAPK, suggesting that asiaticoside may cause suppression of the p38-MAPK pathway. Activation of the p38-MAPK pathway in SCI results in upregulation of MAPK and its associated downstream mediator, matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), leading to disruption of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and exacerbation of neuronal injury. Thus, asiaticoside-mediated downregulation of the p38-MAPK pathway may contribute to its neuroprotective effect [51].

Recently, Hu et al. [53] provided more evidence supporting this effect by demonstrating that asiaticoside prevents damage to the blood-spinal cord barrier (BSCB) by suppressing the MAPK pathway. The integrity of BSCB plays a vital role in the functional recovery following SCI. Activation of the MAPK pathway causes downregulation of the junctional proteins, causing disruption of BSCB and thereby aggravating the neuronal damage. The asiaticoside-treated group showed upregulation of the endothelial junction proteins and downregulation of the MMP-9, indicating inhibition of the MAPK pathway [53]. Fan et al. [52] have demonstrated that asiaticoside enhances motor function in the SCI rat model and exhibits anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects, consistent with the findings of Luo et al. [51]. Their research revealed an additional significant new finding. The neuronal growth promoter neuritin was found to be more highly expressed in the asiaticoside-treated group, suggesting that asiaticoside may have the ability to enhance neuronal growth and regeneration [52].

Madecassoside

Aside from asiaticoside, another important ursane-type triterpenoid derived from Centella asiatica is madecassoside (Figure 3), which is the glycoside of madecassic acid. Much like asiaticoside, it has also shown potential in management of AD, PD, epilepsy, and cerebral ischemia.

Alzheimer’s disease

Mamun et al. [55] demonstrated the protective effect of madecassoside against Aβ-induced neurodegeneration in vitro (SH-SY5Y cells) as well as in vivo using an AD rat model. AD is characterized by the deposition of Aβ peptides in the neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the brain. Madecassoside (20 μM) effectively suppressed the formation of Aβ1-42 fibrils, as demonstrated by the thioflavin T fluorescence assay. Co-administration of madecassoside (100 μM) significantly attenuated Aβ1-42-induced apoptosis in SHSY5Y cells in a concentration-dependent manner, in the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay. In the AD rat model, pre-administration of madecassoside orally (300 mg/kg) for 11 weeks resulted in a significant improvement in spatial memory, as demonstrated by the eight-arm radial maze test. This cognitive improvement may have resulted from the reduction of Aβ1-42 levels in the hippocampus, coupled with an upregulation of the neuronal plasticity regulators, BDNF, and PSD95. Furthermore, the madecassoside-treated group exhibited lower levels of LPO, TNFα, and cathepsin D in the hippocampus. Thus, based on findings of in vitro and in vivo studies, it can be inferred that madecassoside exhibits anti-apoptotic, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, cognitive enhancing, and neuronal plasticity regulating properties, contributing to its neuroprotective effects. Consistent with the findings of this study, Du et al. [56] also demonstrated anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory effect of madecassoside against Aβ25–35-induced neurodegeneration.

Recent studies have indicated that autophagy and inflammatory responses activated by Aβ are intimately linked to the pathogenesis of AD. Du et al. [56] demonstrated that madecassoside can inhibit Aβ25–35-induced inflammatory responses and autophagy in the mouse NG108-15 neural cell line. Madecassoside (10 μM) reduced the formation of autophagosomes induced by Aβ25–35, as indicated by a decrease in cytoplasmic vacuolization. Madecassoside’s neuroprotective effect against Aβ25–35-induced inflammation and autophagy may be attributed to the regulation of the class III PI3K/Beclin-1/Bcl-2 pathway, which acts as a stimulator of autophagy and plays an important role in inflammation-mediated autophagy. This was evidenced by the downregulation of the key pathway proteins, hVps34 and Beclin-1 as well as the inflammatory cytokines, TNFα, IL-10, IL-6, and cyclooxygenase (COX-2).

Madecassoside has also been found to ameliorate cognitive impairment induced by D-galactose in mice [57]. Following 12 weeks of oral administration of madecassoside (5 mg/kg, 10 mg/kg, or 20 mg/kg), spatial learning and memory deficits were significantly improved, as shown by the open field test as well as the Morris water maze test. This study suggested the suppression of NF-κB and ERK/p38-MAPK pathway as the underlying mechanism contributing to the neuroprotective effects of madecassoside. This was indicated by the decrease in the levels of NF-κB p65, ERK1/2, and p38. Consistent with Mamun et al. [55], this study also demonstrated the suppression of Aβ1-42 levels, upregulation of the neuronal plasticity regulators, and antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Furthermore, madecassoside exhibited a considerable rise in acetylcholine levels, suggesting its ability to restore cholinergic function and indicating its potential benefits in AD. Recently, madecassoside has also been found beneficial in alleviating neurodegeneration induced by deficiency of protein L-isoaspartyl methyltransferase (PIMT) in mice [58]. PIMT deficiency induced anxiety-like behavior, sleep disturbances, and synaptic dysfunction in mice that were alleviated by madecassoside.

