Abstract

Recent anti-cancer strategies are based on the stimulation of anti-tumor immune reaction, exploiting distinct lymphocyte subsets. Among them, γδ T cells represent optimal anti-cancer candidates, especially in those tissues where they are highly localized, such as the respiratory or gastrointestinal tract. One important challenge has been the identification of stimulating drugs able to induce and maintain γδ T cell-mediated anti-cancer immune response. Amino-bisphosphonates (N-BPs) have been largely employed in anti-cancer clinical trials due to their ability to upregulate the accumulation of pyrophosphates that promote the activation of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. This activation depends on the butyrophilin A family, which is crucial in contributing to Vγ9Vδ2 T cells stimulation but is not equally expressed in all cancer tissues. Thus, the clinical outcome of such treatments is still a challenge. In this viewpoint, a critical picture of γδ T cells as effective anti-cancer effectors is designed, with a specific focus on the best immune-stimulating therapeutic schemes involving this lymphocyte subset and the tools available to measure their efficacy and presence in tumor tissues. Some pre-clinical models, useful to measure γδ T cell anti-cancer potential and their response to stimulating drugs, therapeutic monoclonal antibodies, or bispecific antibodies are described. Computerized imaging and digital pathology are also proposed as a help in the identification of co-stimulatory molecules and localization of γδ T cell effectors. Finally, two types of novel drug preparation are proposed: nanoparticles loaded with N-BPs and pro-drug formulations that enhance the effectiveness of γδ T lymphocyte stimulation.

Keywords

Butyrophilins, zoledronic acid, amino-bisphosphonates, 3D modelsIntroduction

Since their first description in the early eighties, gammadelta (γδ) T lymphocytes have been proposed as useful tools in immunotherapy due to some peculiar characteristics [1]. First, they can start activation through their T cell receptor-independent major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-mediated antigen presentation. Second, they are deeply involved in stress responses to injury, infections, or neoplastic transformation. Third, their anatomical distribution is preferentially confined to epithelial and mucosal tissues. The main γδ T cell subset in the blood is the Vγ9Vδ2 (3–5% of circulating T lymphocytes), while the subset bearing the Vδ1 chain represents < 1–2% of T lymphocytes and is primarily present in the mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue [1, 2]. Vδ2 T lymphocytes recognize unprocessed non-peptide molecules, including phosphoantigens (PAgs) derived from the mevalonate pathway in mammalian cells and via the Rohmer pathway in bacterial cells [3].

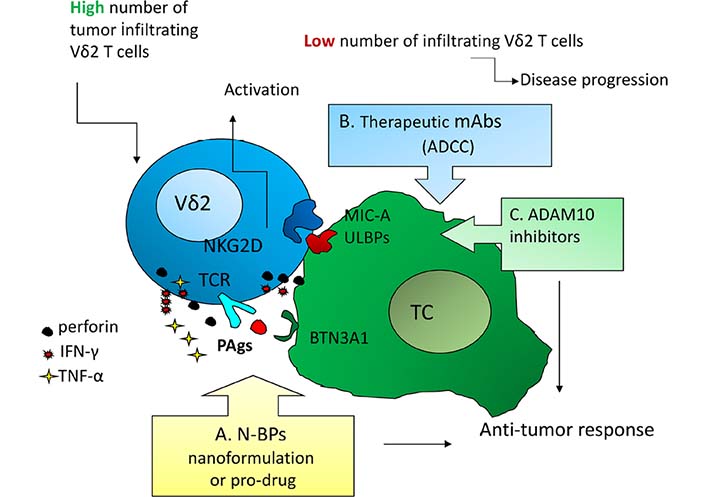

Molecules overexpressed at the surface of infected or tumor cells, such as MHC class I related genes-A (MICA) or MICB and UL16 binding protein (ULBP), can also bind to γδ T cells [4]. Ligation of these molecules by the natural killer group 2 member D (NKG2D) receptor leads to rapid and strong activation of γδ T lymphocytes that become very effective cytotoxic cells [4, 5]. Activation can also be elicited via Fc gamma receptor (FcγR) IIIa/CD16 that, upon interaction with the Fc of immunoglobulin G (IgG), initiates the antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), making this cell population a useful effector of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs)-based therapy [6]. Once activated, γδ T cells can proliferate and produce pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α); furthermore, they acquire and exert a strong cytotoxic ability against a large variety of tumor cell targets [1, 7]. For this unconventional antigen recognition, peculiar tissue localization, and multiple activation pathways, γδ T lymphocytes are antitumor effector cells both in solid tumors and leukemias or lymphomas, and are potentially suitable tools for anticancer therapy [7, 8].

