Abstract

Humans are afflicted by a wide spectrum of autoimmune disorders, ranging from those affecting just one or a few organs to those associated with more systemic effects. In most instances, the etiology of such disorders remains unknown; a consequence of this lack of knowledge is a lack of specific treatment options. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is the prototypic systemic autoimmune disorder; pathology is believed to be antibody-mediated, and multiple organs are targeted. Periods of disease “flares” are often followed by long periods of remission. The fact that SLE is more commonly observed in females, and also that it more particularly manifests in females in the reproductive age group, has quite naturally drawn attention to the potential roles that hormones play in disease onset and progression. This review attempts to shed light on the influences that key hormones might have on disease indicators and pathology. Databases (Google Scholar, PubMed) were searched for the following keywords (sometimes in certain combinations), in conjunction with the term “lupus” or “SLE”: autoantibodies, recurrent abortion, polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), preeclampsia, pre-term delivery, estrogens, progesterone, androgens, prolactin, leptin, human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). Cited publications included both research articles and reviews.

Keywords

Autoimmune diseases, systemic lupus erythematosus, sex steroids, prolactin, leptin, human chorionic gonadotropin, reproductive dysfunctionIntroduction

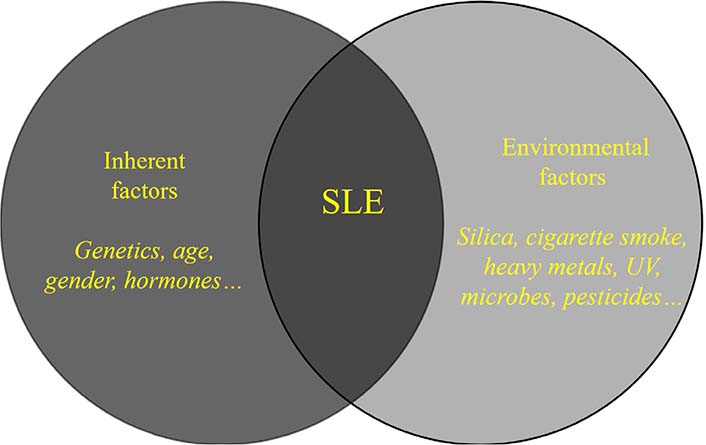

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE, or lupus) is a systemic autoimmune disorder that can affect many organs, including the skin, joints, the central nervous system, and the kidneys. With the exception of monogenic lupus, a complex interaction of inherent and environmental factors is believed to contribute to disease onset [1, 2]; some such factors are outlined in Figure 1.

A complex interaction between inherent and environmental factors is believed to contribute to the onset of SLE in most instances. UV: ultraviolet light

SLE is characterized by aberrant activation of the innate and adaptive immune systems, causing the accumulation of autoantibodies and inflammatory immune cells [3]. More than a hundred different autoantibody specificities have been described in lupus; ribonucleoproteins [for example, Smith (Sm), Ro, La], nucleic acids [for example, double-stranded DNA (dsDNA)], and lipids are often targeted [4]. While several of the antibody specificities observed in lupus have been documented in other autoimmune diseases as well, antibodies against dsDNA and the Sm protein are characteristic of lupus [5]. Interestingly, some common autoantibody specificities (such as anti-nuclear, anti-Ro, anti-La, and anti-phospholipid antibodies) can be detected in serum many years before clinical onset, whereas others (like anti-dsDNA and anti-Sm antibodies) appear closer to the appearance of overt disease [6]. Several investigations have revealed evidence for the association of anti-dsDNA autoantibodies with glomerulonephritis, one of the most serious consequences of the disease [7].

SLE predominantly affects women in their reproductive years [8], prompting investigations into the role reproductive hormones play in disease onset and progression. A higher incidence of premature ovarian failure has been observed in SLE patients [9, 10], the precise reasons for which remain unknown. Interestingly, patients with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) express many of the antibodies found in SLE patients [11], prompting speculation that PCOS could have an autoimmune etiology. Higher rates of preeclampsia have been observed in SLE patients [12, 13]. Several recent reports indicate that pregnancies in SLE patients are also characterized by a higher incidence of pre-term delivery [14, 15].

