Abstract

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) is a multiorganic syndrome that affects the cardiovascular, neurologic, renal, and gastrointestinal systems with an incidence ranging from 0 case to 67 cases per one million person-years, and its pathophysiology remains unknown. It is believed that genetic factors, the environment, and changes in immune system function contribute to the development of EGPA, overlapping the immune mechanisms of vasculitides and the pathologic mechanisms in eosinophilic syndromes. This disease is commonly divided into two phenotypes depending on the presence of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA). ANCA-positive patients usually have more vasculitic manifestations like peripheral neuropathy, purpura, renal involvement, and biopsy-proven vasculitis. The keystone of EGPA therapy is systemic corticosteroids (CS) as monotherapy or in combination with other immunosuppressive treatments, and recently the efficacy of eosinophil-targeted biotherapy, anti-interleukin-5 (IL-5), has been shown to be efficacious in EGPA. Although this phenotype/phase distinction has not yet had an impact on the current treatment strategies, emerging targeted biotherapies under evaluation could lead to a phenotype-based approach and personalised treatment regimens for EGPA patients. The present review describes the new therapeutical approaches with biological drugs for EGPA.

Keywords

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, biological therapies, c-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, mepolizumab, benralizumab, reslizumab, omalizumab, rituximabIntroduction

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA), previously known as Churg-Strauss syndrome, is one of the antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA)-associated vasculitides [1]. In accordance with the latest International Chapel Hill Consensus, it is an eosinophilic and necrotizing granulomatous vasculitis affecting small to medium vessels, the respiratory tract, where bronchial asthma and chronic rhinosinusitis are the main characters [1, 2]. It is a multiorganic syndrome with a wide range of manifestations, affecting the skin, neurologic, cardiovascular, renal, and gastrointestinal systems [1, 2]. It is a very rare disease with an incidence ranging from 0 case to 67 cases per one million person-years [3].

Over 30 years ago, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) published classification criteria for EGPA. However, these criteria have never been validated due to the small number of patients included, which were developed using data from only 20 patients [4]. It is not until 2022 that the ACR/European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) endorses and publishes the new classification criteria for EGPA [5]. However, it is necessary to know that the Birmingham vasculitis activity score (BVAS) is a validated tool with different items that allows the identification of disease activity in patients diagnosed with EGPA [6].

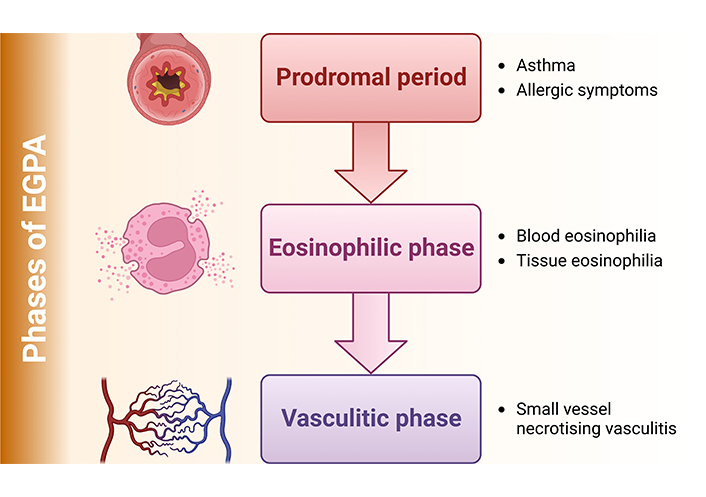

To understand how EGPA affects patients, this disease is often classified into two phenotypes based on the presence of ANCA targeting myeloperoxidase (MPO) status [7–9]. MPO-ANCA are present in about 31% and 38% of patients and are associated with the vasculitis pattern of the disease. In juxtaposition, patients without MPO-ANCA are at risk of cardiac involvement, being the main cause of morbidity and mortality [7–9]. ANCA-positive patients are more likely to have features of vasculitis with peripheral neuropathy, purpura, renal involvement, and biopsy-proven vasculitis [9]. It is important to emphasize that 3 phases characterize EGPA (Figure 1) that can overlap and progress at varying intervals: the prodromal period, where asthma and other allergic manifestations are the main features; the eosinophilic phase with blood and tissue eosinophilia; and the vasculitis phase with small vessel necrotising vasculitis [1, 10].