How to achieve efficient anti-cancer γδ T lymphocytes

The anti-cancer function of γδ T lymphocytes has been primarily ascribed to the high production of PAgs, mostly isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP), abnormally accumulated in tumor cells due to unregulated mevalonate pathway [3]. Synthetic pyrophosphate-containing compounds, such as IPP and its isomer dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP) or bromohydrin pyrophosphate (BrHPP), can be used to expand γδ T cells and improve their anti-cancer properties (Figure 1) and have been proposed for cancer immunotherapy [7, 9, 10]. Amino-bisphosphonates (N-BPs), such as alendronic (Ale), pamidronic (Pam), and zoledronic (Zol) acid, are analogues of inorganic pyrophosphate and inhibit the farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase (FPPS) of the mevalonate pathway up-regulating IPP and DMAPP accumulation in neoplastic cells. This mechanism leads to the activation of Vδ2 T cells that proliferate and exert anti-tumor activity [10, 11].

Activation mechanisms as possible points of therapeutic intervention to trigger anti-tumor γδ T effector cells. A: N-BPs, either soluble or nanoformulated or as pro-drugs, to induce PAgs accumulation, BTN3A1/2 conformational changes, and T cell receptor-mediated activation of Vδ2 T cells [10–13]; B: therapeutic mAbs to trigger γδ T cell-mediated ADCC [1, 2]; C: a disintegrin and metalloproteinase 10 (ADAM10) inhibitors to up-regulated “stress-inducible” molecules and activate γδ T cells through the NKG2D receptor [6, 14]. These approaches should be efficient mainly when a high number of γδ T cells, mainly the Vδ2 subset that recognizes PAgs [2, 3], infiltrate the tumor. BTN3A: butyrophilin 3A; TC: tumor cell; TCR: T cell receptor

Although free of MHC-restriction, to recognize IPP Vδ2 T cells needs the help of molecules necessary for the binding and presentation of phosphates to γδ T cell receptor (Figure 1) [12, 13]. Such proteins belong to the BTN3A (CD277) family, structurally related to B7 co-stimulatory molecules, composed of three isoforms: BTN3A1, BTN3A2, and BTN3A3, bearing two extracellular immunoglobulin domains, a transmembrane region and all, but BTN3A2, an intracellular signaling domain, named B30.2. Only the B30.2 domain of BTN3A1, due to a positively-charged pocket, can bind PAgs inducing conformational changes of extracellular BTN3A1 and its consequent membrane stabilization [12]. Recently, other members of the BTN3A family, including BTN3A2 and BTN2A [15, 16], have been shown to participate in γδ T cell activation, enlarging the spectrum of co-stimulatory molecules useful to enhance PAgs-induced anti-tumor response.

Activation of γδ T cells through the recognition of stress-related antigens (including MICA/ULPBs) by the NKG2D receptor, is less exploited for anti-cancer purposes. Nevertheless, in Hodgkin lymphomas we demonstrated that inhibitors of the ADAM10 enhance in vitro the expression of NKG2D-ligands on lymphoma cells, leading to γδ T cell activation, cytokine production, and release of cytolytic enzymes [14]. This mechanism can operate both in epithelial tumors and in hematological malignancies, representing an additional tool targetable for therapeutic purposes (Figure 1).

Pros and cons of γδT cells as anti-cancer tools

Tumor infiltrating γδ T lymphocytes have been found in several cancers and their presence at the tumor site is described as a favorable prognostic factor [17]. This might overcome one of the major constraints on the application of γδ T cells in anti-cancer immunotherapy, related to the difficulties of their ex vivo expansion. In turn, direct in vivo stimulation with N-BPs has to face the preferential localization of these compounds in the bone [11].

Based on these considerations, γδ T cell-mediated immunotherapy can be classified according to the way to get anti-cancer effectors, namely in vivo or ex vivo stimulation. Direct in vivo stimulation with Zol has been described in metastatic-refractory prostate cancer, with a significant correlation between T cell increase and favorable clinical outcome [9]. A pilot study, published in 2003 by Wilhelm et al. [8], reported that the administration of Pam in Hodgkin lymphoma and melanoma patients achieved partial response in the majority of patients after infusion of interleukin-2 (IL-2). Since then, both Zol and Pam were extensively used in several clinical trials [18–21], in solid tumors and hematological malignancies, showing a good expansion of γδ T cells but controversial or disappointing clinical outcomes and adverse reactions, mainly referred to IL-2 administration. As an alternative, synthetic PAgs, such as BrHPP, have been used in Phase I clinical studies with the same alternating results and adverse reactions [10, 18–20].