The presence of anti-Sjögren’s-syndrome-related antigen A (anti-SSA)/Ro and anti-SSB/La antibodies during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of neonatal lupus, a condition that arises due to transplacental autoantibody transport [16]. Autoantibodies of several specificities have been associated with recurrent abortion in SLE patients [17]. More particularly, the presence of anti-phospholipid antibodies is linked with recurrent pregnancy loss, fetal loss, and stillbirth in women with SLE [18, 19].

Hormones and SLE

Steroid hormones can have strong immune-modulatory effects, a fact that may explain, to an extent, the female preponderance of lupus. The effects of 17β-estradiol, testosterone, progesterone, dehydroepiandrosterone/dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate on disease incidence and severity have been described [20, 21]. Steroid hormones can potentially modulate the T-helper 1 (Th1)/Th2 cytokine balance. For example, progesterone causes Th2 polarization [22], and Th2-related cytokines [particularly interleukin-10 (IL-10) and IL-6] play major roles in the progression of lupus; levels of these cytokines are reportedly higher in SLE patients than in healthy individuals, and levels of IL-10 correlate with anti-dsDNA antibody titers [23].

Pregnancy presents a potentially high-risk condition for lupus, and pregnancy-associated disease flares have been reported [21, 24]. These observations are in line with data suggesting that pregnancy (at least notionally) is believed to constitute a Th1-to-Th2 immune skew and that autoantibodies constitute prime drivers of pathology in SLE. In normal pregnancies, levels of estrogens and progesterone progressively increase from the first trimester of pregnancy, reaching peak levels in the third trimester. Estrogens, at “physiological” levels, potentiate both Th1 and Th2 responses, whereas, at “supra-physiological” levels (such as those achieved in the third trimester), they suppress Th1 responses while promoting Th2 responses; such a milieu would favor the production of immunoglobulins. That said, while some studies describe heightened disease activity in the second trimester, there appears some discordance with levels of estrogens and progesterone [21].

Lupus-prone mice have been extensively employed to elucidate the roles hormones play in disease onset and progression, as well as the genes they might influence. For example, microarray analysis in intact male and female New Zealand black (NZB) × New Zealand white (NZW) F1 mice, as well as in gonadectomized mice with/without steroid supplementation, has revealed that estrogens and androgens can influence genes in a differential manner in the two sexes [25].

A role for pituitary hormones has also been envisaged. While most studies appear to suggest heightened luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels in male SLE patients, and LH levels in female patients [26], the relevance of these observations remains unclear. Evidence of the possible influence of gonadotropins on disease activity has been obtained in lupus-prone Swiss inbred (SWR) × NZB F1 mice; the administration of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonists to ovariectomized female mice enhances survival, while GnRH agonists drive autoreactive responses [27]. As described in more detail below, an abundance of data suggest a role for prolactin in autoimmune diseases in general, and in lupus in particular [28].

Estrogens

Dendritic cell-derived type 1 interferons (IFNs) are believed to drive lupus progression, and mechanistic links between estrogens and the IFN signature have been described [29].

Estrogens are generally considered to have immune-stimulatory effects. Besides being present in reproductive tissues, estrogen receptors (ERs, ERα and ERβ) are also widely expressed in most cells of the immune system, exerting influence on both innate and adaptive immune responses [30]. The role of ERs in lupus has been studied in various murine models of disease. Ovariectomized NZB × NZW F1 mice treated with the potent ERα agonist propyl pyrazole triol develop autoantibodies and proteinuria with enhanced kinetics. The ERβ agonist diarylpropionitrile, on the other hand, reduces levels of some immunoglobulin G (IgG) anti-dsDNA autoantibody subclasses but does not reduce total IgG, proteinuria, or mortality. These studies indicate that, while ERα signaling may have immune-stimulatory effects, ERβ signaling could be immunosuppressive, to an extent [31]. In line with this data, ERα deficiency has been shown to reduce autoantibodies levels and glomerulonephritis, and to improve survival in female and male NZB × NZW F1 mice [32]. Further, targeted deletion of ERα specifically in B cells leads to decreases in both the production of pathogenic autoantibodies and the development of nephritis in these mice [33]. Interestingly, a sex-dependent effect of ERα deficiency has been observed in lupus-prone mice [34].

