Abstract

The SAR-CoV-2 virus has evolved to co-exist with human hosts, albeit at a substantial energetic cost resulting in post-infection neurological manifestations [Neuro-post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC)] that significantly impact public health and economic productivity on a global scale. One of the main molecular mechanisms responsible for the development of Neuro-PASC, in individuals of all ages, is the formation and inadequate proteolysis/clearance of phase-separated amyloid crystalline aggregates—a hallmark feature of aging-related neurodegenerative disorders. Amyloidogenesis during viral infection and persistence is a natural, inevitable, protective defense response that is exacerbated by SARS-CoV-2. Acting as chemical catalyst, SARS-CoV-2 accelerates hydrophobic collapse and the heterogeneous nucleation of amorphous amyloids into stable β-sheet aggregates. The clearance of amyloid aggregates is most effective during slow wave sleep, when high levels of adenosine triphosphate (ATP)—a biphasic modulator of biomolecular condensates—and melatonin are available to solubilize amyloid aggregates for removal. The dysregulation of mitochondrial dynamics by SARS-CoV-2, in particular fusion and fission homeostasis, impairs the proper formation of distinct mitochondrial subpopulations that can remedy challenges created by the diversion of substrates away from oxidative phosphorylation towards glycolysis to support viral replication and maintenance. The subsequent reduction of ATP and inhibition of melatonin synthesis during slow wave sleep results in incomplete brain clearance of amyloid aggregates, leading to the development of neurological manifestations commonly associated with age-related neurodegenerative disorders. Exogenous melatonin not only prevents mitochondrial dysfunction but also elevates ATP production, effectively augmenting the solubilizing effect of the adenosine moiety to ensure the timely, optimal disaggregation and clearance of pathogenic amyloid aggregates in the prevention and attenuation of Neuro-PASC.

Keywords

Adenosine moiety effect, adenosine triphosphate (ATP), mitochondrial dynamics, glymphatic system, neurodegenerative disorders, protein hydration, slow wave sleep, viral persistenceIntroduction

Neuro-PASC: symptoms, challenges, and solutions for viral persistence in the brain

The classification of Neuro-post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC) describes a wide range of neurological manifestations observed in individuals with PASC, or “long COVID” [1]. Cognitive impairment including brain fog and frontal network dysfunctions involving deficits in attention, memory, and executive function, can persist beyond one year in recovered individuals regardless of infection severity or hospitalization status [2–11]. Optical clearing and imaging studies observed the persistent presence and accumulation of the SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) and nucleocapsid (N) proteins at the skull-meninges-brain axis of postmortem skulls from patients who died from COVID-19. Whereas the S protein from SARS-CoV-2 was detected in 10 out of 34 postmortem skull samples obtained from patients who did not die of COVID-19 causes. The fact that skull marrow cells, meningeal cells, and brain tissue cells all tested positive for the S protein at rates of 2.3%, 2.8%, and 1%, respectively, implies that viral persistence is maintained in many individuals long after the clearance and resolution of infection. Similarly, healthy mice aerosol-inoculated with SARS-CoV-2 (Omicron B, XBB sub-lineage) virus exhibited clear persistence of the S protein in the head at 28 days post-infection after full recovery from acute symptoms and viral clearance from the skull marrow and brain cortex [12].

A prospective longitudinal cohort study of 475 adults (mean age 58.26 years) hospitalized with a clinical diagnosis of COVID-19 in the UK reported that participants experienced not only the emergence of new psychiatric and cognitive symptoms over the first 2–3 years but also the continued deterioration of existing symptoms present at 6 months post-hospitalization [13]. In 2023, an ambispective cohort study evaluated post-hospitalization Neuro-PASC (PNP, n = 50) and non-hospitalized Neuro-PASC (NNP, n = 50) patients in Medellin, Columbia diagnosed with COVID-19 between 2020 and 2023. The analysis of the data collected revealed that 64% of PNP, compared to 42% of NNP presented abnormal neurological symptoms that included brain fog (60%) and myalgia (42%). While numbness/tingling and abnormal body sensations were more prevalent in PNP (58% and 42%, respectively) than in NNP (24% and 12%, respectively). Conversely, brain fog was more common in NNP (64%) than PNP (56%). Both groups presented identical levels of fatigue (74%) and sleep dysregulation (46%) during examinations [14]. In November 2024, a large cross-sectional study involving 200 PNP and 1100 NNP patients reported that younger (18–44 years) and middle-aged (45–64 years) subjects, regardless of infection severity, were disproportionately affected by neurological symptoms compared to older (65+ years) subjects [15].

The potential mechanisms responsible for neurological and even structural alterations of the brain by the SARS-CoV-2 virus [16–21], remain to be fully elucidated. Nonetheless, an exhaustive list of reviews, hypotheses, and experimental work examining mechanisms including, but not limited to, neuroinflammation [22–25], mitochondrial quality control [26, 27], mitochondrial DNA content [28, 29], and endoplasmic reticulum stress [30] have been presented as causes responsible for the activation of Neuro-PASC [31–37]. Overwhelming evidence supports the existence of a strong, positive correlation between SARS-CoV-2 infection and neurological dysfunction [38–43]. A systematic analysis of resting-state electroencephalogram (rsEEG) in Long COVID patients revealed striking abnormalities resembling those exhibited in early developmental stages of neurodegenerative diseases (NDDs) including Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and related dementia (ADRD). The shift to lower frequencies in the rsEEG (reduced alpha rhythm, increased slow waves) and epileptiform-like EEG signals imply potential overlapping pathophysiology in both Neuro-PASC and ADRD [44]. Although a systematic review comprising 18 studies involving 412957 COVID-19 patients aged ≥ 65 years reported the identification of new-onset cognitive impairment in 64% of the patients [45], viral infection-induced cognitive impairment may not be unique to the SARS-CoV-2 virus, as recent advances link viral amyloidogenesis to neurodegeneration [46].

A dominant association exists between viral infections and NDDs

Many viral infections are associated with elevated risks in the development of NDD. A thorough data analysis of cohorts (> 800000) in the FinnGen and the UK Biobank was conducted to identify longitudinal and cross-sectional associations between viral exposures and common NDDs including AD, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), dementia, Parkinson’s disease (PD), and multiple sclerosis (MS). The study reported 45 viruses, including viral encephalitis, viral hepatitis, influenza, pneumonia, herpes simplex, and varicella-zoster virus are associated with an elevated risk of NDD up to 15 years post-infection [47]. An analysis of transcriptomic and interactomic profiles of brain samples from the Gene Expression Omnibus repository of AD patients who died of COVID-19, AD without COVID-19, COVID-19 without AD, and control individuals found 21 interactome key nodes are dysregulated in AD patients who died of COVID-19, with the implication that SARS-CoV-2 infection exacerbated the AD condition due to the presence of higher levels of amyloid-beta (Aβ), inflammation, and oxidative stress [48]. Whether the SARS-CoV-2 virus features characteristics distinct from other viruses and exacerbates NDD is unclear and requires elucidation.

The development of Neuro-PASC is not specific to age or infection severity

Although age-related hippocampal atrophy and neuroinflammation can augment cognitive impairment [49], the development of Neuro-PASC is observed across all ages and health groups. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 11 studies involving > 6.8 million controls and 0.94 million infected subjects reported a higher risk in the development of new-onset dementia in adults aged > 60 years at different intervals post COVID-19 diagnosis [50]. Whereas, a longitudinal multimodal MRI study in Lombardy Italy, investigating the neural activities in mildly-infected, healthy young adults (mean age 24 years) 12 months post-infection, discovered persistent structural and functional changes in specific brain areas resulting in deficits in olfaction, visual/verbal domain of short-term memory, and reduction in spatial working memory compared to uninfected controls [51]. Imaging evidence from ultra-high field 7 T MRI of COVID-19 survivors (median time of 6.5 months post-hospitalization), showed magnetic resonance susceptibility abnormalities at multiple regions of the brainstem, including the medulla oblongata, pons, and midbrain [52].

A registered clinical trial (NCT04865237), conducted in the United Kingdom between March 2021 and July 2022, examined the changes in cognitive functions in 34 healthy, seronegative young adults aged 18–30 years, inoculated with Wildtype SARS-CoV-2. The study reported that subjects with mild infections exhibited statistically lower cognitive scores that persist for one year or longer, compared to uninfected test subjects [53]. SARS-CoV-2 intranasally inoculated ferrets demonstrated subclinical to mild respiratory disease. Even though there is no evidence of brain infection detected via in situ hybridization or immunohistochemistry, the presence of viral RNA in the brain, 7 days post infection, induced neurovirulence associated with microglial activation, astrocytic deactivation, and Alzheimer type II astrocytes [54]. Additionally, the discovery of substantial abnormal neuroimaging findings in a significant number of young children with neurological symptoms post COVID-19 infection [55] all point to the potential involvement of multifaceted, universal molecular mechanisms associated with phase separation and amyloidogenesis in the development of Neuro-PASC that may affect infected/exposed subjects of all ages and health conditions.

