Abstract

Aim:

Despite its high frequency of occurrence, mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI), or concussion, is difficult to recognize and diagnose, particularly in pediatric populations. Conventional methods to diagnose mTBI primarily rely on clinical questionnaires and sometimes include neuroimaging or pencil and paper neuropsychological testing. However, these methods are time consuming, require administration/interpretation from health professionals, and lack adequate test sensitivity and specificity. This study explores the use of BrainCheck Sport, a computerized neurocognitive test that is available on iPad, iPhone, or computer desktop, for mTBI assessment. The BrainCheck Sport Battery consists of 6 gamified traditional neurocognitive tests that assess areas of cognition vulnerable to mTBI such as attention, processing speed, executing functioning, and coordination.

Methods:

We administered BrainCheck Sport to 10 participants diagnosed with mTBI at the emergency department of Children’s hospital or local high school within 96 h of injury, and 115 normal controls at a local high school. Statistical analysis included Mann-Whitney U test, chi-square tests, and Hochberg tests to examine differences between the mTBI group and control group on each assessment in the battery. Significant metrics from these assessments were used to build a logistic regression model that distinguishes mTBI from control participants.

Results:

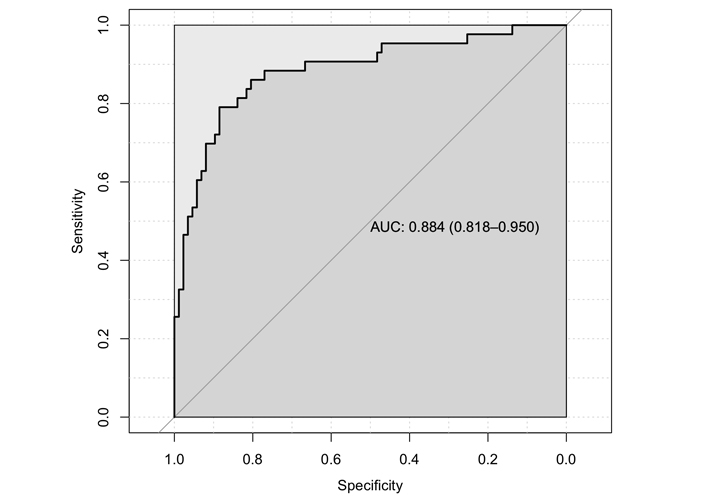

BrainCheck Sport was able to detect significant differences in Coordination, Stroop, Immediate/Delayed Recognition between normal controls and mTBI patients. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis of our logistic regression model found a sensitivity of 84% and specificity of 81%, with an area under the curve of 0.884.

Conclusions:

BrainCheck Sport has potential in distinguishing mTBI from control participants, by providing a shorter, gamified test battery to assess cognitive function after brain injury, while also providing a method for tracking recovery with the opportunity to do so remotely from a patient’s home.

Keywords

mTBI, concussion, BrainCheck, neurocognitive testingIntroduction

Mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI), or concussion, is an increasing public health concern not only due to its growing frequency of occurrence, but lack of guidelines and biomarkers that make diagnosis challenging [1]. This is particularly concerning in the pediatric population whose ongoing cognitive maturation makes them more vulnerable to head injury than the adult population [2]. The diagnostic utility of neuroimaging is limited, and current recommendations do not recommend routine imaging for mTBI unless otherwise clinically indicated [1]. Furthermore, literature evaluating sports-related mTBI has indicated that young athletes with mTBI may not recognize alarming symptoms due to a lack of awareness, understanding, or as a result of their cognitive impairment [3]. Thus, self-reported post-concussion symptoms are not reliable in this population. Additionally, while there are several concussion grading systems, there is little agreement between the systems on how they define and assess mTBI, and a collectively agreed gold-standard grading system does not exist [4]. Self-reporting concussion symptoms are often at odds with social pressures on a younger person to perform both educationally and athletically and place a strong bias making these measures more inaccurate [5].

Although neuropsychological tests were developed to more accurately measure cognitive deficits in mTBI, these tests have their limitations. Typically, they require a neuropsychologist or psychometrist to administer, score, and interpret the results of the battery of tests. More importantly, they lack adequate test sensitivity and specificity and are susceptible to practice effects that occur when tests are repeated more than once [6].

