Affiliation:

Instituto de Biomarcadores de Patologías Moleculares, Universidad de Extremadura, 06006 Badajoz, Spain

Email: biocgm@gmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3673-7007

Explor Neurosci. 2025;4:100672 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/en.2025.100672

Received: December 19, 2024 Accepted: February 10, 2025 Published: February 24, 2025

Academic Editor: Ryszard Pluta, Medical University of Lublin, Poland

The article belongs to the special issue Alzheimer's Disease

Intracellular amyloid β oligomers (AβOs) have been linked to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathogenesis and to the neuronal damage in this neurodegenerative disease. Calmodulin, which binds AβO with very high affinity, plays a pivotal role in Aβ-induced neurotoxicity and has been used as a model template protein for the design of AβO-antagonist peptides. The hydrophobic amino acid residues of the COOH-terminus domain of Aβ play a leading role in its interaction with the intracellular proteins that bind AβO with high affinity. This review focuses on Aβ-antagonist hydrophobic peptides that bind to the COOH-terminus of Aβ and their endogenous production in the brain, highlighting the role of the proteasome as a major source of this type of peptides. It is emphasized that the level of these hydrophobic endogenous neuropeptides undergoes significant changes in the brain of AD patients relative to age-matched healthy individuals. It is concluded that these neuropeptides may become helpful biomarkers for the evaluation of the risk of the onset of sporadic AD and/or for the prognosis of AD. In addition, Aβ-antagonist hydrophobic peptides that bind to the COOH-terminus of Aβ seem a priori good candidates for the development of novel AD therapies, which could be used in combination with other drug-based therapies. Future perspectives and limitations for their use in the clinical management of AD are briefly discussed.

The 2022 world Alzheimer’s report [1] pointed out the importance of early detection and diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), as nearly 75% of individuals with dementia are not diagnosed globally. The histopathological hallmarks of AD are the extracellular amyloid β (Aβ) plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles [2]. Aβ monomers aggregate to form low molecular weight oligomers (dimers, trimers, tetramers, and pentamers), mid-range molecular weight oligomers (hexamers, nonamers, and dodecamers), protofibrils, and fibrils [3]. Of special relevance for the main aims of this work is that the hydrophobic C-terminal of the Aβ plays a critical role in triggering the transformation from α-helical to β-sheet structure present in high-order aggregation states of Aβ found in AD [4]. Guo et al. [5] reported that Aβ and tau form soluble complexes that may promote self-aggregation of both into the insoluble forms observed in AD, and that middle and C-terminal Aβ regions provide the Aβ amino acid residues more strongly binding to tau, namely, peptide sequences Aβ(11–16), Aβ(27–32), and Aβ(37–42). Therefore, Aβ:tau complexes can be formed when intracellular free Aβ monomers/oligomers reach concentrations in the saturation range for the formation of these complexes. Moreover, Guo et al. [5] hypothesized that in AD the intracellular binding of soluble Aβ to soluble no phosphorylated tau promotes tau phosphorylation and Aβ nucleation, and proposed that blocking the sites where Aβ initially binds to tau might arrest the simultaneous formation of plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in AD. Other molecular mechanisms linking Aβ and tau pathology are reviewed in [6]. Also, it should be noted that the release of intracellular Aβ to the extracellular medium caused by the neuronal damage elicited by the toxic intracellular Aβ oligomers (AβOs) and neurofibrillary tangles is likely to potentiate Aβ plaque formation.