Melatonin as a cost-effective, time-tested solution for the potential treatment of Neuro-PASC

Melatonin (N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine) is an evolutionarily conserved molecule [56] that can effectively counter the development of Neuro-PASC by rebalancing the complex energetic scales of amyloidogenesis promoted by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The impressive, extensive array of functions and features associated with melatonin since its isolation and identification in bovine pineal tissues in 1958 [57] provide convincing rationale for the ubiquitous presence of this ancient molecule, synthesized in all tested eukarya, bacteria, and archaea [58–60]. Nevertheless, proposals presenting melatonin as an effective regulator of phase separation under various contexts including neurodegenerative disorders [61], cancer multidrug resistance [62], viral phase separation [63], dementia [64], cataractogenesis [65], and mitochondrial function [66], offer a novel perspective in the investigation of the underexplored, expansive functions of the indoleamine for more than 2 billion years in Archaea and Bacteria prior to the advent of Eukarya [66].

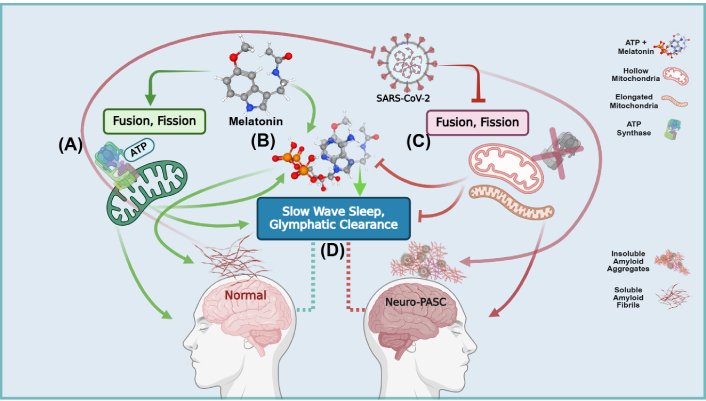

The first report of intracellular amyloids detected in the domain of Archaea stratifies an additional layer of significance in the synergy between melatonin and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) in the regulation of phase separation and amyloidogenesis that began close to 4 billion years ago (Ga). This review will apply current knowledge to explore potential molecular mechanisms employed by melatonin in synergy with ATP for the regulation of phase separation that can modulate pathological amyloidogenesis promoted by SARS-CoV-2 in Neuro-PASC (Figure 1).

Schematic overview of the synergistic regulation of amyloid solubilization and clearance during slow wave sleep in Neuro-post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC). (A) During viral infection/persistence, exogenous melatonin enhances the production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and synthesis of mitochondrial melatonin, preventing SARS-CoV-2 inhibition of mitochondrial bioenergetics and dynamics; (B) melatonin augments the adenosine moiety effect that promotes the solubilizing effect of ATP to regulate protein phase transitions during aggregation. The hydrating effect of melatonin—facilitated by the indole π clouds and hydrogen bonding with water molecules—combined with ATP, prevents hydrophobic collapse and delays the transitioning into β-sheets during protein folding; (C) the SARS-CoV-2 virus and its structural, non-structural, and accessory proteins facilitate and accelerate the nucleation of physiological amyloid fibrils that have additional antimicrobial protective function into pathological amyloid aggregates. The SARS-CoV-2 virus further exacerbates the accumulation of insoluble amyloid aggregates by diverting nutrients away from mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) ATP production into anabolic glycolytic pathways that support viral replication and maintenance. The suppression of fusion and fission creates dysfunctional hollow mitochondria devoid of the ATP synthase and elongated mitochondria. Unable to differentiate into functional subpopulations under nutrient deficiency, mitochondrial dysfunction further elevates imbalances between energy production and the synthesis of macromolecular precursors; (D) the optimal clearance of soluble amyloids during slow wave sleep by the glymphatic system must be supported by the adequate presence of both melatonin and ATP. The SARS-CoV-2 virus during infection and persistence prevents the effective brain clearance of excess insoluble amyloid aggregates due to deficient ATP and melatonin as a result of mitochondrial dysfunction. Created in BioRender. Loh, D. (2025) https://BioRender.com/b31s634

Amyloids, phase separation, and SARS-CoV-2: the perfect storm for Neuro-PASC

The ~4 Ga relationship between amyloids, phase separation, and viruses

Since its first proposal in 1991 [67], the amyloid hypothesis remains controversial. Notwithstanding the copious experimental evidence correlating the formation of Aβ with cytotoxic effects that may advance the development of NDDs [68–71], the detection of Aβ in cognitively normal individuals presents unresolved questions on the nature and function of Aβ oligomeric assemblies that inevitably increase with the aging process [72–77]. Recent advances in the antimicrobial functions of Aβ that may protect the brain against viral infections begin to reveal the multilayered complexity of amyloidogenesis [78]. Bacteria including Escherichia coli produce protective biofilms strengthened by amyloid fibrils known as curli [79]. Yet curli formation triggers the enhanced production of cytotoxic host Aβ oligomers that suppressed curli synthesis and inhibited E. coli biofilm density and elevated susceptibility to gentamicin antibiotic treatment [80]. The results of this explicit experiment open an unexpected door revealing the ancient, complex roles of amyloids in all three major domains of life where the neurodegenerative effects of aberrant Aβ aggregation may be the result of protective antimicrobial activity [81]. Furthermore, amyloids confer advantageous adaptive fitness via the inheritance of proteinaceous epigenetic memory [82].

The discovery of amyloid-forming, prion-like domains in Archaea consolidates their functional, physiological existence not only in all three major domains of life but also in the last universal common ancestor (LUCA) [83, 84]. Accordingly, amyloids may have played a major role in the origin of life, increasing the stability of RNA in extreme, fluctuating environments by acting as templates and catalysis for chemical reactions that favor replication [85]. While the exact origin of viruses remains enigmatic [86], and the debate on whether giant viruses constitute the fourth domain of life continues [87], the early cellular origin of viruses sharing a common evolutionary path with Archaea and Bacteria since their inception is, nonetheless, supported by phylogenomic data [88] as well as direct and indirect inferences from paleovirology [89]. All evidence examined to date appears to suggest that viruses are ancient and may even predate LUCA [90–92]. Upon invasion by viruses, ancient unicellular living organisms, especially archaea, inevitably formed cytotoxic amyloids as their only course of effective protection [46, 93–95].

Due to the nature of viral replication that is dependent upon phase separation, viral invasions of early organisms can readily transform functional proteins in their soluble monomeric states into insoluble, crystalline, Aβ-sheet assemblies [96]. Viruses facilitate the heterogeneous nucleation and phase transition of amyloids via direct physicochemical mechanisms that act as catalysts, promoting and accelerating the assembly of Aβ-sheets [97, 98]. Despite being potentially protective in nature, the cytotoxicity of amyloid oligomers is a conundrum requiring reconciliation and clarification [99–102].

Phase-separated biomolecular condensates promote amyloidogenesis

Phase separation is an intrinsic feature of nature used by all tested living organisms in the three major domains of life to organize and sustain fundamental biological processes. Spontaneous, nonequilibrium thermodynamic conditions governing the competition between entropy and enthalpy, drive intracellular phase separation in the assembly of membraneless organelles, also known as biomolecular condensates (BCs) [103–105]. BCs are dynamic, micron-scale, fluid compartments that can rapidly organize/reorganize cellular biochemistry to accelerate, slow, promote, or inhibit cellular functions and reactions, by either increasing, decreasing, including, or excluding reactants, enzymes, and substrates according to the fluctuating requirements of the cell [106]. Recent advances link the formation of amyloid fibrils to phase separation of condensates [107], where the interface of condensates promotes the accelerated formation of amyloid fibrils [108]. Viruses employ molecular sorting driven by phase separation and the exploitation of the host phase separation machinery to enable viral replication and persistence [63, 109–113]. Fluctuations in the energy landscape of aggregation pathways occurring at BC interfaces can subsequently become active sites for the heterogeneous nucleation of pathological amyloid fibrils promoted by viral phase separation [114–116].

BCs have been observed to both promote and inhibit the self-assembly of fibrillar proteins [117–120], which is a process commonly associated with NDDs including AD, PD, as well as prion diseases. The self-assembly of functional amyloids, dependent upon intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs), may have played decisive roles in the origin of life and the evolution of species [121–123]. The formation of amyloid fibrils rich in insoluble β-sheets networks, stabilized by hydrogen (H) bonds acting as chemical adhesives [124], is intrinsically a phase transition of proteins from an amorphous liquid state into a solid, insoluble state via phase separation, nucleation, and growth processes [125–127]. The addition of phase-separated BCs near natively folded protein assemblies can trigger the abrupt acceleration of protein aggregation in the self-assembly of amyloid aggregates [117, 128]. Nevertheless, protein folding—whether self-assembling into stable, highly-ordered, β-sheets or physiological, well-defined, functional structures—is a common feature exhibited by, potentially, all polypeptide sequences, regardless of their native states or localization [129–133]. Perturbation in the energy landscape can directly affect the outcome of protein folding and aggregation. The transitioning into β-sheets during protein folding involves hydrophobic collapse, formation of H-bonds, and intermolecular electrostatic interactions that lower the Gibbs free energy but increase solvent entropy [134, 135].