Although this phenotype/phase distinction has not yet had an impact on the current treatment strategy, emerging targeted biotherapies under evaluation could lead to a phenotype-based approach and personalised treatment regimens for EGPA patients [9].

The present review describes the new therapeutical approaches with biological drugs for EGPA.

Pathogenesis

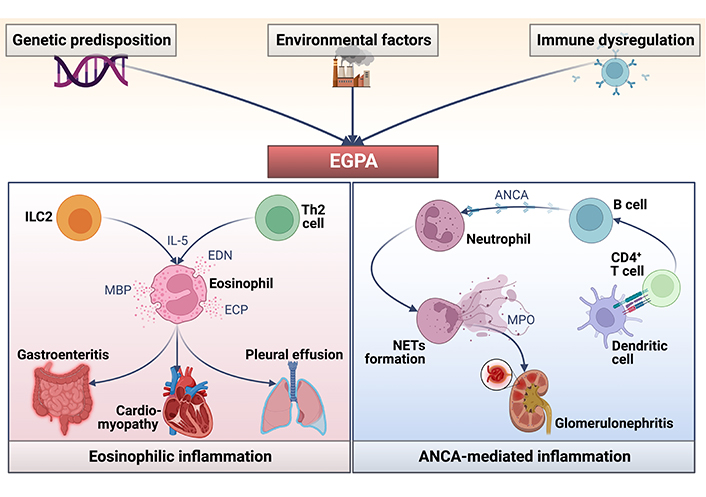

The pathogenesis of EGPA is still an unknown subject. Several factors are thought to contribute to its pathophysiology. Genetic predisposition and epigenetic changes are factors that dysregulate the proper functioning of the immune system and contribute to the development of EGPA (Figure 2) [7]. There has even been a recent case report of a patient who developed EGPA after the RNA-coronavirus disease (COVID) vaccine [11]. It is considered by many authors to be an overlap between the immune mechanisms of vasculitides and the pathological mechanisms in eosinophilic syndromes [7, 10].

Pathophysiology of EGPA. ICL2: intracellular loop 2; IL-5: interleukin-5; EDN: eosinophil-derived neurotoxin; Th2: T helper 2; MBP: major basic protein; ECP: eosinophil cationic protein; NETs: neutrophil extracellular traps

Eosinophils are thought to play a significant role in the pathogenesis of EGPA [1, 10, 12] because they participate in all three stages of the disease [1, 10]. Eosinophils release their granules containing stored cytotoxic proteins and toxins such as EDN, MBP, eosinophil peroxidase, and ECP, leading to tissue damage [12]. The increase in blood and tissue eosinophils is widely thought to be the result of Th2 cytokine production by CD4+ T cells, particularly IL-5, the most potent stimulator of eosinophil proliferation and functional activation [13–15].

IL-5 is increased in patients with EGPA in active disease and can promote the adhesion of eosinophils to vascular endothelium. Thus, the elevated production of IL-5 may be relevant pathogenetically, not only for eosinophilia but also for the development of vasculitis by promoting transvascular migration and functional activation of eosinophils [14–17]. Most of the biological therapies being studied are aimed at blocking this IL. Despite the complex pathophysiological mechanisms associated with EGPA, much progress has been made in understanding the mechanisms underlying EGPA; however, further studies are needed to clarify its pathophysiology.

Classification criteria for EGPA

Recently in February 2022, the ACR and EULAR published the new validated classification criteria for EGPA [5]. This classification should be applied to categorize a patient as having EGPA when a diagnosis of small or medium-vessel vasculitis has been suspected. These criteria are divided into clinical criteria and laboratory and biopsy criteria. A score ≥ 6 is needed for the classification of EGPA [5], as can be seen below:

Clinical criteria:

Obstructive airway disease (+ 3)

Nasal polyps (+ 3)

Mononeuritis multiplex (+ 1)

Laboratory and biopsy criteria:

Blood eosinophil count ≥ 1 × 109/L (+ 5)

Extravascular eosinophilic-predominant inflammation on biopsy (+ 2)

Positive test for cytoplasmatic ANCA (cANCA) or antiproteinase 3 (anti-PR3) antibodies (– 3)

Hematuria (– 3)

The keystone of EGPA therapy is systemic corticosteroids (CS) used as monotherapy or in combination with other immunosuppressive agents (ISAs) [1, 9, 12]. The therapeutic choice is guided by the type and severity of organ involvement and scoring systems, defined by the Five Factor Score (FFS) [18]. An FFS of 0 signifies non-severe disease without organ involvement, and an FFS of ≥ 1 depicts severe disease with organ involvement. Therefore, if FFS is 0, systemic glucocorticoids are used as monotherapy. If FFS ≥ 1 or life-threatening or organ-threatening symptoms, ISAs including azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, mofetil mycophenolate, or rituximab (RTX) are added to the CS [9, 12].