This study explores an alternative solution to address the barriers associated with mTBI assessment. The BrainCheck Sport Battery is a rapid, self-administered, and computerized neurocognitive test that assesses various areas of cognition, such as attention, processing speed, coordination, and executive functioning. Its diagnostic accuracy was previously validated as a testing method for traumatic brain injuries among adults, and it is classified as a diagnostic aid by the FDA [7]. However, the BrainCheck Sport Battery has not been explored for use in the detection of pediatric mTBI. Thus, the primary objective of this preliminary study is to assess the utility of BrainCheck Sport as a diagnostic tool for mTBI in the pediatric population.

Materials and methods

This study was approved by the Baylor College of Medicine institutional review board. Participant recruitment took place at the emergency department (ED) of Texas Children’s Hospital (TCH) in Houston, TX and Morton Ranch High School (MRHS) in Katy, TX. MRHS is a large local public high school with a diverse student population, multiple sports teams, and experienced staff assisting research. The recruitment period took place over one school semester at MRHS.

Study setting

Inclusion criteria

Participants were required to be:

Aged 8 to 18 years within the pediatric age range defined by the American Academy of Pediatrics [8].

Have corrected or perfect vision and hearing, and complete use of both hands.

Provided voluntary, written, informed consent to participate in the study.

Exclusion criteria

Participants meeting any of the following criteria were excluded:

Participants unable to follow directions appropriately for testing.

Participants with any history of traumatic brain injury, epilepsy, or neurological disorder, prior to the data collection/ED visit, as assessed by self-report.

Participants were categorized into the mTBI group if they received an official physician’s diagnosis of concussion or mTBI according to the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine (ACRM) criteria [9] during ED visit or recruitment at MRHS. Participants in the control group were interviewed for their history of traumatic brain injury, epilepsy, or neurological disorder, and those without these histories by the time of testing were eligible for the control group. At the end of the recruitment period, a total of 136 participants were approached and recruited, which included 126 participants in the control group and 10 participants in the mTBI group. Participants who did not meet inclusion criteria and met the exclusion criteria were not included in the study. In the end, we enrolled a total of 115 participants in the control group and 10 participants in the mTBI group.

Test administration

mTBI participants were administered Version 3 of the BrainCheck Sport Battery on the iPad within 96 h of injury by an ED nurse if recruited at TCH or by an athletic trainer if recruited at MRHS. Control participants, composed of MRHS athletes, were administered BrainCheck Sport by a research coordinator prior to the athletic season.

Test measures

A short description of each assessment that comprises the BrainCheck Sport Battery is listed in Table 1. A more detailed description provided of the battery has been described previously [7].

Neuropsychological assessments in the BrainCheck Sport Battery

| Assessment | Description | Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Flanker | We presented participants with a target arrow pointing to the left or right. The target was surrounded by congruent (> > > > >), or incongruent (<< > <<) arrows. Participants identified the direction of the target as quickly and accurately as possible. | Reaction time |

| Digit Symbol Substitution | Participants must match an arbitrary correspondence of symbols to digits; when presented with a new symbol, they input as quickly as possible the corresponding digit. | Cognitive processing |

| Stroop | Participants are instructed to find a word matching the given name of a color. There are two types of trials: CONGRUENT in which the word name and font color are the same (e.g., the word RED presented in red font), and INCONGRUENT in which the word name indicates a different color than the font (e.g., the word RED presented in green font). | Cognitive executive function |

| Trail Making | Participants are instructed to connect a set of 25 dots in their correct order as rapidly as possible. Trail Making Test A uses only numbers (1 through 25), while Trail Making Test B employs alternating letters and numbers (1 – A – 2 – B – 3 – C –…). | Visual attention and cognitive flexibility |

| Coordination | A ball is displayed on the tablet, moving according to the tilt of the tablet. A participant holds the tablet out in front at arm’s length and tilts it appropriately to keep the ball in a central circle. | Coordination ability |

| Immediate and Delayed Recognition | First, immediate recognition is measured by serially displaying 10 words, and then asking whether a word was just seen—either a distractor word or a target word (20 trials). At the end of the testing battery, without seeing the original list again, participants are again presented with 20 words and asked whether each word was presented before. | Memory |