SARS-CoV-2 escalates the self-assembly of crystalline Aβ-sheets

Viruses can accelerate the phase transition of amorphous amyloids into stable β-sheet aggregates. Acting as chemical catalysts, viruses modulate hydrophobic collapse and the nucleation/condensation of proteins, potentially by altering the activation barrier (ΔG#) for protein folding via a wide array of molecular mechanisms—including phase separation—that will be addressed, as allowed by scope, in this review [97, 98, 134]. Accordingly, abundant in vitro studies report that different structural, non-structural, and accessory proteins of the SAR-CoV-2 virus from wildtype and prominent variants readily form amyloid aggregates that are commonly associated with NDDs. Even SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acids that have been deactivated by UV radiation are able to induce amyloid aggregation in vitro, by directly acting as physicochemical mechanistic catalysts that promote amyloid aggregation via heterogeneous nucleation and phase transition that do not involve templating. The aggregation of disease-associated proteins is often seeded by BCs containing proteins with unfavorable molecular interactions [117]. The enhanced cytotoxicity of ground-state amyloid crystals assembled from SARS-CoV-2 accessory open reading frame 6 (ORF6) protein can increase the level of neuronal apoptosis compared to higher free energy, non-crystalline amyloid assemblies [136–153]. Please see Table 1 for individual study descriptions and corresponding observed effects. The formation of β-sheet aggregates as a result of viral infection is possibly an evolutionarily conserved response in eukaryotes and archaea. As such, it is not unreasonable to expect living organisms to be able to effectively manage the cytotoxic effects via the maintenance of proteostasis.

SARS-CoV-2 accelerates and exacerbates host amyloidogenesis

| SARS-CoV-2 amyloidogenic components | Study type | Observed effects | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spike 1058 fragment (1058HGVVFLHVTYV1068) | All-atom discrete molecular dynamics (DMD) simulations | Spike 1058 accelerated amyloid-beta (Aβ)42 cytotoxicity, aggregation, and fibrillization in vitro | [136] |

| Spike532 (532NLVKNKCVNFNFNGLTGTGV551)Spike601 (601GTNTSNQVAVLYQDVNCTEV620) | In vitro conversion assay | Spike532 and 601 selectively seed and accelerate amyloid fibril formation of human prion protein and Aβ1–42, respectively | [137] |

| Synthetic spike (S) protein peptides | In vitro | Endoproteolysis of S protein by the neutrophil elastase protease produced amyloidogenic peptides. Whereas full-length folded S-protein did not form amyloid fibrils | [138] |

| S protein receptor binding domain (RBD) of the Alpha and Omicron variants | Molecular dynamics simulation | Aβ42 amyloid fibrils can bind to the RBDs of the S proteins and diffusively slide on the RBD surfaces | [139] |

| S RBD of the Delta Plus and Omicron variants | In vitro, in silico/experimental analysis | The RBD self-assembles into aggregates with 48.4% β-sheet content. The Omicron variety displays higher amyloidogenic potential due to distinct mutations in the RBD regions | [140] |

| S protein 1 (S1) | In vivo male Sprague-Dawley rat (6 weeks old) model | In the rat brain, a single intranasal dose of S1 (0.5 μg/10 μL) doubled the aggregation of α-synuclein (α-syn) relative to controls | [141] |

| Recombinant SARS-CoV-2 S1, S2, RBD, and nucleocapsid (N) proteins (NCAPs) | In vitro, Escherichia coli, human embryonic kidney (HEK) Expi293F cell line, and other eukaryotic cell cultures | Recombinant S1, S2, RBD, and NCAPs spontaneously self-assemble into nanoparticles/nanofibers forming amyloid-like structures in tested cell lines | [142] |

| S proteins and NCAPs | In vitro HEK293 cells, bioinformatics analysis | S proteins and NCAPs displayed high binding affinity with α-syn. The direct interactions elevated α-syn expression and accelerated aggregation, forming Lewy-like bodies in HEK293 cells | [143] |

| NCAP low complexity domain (LCD) | In vitro | The LCD of NCAP phase separates and forms amyloid-like structures in the presence of RNA | [144] |

| NCAP, S protein | In vitro, neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells | NCAP accelerated the aggregation of α-syn into amyloid fibrils via nucleation of multiple protein complexes. Whereas S protein had no effect on α-syn aggregation | [145] |

| Envelope (E) protein C-terminus-derived 54SFYVYSRVK62 (SK9) peptide | In vitro | SK9 not only self-assembles into amyloid fibrils, but also binds to amyloidogenic hotspots in lipid-free serum amyloid A (SAA), promoting SAA fibrillization | [146] |

| E protein SK9 peptide (C-terminus) | Molecular dynamics simulation | The binding of SK9 to SAA promotes amyloidosis by increasing the frequency and stability of amyloid fibrils to favor β-strand formation | [147] |

| Open reading frame 6 (ORF6) | High-speed atomic force microscopy visualization | ORF6 amyloidogenic peptides spontaneously self-assemble into amyloid protofilaments | [148] |

| ORF 6, ORF10 | In vitro, atomic force microscopy, transmission electron microscopy, amyloid prediction algorithms | ORF6 and ORF10 peptide sequences self-assemble into ground state amyloid crystals markedly elevated the rate of apoptosis at low concentrations in a human-derived neuroblastoma cell line (SH-SY5Y) | [149] |

| S protein fusion peptide 1, 2, ORF10, non-structural protein 6 (NSP6), NSP11 | In vitro aggregation study | All structural, accessory, and NSPs studied form amyloid aggregates with high propensity under near-physiological in vitro conditions | [150] |

| NSP3 | Transgenic Alzheimer’s disease (AD) Drosophila melanogaster eye model [glass multiple repeats (GMR) > Aβ42] | NSP3 misexpression in AD fly eye worsens Aβ42-mediated neurodegeneration, increases apoptotic cell death and ROS | [151] |

| UV-inactivated SARS-CoV-2 virus | Ex vivo, healthy human cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) | UV-inactivated nucleic acids act as catalysts promoting amyloid aggregation and markedly depleting soluble proteins in human CSF compared to controls | [152] |

| SARS-CoV-2 S protein | Transnasal infection of 18hACE2 mice | Increased accumulation of phosphorylated tau protein and activation of glycogen synthase kinase 3β in the ventral tegmental region induced neuronal cell death | [153] |

It is almost implausible that an intrinsic, fundamental flaw in the design of the molecular chaperone disaggregase system is responsible for the increase in neurological dysfunctions associated with viral infections in humans, especially when considering the alarmingly high prevalence of Neuro-PASC in infected/exposed individuals. While the emergence of amyloids may have begun as early as LUCA [84], the existence of a proteostasis-defending heat shock response system that arose around the same time implies that this relationship is not only evolutionarily conserved but should also be robust and effective [154]. Yet this dynamic relationship is dependent upon an intricate balance between proteostasis and energy homeostasis [155]. Effective induction of stress-induced chaperones must be supported by the reduction of other housekeeping proteins to manage proteotoxic stress. Aberrant phase separation prevents the requisite assembly of molecular condensates that exert gain-of-function to amplify chaperone synthesis, and loss-of-function to repress expendable cellular functions. Thus, the ineffective shut-down of housekeeping processes during chaperone induction due to macromolecular assembly defects often results in less-than-optimal performance [156]. The successful assembly of BCs is ultimately determined by thermodynamic principles that govern phase separation, and the presence or absence of ATP.

Chaperones: the dilemma of energetic cost in amyloid disaggregation

Humans and mammals expend approximately 20% of resting energy in protein synthesis, while the cost for the degradation of damaged proteins is at least 20% of total energy expenditure [157, 158]. Thus, the destruction and resynthesis of proteins becomes an energetically costly expenditure. Consequently, the ability to salvage and reuse aggregated, unfolded/misfolded proteins and return them to their native folded states at a considerably lower energetic cost [159], allows stress-induced chaperone systems, including heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) [160, 161], to confer living organisms a unique survival advantage during evolution [157]. However, the degradation of mature amyloid fibrils by chaperones may involve trade-offs that are also dependent upon energetic costs. Amyloids were once believed to be indestructible under physiological conditions [162]. Recent advances reveal that the incomplete degradation of mature fibrils resulting in smaller fragments not only increases the cytotoxicity of the fragments over the original longer fibrils, but also seeds the production of additional amyloid aggregates [163–165]. Consequently, chaperone systems including HSP70 and its co-chaperone DNAJB1 [166] engage in “all-or-nothing” switch-like, tactical maneuvers—involving ATP-dependent unzipping and depolymerization—that can effectively target and disassemble short toxic oligomeric α-synuclein (α-syn) fibrils, but are unable to disassemble larger tau fibrils [167].