CS has been associated with notably improved remission rates and reduced disease mortality [18]. However, to date, no controlled trials have ever been made, and it is inevitable that CS changed EGPA prognosis [9].

ISAs, as previously mentioned, are commonly prescribed in combination with CS to treat severe EGPA [1, 9, 12]. Cyclophosphamide is the most ISAs defined to control severe vasculitis manifestations and is the first choice for cardiac involvement [1, 18–20].

Methotrexate and azathioprine are given, after cyclophosphamide induction, as maintenance therapy or when cyclophosphamide is contraindicated [8, 18]. After remission, the most used in the maintenance phase are methotrexate, azathioprine, or mofetil mycophenolate [1, 21–23].

For refractory disease, relapses, problems associated with CS dependence, and asthma symptoms that often persist after the vasculitis is in remission, effective agents that have successfully treated other eosinophil-related disorders are currently being developed, creating new therapeutic possibilities for patients with EGPA [9]. Continuing advances in research and the development of new biological therapies have demonstrated the efficacy of an eosinophil-targeted biotherapy, anti-IL-5 to be effective in EGPA [9, 12, 24]. However, further studies are needed to determine which patients with EGPA would benefit from these targeted therapies.

New targeted therapies

Mepolizumab

Mepolizumab is a humanized immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) kappa monoclonal antibody (mAb) against free IL-5 that selectively inhibits eosinophilic inflammation [12, 25, 26]. Mepolizumab prevents IL-5 from binding to the α-subunit receptor, predominantly expressed in human eosinophils [7, 12, 27]. Due to its characteristics, mepolizumab has been investigated to treat eosinophils-related disorders such as atopic dermatitis, chronic rhinosinusitis, hypereosinophilic syndrome, and severe eosinophilic asthma and EGPA has recently been included in the therapeutic range. In 2015, mepolizumab was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) as an add-on therapy in severe eosinophilic asthma at a dose of 100 mg every four weeks [12, 24, 28, 29], resulting in a reduction in asthma exacerbations and the need for systemic CS treatment [26].

In 2010 was published the first case report of the successful use of mepolizumab was in a patient with refractory ANCA-negative EGPA. The patient presented hypereosinophilia and interstitial pneumonia with 60% eosinophils in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and myocarditis. They started 750 mg of intravenous (IV) mepolizumab every four weeks, achieving normalization of blood eosinophils counts and asthma control after the first dose. However, the asthma control test (ACT) or lung function was not reported in this study. Complete normalization of chest tomography was developed after the second infusion, persisting after 6 months [30].

Subsequently, a small open-label pilot study treated 7 CS-dependent EGPA patients with 750 mg IV mepolizumab every 4 weeks for 4 months. They demonstrated that mepolizumab allowed substantial CS tapering while maintaining clinical stability. However, on mepolizumab cessation, the EGPA manifestation recurred, necessitating CS bursts with a more gradual resurgence of the blood eosinophil percentage [31].

A follow-up study of 10 patients with refractory EGPA treated with 9 infusions of 750 mg IV mepolizumab and then switched to methotrexate to achieve remission was subsequently published [32]. CS was at as low a dose as possible to the physician’s criteria, no CS withdrawal protocol was discussed. The mean follow-up was 22 months, with 3/10 patients still in remission after 143 weeks of stopping mepolizumab. However, 66.6% had to increase the CS intake, and the eosinophils counts rose after discontinuation of mepolizumab infusions [32]. This study demonstrated that mepolizumab could induce temporary remission in EGPA in a small population.