The second type γδ T cell immunotherapy depends on the ex vivo stimulation of this cell population with PAgs or N-BPs, followed by the adoptive transfer of effector cells.

This therapeutic scheme, however, could not avoid IL-2-related adverse effects; moreover, in a number of patients, reinfused activated effectors remained in the bloodstream and did not reach the tumor site, raising the proposal for local administration to improve the effector/target ratio [18].

Another constrain may be the expression level of BTN3A at the tumor site: we showed that ex vivo stimulation of γδ T lymphocytes by Zol in colorectal cancer (CRC) patients is partially related to BTN3A1 expression by tumor cells, both isolated and inside the tumor tissue [22]. So far, it is not fully defined which BTN3A isoform is the best co-stimulating/PAgs-presenting molecule to optimize the recognition and expansion of γδ T effector cells. Whatever the isoform of BTN3A is potentially crucial for an effective PAgs-induced anti-tumor response, histological evaluation of the expression levels of these molecules and site-specific localization of γδ T lymphocytes may help to predict the outcome of N-BPs related immunotherapy. The recent development of imaging software and digital technology allows the extensive analysis of tumor specimens to achieve this purpose, opening the field of the so-called digital pathology [22].

Additional disadvantages to be considered are the presence in the tumor tissue of cytokines with immunosuppressive effects, such as IL-4, IL-17, IL-10, transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), and IL-9, able to reduce or even neutralize the anti-tumor effects of γδ T cells [1, 2, 10]. Among them, TGF-β has been found to counteract several effector functions of Vδ2 T cells activated by N-BPs or via NKG2D upon target exposure to ADAM10 inhibitors [10, 14]. Also, activated γδ T cells transiently upregulate different inhibitory receptors, including programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1), cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4), T cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains (TIGIT), T cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3 (Tim-3), and CD39, which may lead to auto-regulation or inhibit the function of αβ T cells [10]. In turn, γδ T cells are also susceptible to regulation and inhibition of their function inhibition by Treg cells, thus limiting the intensity or duration of anti-tumor response [10, 11].

Finally, the tumor microenvironment, especially mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC), can influence the final efficiency of effector cell activation: this environment can down- or up-regulate anti-tumor effector functions through the action of chemo-cytokines, inflammatory mediators, and matrix remodeling factors [18]. In our previous experience, N-BPs can overcome the down-regulation exerted by MSC: in CRC Zol induces MSC expressing BTN3A1 to stimulate autologous γδ T cells, while in Hodgkin lymphoma prevents the inhibitory effects exerted by lymph node MSC on anti-tumor Vδ2 T cells [22, 23].

Improve stimulation of anti-cancer γδ T cells

A major drawback of N-BPs-based immunotherapy is represented by their rapid clearance from the circulation due to specific bone tropism [24]; this implies that N-BPs do not reach the tumor site easily so that activation of Vδ2 T cells can barely occur inside the tumor upon systemic administration [24]. Encapsulation of N-BPs in liposomes (L) has been reported to increase the level of N-BPs at sites other than bone: upon intravenous administration of liposome preparations of either Zol or Ale (L-Zol, L-Ale) high concentrations were found in the lung, liver, and spleen [25]. Both L-Ale and L-Zol could trigger Vγ9Vδ2 T cells to produce IFN-γ and kill tumor target cells, but the therapeutic index was not always higher than that of free N-BPs [25]. As an alternative, N-BPs encapsulated in pegylated nano-particles, could reduce the growth of solid carcinomas, bone primary tumors, and metastasis and increase their localization in the tumor [25].

The delivery of nanoformulated N-BPs can also exploit the enhanced permeation and retention (EPR) effect, due to the presence of large vessel fenestrations and triggered by the absence of lymphatic drainage at the tumor site, with the further concentration of the drug [26]. We have recently reported that Zol encapsulated in spherical polymeric nanoparticles, composed of poly(D, L-lactide-co-glycolic) acid (PLGA), 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC), and 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-polyethylene glycol (DSPE-PEG) is very efficient in expanding Vδ2 T cells, from both peripheral blood and neoplastic mucosa of patients suffering from CRC, at a concentration about 300-fold lower than free Zol [26].