Ultimately, heat shock protein chaperone systems such as HSP70 achieve their molecular efficiency by consuming ATP energy [168]. Subsequently, the availability of ATP directly correlates with HSP70-mediated disaggregation of oligomeric fibrils [169, 170]. A lack of ATP can result in incomplete degradation, generating potentially toxic intermediate species that can seed additional fibril aggregation [163, 171]. While longer amyloid fibrils will require not only additional ATP but also increased copies of chaperones to achieve ideal chaperone-to-co-chaperone ratios that can efficiently bind and disassemble amyloid aggregates [172]. The increased metabolic cost of generating adequate copies of heat shock chaperones during stress is a considerable, limiting factor on the efficiency of chaperones in vivo. Molar ratios as high as 1:1 (HSP70:α-syn) were required in order to shift the immune landscape of rodent models from a proinflammatory one to an immunomodulatory phenotype [173]. Drosophila melanogaster larvae exposed to 36°C exhibited increased stress tolerance by elevating inducible heat-shock response expression of HSP70, albeit at a high energetic cost at the level of whole-organism metabolic rate. This increase in energetic cost associated with elevated gene expression may in turn impose limiting thresholds on the process itself in order to balance fitness against survival during evolution [174].

While it is unimaginable that the robust chaperone disaggregase system that evolved alongside amyloids since LUCA is incapable of fully disaggregating large amyloid fibrils resulting in proteostasis failure that causes neurological and other health impairments [175–177] under different contexts, especially during aging [178]; it is conceivable that nature never intended chaperones to assume the full responsibility of disaggregating large amyloid fibrils with their multifaceted, protective physiological functions, in addition to their Janus-faced cytotoxic effects. After all, the energy landscapes of protein folding and aggregation are diametrically opposed, competing mechanisms. As such, for chaperones to be able to both refold proteins and disaggregate amyloid fibrils may be a nonviable task. Molecular chaperones facilitate protein refolding into the native state by lowering the free-energy barrier while consuming ATP energy [135, 168]. Whereas, the assembly of aggregates associated with kinetically-trapped intermediates involve intermolecular reactions that drive the aggregates towards the thermodynamic ground state [135, 179]. Although seemingly impossible, living organisms have relied on melatonin, a simple, cost-effective solution to both prevent and disaggregate amyloid fibrils for billions of years.

Melatonin: an indispensable molecule in the glymphatic brain-cleaning system for amyloid aggregates

Cellular stress induces the expression of the HSP70 chaperone [180]. Stress can also modulate the thermodynamic energy landscape to promote phase-separated formation of amyloid fibrils and their subsequent aggregation [181]. Female Wistar Albino rats subjected to chronic stress of cerebral hypoperfusion but treated with 10 mg/kg melatonin via intraperitoneal (IP) injection for 14 days exhibited an impressive 5.94- and 6.05-fold reduction in the expression of HSP70 in their CA1 and CA3 hippocampal neurons, respectively, compared to hypoperfusion controls not treated with melatonin [182]. The fact that melatonin can suppress HSP70 while rescuing neurons from the damaging effect of hypoperfusion in a rodent model implies that melatonin may be highly effective at maintaining proteostasis during stressful conditions, albeit at a lower, more manageable energetic cost. Consequently, a deeper examination of the correlations between melatonin and the glymphatic system that is associated with the clearance and efflux of Aβ in rodents and humans is warranted.

The glymphatic system and the clearance of soluble amyloids in Neuro-PASC

In neurodegenerative disorders, proteostasis failure can be a vicious cycle where reduced protein degradation may be directly responsible for the ineffective clearance of amyloid aggregates [176, 183, 184]. Deficient proteostasis allows the transition of amyloid fibrils from soluble, amorphous states into insoluble, crystalline β-sheet aggregates [185], via breaching solubility limits coupled with a breakdown of supersaturation—promoted by defective clearance—where the solute concentration overwhelms its thermodynamic solubility [186]. Hence, maintaining the solubility of proteins could be one of the most important deciding factors that can ensure the effective clearance and efflux of amyloids from the brain via the glymphatic system to prevent amyloid crystallization [187]. Higher levels of soluble Aβ42 in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is associated with better neuropsychological function and increased volume in the hippocampus [188].

The efflux of soluble amyloid fibrils in the brain is facilitated by various clearance mechanisms including the blood brain barrier, blood-CSF barrier, the glymphatic drainage system, and intramural periarterial drainage [189]. Since the twin discoveries of meningeal lymphatics and the glial-lymphatic (glymphatic) system, increased understanding of how the movement of CSF is responsible not only for the delivery of nutrients but also for the clearance of brain waste [190, 191] begins to emerge. The dysfunction of the glymphatic system and meningeal lymphatics [192] is associated with defective clearance of metabolic waste in the CSF and the subsequent deposition of insoluble amyloid crystals resulting in the progression of NDDs [183, 193–196]. The discovery of the extension of the CSF flowing contiguously and continuously from the central nervous system to distal ends of peripheral nerves expands the potential reach and effect of the glymphatic system in the clearance of waste and the delivery of nutrients in health and disease [197]. However, the extent to which glymphatic-lymphatic brain clearance contributes to total brain clearance is currently unknown, and whether yet unidentified direct/indirect drainage routes exist, awaits elucidation [198, 199].

Sleep deprivation impairs glymphatic clearance of Aβ biomarkers

A novel, cross-sectional and longitudinal study, employing the analysis along the perivascular space (ALPS) index, investigated the relationship between whole-brain glymphatic activity and clinical/pathological features in participants with AD dementia (n = 47), mild cognitive impairment (n = 137), and healthy controls (n = 235). Although the ALPS index reflects only global glymphatic activity that may not identify regional glymphatic dysfunction, the results of the study revealed that glymphatic dysfunction precedes amyloid pathology including increased Aβ PET burden [200]. While Aβ42 in the CSF breaching the positive threshold often predicts brain atrophy and cognitive decline [201]. A multi-site randomized crossover clinical trial measured the changes in the plasma levels of Aβ42/Aβ40 and tau peptides from evening to morning in 39 healthy participants (between 50–65 years old) under in-laboratory conditions of both normal and deprived sleep conditions. Results of the study showed sleep-active elements—including higher EEG Delta power and lower brain parenchymal resistance—enhanced the overnight glymphatic clearance of amyloid aggregates; whereas sleep deprivation associated elements reduced the ability of the glymphatic system to clear Aβ biomarkers to plasma [202].

While the glymphatic system is only capable of removing soluble amyloid fibrils [203], the SARS-CoV-2 virus enhances the production of insoluble amyloid crystals, reducing soluble proteins [152] to severely compromise the cerebral efflux of Aβ via the glymphatic system. Consequently, dysfunction of the glymphatic system is often reported in recovered COVID-19 patients with only mild infections [204], but are associated with neurological impairments [205]. It is perhaps not a coincidence that the higher EEG Delta power that is correlated with higher overnight glymphatic clearance of amyloids is associated with deep, restorative, non-REM stage 3 slow wave sleep [206]. During slow wave sleep, melatonin is released from the pineal gland into the circulatory system, where maximum slow wave activity has been reported to coincide with melatonin secretion rhythm, with frequency band crests occurring before the rise of plasma melatonin concentrations [207]. Unexpectedly, fragmentation of stage 3 slow wave sleep in healthy male subjects was found to elevate morning melatonin in saliva by 1.8 times compared to controls [208]. Hypothetically, the increase in saliva melatonin may be associated with the activation of the serotonergic system during slow wave sleep suppression [209]. Alternatively, if melatonin is utilized for the glymphatic clearance of amyloids via solubilizing and preventing crystallization of amyloids, the observed 50% reduction of stage 3 slow wave sleep could severely inhibit glymphatic clearance during active sleep, resulting in higher levels of morning melatonin detected in the saliva as a result of unused melatonin during slow wave sleep glymphatic clearance. The subsequent increase in urinary melatonin excretion in cataract surgery subjects may be another example where the reduced utilization of melatonin for solubilizing and clearing cataractous amyloid aggregates in the crystalline lens via the ocular glymphatic system results in elevated circulatory/excretion melatonin levels [65, 210, 211].

Melatonin facilitates brain clearance of soluble amyloids in Neuro-PASC

Pineal melatonin is released directly into the CSF via the pineal recess of the third ventricle. Ventricular CSF melatonin measured in animals is at least one order of magnitude higher compared to levels detected in the blood of these animals. Whereas the ratio of pineal melatonin released into the CSF and the blood in humans still awaits quantification [212–215]. The indisputable correlation between sleep and the clearance of brain waste [216–218] suggests a definitive, protective role of melatonin in the brain during sleep [212, 219–221]. Postmortem ventricular CSF melatonin was conclusively demonstrated to be negatively correlated with the severity of AD pathology. Aged individuals with early neuropathological changes, including an accumulation of amyloid aggregates, exhibited a significant ~3.5- to ~7-fold decline in their CSF melatonin levels compared to individuals without any amyloid aggregates [222]. Similarly, a staggering 5-fold decline in ventricular postmortem CSF melatonin was identified in 85 AD patients compared to 82 age-matched controls without AD [223].