Statistical analyses

Mann-Whitney U test was used to examine differences in age in the mTBI and control groups (Wilcoxon rank sum statistic W and P-value is reported), and a chi-square test was used to examine differences in sex between the two groups. Mann-Whitney U test was also used to compare groups on each assessment metric and the Hochberg test was used to adjust P-values for multiple comparisons. The most significant metrics from each assessment were used to generate a logistic regression model. Sensitivity and specificity of the overall battery was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses with a cutoff score that represented the maximum values sensitivity and specificity could reach. Data analysis was performed using the R statistical programming language in RStudio version 3.3.1.

Results

Demographics

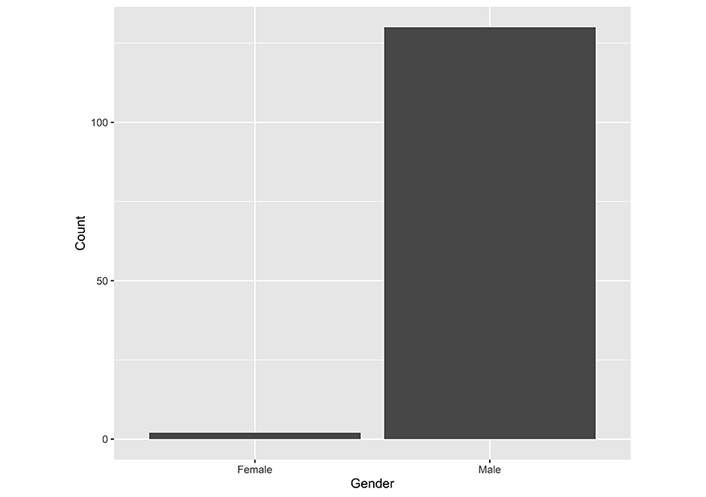

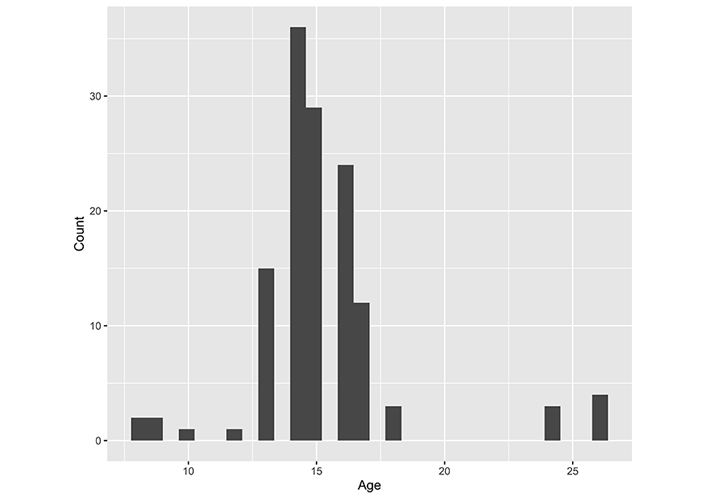

The overall sex distribution was unbalanced because most athletes participated in the study were males (Figure 1). Enrolled participant age ranged from 8 to 18 years, with a mean age of 14.7 and standard deviation of 1.6 (Figure 2). Nevertheless, there was no statistically significant difference in sex between the mTBI and control groups (χ2 = 0.005, P-value = 0.94). Similarly, no significant difference in age was detected between the mTBI and control groups (W = 499.5, P-value = 0.48).