Parkinson’s disease

Xu et al. [59] explored the neuroprotective properties of madecassoside in the MPTP-induced rat model of parkinsonism. This study investigated the effects of both one-week pre-treatment followed by two-week post-treatment with madecassoside. This experimental design allowed to evaluate the effect of madecassoside treatment prior to MPTP administration. The madecassoside-treated group exhibited enhanced locomotor function, as evidenced by a decrease in running time in the ladder walking test. The locomotor improvement could be attributable to higher dopamine levels, implying that madecassoside considerably reduced the MPTP-induced loss of dopamine in the striatum. Furthermore, consistent with other investigations, madecassoside-treated group had significantly lower striatal MDA levels as well as higher levels of GSH, Bcl-2/Bax ratio, and BDNF. These findings underline that madecassoside has neuroprotective benefits in PD owing to its antioxidant, anti-apoptotic, and neural plasticity-enhancing properties.

Cerebral ischemia

Madecassoside can exert a potent neuroprotective effect against cerebral ischemia-induced injury in rats, mediated by anti-oxidative, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic mechanisms. Luo et al. [60] showed that madecassoside can protect BV2 microglial cells in an in vitro ischemia model of oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD) followed by reperfusion (R). Pre-treatment with madecassoside (200 μM) attenuated OGD/R-induced cytotoxicity. Madecassoside (200 μM) reduced IL-1β, IL-6, and TNFα levels, indicating marked anti-inflammatory activity. This effect was evident even at lower concentrations of 100 μM and 50 μM. These neuroprotective properties of madecassoside were proposed to result from the suppression of the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB pathway. This was evidenced by the decrease in expression of the crucial proteins TLR4, MyD88, and NF-κB in BV2 microglia. These findings align with the results of previous studies [61, 62]. The neuroprotective effect of madecassoside in ischemic injury has also been confirmed in the GT1-7 cell lines [61].

Epilepsy

Excitotoxicity, a process of neuronal damage due to excessive stimulation of excitatory amino acid receptors, is one of the main molecular mechanisms underlying epileptic brain damage. Recently, Kunjumon et al. [63] developed madecassoside-encapsulated alginate chitosan nanoparticles (MACNPs) and evaluated their neuroprotective potential in the pilocarpine-induced seizure mice model. Co-administration of MACNPs (20 mg/kg) by intravenous route prevented pilocarpine-induced spontaneous motor seizures in all mice. This anti-excitotoxicity property of madecassoside was assumed to be exerted via the MAPK inflammatory pathway. This was evidenced by reduced expression of inflammatory mediators, Bcl-2, caspase-3, hspa1b, MAPK1, MAPK14, and p53 in the brains of mice treated with MACNP + pilocarpine compared to those treated with pilocarpine alone. These findings indicate madecassoside encapsulated nanoparticles may emerge as a viable therapeutic option for the management of epilepsy.

Neuroinflammation

The study by Liu et al. [64] showed that madecassoside can alleviate LPS-induced neurotoxicity in rats. Following pre-treatment with madecassoside (120 mg/kg) for 14 days by oral gavage, the LPS-induced memory deficits were reversed. Moreover, the levels of inflammatory cytokines, IL-6, IL-1β, and TNFα were significantly suppressed in the cortex and hippocampus. This anti-inflammatory effect of madecassoside was considered to be due to the activation of the kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1)-Nrf2/heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) signaling pathway as evidenced by the upregulation of Nrf2 and HO-1 and downregulation of Keap1 protein levels. Inhibition of the Nrf2 pathway is reported to increase oxidative stress damage in neurodegenerative diseases. Therefore, it can be concluded that madecassoside may be beneficial in ameliorating neuroinflammation associated with neurodegenerative disorders. In line with the results of this study, Sasmita et al. [65] have demonstrated the anti-neuroinflammatory effect of madecassoside against LPS-induced inflammation in BV2 microglia.