Recently, a novel bisphosphonate prodrug, tetrakis-pivaloyloxymethyl 2-(thiazole-2-ylamino) ethylidene-1,1-bisphosphonate (PTA), has been reported to induce the accumulation of both IPP and DMAPP and efficiently expand peripheral Vγ2Vδ2 T cells with anti-tumor activity [27]. PTA is 2–300-fold more effective than soluble Zol and is suitable for both ex vivo and in vivo therapeutic applications. These results open a new conceivable strategy in the therapeutic use of N-BPs for anti-cancer purposes.

As already achieved with αβ T lymphocytes, chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cells have also been described for γδ T cells, targeting CD19 on leukemic cells or the ganglioside D2 in neuroblastoma [20]. However, CAR-T cell-based immunotherapy is still burdened by severe problems such as cytokine storm or high recurrence rate in solid cancers [19, 20].

Last but not least, the option to exploit ADCC has to be taken into consideration (Figure 1). The combination of therapeutic antibodies, such as the anti-human epidermal growth factor-2 (HER2) trastuzumab in breast cancer or the anti-CD20 rituximab in lymphoid malignancies, with adoptive transfer of γδ T cell, activated ex vivo with BrHPP was proven to enhance the efficacy of both healing arms [10, 19]. This combination therapy can also be strengthened by immune checkpoint inhibitors, including the anti-PD-1 pembrolizumab: this strategy seems to reinforce cytokine production rather than cytolytic activity [10, 19]. Another interesting approach is the use of bispecific antibodies directed against a tumor antigen, e.g., the HER2 or the epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM), and Vγ9, resulting in a functional bridge that helps the targeting of effector T lymphocytes to tumor cells [19]. Finally, ADAM10 inhibitors may be proposed as an additional tool for combined immunotherapy based on the up-regulation of “stress-induced” molecules, leading to anti-tumor effector cell activation through NKG2D receptor (Figure 1) [14].

Detect and test anti-cancer γδ tumor infiltrating lymphocytes

Due to the complexity of cellular and soluble factors conditioning the outcome of γδ T cell immunotherapy, pre-clinical evaluation of innovative therapeutic schemes should be extensive, careful, and precise. However, animal models are not fully appropriate: indeed, human γδ T cell subsets have no counterpart in mice or other experimental animals [1, 10, 14, 15]. In addition, when human neoplastic cells are injected into immunosuppressed animals to avoid the xenogeneic reaction, some side effects are not detectable and, even in humanized mice, the tumor microenvironment is complex and deeply different from humans [28]. In particular, lymph node architecture may not reach a complete development, thus impairing the generation of a fully functional human immune system, leaving B or T cells at an immature stage [29]. From this viewpoint, reliable and inexpensive in vitro pre-clinical models may help to achieve the purpose: in particular, three-dimensional (3D) culture systems, validated by the European reference laboratories for the selection of anti-tumor drugs, are now available. These include the model of tumor cell homotypic spheroids composed of a single cell type, more complex spheroids with tumor and MSC, and patient-derived organoids, generated from tumors and usually composed of tumor cells at a different stage of differentiation [28]. As an example, we reported that Zol triggers the Vδ2 T cells to kill CRC cells organized in spheroids: the degree of this response and the effectiveness of Zol is measurable by computerized imaging of these 3D cultures [30]. More recently, we published that Zol nano-constructs sensitized both CRC spheroids and patient-derived organoids to Vδ2 T cell-mediated killing, upon priming with a 20-fold lower amount compared to free Zol [26].

The advantages of the spheroid model are mainly related to feasibility, low cost, and reproducibility that allow a large number of experimental replicates; this model has been extensively used for anti-cancer drug testing [28]. However, tissue architecture is poorly represented, accessory cells populating the stroma are missing and the extracellular matrix does not conserve its complete structure, even in mixed spheroids where at least MSC are present. Instead, tumor-derived organoids are morphologically similar to the original small tumor, maintaining the basic features of the tissue. In CRC organoids we could demonstrate the infiltration of Zol-activated γδ T lymphocytes and follow their localization and function inside the micro-tumor after fluorescence labeling of the cells and microscopical analysis [22, 30]. On the other hand, the spheroid model allows the measurement and characterization of tumor physical properties, either related to the cyto/histotype or due to the effects exerted by activated γδ T lymphocytes, allowing a rough evaluation of infiltration as well [30, 31]. By the mean of a microfluidic device specifically designed to measure the weight, size, and mass density of CRC tumor spheroids, cell line-dependent differences can be documented and associated with the number of growing cells and the degree of spheroid compaction [31]. This system can also be used to measure variations due to effector-mediate cytotoxicity or drug-induced tumor-cell damage.