The studies above were pivotal to progress in treating EGPA and pointed out a potential benefit of mepolizumab. However, it was not until 2017 that the EGPA mepolizumab study team published the results of the mepolizumab or placebo for EGPA or mepolizumab or placebo for eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis study (MIRRA) [24], a multicenter, double-blind, parallel-group, phase III trial of 136 patients with relapsing or refractory EGPA receiving systemic CS, 68 participants were assigned to receive 300 mg subcutaneous (SC) plus standard care every 4 weeks for 52 weeks, and 68 patients were in the placebo group. Organ or life-threatening EGPA was excluded. The MIRRA trial defined remission as a reduction in the CS dose according to its standardized program and a zero score from BVAS and prednisone ≤ 4 mg/day. Mepolizumab led to significantly more accrued weeks (≥ 24 weeks) of remission than placebo (28% vs. 3%); a higher percentage of participants in remission at both week 36 and week 48 (32% vs. 3%), and the rate of reduction of prednisone or equivalent to 4 mg/day or less per day was 44% in mepolizumab and 7% in placebo. The time to first relapse over a 52-week period was significantly longer in participants who received mepolizumab than those who received a placebo (56% vs. 82%), and vasculitis relapses occurred in 43% in the mepolizumab group vs. 67% receiving placebo.

The MIRRA trial led to the 2017 FDA authorization of 300 mg SC mepolizumab every 4 weeks as the first drug to be approved explicitly for EGPA [24, 28].

A posthoc analysis [33] investigated the clinical benefit of mepolizumab, defined as a 50% or more significant reduction in oral CS dose during weeks 48 to 52 or no EGPA relapses. Patients in the mepolizumab group reduced the oral CS intake definition (78% vs. 32%), and 87% of patients experience no EGPA relapses vs. 53% in the placebo group [33].

After the FDA approved mepolizumab for EGPA at a monthly dose of 300 mg, a recent real-life observational study of 16 patients suggested that mepolizumab at a dose of 100 mg 4 weeks may have a role as a steroid/immunosuppressive sparing agent in patients affected by EGPA. They concluded that, despite the 100 mg dose, the proportion of patients who could discontinue oral CS was higher than in the MIRRA trial [34]. Another study reported the effectiveness of low-dose mepolizumab in 25 patients diagnosed with EGPA. A dose of 100 mg of mepolizumab was administered every 4 weeks, decreasing significantly daily CS dose with an improvement in ACT and quality of life scores. A significant reduction in asthma exacerbations and blood eosinophil was also observed. This study concluded that there was no significant difference between the dosages in terms of complete response [35].

A recent European multicenter observational study assessed mepolizumab’s effectiveness and safety of 100 mg every 4 weeks and 300 mg every 4 weeks in a cohort of 203 patients with EGPA [36]. They suggested that mepolizumab 100 mg monthly might be an acceptable and valid alternative to the 300 mg dose with a lower rate of adverse events [36]. However, caution should be exercised when interpreting these data, as some reports suggest a risk of systemic disease flare in patients receiving mepolizumab at the dose for asthma control. Further randomised clinical trials with representative sample sizes and close long-term follow-ups are needed to compare the efficacy and safety of these two EGPA treatment regimens [36]. While all these studies assess the benefit of mepolizumab treatment in the EGPA, further studies are needed to determine its long-term efficacy.

Several clinical trials with mepolizumab are currently underway: E-merge (NCT05030155) [37], mepolizumab long-term study to asses real world safety and effectiveness of eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (MARS, NCT04551989) [38], MEA115921 (NCT03298061) [39], EGPA Long-Term (NCT03557060) [40]. A summary of all relevant studies with mepolizumab can be found in Table 1.

Mepolizumab therapy in patients with EGPA

| Reference | Study design | Number of patients | Dose and route of administration | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kahn et al. [30], 2010 | Case report | 1 | 750 mg IV monthly | Blood eosinophil normalizationClinical remissionChest tomography normalizationExacerbation reduction |

| Kim et al. [31], 2010 | Open-label pilot study | 7 | 750 mg IV monthly | CS reductionReduce eosinophil countsClinical stabilityExacerbation reductionLack of improvement in pulmonary function |

| Hermann et al. [32], 2012 | Case report | 10 | 750 mg IV monthly | 9 Patients achieve clinical remissionDecrease eosinophil countExacerbation reductionPotential use to maintain remission in EGPACS reduction |

| Wechsler et al. [24], 2017 | Multicenter, double-blind, parallel-group, phase III trial | 136 | 300 mg SC monthly | Significantly weeks (≥ 24 weeks) of remission than placebo (28% vs. 3%)The reduction of prednisone was 44% in mepolizumab and 7% in the placeboFDA authorization of 300 mg SC mepolizumab every 4 weeks as the first drug to be approved explicitly for EGPA |