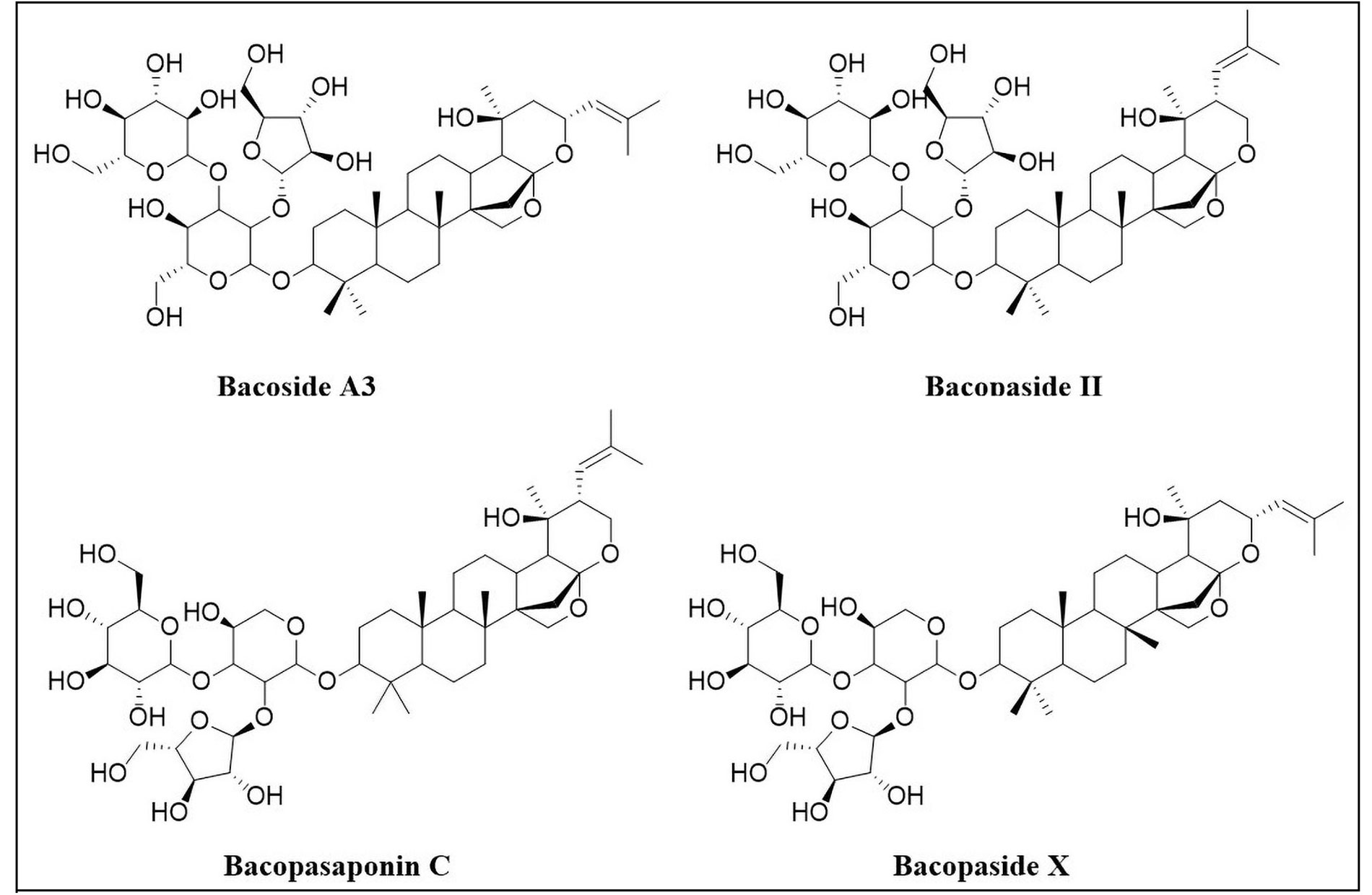

Bacoside A

Bacoside A (Figure 4) is a dammarane-type triterpenoid saponin obtained from Bacopa monnieri (Scrophulariaceae), a medicinal herb that has been extensively used as a neuromedicine. The primary nootropic components of Bacopa monnieri are known as bacosides, which contain jujubogenin or pseudo-jujubogenin moieties as their aglycone units [66]. Bacoside A, the vital neuroprotective constituent is a mixture of four saponins: bacoside A3, bacopaside II, bacopasaponin C, and bacopaside X (jujubogenin isomer of bacopasaponin C) [67, 68]. Bacoside A is demonstrated to be a potent neuroprotective owing to its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory and it has shown potential in the management of PD and epilepsy.