The neurotoxic Aβ peptide Aβ(1–42), which is found in higher concentrations in the brain of AD patients and associated with Aβ plaques [7, 8], is produced from the amyloid precursor protein (APP) by the so-called Amyloidogenic Pathway through the sequential activity of β-site APP cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1) and γ-secretase [9]. Indeed, an enhanced activity of BACE1 and a shift towards the amyloidogenic pathway of APP processing has been reported to be linked to several factors known to foster the neurodegeneration in AD-affected brains, like iron dyshomeostasis [10–12], brain oxidative stress [13–15], hypercholesterolemia [16–18], and brain hypoxia [19]. Furthermore, Aβ plaques and neurofibrillary tangles contain high concentrations of iron and Fe2+ and Fe3+ interactions with APP and Aβ speed up Aβ aggregation into fibrillar forms [12, 14, 20]. Nevertheless, nearly all BACE1 inhibitors used as candidate therapeutic agents in AD have failed in later phases of clinical trials, due to safety and/or efficacy issues, and others were discontinued early in favor of second-generation small-molecule candidates [21]. Thus, exploration of alternate approaches to reducing Aβ toxicity seems a timely issue. Indeed, it has been noted recently that phytochemicals like indole-3 carbinol and diindolylmethane that inhibit Aβ-induced neurotoxicity, Aβ self-aggregation, and acetylcholinesterase enzyme activity show anti-AD effects [22]. Another novel potential therapeutic target for AD is the attenuation of signaling pathways leading to Aβ overproduction, such as the WNT-β catenin signaling [23]. As reviewed in [23], the dickkopf WNT signaling pathway inhibitor 1 (DKK1), which promotes Aβ production and synapse degradation through downregulating WNT-β catenin signaling, colocalizes in neurofibrillary tangles and dystrophic neurites in post-mortem AD brains.

The shortest Aβ(1–42)-derived peptide that retains the toxicity of the full-length peptide is Aβ(25–35) [24], and this experimental observation is of relevance for the identification of peptides that can antagonize the actions of neurotoxic Aβ peptides. Cumulative experimental evidence shows that intracellular AβOs are linked to AD pathogenesis and are the cause of neuronal damage [25–27]. Indeed, the metabolic and neurotoxic effects of Aβ(1–42) have been linked with neuronal uptake of AβO and the subsequent intracellular rise of their concentration [26–28]. Furthermore, it has been proposed that amyloid plaques can be considered reservoirs of Aβ neurotoxic species [29]. As anti-Aβ antibodies are expected to trap only extracellular Aβ, this could, at least in part, account for the limited and partial protection reported for aducanumab treatment in AD [30]. It has been shown that binding of extracellular Aβ(1–42) to lipid rafts of the plasma membrane elicits its oligomerization (to dimers or trimers) and uptake by the neuronal cells in culture, reviewed in [31]. It is to be recalled here that (i) the apolipoprotein E4 (apoE4) allele is a major genetic risk factor for late-onset AD [32], (ii) apoE binds with high affinity extracellular Aβ(1–42) oligomers and the complex apoE:Aβ(1–42) has been reported to strongly co-localize with lipid rafts [33], and (iii) apoE4 exacerbates the intraneuronal accumulation of Aβ and plaque deposition in the brain parenchyma [34, 35]. Of note, α7 nicotinic cholinergic receptor and receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) are other proteins that have been proposed to play a role in neuronal Aβ uptake through binding with high affinity extracellular AβO [31].

Briefly, in the brain undergoing degeneration in AD, AβO is produced by neurons and, also, by reactive neurotoxic astrocytes [36, 37]. Thus, AβO dynamics between extracellular and intracellular spaces, i.e., the balance between neuronal uptake and secretion, plays a relevant role in AβO neurotoxicity. Only a few hours of incubation with 2 micromolar of Aβ(1–42) oligomers is needed to allow for a significant internalization of Aβ(1–42) in primary cultures of cerebellar granule neurons and in the HT-22 neuronal cell line [38, 39]. Internalized Aβ(1–40) and Aβ(1–42) peptides display a widespread intracellular distribution up to the perinuclear region in cerebellar granule neurons [38], in HT-22 cells [39], in differentiated PC12 cells and in rat primary hippocampal neurons [40], and in the neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y [41].

Thus, intracellular proteins that bind AβO with high affinity play a major role in Aβ-induced neurotoxicity, and antagonists of their interactions with AβO are expected to provide neuroprotection against Aβ-induced brain neurodegeneration. In the next section of this review, it is highlighted that the interaction of AβO with calmodulin (CaM), one of the intracellular proteins displaying higher affinity to AβO (if not the highest), can play a pivotal role in Aβ-induced neurotoxicity. The following section points out that highly hydrophobic peptides binding to the COOH-terminus of Aβ(1–42) inhibit the formation of Aβ(1–42):CaM complexes, and, also, the aggregation and neurotoxicity of Aβ. These are called Aβ-antagonist hydrophobic neuropeptides. The brain endogenous neuropeptides of this type that have been reported to suffer significant variations in AD are analyzed next. Future perspectives on the AD therapeutic potential of Aβ-antagonist hydrophobic neuropeptides are briefly dealt with in the final section of this review.