| Steinfeld et al. [33], 2019 | Analysis posthoc | - | 300 mg SC monthly | Patients in the mepolizumab group reduce CS intake (78% vs. 32%)87% Of patients experience no EGPA relapses vs. 53% in the placebo group |

| Carminati et al. [34], 2021 | Real-life observational study | 16 | 100 mg SC monthly | CS reductionACT score improvementExacerbation reductionNo statistically significant differences in blood eosinophil reduction and pulmonary function |

| Özdel Öztürk et al. [35], 2022 | Single-center retrospective real-life study | 25 | 100 mg SC monthly | CS reductionACT score, SNOT-22, and quality of life improvement.Exacerbation reductionReduce eosinophils countsImprove lung function |

| Bettiol et al. [36], 2022 | Multicenter observational study | 203 | 100 mg SC monthly vs. 300 mg monthly | Reduction in BVAS scoreCS reductionReduce eosinophil countsNo significant differences between 100 mg and 300 mg dose |

SNOT: sinonasal outcome test; -: blank cell

Benralizumab

Benralizumab is a mAb that binds the IL-5 receptor, thus neutralizing eosinophils via antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity [41]. The clinical efficacy of benralizumab was investigated in two independent phase III trials [efficacy and safety of benralizumab for patients with severe asthma uncontrolled with high-dosage inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting β2-agonist (SIROCCO) and benralizumab, an anti-IL-5 receptor α monoclonal antibody, as add-on treatment for patients with severe, uncontrolled, eosinophilic asthma (CALIMA)] [41, 42]. Benralizumab significantly reduced the annual exacerbation rate, improved pulmonary function, and had a glucocorticoid-sparing effect in patients with eosinophilic asthma [40–42]. Benralizumab was approved for severe asthma in 2017 in the United States, and in 2018 in European countries [41–43].

In 2019, the first case report of a 59-year-old patient with MPO-ANCA-positive relapsing EGPA with purpura, mononeuritis, and high blood eosinophilia (17,640 eosinophils) who was treated with benralizumab SC at a 30 mg was published. After three weeks after the first administration, the patient achieved blood eosinophil count normalization, improvement of respiratory symptoms, decreased oral CS intake, and MPO-ANCA antibodies negativity. They concluded that reducing the MPO-ANCA levels might be helpful in controlling EGPA disease activity [44].

Subsequently, several case reports of EGPA patients treated with at least three 30 mg doses of benralizumab have been published in recent years [45–54], and all showed a reduction in oral CS intake and clinical remission [45–55]. These results should be taken with caution because these are single-patient case reports.

However, in 2020, Padoan et al. [56] described the clinical features in a series of 5 patients with refractory, CS-dependent asthma with EGPA, treated with a 30 mg dose of benralizumab SC every 8 weeks after the initial 3 doses administered every 4 weeks. All patients had a long-standing disease with a median duration of 20 months, 20% had an MPO-ANCA positivity rate, and none had cutaneous or cardiac involvement. At baseline, the median eosinophil count was 1,200 μL, with a BVAS of 4 and all patients received an oral CS dose above 10 mg, and 2/5 patients received ISAs as standard care. After 24 weeks of benralizumab, a significant reduction in CS intake was observed. Notably, 3 of 5 patients were able to withdraw CS completely. Alongside this, a complete depletion in circulating eosinophils was observed in all patients [56]. Although patients reported better disease control with an improvement in the ACT and quality of life, there was no statistically significant difference in lung function and a lack of improvement in ANCA-status [56]. Subsequently, Nanzer et al. [57] achieved similar results in a series of 11 patients with refractory EGPA who underwent a 24-weeks benralizumab treatment. The study successfully reduced CS intake, reduced total eosinophil count and BVAS scale, and improved ACT and quality of life. However, no improvements in lung function were reported [57].

Finally, a prospective 40-week open-label pilot study of benralizumab 30 mg administered SC in 10 patients with EGPA was conducted [58]. This study showed that benralizumab was well tolerated, reduced the median prednisone dose from 15 mg at baseline to 2 mg at the end of the treatment and 50% of the patients could completely withdraw CS. A significant decrease in absolute blood eosinophils was observed one month after benralizumab treatment compared to baseline. However, there were no significant differences in lung function, BVAS score, and quality of life questionnaire after benralizumab treatment [58]. Overall, this pilot study suggests that benralizumab safely reduces systemic CS dose and EGPA exacerbations in subjects with refractory and CS-dependent EGPA.