Levels of ERα messenger RNA (mRNA) are heightened in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from SLE patients [35]. While T cells from SLE patients display numerous defects in homeostasis, phenotype, signaling, metabolism, and function [36], evidence suggests that estrogen could contribute to these outcomes [37], with receptor polymorphisms also exerting some influence [38]. That estrogen suppresses extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) phosphorylation in phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate + ionomycin-stimulated T cells from SLE patients with inactive or mild disease but not with moderate or active disease [39] is significant in light of the fact that downregulation of the ERK pathway is known to induce DNA demethylation [40], and DNA hypomethylation is a characteristic epigenetic aberration in SLE [41, 42].

Estrogen increases expression levels of the activation markers calcineurin and CD154 on T cells from women with SLE but not from healthy women, which is an indication of increased sensitivity of the former [43]. While estradiol tightly regulates calreticulin levels in T cells derived from healthy individuals, such control is lost in T cells from SLE patients, which is a fact that could contribute to abnormal T cell function [44]. Estradiol treatment of T cells from SLE patients (but not of healthy T cells) leads to increased expression of Fas ligand (FasL) and caspase-8, indicating that the steroid may induce cell death by activating the extrinsic pathway of apoptosis under appropriate conditions [45]. This is an observation of some significance, given that aberrant apoptosis has been implicated in lupus initiation and progression. Of particular relevance is the fact that apoptotic blebs contain endogenous toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands, some of which signal via TLR-7 and TLR-9; such signaling has been implicated in disease progression [46]. Stimuli that aid the processes that induce additional cell death would be expected to contribute to disease-driven pathological events, including effects on the reproductive system.

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-like weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK, a member of the TNF superfamily) is a proinflammatory, multifunctional cytokine which induces the release of several inflammatory mediators including IL-6, a cytokine associated with renal damage in SLE [47]. Treatment of PBMCs derived from patients of lupus nephritis with estrogen increases TWEAK mRNA levels, an effect negated by an ERα inhibitor (methyl-piperidino-pyrazole) or an ER antagonist (fulvestrant). Co-administration of TWEAK short hairpin RNA (shRNA) attenuates renal pathology and decreases serum IL-6 levels in estrogen-treated ovariectomized lupus-prone mice [48].

These studies indicate that estrogen plays important immune-modulatory roles in lupus, acting via several mediators to accelerate the disease course.

Prolactin

Hyperprolactinemia is observed in several autoimmune diseases and is believed to contribute to pathological outcomes [28]. Prolactin appears to participate in the pathogenesis of SLE by influencing both the innate and adaptive arms of the immune system. Hyperprolactinemia has been documented in 20–30% of SLE patients, and a correlation has been drawn between serum prolactin levels and disease activity. In particular, evidence suggests that prolactin plays a role in the pathogenesis of lupus nephritis, as well as in the neuropsychiatric, serosal, hematologic, articular, and cutaneous manifestation of the disease [49]. Increased levels of prolactin are observed in 12% of patients with the anti-phospholipid syndrome, and levels correlate with miscarriage in pregnant patients [50].

SLE patients express an increased frequency of the prolactin gene’s –1149 G allele; following incubation with phytohemagglutinin, SLE lymphocytes carrying the allele express enhanced prolactin mRNA levels [51].

Given that several pathologies in SLE are believed to be autoantibody-mediated, the fact that increases in serum levels of prolactin in SLE patients coincide with disease flares (with levels reducing upon disease remission), and also that prolactin levels correlate with serum levels of dsDNA antibodies [52], is clearly significant. While the prolactin receptor is expressed at higher levels on pro-B cells derived from lupus-prone mice [53], the full implications of this observation are at present unclear. In pregnant SLE patients, heightened levels of prolactin are linked with poor maternal-fetal outcomes [54]. Significantly, the presence of anti-prolactin antibodies (found in a certain percentage of SLE patients) correlates with lower disease activity in non-pregnant patients [55] and better outcomes in pregnant patients [56]. Further evidence of the pathological effects mediated by prolactin comes from the use of bromocriptine (a dopamine receptor agonist that blocks the release of prolactin) in lupus-prone mice and SLE patients; in pregnant SLE patients, bromocriptine reduces disease relapse, improves outcomes, and allows for the reduction in concurrent steroid administration [57].

Progesterone

Studies indicate that progesterone mediates immunological effects distinct from estradiol and testosterone [58]. Progesterone appears to counteract many of the effects of estradiol, thereby ameliorating the risk of lupus-like disease [59]. Some of these processes may be compromised in lupus; for example, inadequate estrogen-induced priming of progesterone receptors in the reproductive tissue of lupus-prone mice has been observed [60]. The fact that female SLE patients have lower levels of progesterone during ovulatory menstrual cycles [61] may also be a contributing factor.