Another system to evaluate and measure tumor variations related to the action of effector lymphocytes is the computerized analyses of images acquired by confocal microscopy or by scanning of sections stained in immunohistochemistry. Sections can be obtained from the original tumor or a 3D culture model, either spheroids or organoids, subjected to anti-cancer drug treatment or challenged with stimulated effector lymphocytes [28]. These analyses may allow the definition of therapeutic schemes based on various combinations of stimulating drugs, such as N-BPs, mAbs, or immune check point inhibitors.

At the same time, systematic evaluation of BTN3A expression, or other stress-related or co-stimulatory molecules, and γδ T cell infiltration at the tumor site, by the mean of computerized imaging and digital pathology [22], should help to define the eligibility of patients suitable for direct or indirect stimulation of γδ T cell-mediated immunotherapy. Along this line, a recent report showed that Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, activated in vitro with Zol, in the presence of IL-2, IL-15, and vitamin C, prolong survival in a humanized mice model of lung cancer [32]. In the same report, transfer of allogeneic Vγ9Vδ2 T cells from a healthy donor activated in vitro as above, were used to treat 132 late-stage cancer patients, without significant adverse effects, further supporting the feasibility of adoptive immunotherapy based on N-BPs and Vγ9Vδ2 T lymphocytes.

Conclusions and perspectives

The unique immunological properties of γδ T lymphocytes, in particular tissue localization and MHC independent recognition of small antigens ubiquitous in many tumors, confirm their future development in anticancer immunotherapy, despite the results not being fully satisfactory obtained in the clinics so far. In the last years, scientists and physicians have gained huge experience in γδ T cell-based immunotherapy; starting from this knowledge, therapeutic schemes should be revised and optimized to get effective results in clinical practice. To this purpose, the development of high-throughput screening systems is needed, taking into account the failure to match γδ T cell populations in animals and humans, with the exception of the highly expensive non-human primate models.

In this perspective, 3D cultures have deeply contributed to improving the reliability of in vitro pre-clinical models in anti-cancer drug testing. In particular, co-cultures of cancer spheroids or organoids and immune cells have become a reproducible and informative strategy for the testing of cancer immunotherapy. These models also allow the evaluation of tumor microenvironment interference on anti-cancer effector functions.

In addition, computerized imaging and digital pathology would contribute to defining both biomarkers for tumor susceptibilities, such as BTN3A or NKG2D ligands expression levels, and the degree of γδ T cell infiltration at the tumor site; these parameters should help to select suitable patients and predict their response to immunotherapy. Finally, innovative formulations of drugs capable of stimulating γδ T lymphocytes, including prodrugs or nano-formulated compounds, should complete the improvement of these anti-cancer strategies.

Abbreviations

| ADAM10: | a disintegrin and metalloproteinase 10 |

| ADCC: | antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity |

| Ale: | alendronic acid |

| BrHPP: | bromohydrin pyrophosphate |

| BTN3A: | butyrophilin 3A |

| CRC: | colorectal cancer |

| DMAPP: | dimethylallyl pyrophosphate |

| IFN-γ: | interferon-γ |

| IL-2: | interleukin-2 |

| IPP: | isopentenyl pyrophosphate |

| L: | liposomes |

| mAbs: | monoclonal antibodies |

| MHC: | major histocompatibility complex |

| MICA: | major histocompatibility complex class I related genes-A |

| MSC: | mesenchymal stromal cells |

| N-BPs: | amino-bisphosphonates |

| NKG2D: | natural killer group 2 member D |

| PAgs: | phosphoantigens |

| Pam: | pamidronic acid |

| Zol: | zoledronic acid |

| 3D: | three-dimensional |

Declarations

Author contributions

Both AP and MRZ contributed conception and design of the article; MRZ wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Both authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

Some data described in this manuscript derive from studies supported by the Italian Association for Cancer Research (IG-17074 to MRZ; IG-21648 to AP).

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2022.