The use of benralizumab has significantly reduced total peripheral blood eosinophil counts and, in some cases, MPO-ANCA negativity [44], biomarkers that may predict disease prognosis. However, these benefits need to be evaluated in further randomized clinical trials.

Several clinical trials with Benralizumab are currently underway: benralizumab in the treatment of eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (BITE, NCT03010436) [59], and efficacy and safety of benralizumab in EGPA compared to mepolizumab (MANDARA, NCT04157348) [60]. A summary of all relevant studies with benralizumab can be found in Table 2.

Benralizumab therapy in patients with EGPA

| Reference | Study design | Number of patients | Dose and route of administration | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Takenaka et al. [44], 2019 | Case report | 1 | 30 mg SC | Blood eosinophil normalizationClinical remissionCS reductionMPO-ANCA negativation |

| Padoan et al. [56], 2020 | Case series | 5 | Initial 3 doses: 30 mg SC every 4 weeksMaintenance dose: 30 mg SC every 8 weeks | 3 Patients completely withdraw from CSComplete depletion in blood eosinophilsACT improvementNo statistically significant difference in lung functionLack of improvement in ANCA-status |

| Nanzer et al. [57], 2020 | Case series | 11 | Initial 3 doses: 30 mg SC every 4 weeksMaintenance dose: 30 mg SC every 8 weeks | CS reductionComplete depletion in blood eosinophilsBVAS improvementNo statistically significant difference in lung functionACT improvementQuality of life improvement |

| Guntur et al. [58], 2021 | Prospective open-label pilot study | 10 | Initial 3 doses: 30 mg SC every 4 weeksMaintenance dose: 30 mg SC every 8 weeks | Benralizumab was well tolerated50% Of the patients could completely withdraw from CSSignificant decrease in absolute blood eosinophilsNo significant differences in lung function, BVAS, and quality of life |

Reslizumab

Reslizumab is an IgG4k humanized, mAb against IL-5 with a high IL-5-binding affinity, reducing eosinophil proliferation and airway inflammation approved for the treatment of severe eosinophilic asthma [12, 61].

A cohort of 9 patients [62] with oral CS-dependent EGPA and severe eosinophilic asthma were treated with reslizumab (3 mg/kg every four weeks). After 48 weeks of treatment, all patients achieved ≥ 50% maintenance oral CS reduction; even two patients could completely stop CS intake. This study observed that the oral CS reduction did not increase the peripheral eosinophil count. No significant changes were observed in pulmonary function and the BVAS [62].

Subsequently, an open-label pilot study evaluated the safety and efficacy of IV reslizumab (3 mg/kg every four weeks) in 10 subjects with MPO-ANCA negative EGPA. After 24 weeks of treatment, reslizumab was safe and well tolerated, and a reduction in oral CS intake was achieved in most of the participants [63]. The results from this study are similar to findings from other anti-IL-5 agents.

These studies suggest that reslizumab is a therapeutic option in EGPA patients with concomitant severe eosinophilic asthma and could help to reduce the use of CS [62, 63]. However, no significant improvement in overall BVAS scores was seen, suggesting that reslizumab may be less effective in controlling extrapulmonary manifestations in EGPA [62], but further studies are needed.

A summary of all relevant studies with reslizumab can be found in Table 3.

Reslizumab therapy in patients with EGPA

| Reference | Study design | Number of patients | Dose and route of administration | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kent et al. [62], 2020 | Case series | 9 | 3 mg IV/kg every 4 weeks | CS reduction2 Patients completely withdraw from CSNo significant changes were observed in BVAS and lung function |

| Manka et al. [63], 2021 | Prospective open-label pilot study | 10 | 3 mg IV/kg every 4 weeks | Reslizumab was safe and well toleratedCS reductionNo significant change in the asthma quality of life questionnaireDecrease in blood eosinophil countImprovement in BVAS |

Omalizumab

Omalizumab is a recombinant humanized anti-IgE mAb which binds selectively to the Cε3 domain of the crystallizable fragment (Fc) fragment of the heavy chain of free IgE, thus preventing its interaction with the IgE receptors found on the surface of mast cells, basophils, eosinophils, and B cells, preventing its degranulation thus reducing the inflammatory activation cells and pro-inflammatory factors [64, 65].