Components of bacoside A: bacoside A3, bacopaside II, bacopasaponin C and bacopaside X

Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity

A study comparatively evaluated the neuroprotective properties of four constituents of bacoside (bacoside A3, bacopaside II, bacopasaponin C, and bacopaside X) against oxidative stress induced by H2O2 on N2a neuroblastoma cells [69]. Bacoside A3 and bacopaside II were found to have a significant antioxidant activity than the other two components, namely bacopasaponin C, and jujobogenin, as shown by the 7-fold reduction in the levels of ROS. Moreover, bacoside A3 and bacopaside II were also found to have higher cytoprotective as well as anti-apoptotic activity. Bacoside A has been demonstrated to be a superior neuroprotective agent in terms of antioxidant activity when compared to asiatic acid and kaempferol against focal cerebral ischemia induced by endothelin-1 in rats [70]. Another study also showed that bacoside A has a protective effect on rat brains against oxidative stress induced by chronic cigarette smoking [71]. It was also reported to alleviate the dichlorvos-induced neurotoxicity in mice, as shown by decrease in the level of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances and protein carbonyl content [72]. The anti-inflammatory effect of bacoside-A was demonstrated in both acute and chronic experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis models. Bacoside A was shown to suppress the inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-17A, and TNFα) and chemokines chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5 (CCL-5) [73].

Neurodegenerative diseases

Bacoside-A has demonstrated the potential to be used in the management of PD, while its component bacoside-A3 has shown therapeutic potential for AD. Bacoside-A has been shown to have a protective effect against PD-induced oxidative damage and neuronal degeneration in rats. This was indicated by the downregulation of inducible NO synthase (iNOS), acetylcholinesterase (AChE), inflammatory cytokines, and pro-apoptotic proteins [74]. On the other hand, bacoside-A3 is shown to improve the pathogenesis of AD by causing a downregulating Aβ inflammatory response, preventing Aβ-mediated suppression of U87MG cell viability, inhibiting the generation of oxidative radicals, PGE2, and synthesis of iNOS in U87MG cells [75].

Epilepsy

Bacoside A was found to have antiepileptic activity by reducing the impairment of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)ergic activity, motor learning, and memory deficit. This effect was achieved through the downregulation of GABAA receptor subunits—GABAA1, GABAA5, and GABAAδ in the cerebellum of epileptic rats [76]. In further studies by Sekhar et al. [77] bacoside A nanoparticles were shown to exhibit antiepileptic activity by decreasing the expression of epileptic markers such as fractalkine, high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), forkhead box O3a (FOXO3a), and pro-inflammatory cytokines. Additionally, these nanoparticles were found to protect neurons from apoptosis and restored mitochondrial membrane potential [77].

Bacopaside I

Bacopaside I (Figure 3), a dammarane-type of triterpenoid obtained from Bacopa monnieri has been shown to exhibit notable neuroprotective effects in some conditions like PD, cerebral ischemia, and epilepsy. Bacopaside I showed a neuroprotective effect against rotenone induced rat PD model [78]. Following co-treatment with bacopaside I (5 mg/kg, 15 mg/kg, 45 mg/kg) for four weeks, motor function was notably improved as shown by rotarod, foot printing and grip strength tests. Bacopaside also increased the dopamine levels and reduced the oxidative stress. Moreover, upregulation of expression of dopamine transporter and VMAT was also observed which is crucial for dopaminergic neurons. A nanoformulation of bacopaside I was shown to have potential antiepileptic activity in kainic acid induced rat seizure model (in vivo) as well as in vitro using N2a cells [77]. Bacopaside I caused a marked reduction in epileptic episodes as well as downregulation of epileptic markers including fractalkine, HMGB1, FOXO3a, and pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Bacopaside I has also shown potential in the alleviation of cerebral ischemia transient focal ischemia in rats [79]. Following oral administration of bacopaside I (3 mg/kg, 10 mg/kg, or 30 mg/kg) per day, neurological deficits were greatly reduced. The cerebral infarct volume and edema were also decreased. Bacopaside I showed antioxidant activity, as demonstrated by improved activities of antioxidant enzymes including SOD, CAT, and GPx as well as a marked increase in the levels of MDA.