Patients with symptoms ranging from mild cognitive impairment to early mild AD suffer a progressive loss of functional synapses in hippocampal and cortical brain regions [42–44]. Neurotransmitter secretion, synaptic plasticity, neurite growth and sprouting, and signaling pathways that mediate the metabolic neuronal responses to many relevant extracellular stimuli are strongly dependent on cytosolic calcium concentration [45, 46]. In addition, mitochondrial Ca2+ signaling is altered in familial AD due to mutations in the presenilins [47], and this has been proposed to cause mitochondria dysfunction [48]. Furthermore, it has been shown that mutations in presenilins and APP can produce a substantial increase in the endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria connectivity through upregulation of the mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membrane functions, a common feature in both familial and sporadic AD [49, 50]. Indeed, a sustained increase in mitochondrial Ca2+ concentration impairs ATP production, increases reactive oxygen species production, and the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore [51].

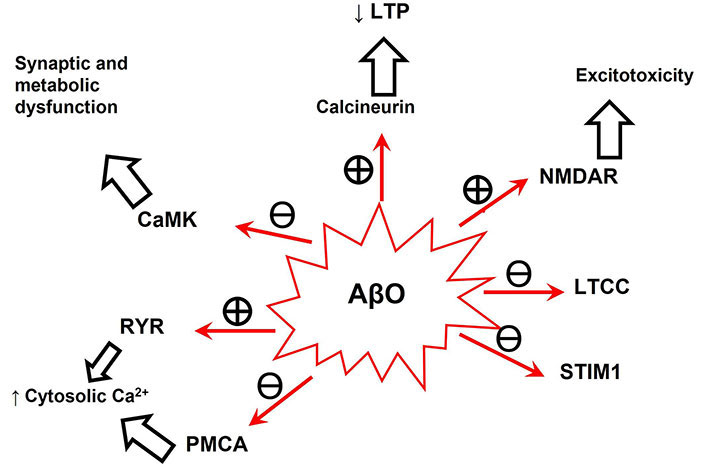

Many studies have shown that the activity of systems playing key roles in the control of neuronal intracellular calcium homeostasis and signaling are altered by AβO, reviewed in [52]. It is worth noting here that CaM binding proteins (CaMBPs) are major targets for intracellular AβO, as schematically shown in Figure 1, see also [53]. It is to be highlighted that at normal neuronal resting cytosolic calcium concentrations, i.e., ≤ 100 nM, CaM is mainly in the apo-CaM conformation [46]. Therefore, a dysregulation of intracellular calcium homeostasis that raises the cytosolic calcium concentration shifts the apo-CaM/Ca2+-CaM equilibrium towards the Ca2+-CaM conformation, which is the CaM conformation that binds to most CaMBPs. This bears a special relevance because, due to the high reactivity and short lifetime of reactive oxygen species produced by iron-Aβ redox cycling [14, 20], its relative proximity to the iron-Aβ source will determine the extent of oxidative modifications of these calcium transport systems.

Neuronal intracellular calcium signaling systems whose activity has been shown to be modulated by AβO. See [39, 52] for detailed references of each calcium signaling system modulation by AβO. The encircled + and ─ mean stimulation and inhibition, respectively. The ↑ and ↓ mean increase and decrease, respectively. AβO: amyloid β oligomer; CaMK: calmodulin-dependent kinase; LTCC: L-type calcium channels; LTP: long-term potentiation; NMDAR: N-methyl D-aspartate receptor; PMCA: plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPases; RYR: ryanodine receptor; STIM1: stromal interaction molecule-1

In addition, as briefly explained below, AβO induces a harmful feedback loop that fosters Aβ production. In vitro experiments have shown that BACE1 is stimulated around 2.5-fold by Ca2+-CaM [53, 54]. Moreover, Giliberto et al. [55] showed that the treatment of neuronal and neuroblastoma cells with 1 μM soluble Aβ(1–42) increased BACE1 transcription and that this was reverted by an anti-Aβ(1–42) antibody. It has been suggested that this could be due to Aβ-induced oxidative stress because this increase in BACE1 transcription was shown to be mediated by the activity of nuclear factor kappa light-chain enhancer of activated B cells (NFκB) [56].