The adequate release of melatonin from the pineal gland into the CSF during slow wave sleep becomes an important consideration for the clearance of brain waste. An analysis of postmortem human brain material and melatonin levels in postmortem pineal glands obtained from AD subjects and healthy controls revealed that alterations in CSF melatonin levels closely mirrored the changes in the pineal melatonin content [224]. Young adult Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats, when subjected to both pinealectomy and intracerebroventricular (icv) Aβ1–42 infusion, experienced increased cognitive impairment and increased accumulation of Aβ1–42 and γ-secretase compared to pinealectomy-only and icvAβ1–42-only groups. However, 50 mg/kg melatonin supplementation via IP injection for 40 days improved all tested parameters in all groups to closely match control levels [225]. Accordingly, pineal gland dysfunction is believed to be responsible for many NDD-associated symptoms, and that the use of melatonin supplementation is an efficacious remedy for these conditions [226–229]. Importantly, pinealectomy experiments on animals revealed that the reduction in hippocampal melatonin levels is not only exaggerated by treatment with Aβ, but also induced learning and memory deficits [230, 231].

Accordingly, the dysregulation of melatonin from the fragmentation of NREM slow wave sleep resulting in increased amyloid aggregation and related symptoms are increasingly associated with proteostasis failure in neurodegenerative disorders [175, 232]. The insoluble amyloid crystalline assemblies induced by the SARS-CoV-2 virus not only present huge obstacles against clearance by the glymphatic system, but also accelerate and promote the self-assembly of additional insoluble Aβ-sheet-rich, inert, stable structures that encourage sequestration of proteins, promoting loss-of-function toxicity. The lower free energies and reinforced stability of these amyloid crystalline assemblies may be responsible for their increased cytotoxicity as a result of delayed/defective clearance, which is exacerbated by elevated depletion of soluble proteins by SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acids in human CSF compared to uninfected controls [149, 152, 233]. The Omicron variant was associated with sleep deterioration (new onset insomnia or exacerbation of chronic insomnia) together with altered brain structures in infected patients compared to healthy never-infected controls [234]. While asymmetric bilateral glymphatic dysfunction was reported in mild COVID-19 patients, where cognitive abnormalities were more evident in older patients and subjects identified with right-sided glymphatic dysfunction [204, 205].

Nonetheless, at the concentration of ~1.54 mM, melatonin administered for four weeks to chronic unpredictable mild stress (CUMS) mouse model of depression was able to restore glymphatic system function and improve sleep structure [235]. For close to three decades, a wealth of experimental in vivo and in vitro work studied the ability of melatonin to prevent amyloid fibrillization and disassemble amyloid aggregates in neurodegenerative disorders [225, 236–251]. Table 2 is a representative—but not comprehensive—collection, presented in chronological, descending order, of in vivo, ex vivo, and in vitro studies that examined the effects of melatonin on Aβ and phase-separated amyloidogenic aggregates under various contexts.

Melatonin supplementation inhibits amyloidogenesis and attenuates neurodegenerative disorders

| Melatonin dosage/duration | Study design | Results | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 50 mg/kg body weight (b.w.) via intraperitoneal (IP) injection for 40 days | Young adult male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rat Alzheimer’s disease (AD) model induced by intracerebroventricular (icv) infusion with amyloid-beta (Aβ)1–42 (100 μg) + pinealectomy | Melatonin treatment in icvAβ1–42 + pinealectomy rats, icvAβ1–42-, or pinealectomy-only rats significantly rescued impaired spatial memory and reduced accumulation of Aβ1–42 and γ-secretase | [225] |

| 20 mg/kg b.w. via oral route for 40 days | Male Wistar rat AD model, induced by icv streptozotocin (STZ) injection (3 nmg/kg b.w.) | Melatonin treatment improved cognitive performance of AD rats, reducing amyloid stimulation of microglia activation in hippocampal CA1 and CA3 regions | [236] |

| 10 mg/kg b.w. via IP njection for 30 days | Male Rattus norvegicus Wistar rat AD model, induced by icv-STZ injection (3 nmg/kg b.w.) | Melatonin reversed cognitive impairment in the spatial version Y-maze test and suppressed the accumulation of Aβ induced by icv-STZ injection | [237] |

| 0.5 mg per mouse per day in drinking water for 3 months | APP/PS1 (mutant APP and PS1 transgenic) AD and C57/BL6J mice as controls | Melatonin-treated transgenic mice, compared to controls, exhibited improved cognitive function and reduced deposition of Aβ plaques via suppression of NOD-like receptor family, pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome activation and increased transcription factor EB (TFEB) nuclear translocation | [238] |

| 100–5000 μM melatonin | In vitro study—aggregation/disaggregation of repeat domain tau (K18wt) performed in assays without adenosine triphosphate (ATP) | A dose-dependent disaggregation of preformed tau aggregates was observed: 14% with 100 μM, 54% with 5000 μM | [239] |

| 200–5000 μM melatonin | In vitro study—aggregation/disaggregation full-length tau (hTau40wt) by melatonin in Neuro2A cells | Tau treated with 200 μM melatonin showed no change in morphology compared to controls; 5000 μM melatonin treatment did not prevent aggregation but disaggregated tau fibrils into broken filaments | [240] |

| 0.3 mg per mouse in drinking water from day 7 after tauopathy induction to day 28 at termination | 4-month-old C57BL/6J mice injected with human tau mutation P301L (AAV-hTau) | Increased ROS and tau hyperphosphorylation starting at day 7 precedes cognitive decline; melatonin treated animals showed reduced memory impairment, tau hyperphosphorylation, ROS, and neuroinflammation | [241] |

| 10 μM/L melatonin | Ex vivo brain slices from human and 3-month-old SD rats exposed to okadaic acid (OA) to induce tau hyperphosphorylation | Melatonin reduced tau hyperphosphorylation and ROS to control levels in OA-treated human and rat brain slices | [241] |

| ~6 mg melatonin per mouse daily in drinking water starting at age 4 months until euthanasia | Transgenic Tg2576 AD mice, terminated at 4 months 1 week or 15.5 months | The brains of animals treated with melatonin terminated at 15.5 months exhibited impressive declines in oligomeric Aβ40/Aβ42 together with significantly increased lymphatic clearance of soluble monomeric Aβ40 and Aβ42 compared to untreated mice at the same age. Survival rates of melatonin-treated transgenic mice at 15.5 months were similar to wildtype controls | [242] |

| 10 mg/kg (IP) daily for 3 weeks | Male wild-type C57BL/6N mice (8 weeks old) injected with Aβ1–42 peptide | Melatonin treatment reversed Aβ1–42-induced synaptic disorder, memory deficit, and prevented Aβ1–42-induced apoptosis, neurodegeneration, and tau phosphorylation | [243] |

| 25 µM and 250 µM melatonin | In vitro α-synuclein (α-syn) peptide aggregation in primary neuronal cultures | Melatonin blocked α-syn fibril formation and destabilized preformed fibrils in a dose- and time-dependent manner; increased viability of primary mixed neurons treated with α-syn to ~97% in a time-dependent manner | [244] |

| Melatonin (50 mg/kg b.w.) IP injection for 5 days | Arctic mutation (E22G) male Swiss albino AD mice induced by Aβ1–42 synthetic peptides (scrambled and protofibrils) via icv injection | Melatonin treatment in Aβ protofibril-injected mice restored brain glucose levels to protect ATP production; inhibited ROS production and maintained homeostasis of antioxidant enzymes, intracellular calcium and acetylcholine levels in neuronal cells compared to controls and mice injected with scrambled AB1-42 peptides | [245] |

| 10 mg/kg (IP) × 5/day for 2 days, then × 2/day for 5 days | Arsenite-induced oxidative injury in substantial nigra of adult male SD rats | Reduced arsenite-induced α-syn aggregation, lipid peroxidation, and glutathione depletion | [246] |

| ~65 µg melatonin per mouse (2.6 mg/kg b.w.) in drinking water for 10 weeks, starting at age 14 months | Transgenic Tg2576 AD mice | Melatonin treatment failed to reduce brain Aβ levels or even oxidative damage | [247] |

| 40-ppm (w/w) in pelleted minimal basal diet (~5 mg/kg b.w.) for 11 weeks | Male B6C3F1 mice aged 6, 12, and 27 months | Significant reduction of Aβ in brain cortex tissues: 57% in Aβ40 and 73% in Aβ42; increased melatonin levels in cerebral cortex in all 3 treated age groups (12 > 6 > 27 months) compared to untreated | [248] |

