Affiliation:

1Department of Neurosurgery, Cairo University, Cairo 11562, Egypt

Email: mohammed.azab@kasralainy.edu.eg

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3934-0470

Affiliation:

2Department of Neurosurgery, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32610, USA

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6577-4080

Explor Neuroprot Ther. 2023;3:177–185 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/ent.2023.00046

Received: December 06, 2022 Accepted: May 22, 2023 Published: August 23, 2023

Academic Editor: Rafael Franco, Universidad de Barcelona, Spain

The article belongs to the special issue Emerging Concepts in Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

The management of symptomatic chronic subdural hematoma (CSDH) is surgical evacuation and prognosis in most cases is good. Tension pneumocephalus is the presence of air under pressure in the intracranial cavity. A case of tension pneumocephalus developing as a complication of burr hole evacuation of CSDH is illustrated. In this case, tension pneumocephalus was managed by reopening the wound and saline irrigation with a subdural drain placement. Considering this case report and after a careful review of the literature, the physiopathology, diagnosis, and treatment of this complication are highlighted in the article.

Tension pneumocephalus is a rare but catastrophic intracranial condition in which entrapped air under pressure can act as a space-occupying lesion [1–3]. It can be fatal if not promptly diagnosed and properly treated. In the majority of neurosurgical operations, the amount of air is small and rarely causes any neurological problems [4]. Symptomatic chronic subdural hematoma (CSDH) can be managed with a simple twist drill craniostomy or a formal craniotomy [5–7]. The possibility of reaccumulation should be high in patients who do not recover well after surgery [5, 7]. One of the uncommon but underestimated causes of postsurgical delayed recovery in CSDH cases is tension pneumocephalus [4, 7].

It is essential to recognize the deleterious effect of postoperative tension pneumocephalus in patients undergoing neurosurgical procedures. This is a case of tension pneumocephalus after the surgical evacuation of symptomatic CSDH with a literature review.

A 75-year-old male patient presented to the emergency department at Cairo University Hospital with a disturbed consciousness level [Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) 8]. By history taking, the patient deteriorated over 5 days until one of the family members brought him to the hospital. Medical history is relevant for diabetes mellitus and hypertension which are well controlled with medications. Intubation and resuscitation were initiated. Basic labs and urine analysis for drugs came back within the reference values. Computed tomography (CT) of the head showed a left CSDH. On the same day of admission, the patient was admitted to the surgical theater. The patient was placed in the supine position with the head turned to the unaffected side. About 3–5 cm longitudinal incision was made over the scalp area corresponding to the thickest part of the hematoma. Under general anesthesia, he underwent two burr hole evacuations over the thickest parts of the hematoma. The dura was coagulated with bipolar coagulation. The dura was then cut in a cruciate incision. Irrigation with warm normal saline through the burr holes and through the catheter was done intermittently in all directions and also during the closure of the skin. We repeated irrigation until the effluent became clear. A silicone drain was inserted subcutaneously in each wound and connected to a sterile drainage bag. The patient was then transferred to the intensive care unit. By night, the patient started to improve, and GCS was 15. The patient was extubated and vitally stable. The drain was removed two days postoperatively. On day 3, the patient appeared confused and agitated with blood pressure spiking to 190/100 mmHg (25.33/13.33 kPa, 1 kPa = 7.50062 mmHg). An emergency CT of the head showed subdural pneumocephalus with the underlying brain looking effaced (Figure 1). Reopening of the wounds and continuous irrigation with warm saline solution through an IV line was done, we noticed a gush of air bubbles coming out of the burr hole, then a silicone drain was inserted in the subdural space. Patient recovery was uneventful with GCS 15 and he was maintained in a flat position. Before discharge, a repeat CT shows the resolution of the trapped air. One week later, the patient was fully conscious and vitally stable.