Only a few intracellular proteins expressed in neurons are known to bind Aβ peptides with nanomolar dissociation constants. These are cellular prion protein [57], glycogen synthase kinase 3α [58], tau [5], stromal interaction molecule-1 (STIM1) [39], and the EF-hand calcium binding proteins CaM [59], and calbindin-D28k [60]. The nanomolar dissociation constant of the CaM:Aβ(1–42) complex [in Aβ(1–42) monomer concentration] reported by Corbacho et al. [59] from fluorescence studies, has been confirmed by Kim et al. [61] using titration microcalorimetry. As these dissociation constants were obtained using solutions of AβO (dimers/trimers), the CaM:Aβ(1–42) oligomers dissociation constant is < 1 nM AβO [59], implying that CaM is the intracellular protein with the highest affinity for AβO reported until now. This bears a special relevance, because the expression level of CaM in neurons (in the micromolar range) is several orders of magnitude higher than that of the other protein targets displaying a high affinity for Aβ(1–42), with the exception of calbindin-D28k in brain regions more prone to neurodegeneration in AD, namely, pyramidal neurons of hippocampus and in cortical neurons of the central nervous system. Moreover, extensive co-localization of internalized Aβ(1–42) and CaM in cerebellar granule neurons, and, also, co-immunoprecipitation of CaM with Aβ(1–42) in cell lysates strongly suggested that CaM is a major intracellular sink for Aβ(1–42) [38]. On these grounds, we have proposed that CaM and calbindin-D28k help to maintain the intracellular free neurotoxic Aβ concentrations in the low nanomolar range, i.e., serve as Aβ-trap or Aβ-buffer system [38, 52, 60].

The rational design of peptides to antagonize the interaction of AβO with target proteins in the neurons requires the knowledge of the three-dimensional structure of the target proteins with resolution at the atomic level, and, also, the amino acid residues of AβO more relevant for the formation of the complex between AβO and the target protein. Due to this, soluble target proteins become the first choice for this task, since the three-dimensional structures of only a few membrane-inserted proteins have been resolved at an atomic level, and their conformations can be significantly affected by their interaction with vicinal lipids in the native cell membrane. In addition, the smaller the protein size the better to minimize the possibility of the presence of alternate binding sites with different affinity for AβO. CaM, a small size soluble target protein with high affinity for AβO, fulfills these basic criteria.

In addition, CaM seems a good model protein template for the search for peptides that can antagonize Aβ(1–42) neurotoxicity because the two most recognized neuropathological hallmarks of AD, i.e., Aβ and tau, bind CaM with high affinity. Moreover, the activities of CaM-dependent kinase II (CaMKII), cyclin-dependent kinase 5, and glycogen synthase kinase 3α (protein kinases that contribute to tau hyperphosphorylation in AD) are modulated by CaM [52].