Several studies with omalizumab have been published over the years with promising and beneficial results in the treatment of eosinophilic allergic asthma and it is therefore believed that it may also be considered an effective therapy in the treatment of patients with EGPA, particularly in those patients with uncontrolled asthma symptoms. Unfortunately, experience with omalizumab in the treatment of EGPA is limited to single case reports [66–70] or case series only [12]. Most of these cases describe an improvement in asthma symptoms, nasal polyposis, and reduction in blood eosinophil counts [66, 67, 69, 70].

In 2016, Jachiet et al. [71] reported a nationwide retrospective study of 17 patients with relapsing and/or refractory EGPA treated with at least one dose of omalizumab. They suggested that in EGPA patients with asthmatic and/or sinonasal manifestations, omalizumab may have an uncertain CS-sparing effect in these patients [71]. However, the high risk of severe EGPA flares, possibly due to the reduction in the CS dose, questioned the use of omalizumab for treating EGPA [71].

Subsequently, another single center reported its experience of 18 patients with EGPA treated with omalizumab. They concluded that omalizumab worked as a CS-sparing agent in all patients. and reduced asthma exacerbations. However, no decrease in the eosinophil count during treatment was observed [72]. Some of the studies mentioned above can be found in Table 4.

Omalizumab therapy in patients with EGPA

| Reference | Study design | Number of patients | Dose and route of administration | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Giavina-Bianchi et al. [66], 2007 | Case report | 1 | 300 mg SC every 2 weeks | Improvement of asthmaBlood eosinophil reduction |

| Pabst et al. [67], 2008 | Case report | 2 | Doses adjusted to weight and IgE levels | Blood eosinophil count normalizationImmunosuppressive treatment was stopped |

| Lau et al. [68], 2011 | Case report | 1 | Doses adjusted to weight and IgE levels | Exacerbation when CS was taperedNo clinical or radiological improvement |

| Jachiet et al. [71], 2016 | Retrospective multicentre study | 17 | Doses adjusted to weight and IgE levels | Mild efficacy for treating asthma, ear, nose, and throat (ENT) symptomsCS reductionBVAS improvementBlood eosinophil count did not decreaseEGPA flares, possibly due to the reduction in the CS dose |

| Caruso et al. [70], 2018 | Case report | 1 | 450 mg SC every 2 weeks | Lung function improvementACT and quality of life questionnaire improvementBlood eosinophil counts reductionCS reduction |

| Celebi Sozener et al. [72], 2018 | Retrospective chart review | 18 | Doses adjusted to weight and IgE levels | 10 Patients responded completelyCS reductionExacerbation reductionforced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) improvementNo decrease in blood eosinophil count |

Paradoxically some case reports describe an association between the use of omalizumab and the onset of EGPA after withdrawal of oral CS [73–77]. These findings may hinder the use of omalizumab for the treatment of EGPA [71].

Omalizumab may be effective as a CS-sparing agent in EGPA with severe allergic asthma. Still, there is little evidence of improvement in extrapulmonary manifestations [65], but many more high-quality studies are needed.

RTX

RTX is an anti-CD20 chimeric mouse-human mAb. It induces B-cell depletion in peripheral blood [9, 78, 79]. Currently, it is licensed in Europe for rheumatoid arthritis and in severe ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV) [78] with an acceptable safety profile and is currently approved by the EMA and FDA as drug remission induction therapy in these patients [79–82]. However, in the pivotal trials with RTX performed in patients with AAV [80–82], patients with EGPA were excluded because this vasculitis is less frequent than other AAV [79].

The evidence of RTX benefits in patients with EGPA is limited to case series and small-sized [83–88], open-label studies on refractory/relapsing EGPA [9, 89].

In 2011, a prospective single-center, open-label pilot study with 3 patients using RTX (375 mg/m2 every 4 weeks) for induction of remission in refractory/relapsing EGPA patients with renal involvement was conducted. All patients were ANCA-positive and were followed up for 1 year and all of them achieved renal remission within the first 3 months [89].

A single-center cohort of 9 patients with refractory or relapsing EGPA treated with RTX was published [85]. After 3 months of RTX treatment, all patients had responded, with one patient being in complete remission. After a mean follow-up of 9 months, C-reactive protein concentrations had normalized, peripheral blood eosinophils count decreased, and CS had been reduced in all patients. Within the 9 months observation period, no relapses were recorded [85].