CSDH is a common neurosurgical problem that is frequently encountered in clinical practice and its prognosis is excellent when properly managed [6–8]. Simple pneumocephalus is commonly encountered after surgical evacuation of CSDH and is usually asymptomatic [9]. However, when the air is trapped under pressure, it may lead to neurological deterioration. In a study that involved 19 cases of CSDH, Bremer and Nguyen [10] reported a 16% incidence of subdural tension pneumocephalus. Ishiwata et al. [11] reported a 2.5% incidence of postoperative tension pneumocephalus in 196 patients operated for CSDH. Identifying this complication is possible through clinical observation and the potential use of CT. Clinical and radiological manifestations of increased intracranial pressure (ICP) are a guide for diagnosing tension pneumocephalus. The typical CT finding of pneumocephalus is the subdural air separating the bilateral frontal lobes and resembles the shape of Mount Fuji [12, 13]. Monajati and Cotanch [14] reported that the presence of midline shift is an indication of unilateral subdural tension pneumocephalus.

A tear in the arachnoid membrane may help air to enter the subarachnoid space. A suggested pathogenic mechanism is the ball valve theory [15]. The external pressure allows the flow of air to the inside of the cranium and when air pressure within the intracranial space equals the external air pressure, air gets trapped [15]. Another mechanism is that excess drainage of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) creates a negative pressure that leads to an influx of air intracranially [16]. There are several causes of tension pneumocephalus such as trauma, previous surgery, use of nitrous oxide inhalation anesthesia, lesions involving the paranasal sinuses, and certain infections [17, 18]. Trapped air is harmful to neurons and can cause more damage to the already affected brain parenchyma [19]. CSDH frequently occurs in the elderly and the brain volume in this age group does not allow for re-expansion after drainage which facilitates subdural air collection.

The literature was reviewed for the published cases of tension pneumocephalus after surgical evacuation of CSDH and a summary of the published cases from 1980 to 2022 is illustrated (Table 1). Tension pneumocephalus is a reported complication of the surgical evacuation of CSDH [10, 11, 14, 20]. Tension pneumocephalus may manifest with a wide range of clinical presentations, including restlessness, impaired consciousness, focal neurological deficits, and even cardiac arrest [21]. The most common presentation reported in the literature was impairment of the conscious level [10, 11, 14, 20–23].

Summary of tension pneumocephalus cases after surgical evacuation of CSDH in the literature

| Authors | Year | Number of CSDH cases | Number of cases with tension pneumocephalus | Age | Clinical presentation | Days after primary surgery | Drain | Management | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bouzarth et al. [22] | 1980 | 5 | 5 | 59–80 | Impaired consciousness | 3 days | Subdural | Case 1: craniotomy; case 2: subdural aspiration; case 3: catheter removal; case 4: subcutaneous aspiration; case 5: subdural suction | All cases improved |

| Monajati and Cotanch [14] | 1982 | 6 | 1 | 86 | Right arm weakness and speech difficulty | 2 days | Subdural | Subdural tap | Weakness improved |

| Bremer and Nguyen [10] | 1982 | 19 | 3 | 60–80 | Agitation and impaired consciousness | 2 days | N/M | Case 1: emergency craniotomy; case 2: emergent catheter aspiration; case 3: suctioning | Case 1: no improvement; case 2: improved; case 3: improved |

| Caron et al. [24] | 1985 | N/M | 1 | 74 | Impaired consciousness | N/M | Subdural | Burr hole drainage of the air and lumbar catheter Elliott solution infusion | Improved |

| Kawakami et al. [25] | 1985 | N/M | 1 | N/M | N/M | N/M | N/M | Closed system drain | Improved |

| Atluru and Kumar [26] | 1987 | N/M | 1 | 10 weeks | Macrocephaly, diffuse hypertonia, and hyperreflexia with marked head lag | 1 day | N/M | Needle aspiration | Improved |

| Ishiwata et al. [11] | 1988 | 196 | 5 | 70–86 | Impaired consciousness | 6 h–2 days | N/M | Burr hole evacuation | All cases improved |