Salazar et al. [60] concluded that hydrophobic interactions drive the formation of the Aβ(1–42):CaM complex. Extensive docking analysis was performed in Salazar et al. [60] using the three-dimensional structure of CaM saturated by Ca2+ [Protein Data Bank file identification code (PDB ID): 1CLL] because Corbacho et al. [59] previously showed that the Ca2+-CaM conformation displays more than 10-fold higher affinity for AβO than apo-CaM. Since hydrophobic domains of CaM are more exposed in the Ca2+-CaM conformation than in the apo-CaM conformation, the latter result gives experimental support to their critical role in the complexation between CaM and Aβ(1–42). Hydrophobic amino acids of the COOH-terminus domain of Aβ, i.e., 24–42 amino acid residues of Aβ were identified as those more strongly interacting with CaM using interface analysis of the more probable structures generated by docking for the Aβ(1–42):CaM complex [60]. Using multi-tilt nanoparticle-aided cryo-electron microscopy sampling, Kim et al. [61] have reported that the complexation with Aβ(1–42) elicits structural changes in Ca2+-CaM, which is shifted to a structure intermediate between the classical Ca2+-CaM and apo-CaM conformations. This provides a rational basis to explain, at least in part, the modulation of CaMBPs by Aβ(1–42), a point that needs further experimental studies to be demonstrated. Another point that merits a brief comment is the presence of several methionines of CaM among the more strongly interacting amino acid residues with Aβ(1–42) in the interface domain of the Aβ(1–42):CaM complex, for example, Met71, Met51, Met36, and Met72 [60]. This location makes these methionines highly prone to oxidation, as the redox cycling of iron bound to Aβ is a source of reactive oxygen species [14, 20]. Oxidation of CaM’s methionines has been shown to impair the activity of CaMBPs [62]. However, to the best of my knowledge, the extent of the oxidation of CaM’s methionines in the AβO-induced dysregulation of CaMBPs remains to be experimentally studied.

Fradinger et al. [63] have shown that COOH-terminus peptides of Aβ(1–42) assemble into Aβ(1–42) oligomers, disrupt oligomer formation, and protect neurons against Aβ(1–42)-induced neurotoxicity. These and other investigators have concluded that the COOH-terminus plays a major role in the formation of Aβ(1–42) oligomers [63, 64]. Also, Fradinger et al. [63] showed that Aβ(31–42) is the most potent inhibitor of Aβ(1–42)-induced neurotoxicity. Other results that highlight the relevance of the hydrophobic amino acid residues close to the COOH-terminus domain in the neurotoxicity of Aβ peptides are that 1 μM of Aβ(25–35) has the same early neurotrophic and late neurotoxic activities as 1 μM of Aβ(1–40), while up to 20 μM Aβ(1–16) and Aβ(17–28) did not show trophic or toxic activity [65]. Moreover, Andreetto et al. [66] concluded from the results obtained using membrane-bound peptide arrays and fluorescence titration assays that the amino acid residues 27–32 and 35–40 of Aβ(1–40) are part of the interacting domain leading to Aβ(1–40):Aβ(1–40) self-association. As the neurofibrillary tangles are a well-established histopathological hallmark of AD, it is to be recalled here that the Aβ COOH-terminus binds to multiple tau domains and subsequently forms soluble Aβ-tau complexes in vitro [5].

Noteworthy, the hydrophobic peptide VFAFAMAFML (amidated-C-terminus amino acid), designed to bind to the Aβ(1–42) amino acid residues of the COOH-terminus domain strongly interacting with CaM [60], is a potent inhibitor of the formation of Aβ(1–42):CaM and of Aβ(1–42):calbindin-D28k complexes. Of value for its potential therapeutic use is that the incubation of HT-22 cells in culture for 24 h with up to 1 micromolar concentration of VFAFAMAFML does not have any significant effect on cell viability, while sub-micromolar concentrations of this peptide efficiently antagonizes Aβ(1–42) complexation with CaM and calbindin-D28k [60]. Many alternate sequences of highly hydrophobic amino acids share similar hydrophobicity plots and, also, fit the geometrical constraints of the 3D structure of the 29–42 segment of Aβ(1–42) [67]. However, it must be noted that highly hydrophobic sequences of 8–10 amino acids are buried within the inner core of proteins. Therefore, these will be accessible to intracellular Aβ only after an extensive intracellular protein degradation up to peptides of 8–10 amino acid residues. Only the ubiquitin-proteasome system, an intracellular system that functions to maintain intracellular proteostasis, fulfills these requirements. Indeed, most of the antigenic peptides of 8–10 amino acids presented by the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules are produced by the proteasome [68, 69], and many of them display a hydrophobicity quite like the above mentioned Aβ(1–42) antagonist peptide.

Finally, it is worth noting here that peptides able to antagonize the binding of extracellular Aβ(1–42) and Aβ(1–40) to proteins involved in their uptake by neurons, like apoE and RAGE, have been shown to ameliorate Aβ peptide-mediated neuronal disorder [70–73].