| 6 mg melatonin per mouse daily in drinking water starting at age 4 months until euthanasia at 15.5 months | Transgenic Tg2576 AD mice | Increased survival in treated mice (3 deaths, 41 survivals) compared to untreated controls (13 deaths, 31 survivals) | [249] |

| 1.5 mg melatonin per mouse daily in drinking water starting at age 4 months | Transgenic Tg2576 AD mice | Striking reductions in Aβ levels in brain tissues of treated mice at 8, 9.5, 11, and 15.5 months | [249] |

| 0.3 mM melatonin dissolved in 2 mM ammonium acetate | In vitro study—Aβ peptide (1–40) β-sheet/fibril formation | Inhibited β-sheet formation by targeting hydrophobic Aβ-peptide segment (29–40) intermolecular activities | [250] |

| 1 nM–200 µM melatonin | In vitro study—Aβ synthetic peptides (1–40) and (1–42) β-sheet/fibril formation | Progressive reduction of Aβ1–40 β-sheet structures to 24% after 24 h incubation; immediate reduction of Aβ1–42 β-sheet structures from 89% to 65%, decreasing to 59% after 4 h; complete disaggregation into amorphous material after 6 h (100 μM melatonin, 250 μM Aβ1–40 peptides) | [251] |

ppm: parts per million; w/w: weight per weight

Note. Adapted from “Light, Water, and Melatonin: The Synergistic Regulation of Phase Separation in Dementia” by Loh D, Reiter RJ. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:5835 (https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24065835). CC BY.

The conundrum of resolving contradictory results from in vivo and in vitro experiments on melatonin and amyloid disaggregation

The results obtained from in vivo studies delineated a distinct dose- and time-dependent relationship between melatonin supplementation and the prevention of amyloid deposition-induced neurodegenerative symptoms in healthy and diseased animals tested. The highest melatonin supplementation recorded in the experiments in Table 2 was 6 mg/day in drinking water administered to transgenic Tg2576 AD mice for 11.5 months, starting at 4 months of age [242]. Compared to the same Tg2576 mice given ~65 µg melatonin per mouse in drinking water for only 10 weeks [247], the differences were stark. Transgenic AD mice supplemented with high-dose melatonin (HDM) exhibited lower mortality rate similar to non-transgenic mice. The brains of HDM-treated animals showed impressive declines in oligomeric Aβ40 and Aβ42 compared to same-age untreated controls. It is noteworthy that HDM treatment significantly elevated lymphatic clearance of soluble monomeric Aβ40 and Aβ42 peptides in transgenic AD mice compared to non-treated wildtype controls [242]. Tg7256 AD mice supplemented with a 92-fold reduction in melatonin in drinking water, starting 10 months later, for a total duration of only 10 weeks, fared poorly. These mice showed disappointing results where melatonin treatment failed to reduce neither brain Aβ levels nor oxidative damage [247].

Recent advances begin to reveal that the wide range of molecular mechanisms employed by melatonin to improve cognitive function and reverse amyloid-induced cognitive impairment are dependent upon the regulation of phase separation. By modulating BC dynamics, melatonin effectively adjusts the behavior of immune system mediators such as the NOD-like receptor family, pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome and transcription factor EB (TFEB) [238, 252, 253]. Melatonin regulation of phase separation processes that drive the fibrillization of amyloids reflects an ancient synergistic relationship dependent upon ATP and other molecular interactions. Consequently, the variation and fluctuation in these conditions may explain the discrepancies and inconsistent results observed in both in vitro and in vivo studies examining the ability of melatonin to prevent and/or disassemble amyloid aggregates.

Melatonin disassembly of amyloid aggregates is dependent upon hydrophobic molecular interactions and ATP

Early in vitro experiments reported that melatonin concentrations as low as 10 μM began to inhibit aggregation of Aβ1–40 synthetic peptides. While at concentrations approaching 100 μM, melatonin incubated with Aβ1–40 synthetic peptides (250 μM) produced soluble, amorphous assemblies within 6 h and immediate reductions of β-sheet structures at time 0. Whereas controls using antioxidants, melatonin analogs, or Aβ1–40 synthetic peptides showed distinct Aβ-sheet fibrillization [251]. In contrast, in vitro experiments using melatonin concentration as high as 5000 μM were only able to produce unimpressive dose-dependent disassembly of preformed tau aggregates (14% with 100 μM, 54% with 5000 μM) [239]. Similarly, 200 μM melatonin failed to elicit morphological changes in preformed, full-length tau (hTau40wt) fibrils, and 5000 μM melatonin was unable to prevent aggregation, but was able to fragment the full-length tau fibrils into small, broken filaments [240]. The conflicting results between the Aβ1–40 synthetic peptide and the preformed tau fibril experiments may reflect the extent that melatonin can modulate the hydrophobic interactions that drive fibrillization during phase-separation and nucleation.

Synthetic amyloid peptides used in the late 1990s are usually monomers that have not undergone primary nucleation processes [254]. Whereas preformed fibril used in later experiments may be derived from synthetic peptides formed via nucleation. Post primary nucleation, preformed fibrils accelerate secondary nucleation events and the formation of cross β-sheet amyloid aggregates [255, 256]. The repeat domain tau (K18wt) and full-length tau were preformed, post-nucleation aggregates [239, 240, 257]. Therefore, whether melatonin is present or absent before the nucleation events can dramatically modify the outcome of aggregation and disaggregation of proteins in experiments.

The removal of water molecules from protein hydration shells drives phase separation and nucleation

Overcrowding, hydrophobic, and electrostatic interactions are understood to drive phase separation of Aβ peptides, where solid-liquid interfaces serve as sites for heterogeneous primary and accelerated secondary nucleation events [115, 255]. In particular, dehydration—the removal of water molecules from protein hydration shells into bulk water—is the central player in the entropy tug-of-war in phase separation thermodynamics during condensate formation, where released water gains entropy and confined water molecules in the dense phase are penalized entropically [258–260]. In dehydration, the resultant positive change in water entropy promotes nucleation where amyloid aggregation is accomplished via the release of water molecules surrounding hydrophobic, monomeric amyloid peptides [261, 262]. Accordingly, the hydrophobic collapse [134, 263] of amyloid protofilaments as a result of the release of water molecules leads to amyloid aggregation, and the increase in ion concentration that augments the salting-out effect also produces similar aggregation effects [264, 265]. The phase separation of tau droplets into gel-like states before transitioning into cytotoxic fibrils that are associated with NDDs is also fueled by the dehydration of hydrophobic protein residues [266, 267].

Therefore, the presence of melatonin in the critical stage where water is expelled from hydrophobic residues may be a deciding factor that can prevent further aggregation and nucleation of amyloids. As such, the ability of melatonin to disassemble preformed, post-nucleation fibrils may reflect an important step that is present in in vivo conditions, but not necessarily in experimental setups using preformed fibrils. Unexpectedly, when preformed α-syn fibrils [268] were treated with 25 μM melatonin for 6 h, there was an obvious destabilization and reduction in fibril aggregates and the formation of shorter fibrils. At compound:peptide ratios of 5:14 and 2:14, 25 μM and 10 μM melatonin completed blocked α-syn oligomerization, respectively. Whereas, a mere 2.5 μM concentration of melatonin at compound:peptide ratio of 1:28 was able to exert an inhibitory effect on α-syn oligomerization [244]. The effectiveness of melatonin in the disaggregation of preformed α-syn and the blocking of further oligomerization underscores a unique synergy between melatonin and ATP in the regulation of phase separation by maintaining the hydration of proteins to prevent aberrant aggregation.

The ability of melatonin to disaggregate preformed amyloids is dependent upon mitochondrial ATP production

Importantly, the differences in neuronal cell lines used and the amount of fetal bovine serum (FBS) incubated with the cells may dramatically alter the amount of ATP that may be available to interact with melatonin synergistically to solubilize and disassemble preformed fibrils. Commercially available fetal bovine sera from four different sources (Gibco Thermo Fisher, Euroclone, Microgem, and Sigma-Aldrich) were found to contain a wide range of ATP from as high as 1300 pmol/L (Gibco) to as low as 250 pmol/L (Sigma) [269]. Thus, the amount of FBS added to the testing medium may affect total ATP available. In addition, the synthesis of ATP by different cell lines including primary neurons and Neuro2A (N2a) cells under different culture conditions may also be different, leading to different experimental outcomes reported in literature [270]. Mixed neuronal cultures of mesencephalon and neostriatum were used to study the effect of melatonin on preformed α-syn fibrils. These cells were incubated in 10% FBS for 48 h and switched to 5% calf serum for the assay. No glucose was used [244]. Most commercially available FBS is collected from bovine fetuses from pregnant cows during slaughter; whereas fetal calf serum (FCS) is collected from calves under 12 months old, and may contain higher protein than FBS. The level of ATP in commercially available FCS has not been determined. Conversely, neuroblastoma N2a cells were used to study the effect of melatonin on preformed full-length tau, using 0.5% FBS and without any glucose added during experiments [240].