| Sharma et al. [4] | 1989 | 63 | 5 | 6–60 | Drowsiness and impaired consciousness | 5–24 h | N/M | Drill craniostomy and aspiration | All cases improved |

| Lavano et al. [23] | 1990 | 7 | 7 | 40–85 | Impaired consciousness | N/M | N/M | Case 1: aspiration of the air, spinal saline infusion; case 2: craniotomy; case 3: burr hole with catheter aspiration; case 4: craniotomy with removal of the air and a membrane; case 5: craniotomy with removal of the air and a membrane; case 6: burr hole evacuation; case 7: burr hole evacuation no improved than craniotomy | All cases improved except case 7 died due to pneumonia |

| Merlicco et al. [27] | 1995 | 70 | 5 | > 70 | Impaired consciousness | 12 days | N/M | N/M | Three cases died, one due to a medical cause; the other 2 cases improved |

| Mori and Maeda [28] | 2001 | 500 | 4 | N/M | Impaired consciousness | N/M | Subdural | Reopening the wound and burr hole evacuation | All cases improved |

| Cummins [29] | 2009 | N/M | 1 | 78 | Impaired consciousness | N/M | Subdural | Catheter aspiration | Improved |

| Shaikh et al. [20] | 2010 | N/M | 1 | 70 | Impaired consciousness | 3 days | Subdural | Aspiration and catheter insertion | Improved |

| Ihab [30] | 2012 | 50 | 2 | 60 and 62 | Case 1: impaired consciousness; case 2: headache | N/M | N/M | Conservative case 1: simple aspiration; case 2: nursing in a flat position, administration of fluids, and supplemental breathing of 100% O2 | Both cases improved |

| Mehesry et al. [31] | 2016 | N/M | 1 | 68 | Increased right arm weakness and expressive aphasia | N/M | Subdural | Conservative management | Improved |

| Balevi [32] | 2017 | 148 | 8 | N/M | N/M | N/M | Subdural | Closed subdural drainage | All cases improved |

| Turgut and Yay [33] | 2019 | N/M | 1 | 59 | Seizures | 3 days | Subcutaneous | Burr hole evacuation | Improved |

| Moscovici et al. [34] | 2019 | 45 | N/M | > 90 | N/M | N/M | N/M | Conservative management | N/M |

| Dobran et al. [35] | 2020 | 153 | 2 | N/M | N/M | N/M | N/M | Burr hole evacuation | All cases improved |

| Celi and Saal [36] | 2020 | N/M | 1 | 85 | Rapid neurological deterioration | 2 days | Subdural | Conservative management | Death |

| Lepić et al. [37] | 2022 | N/M | 1 | 81 | Hypertension | N/M | Subdural | Emergency irrigation | No improvement and no further surgery was needed |