The endogenous neuropeptides that can afford neuroprotection against the toxic actions of Aβ on neurons through binding to Aβ hydrophobic domains are called here Aβ-antagonist hydrophobic neuropeptides, as in [67]. As will be briefly analyzed in this section, many studies have reported the occurrence of significant alterations in the levels of these types of neuropeptides and/or of their receptors in the brain of AD patients in relation to healthy brains of age-matched individuals.

It must be noted that the proteasome activity in the AD brain is lower than in age-matched healthy brains [74, 75]. Therefore, the production of hydrophobic peptides of 8–10 amino acid residues declines in the AD brain. As these peptides are endogenous Aβ-antagonists, it follows that the AD brain is more prone than a healthy brain to Aβ-induced neurodegeneration. In addition, the proteasome is the major source of hydrophobic antigenic peptides needed to maintain the normal activity of MHC class I molecules [76], and since Aβ(1–42) is not a good substrate for cytosolic endopeptidases it may serve as a “chaperone” for these antigenic peptides [68]. Thus, this “chaperone-like” role of Aβ(1–42) may impair the functional activity of MHC class I molecules in the AD brain, a hypothesis that, due to its potential relevance, deserves to be experimentally assessed.

Substance P [77, 78], islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP) [79, 80], somatostatin [81, 82], chromogranin A and B-derived peptides [83, 84] and cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript encoded peptides [85] are other Aβ-antagonist hydrophobic neuropeptides that have been reported to co-localize with Aβ plaques in brain areas of AD patients.

Substance P was one of the firstly identified Aβ-antagonist hydrophobic neuropeptides. Yankner et al. [65] noticed that there is a high homology between the amino acid sequences of tachykinin peptides and that of Aβ(25–35), and reported that sub-micromolar concentrations of substance P, a tachykinin neuropeptide, inhibit the neurotoxic effects of Aβ(1–40) in hippocampal neurons. The findings that substance P level decreases in cortex, hippocampus, and dentate gyrus of AD patients [86, 87], lend further support to a protective role of substance P against Aβ neurotoxic effects in vivo.

The interaction of intrinsically disordered IAPP with Aβ(1–42) and Aβ(1–40) has been extensively studied, and the amino acid residues of Aβ involved in the formation of the complex Aβ:IAPP have been identified, see [66, 88, 89]. Andreetto et al. [66] concluded that Aβ(29–40) and Aβ(25–35) are the amino acid residues of Aβ peptides acting as the stronger ligands for IAPP. As IAPP is associated with type 2 diabetes, this interaction bears a special biomedical relevance, because epidemiological and pathophysiological evidence point out that the AD and type 2 diabetes are linked diseases [79, 80].

Somatostatin, a small cyclic neuropeptide, is an Aβ-antagonist hydrophobic peptide selectively enriched in human frontal lobes [81, 82]. The levels of somatostatin in the cerebral cortex decline during aging and this decline is more pronounced in AD [90]. In addition, it has been proposed that this decline in somatostatin levels could produce a reduced clearance of Aβ, because somatostatin has been shown to induce the release of Aβ degrading enzymes [91]. Regarding chromogranin A and B-derived peptides, it should be noted that their levels in the cerebrospinal fluid of AD patients have been reported to be altered relative to those found in age-matched controls [92].

Finally, the mitochondrial-derived peptide humanin merits a brief comment, because mitochondrial dysfunction has been associated with AD-induced brain neurodegeneration, see, e.g., [93]. Humanin seems to be a good candidate for Aβ-antagonist hydrophobic neuropeptide, because it has been reported that humanin interacts with Aβ oligomers and counteracts Aβ in vivo toxicity [94].

It must be noted that the relative efficiency of the hydrophobic neuropeptide listed above as Aβ-antagonists in early or late stages of AD depends on their dissociation constants from Aβ monomers or oligomers, which is not known at present for all of them. Also, the identification of the amino acid residues of Aβ in the interacting domain with many of these neuropeptides is still poorly defined.

During last few years, global neuropeptidome analyses have pointed out that there are significant variations in the levels of brain neuropeptides between AD patients and age-matched individuals. Interindividual variation in the level of hydrophobic endogenous neuropeptides that bind to the COOH-terminus of Aβ monomers/oligomers is likely to affect the onset of sporadic AD, and, also, the rate of brain damage progression in this disease. Therefore, these endogenous brain neuropeptides may become helpful biomarkers in the evaluation of the risk of the onset of sporadic AD and/or for the prognosis of AD.