Ganoderic acids

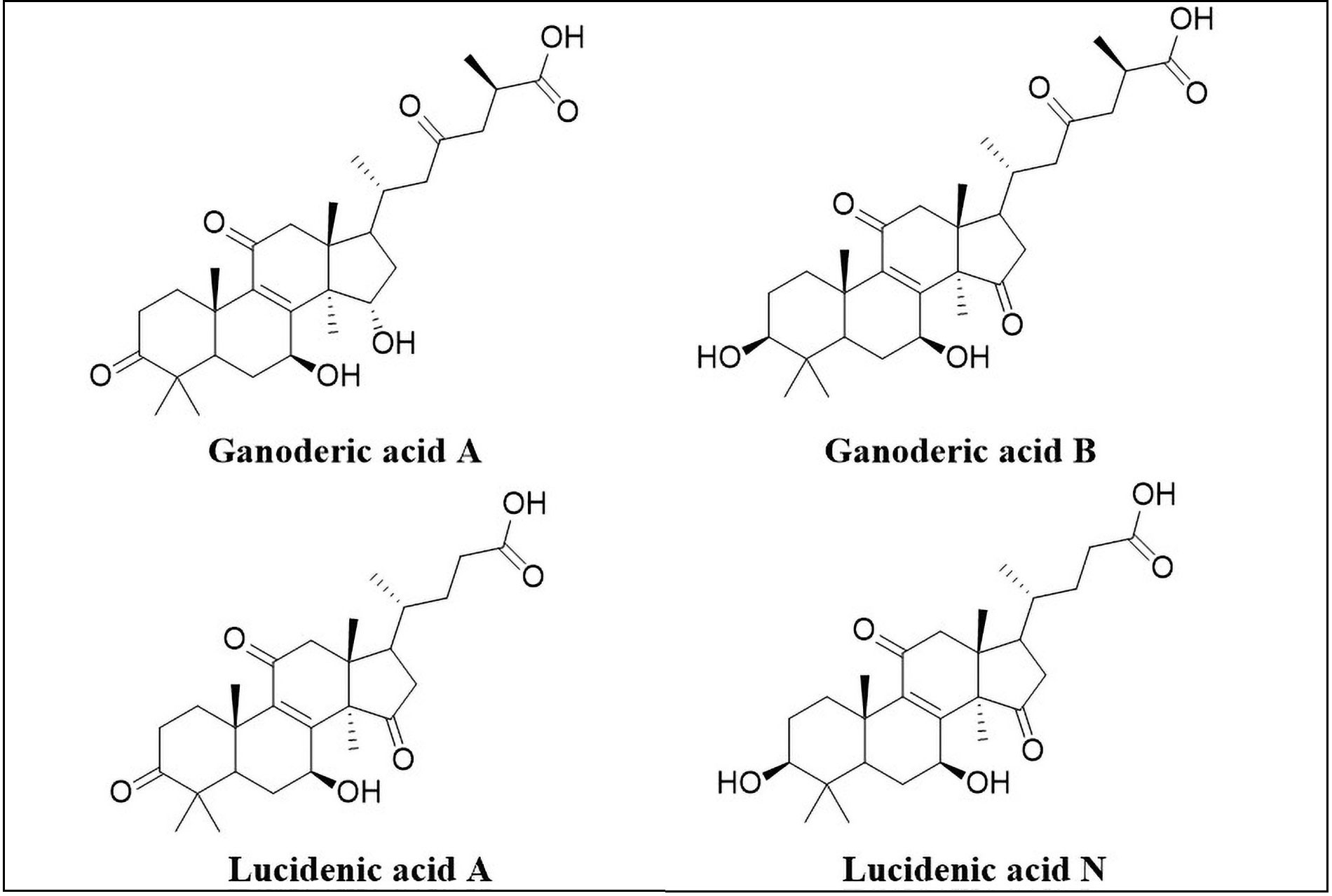

Ganoderic acids (Figure 5) are C30 lanostane-type tetracyclic triterpenoids isolated from mushroom Ganoderma lucidum. Mainly known for its immunomodulatory and anticancer activities, it is used in traditional Chinese medicine to promote health and longevity. Ganoderic acids, one of the major triterpenoid groups in G. lucidum, were revealed to possess neuroprotective activities with potential applications in AD, PD, epilepsy, and multiple sclerosis owing to their anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, and neurotrophic properties [80].

Structures of ganoderic acid A, ganoderic acid B, lucidenic acid A, lucidenic acid N

Alzheimer’s disease

Ganoderic acids have demonstrated therapeutic potential for AD by targeting Tau hyperphosphorylation, neuroinflammation, and Aβ clearance through various molecular mechanisms [81–83]. Abnormal hyperphosphorylation of Tau is one of the key pathological hallmarks of AD. Tau phosphorylation is associated with the induction of Bax and Bad, which in turn activate caspases and promote neuronal cell death. Recently, both ganoderic acids A and B were found to reduce okadaic acid-induced neurotoxicity in PC12 cells by inhibiting Tau hyperphosphorylation [81]. This was evident from the increased cell viability in the MTT assay. Pre-treatment with ganoderic acid A and B (12.5–50 μg/mL) significantly attenuated the okadaic acid-induced LDH leakage, Ca2+ levels, and caspase-3 activity. Marked inhibition of apoptosis was noted, as shown by downregulation of Bax and Bad expression. Ganoderic acid B was found to be more superior neuroprotective agent that ganoderic acid A, as it caused downregulation of both Bax and Bad proteins, whereas, ganoderic acid A was able to downregulate only Bax. Moreover, ganoderic acids A and B notably decreased the expression of pTau (S199) and pTau (T231), indicating inhibition of Tau phosphorylation at the critical sites. The inhibition of the GSK-3β pathway was suggested as a probable mechanism owing to the decreased levels of p-GSK-3β (Tyr216). Therefore, the results of this study support ganoderic acid B as a potential therapeutic compound for treating AD and other Tau-related neurodegenerative disorders.