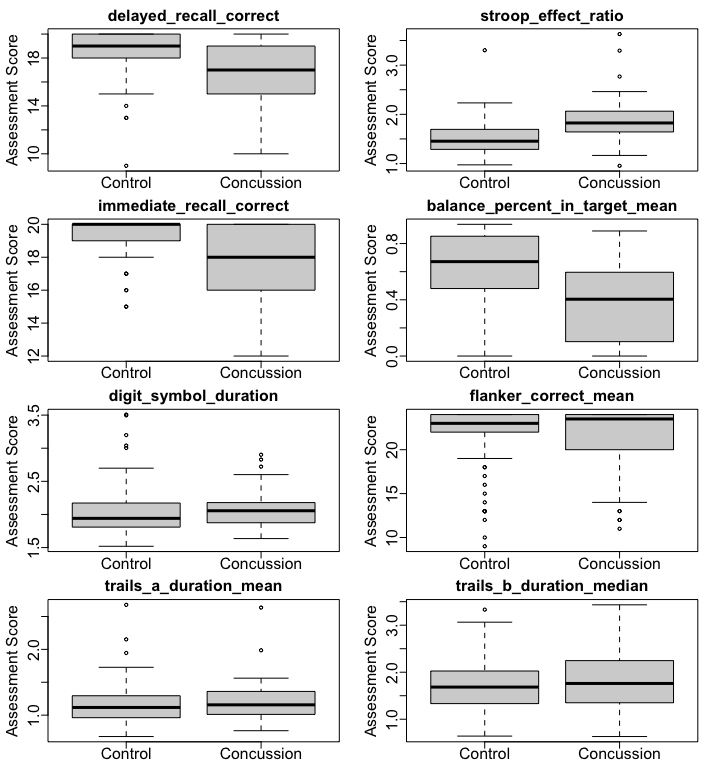

Assessments scores on mTBI

The BrainCheck Sport assessments evaluate different cognitive domains. As shown in Figure 3 and Table 2, we found that mTBI and control participants showed significant differences on raw scores of Delayed Recognition (P < 0.001), Immediate Recognition (P < 0.001), the Stroop test (P < 0.01), and the Coordination test (P< 0.001). In contrast, no significant differences were observed for the Trail Making test, the Flanker test, and the Digit Symbol Substitution test (Table 2).

Boxplots of BrainCheck Sport assessment metrics for the control group and the mTBI group

Mann-Whitney U test comparison between the mTBI and control groups on the BrainCheck Battery assessment metrics, with Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted P-values.

| Assessment | Metrics | Adjusted P-value | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coordination | balance_mean_distance_from_center | < 0.001 | Mean radial distance from center circle |

| balance_percent_in_target_mean | < 0.001 | Mean of percentage time in circle | |

| balance_position | < 0.001 | Mean position from the circle center | |

| balance_total_duration_in_circle | < 0.001 | Total duration time in circle | |

| balance_total_duration_out_circle | < 0.001 | Total duration time out of circle | |

| balance_total_duration_unpressed | 0.95 | Total duration time not pressing the screen | |

| balance_total_number_exits | 0.80 | Total number of times existing the circle | |

| Digit Symbol Substitution | digit_symbol_correct_per_second_mean | 0.80 | Mean of correct responses in a second |

| digit_symbol_duration | 0.10 | Total time taken to complete assessment. Time starts after digit display and ends when correct answer is completed | |

| Flanker | flanker_correct_mean | 0.28 | Mean of correct responses |

| flanker_reaction_time_central_mean | 0.87 | Mean reaction time of all correct responses in central cue trials | |

| flanker_reaction_time_congruent_mean | 0.51 | Mean of all reaction times when arrows point in same direction | |

| flanker_reaction_time_correct_mean | 0.87 | Mean reaction time of all correct responses | |

| flanker_reaction_time_correct_median | 0.93 | Median reaction time of all correct responses | |

| flanker_reaction_time_incongruent_mean | 0.95 | Mean of all reaction times when arrows point in opposite directions | |

| flanker_reaction_time_incorrect_mean | 0.28 | Mean reaction time of all incorrect responses | |

| flanker_reaction_time_spatial_mean | 0.83 | Mean reaction time of all correct responses in spatial cue trials | |

| Immediate and Delayed Recognition | delayed_recognition_correct | < 0.001 | Number of correct responses |

| immediate_recognition_correct | < 0.001 | Number of correct responses | |

| Stroop | stroop_basic_reaction_time_mean | 0.91 | Mean reaction time for neutral words |

| stroop_basic_reaction_time_median | 0.87 | Median reaction time for neutral words | |

| stroop_effect_ms_mean | < 0.001 | Mean reaction time incongruent - congruent (in ms) | |

| stroop_effect_ratio | < 0.001 | Median reaction time of incongruent / median reaction time of congruent | |

| stroop_reaction_time_congruent_mean | 0.006 | Mean reaction time for all correct answers in congruent trials | |

| stroop_reaction_time_incongruent_median | 0.057 | Mean reaction time for all correct answers in incongruent trials | |

| Trail Making | trails_b_duration_median | 0.98 | Median of response times between each click for TrailMaking B |

| trails_b_duration_mean | 0.80 | Mean of all response times between clicks for Trail Making B | |

| trails_a_duration_mean | 0.87 | Mean of all response times between clicks for Trail Making A |