In addition, several Aβ-antagonist hydrophobic peptides that bind to the COOH-terminus of Aβ seem, a priori, candidates to become targets for the development of novel therapies against Aβ-induced neurodegenerative diseases. It is important to recall here that the amino acid residues 24–42 of the COOH-terminus domain of Aβ(1–42) play the leading role in the interaction of Aβ(1–42) with the intracellular proteins displaying high affinity for AβO analyzed in this review. As briefly commented in the Introduction, extracellular AβO internalization plays a critical role in Aβ neurotoxicity. Three proteins that bind extracellular AβO with high affinity have been proposed to play an active role in the internalization of extracellular Aβ, namely, apoE4, α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor, and RAGE [31]. Interestingly, the interacting domain of Aβ(1–42) with these proteins comprises amino acid residues 12–28 for apoE4 [95, 96] and α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor [97], and 17–23 for RAGE [98]. Therefore, it can be foreseen that peptides binding to amino acid residues 12–28 may act synergically with those binding to the 24–42 COOH-terminus of Aβ(1–42) to antagonize Aβ neurotoxicity interfering with Aβ internalization and intracellular Aβ-induced toxic actions, respectively.

Although the efficient delivery of peptides into the brain is still a cumbersome technical issue under active research, recently developed nanocarrier particles show promising advances for the transport across the blood-brain barrier of short peptides directed to brain structures, reviewed in [99]. In addition, considering that AD is a multifactorial disease, a priori, Aβ-antagonist hydrophobic peptide-based therapy could be used in combination with other currently used therapies.

This review is focused on hydrophobic peptides that have been shown to be antagonists of neurotoxic Aβ forms based on studies performed in vitro, ex-vivo with cellular cultures, and in vivo with animal models of AD. Two major conclusions can be reached from these studies: (1) measurements of the brain levels of hydrophobic endogenous neuropeptides that bind to the COOH-terminus domain of Aβ monomers/oligomers may serve as a complementary tool for the prognosis of the onset and course of AD; (2) Aβ-antagonist hydrophobic peptides that bind to the COOH-terminus domain of Aβ provide insights for the development of novel drugs of use in therapeutic treatments against Aβ-induced neurodegenerative diseases. Although these conclusions open new perspectives for the clinical management of AD, further studies are needed to overcome the current limitations for the translational application of these findings. The protection against the loss of the proteasome activity in AD brain, which plays a major role in the production of this type of hydrophobic peptides in the brain, is yet a challenging scientific issue and pharmacological treatments to stimulate the brain proteasome activity are yet to be established. In addition, despite that studies performed with brains of AD patients show that several endogenous hydrophobic neuropeptides co-localize with Aβ plaques, it must be noted that specific radiochemical tracers will be needed for the use of neuroimaging tools to monitor regional brain changes of these endogenous neuropeptides during AD progression at the early stages of the disease. Finally, for synthetic peptides, further experimental studies with synthetic peptides in animal models of AD are needed before their use in clinical trials, like development of nanoparticles for their efficient transport across the blood-brain barrier, pharmacological, toxicological, and pharmacokinetic studies.

AD: Alzheimer’s disease

apoE4: apolipoprotein E4

APP: amyloid precursor protein

Aβ: amyloid β

AβOs: amyloid β oligomers

BACE1: β-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1

CaM: calmodulin

CaMBPs: calmodulin binding proteins

IAPP: islet amyloid polypeptide

MHC: major histocompatibility complex

RAGE: receptor and receptor for advanced glycation end products

CGM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing.

The author declares that he has no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Janusz Wiesław Błaszczyk

Tatsushi Yuri ... Hisashi Nojima

Priyanka Sengupta ... Debashis Mukhopadhyay

Danqing Xiao, Chen Zhang

Julius Mulumba ... Yong Yang

Felipe P. Perez ... Maher Rizkalla

Ezra C. Holston

Jorge Medeiros

Ryszard Pluta