Treatment of pre-morbid female NZB × NZW F1 mice with medroxyprogesterone acetate decreases circulating IgG2a anti-dsDNA antibody levels and the deposition of anti-DNA antibodies in the kidney [62]; though IgG1 anti-dsDNA antibodies reportedly increased in this study as well in other studies upon progesterone treatment, this isotype is considered less pathogenic in terms of its association with lupus nephritis [63].

In nuclear progesterone receptor knockout B6.Nba2 mice (C57BL/6 mice homozygous for the Nba2 autoimmunity locus), heightened levels of pathogenic class-switched IgG2c autoantibodies are observed, indicating that the steroid mediates protective effects [64]. However, other studies report that treatment of both male and female NZB × NZW F1 mice with progesterone leads to increased levels of serum anti-DNA IgG antibodies [65], while treatment with medroxyprogesterone has no beneficial effects [66].

Testosterone

It is believed that testosterone works to dampen the effects of lupus in both males and females. Low plasma levels of testosterone, androstenedione, dehydroepiandrosterone, and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate have been observed in female SLE patients, with concentrations inversely correlating with disease severity [67]. While the administration of testosterone-like anabolic steroids in women may induce a degree of disease amelioration [68], such treatment can be accompanied by undesirable, masculinizing side effects.

Of interest is the fact that hypogonadism in men is a risk factor for the development of SLE [69], and testosterone supplementation has been shown to be beneficial in some cases [70]. Autoantibody levels in SLE males correlate with specific polymorphisms of the androgen receptor [71]. In PBMCs isolated from SLE patients, testosterone reduces the generation of IgG antibodies (including anti-dsDNA autoantibodies), possibly via a suppressive effect on the production of IL-6 [72].

Several studies have described the beneficial effects of androgen supplementation in lupus-prone mice. Administration of testosterone to castrated mice of both sexes reduces levels of anti-DNA antibodies and glomerulonephritis and enhances survival; the benefits of androgen supplementation are evident in intact male mice as well [73]. Oral administration of dehydroisoandrosterone (another anabolic steroid) to female NZB × NZW F1 mice also reduces levels of anti-dsDNA antibodies and prolongs survival [74]. Some evidence suggests that the immunosuppressive and ameliorative effects of different androgens in NZB × NZW F1 mice may not be related to their endocrine properties [75].

Additional evidence in support of the idea that androgens play a protective role in lupus comes from observations that treatment of female lupus-prone mice with flutamide (an androgen receptor blocker) accelerates mortality [76].

Leptin

Leptin is secreted by adipocytes, the placenta, and the stomach, and is a sexually dimorphic cytokine/hormone, with its levels being higher in females. It regulates appetite and is believed to serve as a link between metabolism and immune function [77, 78]. Though not considered part of the classic reproductive hormonal axis, leptin exerts multiple influences on reproductive tissues. For example, it works to enhance levels of GnRH receptors in the pituitary, and also promotes granulosa cell and theca cell function in females, and testicular development in males [79]. It is proinflammatory in nature, and affects the survival, activation, differentiation, and function of T and B lymphocytes, and modulates autoreactive responses in many disease models [80].

While levels of leptin are higher in SLE patients than in healthy individuals [81], correlations with disease severity are not always apparent. An inverse correlation between the levels of serum leptin and androstenedione has been reported, indicating that leptin could contribute to the hypoandrogenicity observed in SLE patients [82].

Leptin levels in NZB × NZW F1 mice correlate with disease, and administration of leptin accelerates both autoreactivity and the onset of renal pathology. Conversely, the administration of anti-leptin antibodies ameliorates disease and enhances animal survival. The fact that leptin significantly inhibits Treg function probably contributes to its deleterious effect in these mice [83].

Anti-dsDNA antibody levels are lower in leptin-deficient lupus-prone mice; such mice also exhibit decreases in histological aberrations in the kidney [84]. Leptin deficiency also protects mice from the pristane-induced lupus-like disease [83].

Leptin induces the transcription of retinoid-related orphan receptor-γt (RORγt), thereby driving Th17 responses in humans and lupus-prone mice [85]. These findings assume importance given the fact that Th17 cells mediate inflammation and lupus-related pathologies [86].