Statistically significant P-values

These preliminary results demonstrate that participants who had an mTBI exhibited worse performance in BrainCheck Sport assessments of memory, executive, and coordination on the battery, which are consistent with results of golden standard neuropsychological tests [10–12]. In addition, they showed no significant deterioration in their cognitive performance and attention, which has also been observed in previous studies [13, 14].

Logistic regression

For the logistic regression model, 29 observations were deleted due to missing data in their Coordination assessment, therefore it utilized 86 of the participants in our control group and 10 of the participants in the mTBI group. We used “delayed_recognition_correct”, “stroop_effect_ratio”, “immediate_recognition_ correct”, “balance_percent_in_target_mean”, “digit_symbol_duration”, “flanker_correct_mean”, “trails_a_ duration_mean”, “trails_b_duration_median” as the metrics for our model. Based on the logistic regression model, the Stroop test, the Immediate Recognition test, the Coordination, and Trail-making tests were statistically significant at α = 0.05, while the rest were not statistically significant (Table 3). We performed a variance inflation factor (VIF) check, which showed no values greater than 2, rejecting the existence of collinearity in our model. Furthermore, the model residuals were checked and no influential outliers were present. We then performed ROC analysis methods to determine the optimal threshold for the logistic regression model that could maximize sensitivity and specificity in distinguishing between the control and mTBI groups. The ROC curve (Figure 4) had an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.884 (0.818–0.950, 95% CI). We found that the BrainCheck Sport Battery could achieve a sensitivity of 84% and a specificity of 81% when we chose 0.28 as the optimal decision threshold (Figure 4). In other words, if the model predicted probability for a participant is greater than 0.28, the participant is categorized to the mTBI group.

Summary of logistic regression results

| Assessment (metric) | β coefficient | β std. error | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coordination (balance_percent_in_target_mean) | –2.30 | 0.97 | 0.018 |

| Digit Symbol Substitution (digit_symbol_duration) | –1.93 | 0.89 | 0.03 |

| Immediate Recognition (immediate_recognition_correct) | –0.42 | 0.20 | 0.03 |

| Stroop (stroop_effect_ratio) | 2.86 | 0.83 | 0.0006 |

| Trail Making B (trails_b_duration_median) | 1.13 | 0.52 | 0.03 |

| Trail Making A (trails_a_duration_mean) | –0.75 | 1.04 | 0.83 |

| Delayed Recognition (delayed_recognition_correct) | –0.19 | 0.14 | 0.18 |

| Flanker (flanker_correct_mean) | 0.015 | 0.07 | 0.83 |

| Intercept | 9.40 | 4.61 | 0.04 |

Statistically significant P-values

Discussion

The findings of this study demonstrated that BrainCheck Sport was able to discriminate mTBI patients from the control group on some battery assessments and achieved decent levels of sensitivity (84%) and specificity (81%) when classifying mTBI, despite the small sample size of the mTBI population. This is achieved by evaluating the cognitive function, memory, and coordination of the participants under tests. These preliminary results reflect that BrainCheck Sport has potential as a diagnostic aid for pediatric mTBI, with similar accuracy as in the adult population [7].