Primary neuron cells, but not N2a, produce ATP under glucose depleted conditions

Primary neuronal cells, including pheochromocytoma of the rat adrenal medulla (PC12) cells (cultured in 5% FBS and 4.65 mM glucose), have been reported to produce 5 mM to 150 mM of ATP under normoxic, steady-state conditions. Upon glucose depletion, the mitochondria of primary neurons have been demonstrated to continue to produce a staggering 500 mM ATP as a result of the proposed astrocyte-neuron lactate shuttle (ANLSH) [271]. Whereas, N2a cells can produce ~37 mM of ATP per mg protein when supplemented with 5% FBS and 25 mM glucose [272]. The need for a high level of glucose is potentially due to the fact that under lower FBS concentrations, N2a cells must switch to an anaerobic glycolytic phenotype that requires glucose for the continued production of ATP. When FCS was reduced from 5% to 0.1% in 8.5 mM glucose, mitochondrial ATP production in N2a cells was completely shut down, with zero ATP production. However, total ATP production in these N2a cells was basically unaltered due to the activation of anaerobic glycolysis as a compensatory mechanism [273].

The N2a cells used in the full-length tau study were treated with only 0.5% FBS [240] instead of the standard 5–10% FBS used in experiments. Furthermore, without glucose in the medium, N2a cells under 0.5% FBS may not be able to produce any ATP via anaerobic glycolysis upon total inhibition of mitochondria. Whereas, primary neurons used in the α-syn study were treated first with 10% FBS followed by 5% FCS [244]. Although the medium also lacked glucose, mitochondria of primary neurons may be able to continue the production of ATP due to the proposed ANLSH effect [271]. At the very least, merely the discrepancy in FBS used in the studies may account for a reduction of as much as 90% ATP in the tau study. On the contrary, a doubling or even tripling of ATP in the α-syn study may be possible from the high amount of FBS and FCS employed [269]. These differences in ATP available to interact with melatonin may account for the contradictory effects observed where a very low concentration of melatonin was able to effectively disaggregate preformed α-syn fibrils post-nucleation; while the opposite was observed in the disaggregation of preformed tau full-length fibrils.

Transgenic Tg2576 mice have dysfunctional mitochondria

The fact that primary neurons from transgenic Tg2576 AD mice have defective mitochondrial function with diminished capacity for maximal ATP production capacity [274] also explains why 267 mg/kg body weight (b.w.; 6 mg per mouse at 22.5 g b.w.) was a necessary, effective dose to suppress the progression of AD in transgenic Tg2576 mice and extend their survival by reducing oligomeric Aβ40/Aβ42 [242, 249]. Whereas, the supplementation with only 40 ppm melatonin in diet pellets (equivalent to ~5 mg/kg b.w.) produced impressive reductions of Aβ40 (57%) and Aβ42 (73%) in the brain cortex tissues of normal aging B6C3F1 mice with functional mitochondria [248]. This distinct and potentially compensatory relationship between melatonin and mitochondrial ATP production is evident in Lingulodinium polyedra (L. polyedra)—ancient unicellular organisms with reduced mitochondrial genomes—that produced as much as ~20 mM melatonin under stress to regulate the phase separation of guanine crystals responsible for their bioluminescence [66].

Melatonin, ATP, and the adenosine moiety effect: the energy cost-effective solution for maintaining solubility of condensates

ATP: the biphasic, universal cosolute of BCs

In 1952, ATP was first reported to function as a classic hydrotrope that can dissolve insoluble aggregates [275]. This role was independently verified in different experiments decades later [276, 277]. Recent advances reveal the unique molecular structure of ATP—comprising a high-energy, hydrophilic, negatively charge triphosphate moiety, and a hydrophobic adenine nucleobase attached to a hydrophobic ribosyl group—is the primary reason why ATP is selected as the preferred energy currency used by all living organisms to regulate phase separation [278, 279]. The emergence of life required an efficient energy transfer system. Nature selected ATP as the ultimate energy transfer system for kinetically stable and thermodynamically active phosphates despite the availability of other viable phosphate carriers [280]. In the context of phase separation, phosphate carriers release high-energy phosphates to phosphorylate peptides to form and stabilize membraneless condensates. The high negative charge of phosphates can suppress charge-charge repulsion to facilitate and initiate phase separation [281].

Both ATP and high energy phosphate carriers can engage proteins via nonspecific weak interactions that promote phase separation by displacing water H-bonds, favoring the folded state by substituting water H-bonds with triphosphate H-bonds. Nevertheless, the highly negatively charged triphosphates continue to interact with hydrophobic protein patches to cause severe aggregation [282, 283]. The triphosphate moiety of ATP has been demonstrated to enhance the fibrillization of tau K18 fibrils in vitro [284]. Whereas, the stoichiometric incorporation of ATP (0.45 mM) with oligo-lysine segments containing amyloidogenic residues drives aberrant phase separation towards the self-assembly of fibrils [285]. Yet, the attachment of the adenosine moiety distinguishes ATP from other high-energy phosphate carriers. The hydrating, aromatic adenosine moiety can shield the aggregating effects of the triphosphate moiety, solubilizing solvent-exposed hydrophobic patches via π-π, π-cation and van der Waals interactions [279, 283, 286].

Consequently, a biphasic effect—where low levels of ATP promote phase separation and aggregation, but high levels have the opposite effect—has been extensively observed and reported [278, 287]. The addition of 5 mM ATP promoted phase separation of IDP-rich HNRNPG protein via charge neutralization and conformational compaction. Whereas at levels above 24 mM, ATP reduced intermolecular contacts to dissolve condensates [288]. While the addition of merely 0.25 mM ATP to wild-type α-syn monomers was adequate to begin the induction of fibril aggregation in a dose-dependent manner. However, the continued increase of ATP results in the inhibition of α-syn aggregation. In the presence of 10 mM ATP, a significant loss in late-stage fibril aggregation was clearly indicated by a reduction of Thioflavine T (ThT) fluorescence, confirming the biphasic effect of ATP in α-syn aggregation [289].

The solubilizing effect of ATP is dependent upon the adenosine moiety

The recognition that ATP may facilitate the transition of a droplet into a fibril and back into a droplet [285, 290] supports previous computational and experimental studies that showed that at physiological levels between 0.5 mM to 10 mM, ATP prevents Aβ misfolding via stabilization through the triphosphate moiety and the solubilizing effect of the adenosine moiety [291]. Even though ATP can displace water H-bonds, altering protein hydration, leading to protein folding, the solubilizing effect of the adenosine moiety is highly effective in preventing or delaying further transitioning into insoluble aggregates. Despite the fact that hydrophobic adenosine easily binds to accessible hydrophobic sites in unfolded proteins, its solubility in water is surprisingly low [292]. However, when adenosine is combined with the hydrophilic triphosphate moiety that is surrounded by three–four layers of hypermobile water [293], its solubility is greatly enhanced. This ingenious combination results in, at minimum, an order of magnitude increase in anti-fibrillation performance compared to classic hydrotropes [292, 294].

ATP prevents amyloid fibrillization via adenosine van der Waals energy

ATP, at 10 mM concentration, delays the formation of Aβ-sheets, preventing fibrillization by inducing the formation of amorphous aggregates instead [295]. Recent advances determined the anti-fibrillation suppressive effect of ATP stems not from the high energy phosphate moiety, but rather the hydrophobic adenine moiety that increases solubility via enhanced van der Waals energies [286]. On its own, the triphosphate moiety is unable to prevent fibrillation of Aβ1–42 measured by ThT assays [292]. Whereas an analysis of individual contributions of the triphosphate, adenine, and ribose moieties of ATP towards changes in the free energy of solvation for different aggregation states of the Aβ16–22 peptide indicated that the suppressive effects of ATP on amyloid fibrillation are derived largely from adenine van der Waals interactions, followed by ribose. The ribosyl group in the adenosine moiety of ATP is attached to adenine. Together the adenosine moiety contributes ~10.0 kcal mol–1 towards van der Waals energy during aggregation studies, compared to ~3 kcal mol–1 for phosphates. Although triphosphate electrostatic interactions provided inconsequential contributions towards changes in solvation energies in aggregation studies for Aβ16–22, when triphosphates are attached to adenine and ribose, the combined suppressive effect of the triphosphate and adenosine moieties on fibrillation is the greatest [286].