Imbalance in the activity of Th17 and Tregs cells contributes to neuroinflammation in AD. Ganoderic acid A has been demonstrated to reduce AD-associated neuroinflammation in mice by regulating the imbalance of the Th17/Tregs axis [82]. The authors hypothesized that Ganoderic acid may potentially inhibit the janus kinase (JAK)/STAT pathway induced by Th17 while simultaneously enhancing the mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation by regulating Treg cells, thereby restoring balance of Th17/Tregs activity. In the in vitro study, ganoderic acid A was found to facilitate the degradation and elimination of Aβ42 in BV2 microglial cells [83]. This activity was shown to be a result of the enhancement of autophagy via the Axl/Pak1 signaling pathway by ganoderic acid A. Moreover, ganoderic acid A was also found to ameliorate the cognitive deficits in the AD mouse model.

Parkinson’s disease

Ganoderma lucidum is being used since a long time for alleviating symptoms of neurodegenerative diseases including PD. Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent manner of cell death and is recognized as a significant contributor to the loss of dopaminergic neurons in PD. The primary factor implicated in ferroptosis is nuclear receptor coactivator 4 (NCOA4)-mediated ferritinophagy. To gain a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the neuroprotective effect of ganoderic acid A in PD, Li et al. [84] evaluated its effect in MPP+/MPTP-induced PD models. Ganoderic acid A was shown to mitigate MPP+/MPTP-induced neurotoxicity, motor dysfunction, and dopaminergic neurons loss both in vitro as well as in vivo. Moreover, ganoderic acid A was also found to inhibit MPP+/MPTP-induced neuronal ferroptosis and NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy.

Epilepsy

Ganoderic acid A showed notable antiepileptic activity in pentylenetetrazole induced epileptic rat model [85]. Following post-treatment with ganoderic acid A (10 mg/kg) for one week by intragastric route, a significant reduction in the epileptic behavior was observed along with the increase in seizure latency and a decrease in the seizure duration. TUNEL assay showed notable reduction in apoptosis rate, upregulation of Bcl-2 as well as downregulation of Bax. These effects were believed to have resulted from activation of the MAPK pathway and may have contributed to its neuroprotective effect. Ganoderic acid extract has also demonstrated a neuroprotective effect in magnesium-free induced epilepsy in primary hippocampal neurons. The antiepileptic activity of ganoderic acid A has also been supported by Yang et al. [86] in 2016. In this study, ganoderic acid A (20/80/320 μg/mL) has demonstrated a significant reduction in apoptotic hippocampal neurons causing epileptiform discharge. Its antiepileptic activity was attributed to the upregulation of BDNF and transient receptor potential channel 3 (TRPC3) which have neuronal protective effects.

Cognitive impairment

Ganoderic acid A was shown to prevent 5-FU-induced cognitive dysfunction in mice [87]. Behavioral studies revealed that ganoderic acid A prevented the reduction of spatial and non-spatial memory. Moreover, it was also found to upregulate the expression of proteins associated with nerve growth and survival such as BDNF, phosphorylated ERK (pERK), phosphorylated cAMP response element-binding protein (pCREB), pAKT, pGSK-3β, Nrf2, pmTOR, and pS6, in the hippocampus of these mice. Thus, in addition to having neuroprotective effect, ganoderic acid A can also be used as a cognitive enhancer in neurodegenerative disorders.

Lucidenic acids

Lucidenic acids (Figure 5), the C27 lanostane-type of tetracyclic triterpenoids, are the second major group of Ganoderma triterpenoids. Twenty-two types of lucidenic acids have been discovered so far. Lucidenic acids have potential anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant, anti-viral, anti-obesity, anti-diabetic, neuroprotective, and immunomodulatory properties [88, 89]. In 2011, the neuroprotective potential of lucidenic acids became apparent for the first time when lucidenic acids isolated from the fruiting bodies of G. lucidum were found to be selective inhibitors of AChE in an in vitro study [90]. This study opened the possibility of their potential utilization for alleviating symptoms associated with AD. Lucidenic acids A and N were found to inhibit AChE with IC50 values of 24.04 μM ± 3.46 μM and 25.91 μM ± 0.89 μM respectively, in comparison to berberine chloride (known inhibitor of AChE) with IC50 value of 0.04 μM ± 0.01 μM. A lucidenic acid derivative, methyl lucidenate E2 showed slightly better activity with an IC50 value of 17.14 μM ± 2.88 µM. In addition, lucidenic acids exhibited no butyrylcholinesterase (BChE)-inhibitory effect at concentrations up to 200 μM with the exception of lucidenic acid N which showed weak inhibition of BChE (IC50 = 188.36 μM ± 3.05 μM). This makes them selective inhibitors of AChE, suggesting that they might have no significant side effects attributable to BChE inhibition in clinical use. These results were supported by another in vitro study [91] in which lucidenic acid A inhibited AChE with an IC50 of 54.5 µM.