Our results demonstrated that after mTBI, patients experienced deficits on Immediate and Delayed Recognition tests; Coordination tests; and the Stroop color tests which represent deficits in cognitive domains consisting of short-term memory, coordination, and executive function, specifically inhibition and attention, respectively. These are typical symptoms observed after sustaining an mTBI. However, mTBI patients were not observed to have diminished performance on Trail Making, Digit Symbol Substitution, or the Flanker tests which represent cognitive domains consisting of executive function, specifically, cognitive flexibility, information processing, and speed, and visual attention, respectively. As suggested by previous studies, not all cognitive domains are affected by mTBI [13, 14]. However, De Beaumont et al. [15] found that athletes with a concussion history performed worse in the Flanker Test. This could be due to the repeated injuries these athletes sustained, significantly hindering their cognitive performance over time. In our study, we excluded participants with a history of mTBI, and our participants were relatively younger. This could explain the non-significant differences in Flanker test performance observed in our study, as older participants who have experienced repeated concussions over time could present different symptoms than younger participants with no prior mTBI history. On the other hand, the majority of our participants were only assessed within 96 h after injury leaving time for symptoms to possibly resolve. Further studies should control for time of administration after injury more stringently by restricting the timeframe to within 24 h or less.

It is important to keep in mind that our participants were from an atypical population. The control group was composed of athletes and was not fully representative of the pediatric population. Since the mTBI experimental group included both sports related and non-sports related mTBIs, a control group with similar demographics would have contributed to a more balanced design. In addition, both our experimental and control groups were composed of only a few females. Such sex differences in mTBI injury severity have been reported in previous literature [16]. To investigate whether there are sex differences in the neurocognitive measures examined in the BrainCheck Sport Battery, future research should utilize a more evenly distributed ratio of males to females in the participants pool. Additionally, despite being a statistically significant predictor, the coordination test occasionally suffered from software malfunctioning during testing and resulted in several cases of missing data in both the experimental and control groups. As a retrospective study, it is hard to determine if all cases of malfunctioning were properly documented and fully taken into consideration.

Another possible confounding factor in our sample was the combined grouping of pre-pubescent, pubescent, and post-pubescent aged participants. While we did not observe any significant difference in age between the control and patient groups, previous work has shown that performance on computerized testing batteries improves across adolescent development at even larger magnitudes within attention and working memory cognitive domains [17], which are demonstrated to be affected by mTBI. We also sacrificed statistical power with a smaller mTBI group. While a larger experimental group would likely have given more robust results, we proceeded with statistical analysis to look for preliminary results as diagnosing pediatric mTBI is challenging. The complexity in diagnosis is multifactorial, which includes: low reliability of subjective history of symptoms relative to the adult population and the subsequent increased importance on objective findings [3], current standard of practice to avoid neuroimaging unless there are obvious signs of serious intracranial injury [1], and the large range of symptoms after concussion with a wide spectrum of cognitive impairment [9]. Thus, providing these preliminary objective data may support clinicians with a diagnostic aid in this uniquely difficult population.

Currently, there are a variety of different test batteries and screeners used in clinical practice to aid in the diagnosis of mTBI. BrainCheck Sport has potential as another option among the computerized neurocognitive tests by providing a shorter, gamified test battery that attempts to comprehensively examine and assess cognitive functioning after brain injury. This preliminary study demonstrates that BrainCheck Sport performs well in detecting and classifying mTBI patients and may be useful as a diagnostic aid.

Abbreviations

| AUC: | area under the curve |

| ED: | emergency department |

| MRHS: | Morton Ranch High School |

| mTBI: | mild traumatic brain injury |

| ROC: | receiver operating characteristic |

Declarations

Author contributions

DME and YK contributed conception and design of the study; Data acquisition was performed by BF; SY and BH performed the statistical analysis, under the supervision of RHG. SY, BK and HQP wrote the first draft of manuscript, which was revised and approved by BH and RHG. SY, BK, HQP, KS and BH revised the manuscript for submission. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The following authors declare the following competing interests: SY, BF, YK, BH, KS, RHG reports personal fees from BrainCheck, outside the submitted work; DME, BF, YK, BH, RHG reports receiving stock options from BrainCheck.

Ethical approval

This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Baylor College of Medicine IRB.

Consent to participate

Voluntary written informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from all participants.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Data may be made available by contacting the corresponding author and with a data use agreement.

Funding

BrainCheck, Inc, provided support in the form of salaries for authors SY, BF, YK, BH, KS, RHG but did not have any additional role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript, and only provided financial support in the form of some of the authors’ salaries and research materials (the software battery of tests).

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2020.