Leptin, along with a high-fat diet, also promotes the development of lupus-associated comorbidities, specifically in NZB × NBW F1 mice; along with accelerated proteinuria, increased pro-inflammatory high-density lipoprotein scores, as well as atherosclerosis, are observed [87]. Correlating with these observations is the fact that leptin is associated with an increased risk of atherosclerosis in women with SLE [88].

Leptin enhances the phagocytotic uptake of apoptotic cells by macrophages and may therefore serve to increase the presentation of self-antigen to T cells [83, 89]. Further, it promotes the survival of autoreactive T cells in lupus-prone mice [90].

Data from both humans and mice, therefore, suggest that strategies targeting leptin could form the basis of new therapeutics in SLE.

Human chorionic gonadotropin

Case studies describe the occurrence of SLE in healthy women receiving ovulation-inducing agents which include human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) [91]. Further, ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS, a complication sometimes observed in women undergoing assisted reproductive techniques) has been linked with the use of hCG [92]; OHSS is characterized by thrombotic events (a pathology also observed in SLE), providing these observations relevance. Whether hCG-stimulated estradiol is subsequently responsible for OHSS is a matter of some debate [93].

Several pieces of additional evidence, albeit some indirect, suggest a possible role of hCG in the onset and/or progression of systemic autoimmunity. The presence of hCG in non-pregnant SLE patients, and also in male SLE patients has been observed [94]. Reports also suggest that pregnant SLE patients in the first trimester [95], as well as the second and third trimesters [96], exhibit significantly enhanced levels of serum hCG compared with healthy pregnant females. Heightened levels of hCG during pregnancy are associated with an increased risk of pre-eclampsia, an affliction associated with antiphospholipid syndrome and adverse pregnancy outcomes [97], which are pathological sequelae also associated with SLE.

Recent studies from our lab have shown that hCG specifically stimulates inflammation and autoimmune responses in non-pregnant, lupus-prone mice. Administration of hCG heightens global autoreactivity in these mice; titers of antibodies to dsDNA, as well as to several lupus autoantigens and phospholipids are enhanced, and animal survival is significantly compromised. Specifically, in splenic cell cultures from lupus-prone mice, hCG demonstrates synergistic effects with TLR ligands as well as with T cell receptor (TCR) stimuli; collectively, costimulatory markers on B cells are up-modulated and T cell proliferative responses are enhanced, as is the secretion of lupus-associated cytokines. In lupus-prone mice, these effects are specifically associated with the enhanced phosphorylation of the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase p38. Significantly, the addition of hCG along with either TLR ligands or anti-CD3 + anti-CD28 antibodies also significantly enhances the secretion of potentially pathogenic autoantibodies [98].

Though much remains to be discovered, evidence is strongly suggestive of the possibility that, counter to its described immunosuppressive/immunomodulatory effects in normal pregnancy [99], hCG drives, or is at least associated with, events that are known to precipitate lupus pathology.

Conclusions

The fact that several reproductive hormones significantly affect the clinical manifestation of SLE is now abundantly clear; sex and age both influence hormone-driven outcomes. That said, considerable challenges remain. While disease models either out of convenience or necessity frequently tend to be reductionist in nature, studying the influence of individual hormones in isolation and designing investigations that permit the appreciation of consecutive or concurrent hormonal cross-influences represents the next frontier. No doubt, enhanced understanding will lead to therapeutics with higher efficacy and diminished toxicity.

Abbreviations

| dsDNA: | double-stranded DNA |

| ERs: | estrogen receptors |

| GnRH: | gonadotropin-releasing hormone |

| hCG: | human chorionic gonadotropin |

| IgG: | immunoglobulin G |

| IL-10: | interleukin-10 |

| mRNA: | messenger RNA |

| NZB: | New Zealand black |

| NZW: | New Zealand white |

| OHSS: | ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome |

| PBMCs: | peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

| SLE: | systemic lupus erythematosus |

| Sm: | Smith |

| Th1: | T-helper 1 |

| TLR: | toll-like receptor |

| TWEAK: | tumor necrosis factor-like weak inducer of apoptosis |

Declarations

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the National Institute of Immunology, Aruna Asaf Ali Marg, JNU Complex (New Delhi, India) for digital access to online databases.

Author contributions

RS and RP wrote the manuscript which RP then edited.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by core grants of the National Institute of Immunology, Aruna Asaf Ali Marg, JNU Complex (New Delhi, India). The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2022.