G. lucidum basidiocarp extracts containing lucidenic acids have also been evaluated for their AChE and tyrosinase inhibitory activity [92]. The basidiocarp extract obtained from wheat straw showed moderate activity with an IC50 of 0.56 mg/mL in comparison to AChE inhibitor galantamine, which demonstrated a more potent activity with an IC50 of 0.03 mg/mL. It can be concluded that the neuroprotective potential of lucidenic acids as selective inhibitors of AChE offers a promising avenue for addressing AD symptoms and needs further investigation.

Clinical evidence

As evident from the discussion so far, a number of triterpenoids have demonstrated promise in pre-clinical research for neuroprotection; yet, only a small number of these compounds have advanced to clinical trials (Table 2). Two clinical trials demonstrated the beneficial effects of Ginsenoside Rd in acute ischemic stroke [93, 94] (Table 2, entries 1 and 2). Similarly, Licorice whole extract has also exhibited improvement in acute ischemic stroke [95] (Table 2, entry 4). Centella asiatica selected triterpenes (CAST) were shown to reduce the severity of symptoms of diabetic neuropathy [96] (Table 2, entry 3). Bacopa monnieri has been studied for both its effect on working memory in healthy high school students (Table 2, entry 5) and its efficacy in the treatment of schizophrenia (Table 2, entry 6). However, the results of these trials are not yet published. Although these clinical studies have demonstrated the neuroprotective potential of triterpenoids, the relatively small number of subjects in these studies is the main limitation. There is a need for a more rigorous and systematic evaluation in the form of clinical trials to validate these findings.

Clinical studies supporting the neuroprotective applications of triterpenoids

| SN | Triterpenoid under study | Year | Condition | Type | Subjects | Duration | Findings | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ginsenoside Rd | 2009 | Acute ischemic stroke | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2, multicenter trial | 199 | 14 days |

| [94]Clinical trial ID NCT00591084 |

| 2 | Ginsenoside Rd | 2012 | Acute ischemic stroke | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3, multicenter trial | 390 | 14 days |

| [93]Clinical trial ID NCT00815763 |

| 3 | Centella asiatica selected triterpenes (CAST) | 2022 | Diabetic neuropathy | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2, trial | 43 | 52 weeks |

| [96]Clinical trial ID NCT00608439 |

| 4 | Licorice whole extract | 2016 | Acute ischemic stroke | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2, trial | 75 | 7 days |

| [95]Clinical trial ID NCT02473458 |

| 5 | Bacopa monnieri extract | 2017 | Healthy | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1, trial | 75 | 16 weeks | NA | Clinical trial ID NCT02931747 |

| 6 | Bacopa monnieri extract | 2007 | Schizophrenia | Randomized, open label, phase 2, trial | 200 | 4 weeks | NA | Clinical trial ID NCT00483964 |

SN: serial number; NIHSS: National Institute of Health stroke scale; NA: not available

One of the main limitations of triterpenoids that prevents them from moving on to the clinical trial stage is their low oral bioavailability and limited penetration in the brain. In order to overcome these limitations, many synthetic derivatives of triterpenoids are being developed and evaluated for their neuroprotective potential. Several semisynthetic derivatives have shown promising results. For example, synthetic celastrol analogs [97], an oleanolic acid derivative, namely, 2-cyano-3, 12-dioxoolean-1, 9-dien-28-oic acid (CDDO), CDDO derivatives [98], ursolic acid and oleanolic acid derivatives [99] may prove to be potential candidates in future for the treatment of neurological disorders.

Future directions

Several promising avenues emerge in the future directions of research on the neuroprotective prospects of triterpenoids. Although numerous studies have investigated and shed some light on the mechanisms underlying their neuroprotective activities, the precise mechanisms are still unknown. Investigating the mechanisms underlying the neuroprotective properties in greater depth, particularly at the molecular and cellular levels, is needed to harness their therapeutic potential. Several artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML)-based techniques can be employed for this purpose. Bioinformatics and computational modeling employ AI-ML algorithms that can analyze large datasets of triterpenoid structures and correlate them with their biological activities. Molecular docking studies use algorithms that can predict the binding modes of triterpenoids with target proteins or enzymes. Integrative systems biology approaches combine experimental data with computational modeling to understand the complex interactions between triterpenoids and biological systems. This includes network analysis, pathway modeling, and dynamic simulations to unravel the signaling pathways and cellular processes affected by triterpenoids. “Omics” technologies including transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics can provide comprehensive insights into the effects of triterpenoids on gene expression, protein abundance, and metabolic pathways in biological systems.