Nucleation changes the course of fibril aggregation and the subsequent dissolution requirement for ATP

Nevertheless, experiments employing all-atom molecular dynamics for different force fields revealed that ATP, at 150 mM concentration, can destabilize and inhibit the aggregation of preformed Aβ16–22 peptides via π-π stacking, NH-π interactions, and dose-dependent increases in H bonding [296]. Although primary neurons are capable of producing 150 mM ATP under glucose replete conditions [271], the tested concentration of ATP in 136 organ, tissue, and cell sources obtained from the three major domains of life averaged only ~4.41 mM [297]. Consequently, the use of ATP at concentrations between 100–500 mM to dose-dependently inhibit the aggregation and dissolve preformed Aβ40 fibrils in complementary wet-lab experiment and molecular simulation may require justification [298]. It is unclear why a wide range of ATP, from 10 mM to 500 mM, is required to inhibit and dissolve amyloid aggregates. The fact that wild-type α-syn monomers require only 10 mM ATP, but Aβ16–22 prefibrils and Aβ40 preformed aggregates require 150 mM and 500 mM, respectively, to dissolve aggregates reveals the important step in nucleation that changes the course of fibril aggregation. Viruses including SARS-CoV-2 are convenient catalysts that promote aggregation of amyloids via heterogeneous nucleation [152]. Consequently, the ancient synergistic relationship between melatonin and ATP becomes even more critical in the prevention and inhibition of amyloid aggregation as the result of viral infections and viral persistence.

Melatonin compensates for low ATP availability

The potential requirement for exceptionally high concentrations of ATP to inhibit and dissolve aggregates post nucleation events could present living organisms, especially early unicellular organisms without mitochondria, with an energetic cost challenge that is detrimental to survival. The efficient management of proteostatic energetic cost confers significant survival advantages during evolution [157]. This advantage is further enhanced when smaller proteins with low production and maintenance cost, including melatonin, are utilized. It is not a coincidence that the molecular mass of the penultimate, rate-limiting enzyme in the melatonin biosynthetic pathway—serotonin N-acetyltransferase (SNAT)—is only ~15-, ~17-, and 23-kDa in archaea, cyanobacteria, and humans [arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase (AANAT)], respectively [60, 299, 300]. In comparison, the molecular mass of the ATPase enzymes responsible for the production of ATP is ~730-, ~545-, and ~592-kDa in archaea, bacteria (E. coli), and humans, respectively [301–303].

Unicellular dinoflagellates, including L. polyedra, have significantly reduced mitochondrial genomes, comprising only three protein-coding genes, while the majority of 45 other genes are permanently lost and the remainder transferred to the nucleus [304]. Under duress, L. polyedra may not be able to elevate ATP synthesis to regulate the phase separation of guanine crystals that control their bioluminescence. Instead, L. polyedra increases melatonin synthesis from ~1 μM to staggering levels of as much as ~20 mM (4.61 μg/mg protein) [66, 305]. The synthesis of extreme levels of melatonin by L. polyedra to regulate the phase separation of guanine crystals is highly reminiscent of in vivo studies that administered HDM (267 mg/kg b.w.) to transgenic AD mice with dysfunctional mitochondria [242]. Despite the potential effects of reduced ATP concentration in neurons of transgenic mice [306], HDM was able to suppress the formation of oligomeric Aβ40/Aβ42 and markedly increase the glymphatic clearance of soluble Aβ40 and Aβ42 compared to untreated mice at the same age [242].

Melatonin forms H-bonds with water and stacks with the adenine moiety

Melatonin is able to compensate for lower ATP concentration and reduced solubilizing capacity, by enhancing the adenosine moiety. Melatonin is an amphiphile with hydrophobic parts that change the conformation of melatonin in the presence of water molecules as a result of the hydrophobic effect [307]. Even though melatonin has low solubility in water, it can form stable H-bonds with water. Car-Parrinello molecular dynamics and ultraviolet/infrared spectroscopy studies indicate that melatonin possesses five distinct H-bond sites for water. Melatonin’s amide NH and indole NH groups are H-bond donors to water molecules. Conversely, the amide carbonyl, methoxy oxygen, and indole π cloud of melatonin accept H-bonds from water molecules. Helmholtz free energy studies reveal that water hydrogen molecules when coordinated with the O of the amide group can exhibit an infinite average residence time due to the high degree of stability [308, 309]. Just one single water molecule attached to melatonin changes its conformational preference, where strong H-bonds produce substantial electronic frequency shifts [309] that can affect how melatonin reacts with other molecules, especially free radicals [310].

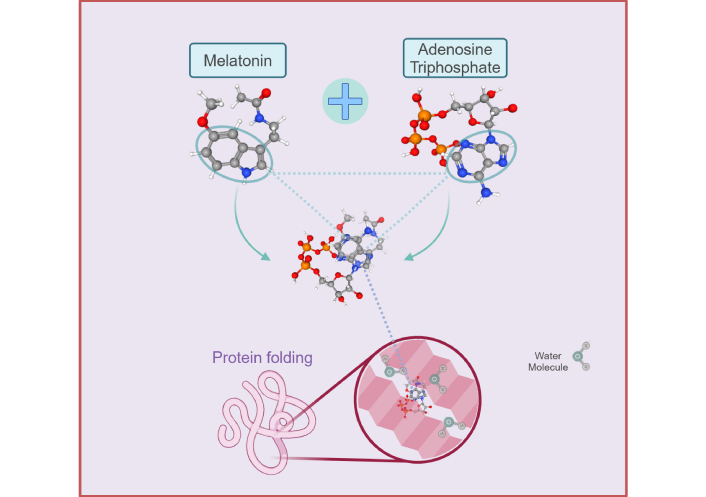

The adenosine moiety of ATP has a high structural homology to the indole moiety of melatonin (Figure 2). The aromatic indole side chain of tryptophan has been clearly demonstrated to stack comfortably with the aromatic ring systems of adenine in experiments testing molecular interactions between ATP and homopeptides [292]. The dominant π-π-stacking interactions observed between the adenosine moiety and indoles [281] may explain the synergistic association between melatonin and ATP in the regulation of phase separation that began close to 4 Ga [66]. The homologous affinity permits effortless stacking of the indole ring in melatonin with the adenine nucleobase in ATP. Melatonin is not only hydrophobic, but is also capable of binding water molecules that can enhance the solubilizing effect of the hydrophobic adenosine moiety. The stacking of aromatic side chains between tryptophan and adenine in ATP can elevate the van der Waals attraction energy to 83 kJ/mol [292]. The delocalized π-systems of melatonin not only confer increased stability, but also greatly enhance the anti-fibrillation suppressive effects of the adenosine moiety of ATP (Figure 2) [292, 311].

Diagram depicting the homologous molecular structures between melatonin [312] and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) [313] that augment the adenosine moiety effect of ATP in the regulation of protein folding and phase transitions during phase separation. The hydrophobic adenine significantly enhances the solubilizing effect of ATP to prevent aggregation of phase-separated proteins as a result of hydrophobic interactions with the triphosphate moiety. The aromatic indole ring of melatonin can stack comfortably with the adenosine moiety to further promote its hydrating effect via van de Waals interactions that effectively prevent the aggregation of solvent-exposed hydrophobic patches induced by the triphosphate moiety of ATP. Created in BioRender. Loh, D. (2025) https://BioRender.com/t35s942

Therefore, increased melatonin in the vicinity of ATP may significantly elevate the solubilizing effect without the need to increase total ATP concentration. Early organisms may have depended upon this synergy to manage proteostatic energy costs and enhance survival advantage. Conversely, an absence or reduction in melatonin would require extremely high levels of ATP to inhibit further progression of amyloid aggregates post nucleation. Untargeted metabolomic analyses measured both ketone bodies and metabolites derived from the glycolytic and pentose phosphate energy metabolism pathways collected from postmortem prefrontal cortex brain tissues from AD and subjects without clinical AD diagnosis. The results obtained revealed a significant deficit in global energy metabolism in the brains of AD patients [314]. The dramatic reduction in pyruvate essentially suppresses mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). Without the chemical reduction of pyruvate, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) cannot be regenerated to fuel continued glycolysis that supplies the reduced form of NAD+ (NADH)—the essential source of reducing equivalents—for the mitochondrial tricarboxylic cycle and the electron transport chain during OXPHOS [315, 316].

Reduced production of ATP suppresses slow wave sleep and impedes effective clearance of amyloid aggregates

The strong correlation between sleep and the clearance of brain waste has been clearly identified in literature [216–218]. The exact molecular mechanism responsible for the evidence reported remains elusive. In order to sustain synaptic transmission, neurons require approximately 40% of total ATP produced in the cortex [317]. Whereas during slow wave sleep, the surge of ATP from the reduction of neuronal activity [318] may be critical in facilitating the solubilization of amyloid crystals for removal by the CSF and associated waste-clearing systems. Since the adenosine moiety of ATP is largely responsible for the solubilizing effect of ATP as a hydrotrope, it is not surprising that increased adenosine levels in the CSF enhances both glymphatic flow and clearance of wastes in rodent models [319]. Conversely, fragmentation of slow wave sleep may lead to insufficient ATP in the CSF that not only prevents the effective solubilization and clearance of amyloid aggregates, but also the ability to utilize melatonin for the enhancement of the solubilizing effect of the adenosine moiety. Thus, the puzzling phenomenon of increased circulating melatonin associated with slow wave sleep fragmentation may merely reflect a deficiency in ATP during slow wave sleep [208].