A cohort of 41 patients with EGPA treated with RTX between 2003 and 2013 was subsequently reported. They included new-onset, refractory, and relapsed diseases [83]. At 6 months, 83% of the patients improved, with remission achieved in 34% of them. CS was reduced in all patients and ANCA-positivity at baseline was associated with a higher remission rate [83]. B-cell depletion occurred in all patients. However, there were no differences in eosinophil counts.

Another cohort of 69 patients with refractory EGPA was studied and treated with RTX [87]. Response to treatment was achieved in 40.6% of patients by 6 months and this rose to 77.3% by 24 months. No differences according to ANCA-status were reported. RTX permitted prednisolone dose reductions. However, there were no changes with RTX treatment in the C-reactive protein and peripheral eosinophil counts [87].

Some of the clinical trials that are currently being conducted with RTX are RTX in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (REOVAS, NCT02807103) [90] and maintenance of remission with RTX vs. azathioprine for newly-diagnosed or relapsing eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (MAINRITSEG, NCT03164473) [91].

Despite the promising results of the studies described above, further prospective, randomized trials evaluating the use of RTX in EGPA are warranted. A summary of all relevant studies with RTX can be found in Table 5.

RTX therapy in patients with EGPA

| Reference | Study design | Number of patients | Dose and route of administration | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cartin-Ceba et al. [89], 2011 | Prospective open-label pilot study | 3 | 375 mg/m2 every 4 weeks | All patients achieved renal remission |

| Thiel et al. [85], 2013 | Single-center cohort of patients | 9 | No recorded | CS reductionBVAS reductionC-reactive protein normalizedReduction in blood eosinophil countsNo relapses had been recorded |

| Mohammad et al. [83], 2016 | Cohort of patients | 41 | 375 mg/m2 every 4 weeks (n = 10)2 doses 1,000 mg (n = 30) | 34% Of the patients achieved remissionCS reduction in all patientsANCA-positivity at baseline was associated with a higher remission rate at 12 monthsNo differences in eosinophil counts |

| Teixera et al. [87], 2019 | Cohort of patients | 69 | - | No differences in treatment response according to ANCA-statusCS reductionsNo changes in blood eosinophil counts |

-: blank cell

Anti-complement agents

Studies involving murine models have shown that activation of complement is critical in the pathophysiology of AAV and ANCA-activated neutrophils may activate complement and produce complement component 5a (C5a), these mechanisms may contribute to a worsening of respiratory symptoms [92, 93]. Other murine models have reported that C5-deficient mice and those lacking a C5a receptor (C5aR) did not develop AAV [94, 95] and concluded that blocking the C5aR with a small molecule may improve disease severity.

It was shown in a case report that an anti-C5 antibody (eculizumab) improved renal function [96] and a recent review reported that replacement of CS with a C5aR inhibitor, called avacopan is already a new therapeutic option that may decrease the CS intake and could improve the long-term outcome of patients with AAV. However, most studies are in murine models, and more clinical trials are needed [97].

Conclusions

EGPA remains a challenge for clinicians because the current gold standard treatments, CS and immunomodulators, do not always control symptoms and are often associated with significant morbidity. However, as a rare orphan disease, testing new therapies is challenging because few centers have sufficient numbers of patients to conduct randomised placebo-controlled trials.

Like patients with asthma, it is recommended to must phenotype and endotype patients with EGPA to offer them the best therapeutic alternative. Although there have been great advances in the treatment of EGPA since mepolizumab has been approved by the FDA and the ongoing trials with the new biologic therapies can hopefully be a promising tool for refractory/recurrent EGPA, further studies are needed to demonstrate the long-term efficacy of these novel biologic therapies.

Abbreviations

| AAV: |

antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies-associated vasculitis |

| ACR: |

American College of Rheumatology |

| ACT: |

asthma control test |

| ANCA: |

antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies |

| BVAS: |

Birmingham vasculitis activity score |

| C5a: |

complement component 5a |

| C5aR: |

complement component 5a receptor |

| CS: |

corticosteroids |

| EGPA: |

eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis |

| FDA: |

Food and Drug Administration |

| FFS: |

Five Factor Score |

| IL-5: |

interleukin-5 |

| ISAs: |

immunosuppressive agents |

| IV: |

intravenous |

| mAb: |

monoclonal antibody |

| MPO: |

myeloperoxidase |

| RTX: |

rituximab |

| SC: |

subcutaneous |

Declarations

Author contributions

ACH: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. CP: Conceptualization, Investigation, Visualization, Writing—review & editing. GP: Validation, Writing—review & editing, Supervision. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2023.