One major area where research should be focused is on optimizing the use of triterpenoids for personalized medicine. One of the approaches can be to explore the synergistic effects of triterpenoids with other natural compounds as it could offer enhanced neuroprotective outcomes. Additionally, the development of novel delivery systems to improve the bioavailability and penetration of CNS could facilitate the transition of triterpenoids from preclinical studies into clinical trials and could enhance their efficacy in clinical applications. Furthermore, cutting-edge techniques like AI-powered metabolomics, pharmacogenomics, microbiome analysis, and genetic profiling can be used to maximize the utilization of triterpenoids in personalized medicine.

Conclusions

Triterpenoids represent a promising class of natural compounds with significant neuroprotective potential against various neurological disorders. Their multifaceted pharmacological properties, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic activities, have been supported by substantial evidence from the preclinical studies. However, despite the considerable progress made in elucidating their neuroprotective mechanisms, several challenges and unanswered questions remain. These include the need for further elucidation of precise mechanisms of action of triterpenoids in neuroprotection, the structure-activity relationships of different triterpenoids, and optimization of delivery methods to enhance their bioavailability and brain penetration. Integrating experimental data with AI-ML-based techniques such as bioinformatics and computational modeling, molecular docking, integrative systems biology, and omics technologies can prove to be pivotal in unraveling the mechanism of action of triterpenoids. Moreover, AI-powered metabolomics, pharmacogenomics, microbiome analysis, and genetic profiling can be used to optimize the use of triterpenoids in personalized medicine.

So far, only a small number of triterpenoids, such as ginsenoside Rd, Centella asiatica selected triterpenes, licorice extract, and Bacopa monnieri extract have been investigated for their neuroprotective potential in clinical trials. Many of the triterpenoids have not progressed to clinical trials owing to their poor oral bioavailability and limited brain penetration. Thus, development of novel delivery systems to improve the bioavailability and penetration to CNS is crucial to harness the therapeutic potential of triterpenoids. Furthermore, structural modifications of triterpenoids are likely to provide new leads in developing and synthesizing derivatives that overcome these limitations. Several synthetic triterpenoid derivatives, including celastrol analoges, CDDO and its derivatives, and derivatives of ursolic acid and oleanolic acid, have demonstrated encouraging outcomes in pre-clinical studies and might potentially serve as viable options for the treatment of neurological conditions in the future. Thus, natural and synthetic derivatives of triterpenoids may serve as both therapeutic and neuroprotective agents in neurological disorders.

Abbreviations

| 5-FU: | 5-fluorouracil |

| AChE: | acetylcholinesterase |

| AD: | Alzheimer’s disease |

| AI: | artificial intelligence |

| Aβ: | β-amyloid |

| Bax: | Bcl-2-associated X protein |

| BChE: | butyrylcholinesterase |

| BDNF: | brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| BSCB: | blood-spinal cord barrier |

| CAT: | catalase |

| CDDO: | 2-cyano-3, 12-dioxoolean-1, 9-dien-28-oic acid |

| ERK1/2: | extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 |

| GABA: | γ-aminobutyric acid |

| GPx: | glutathione peroxidase |

| GSH: | glutathione |

| GSK-3β: | glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta |

| hBMECs: | human brain microvascular endothelial cells |

| LDH: | lactate dehydrogenase |

| LPS: | lipopolysaccharide |

| MAPK: | mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MDA: | malondialdehyde |

| ML: | machine learning |

| MPP: | 1-methyl-4-phenyl-pyridine |

| MPTP: | 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine |

| MyD88: | myeloid differentiation primary response 88 |

| NF-κB: | nuclear factor-kappa B |

| NO: | nitric oxide |

| Nrf2: | nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| PD: | Parkinson’s disease |

| PGE2: | prostaglandin E2 |

| PI: | phosphoinositides |

| PSD95: | postsynaptic density protein 95 |

| pTau: | phosphorylated Tau |

| ROS: | reactive oxygen species |

| SCI: | spinal cord injury |

| SOD: | superoxide dismutase |

| STAT3: | signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| TLR2: | Toll-like receptor 2 |

| TNFα: | tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

Declarations

Acknowledgments

Ms. Apoorva A. Bankar would like to acknowledge University Grants Commission (UGC), New Delhi for providing fellowship for doctoral studies.

Author contributions

AAB: Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. VPN: Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing. NRK: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation. NNI: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2024.