O2: oxygen; N/M: not mentioned

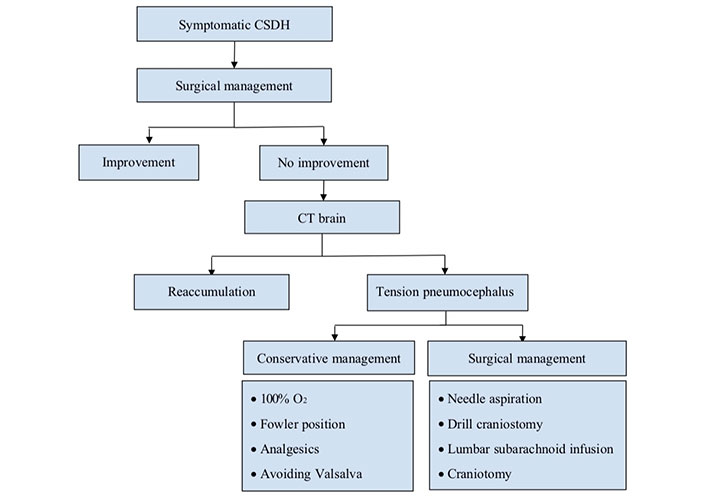

Simple pneumocephalus usually gets absorbed without causing any complications unless there is an infection or CSF fistula [38]. The conservative management includes adjusting the patient in a semi-sitting position of 30°, avoiding maneuvers that increase the ICP, analgesics, antipyretics, and hyperbaric oxygenation [39, 40]. One hundred percent O2 was also suggested as a possible treatment line [22, 29, 32, 35]. Due to pulmonary toxicity, O2 therapy can be allowed for a maximal duration of 24–48 h only. In case of failure of the conservative management with worsening of the patient’s condition, surgical evacuation of the air is mandated (Figure 2). Needle aspiration was tried in some reported cases [20, 22, 30]. Some surgeons removed the air through burr holes and drill craniostomy [4, 11, 28, 36]. Caron et al. [24] managed their case by craniotomy drainage and continuous lumbar subarachnoid solution infusion. An external ventricular drain can be also inserted for the drainage of air [41]. Other surgeons managed their cases with emergent craniotomy [10, 22]. Doron et al. [42] used a subdural evacuating system to drain air and fluid from the subdural space.

Flux diagram describing the procedure when suspecting tension pneumocephalus after surgical evacuation of CSDH

For the prevention of tension pneumocephalus, a closed drainage system is advised. Tension pneumocephalus was not observed in any patient with inserted closed system drain [43]. Erol et al. [44] compared the results of the CSDH patients that underwent burr hole craniostomy and irrigation with those undergoing a closed system drainage. The incidence of pneumocephalus was increased in the irrigation group [44]. In our case, the excess intermittent irrigation of saline may be a possible cause of postoperative pneumocephalus. Irrigation, if done, should be continuous as much as possible and a closed drainage system is more favorable.

Other suggested methods for reducing the incidence of postsurgical pneumocephalus are overhydrating the patient and endolumbar administration of saline [23]. A subcutaneous reservoir connected to a catheter can be also inserted in the subdural space to withdraw the entrapped air [45]. Cecchini [46] described a temporary double inverse air-fluid drainage technique for avoiding pneumocephalus. Meningeal defects should be avoided as much as possible as it invites much air flux in the subarachnoid spaces.

There is a controversy in the literature regarding the effect of head position on the incidence of postoperative pneumocephalus. Some authors prefer to elevate the head of the patients [47, 48], while others prefer to keep the patient in a flat position [30, 49]. The position of the burr hole itself may affect the incidence of pneumocephalus. Dobran et al. [35] suggested that the anterior-posterior burr hole position causes less air collection than the cranio-caudal position. An active bone hole drainage system was described by Zhang et al. [50] to reduce the incidence of postoperative pneumocephalus after the evacuation of CSDH. After regular irrigation and the subdural drainage tube is placed, they designed two small bone holes, slightly smaller than the main one, on both sides of the main burr hole in a longitudinal direction. Then, they placed the head end of the bone hole drainage tube into two small bone holes. The irrigation water pressure will push the subdural air out of the subdural space and air will be discharged through the bone hole drainage tube [50]. In conclusion, tension pneumocephalus is an underestimated complication of surgical evacuation of CSDH. It is essential for practicing neurosurgeons to be aware of the possibility of this complication and the proper management.

CSDH: chronic subdural hematoma

CT: computed tomography

GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale

O2: oxygen

MAA: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft. AH: Methodology, Data curation. BLW: Supervision, Writing—review & editing.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The manuscript entitled “Tension pneumocephalus as a complication of surgical evacuation of chronic subdural hematoma: case report and literature review” complies with the declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethical Committee of Cairo University Hospital Department of Research with a reference number C156634.

Informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from all participants.

Informed consent to publication was obtained from relevant participants.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2023.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2023. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 5773

Download: 50

Times Cited: 0

Eric J. Panther, Brandon Lucke-Wold

Stephan Quintin ... Brandon Lucke-Wold

Fettah Eren ... Sueda Ecem Yilmaz

Gonçalo Januário

Andrés Ricaurte-Fajardo ... Nathalia Melo Gonzalez