Abstract

Aim:

Human voice contains rich information. Few longitudinal studies have been conducted to investigate the potential of voice to monitor cognitive health. The objective of this study is to identify voice biomarkers that are predictive of future dementia.

Methods:

Participants were recruited from the Framingham Heart Study. The vocal responses to neuropsychological tests were recorded, which were then diarized to identify participant voice segments. Acoustic features were extracted with the OpenSMILE toolkit (v2.1). The association of each acoustic feature with incident dementia was assessed by Cox proportional hazards models.

Results:

Our study included 6, 528 voice recordings from 4, 849 participants (mean age 63 ± 15 years old, 54.6% women). The majority of participants (71.2%) had one voice recording, 23.9% had two voice recordings, and the remaining participants (4.9%) had three or more voice recordings. Although all asymptomatic at the time of examination, participants who developed dementia tended to have shorter segments than those who were dementia free (P < 0.001). Additionally, 14 acoustic features were significantly associated with dementia after adjusting for multiple testing (P < 0.05 / 48 = 1 × 10–3). The most significant acoustic feature was jitterDDP_sma_de (P = 7.9 × 10–7), which represents the differential frame-to-frame Jitter. A voice based linear classifier was also built that was capable of predicting incident dementia with area under curve of 0.812.

Conclusions:

Multiple acoustic and linguistic features are identified that are associated with incident dementia among asymptomatic participants, which could be used to build better prediction models for passive cognitive health monitoring.

Keywords

Digital voice, dementia, epidemiology, acoustic features, predictionIntroduction

Spoken language is the spontaneous and intuitive way of communication that characterizes one’s intellect and personality [1]. The effective use of language requires intact cognitive processing through the coordinated use of working memory [2], semantic memory [3] and attention [4]. Spontaneous language decline has been observed in the early stage of neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [5, 6]. Patients tend to have syntactic simplification, such as the reduction in different syntactic complexity measures [7], fewer semantic units [8] and information units [9]. Impairments in the semantic verbal fluency and lexico-semantic processing emerge early during the course of the disease, often years before symptoms of cognitive deterioration [10, 11]. A number of features derived from lexical, acoustic and syntactic aspects were associated with cognitive status, and acoustic features could separate healthy controls from amnestic mild cognitive impairment [12]. In addition, the changes in vocal variability were also associated with the disease course in a sex-specific pattern [13, 14]. Anatomical neuroimaging studies also indicate that semantic fluency and naming performance are highly correlated with neurodegeneration in the temporal and parietal lobes [15, 16]. These changes reflect both, the neurodegeneration in language specific cortical regions, as well as a loss of top-down coordination resulting from impairments in other cognitive domains such as attention and memory.

Speech alterations is one of earliest signs of cognitive decline. It is important to identify early and noninvasive biomarkers to detect pre-symptomatic biomarkers. Increasing evidence suggests that spoken language could be used as a powerful resource to derive pathologically appropriate biomarker for dementia at the earliest manifestations of the disease [16]. Studies examining the ability to distinguish individuals with cognitive impairment from typical controls based on voice and language parameters alone have reported accuracies as high as 90% [17–19]. A recent study that included 96 participants with varied cognitive status also found that natural language processing (NLP) is able to identify linguistic features of spontaneous speech to differentiate between controls and pathological states [12]. The change in the speech subsystems could affect acoustic features could be a sensitive measure of early disease progression [14]. The verbal ability has a central role among cognitive domains with early signs of decline. Linguistic analysis has identified several temporal characteristics of spontaneous speech such as number of pauses in speech and speech tempo, which showed high sensitivity to detect AD than other cognitive examinations [20].

However, prior studies are typically based on case-control studies with small numbers of selected participants, which limit their application to the general population with a diverse spectrum of cognitive health and life style factors. In addition, the effect of acoustic features on incidental dementia has been poorly characterized. Therefore, the objective of the current study is to investigate the association of acoustic features with incident dementia in the Framingham Heart Study (FHS), a community-based cohort with longitudinal collection of voice and other phenotype data.

Materials and methods

Study samples

The current study includes participants from the FHS. Three generations of participants have been enrolled since 1948. The first neuropsychological (NP) tests were administered in 1976 and a larger battery of tests across all FHS participants began in 1999. Participants have also been rigorously followed for incident neurologic outcomes (e.g., stroke, dementia, Parkinson’s disease). In addition, an extensive record of medical history, lifestyle, and genetic risk factors have been collected. Dementia was diagnosed by the dementia diagnostic review panel at FHS [21]. Given the moderate number of dementia cases, we did not separate different dementia subtypes. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Boston University Medical Center and all participants provided written consent.

NP tests and audio recordings

From 1976, a baseline NP assessment was first administered to the Framingham participants. Follow-up NP tests were performed on average 2–6 years. Details of the NP tests administered and normative values have been previously published [22–24]. These tests cover all major cognitive domains, including verbal memory, visuospatial memory, new learning, abstraction, attention and executive function, language and pre-morbid intelligence. In 2005, we began digitally recording all responses to NP test questions that required a voice response, which encompassed the spoken interactions between the tester and the participant. The recordings were stored in the wav format and were downsampled to 8 kHz. Background noise was removed using a denoiser adaptive filter. The current study included digital voice recordings from September 2005 to December 2015.

Diarization

Given that the voice of both the tester and the participant was recorded during NP tests, it is important to determine whether a participant or tester is speaking and distinguish “who spoke when [25].” This process of speaker segmentation is called diarization. A previously developed algorithm was employed to account for the language and acoustic information [26]. The algorithm was previously trained on 92 samples that were manually transcribed, and reached 0.02% confusion rate [26]. The algorithm produced timestamped speaker segments by estimating what was being spoken and who was speaking based on the spoken words. The algorithm is particularly effective for our current study because all NP tests were administered in a predictable and scripted manner. The tester always gives similar (if not identical) verbal cues for a given NP test across all examinations.

Feature extraction

OpenSMILE software (v2.1) [27] was used to extract acoustic features from voice recordings. Acoustic features derived via OpenSMILE have been previously used to assess the severity of Parkinson’s disease [28]. Recently OpenSMILE was also used to create a benchmark speech dataset to develop machine learning models for AD speech classification and NP score regression task [29]. The current study was restricted to 48 different acoustic features from OpenSMILE (Table S1). The output data consists of comma-separated files extracted from every segment with 20 milliseconds and shifting 10 milliseconds. Each column represents an acoustic feature, and each row contains the calculated acoustic feature data for a given period of 20 milliseconds. The scores were then averaged across the entire voice recording, and normalized by rank-based inverse normalization.

Statistical analyses

The association of each acoustic feature with incident dementia was assessed using Cox proportional hazards models with robust sandwich estimators (censored at the last follow-up time or death) [30]. The models were adjusted for age and sex. Participants who developed dementia before the exam were excluded. Bonferroni correction was used to adjust for multiple testing, and significant acoustic features were claimed if P < 0.05 / n, where n was the number of acoustic features to be tested.

We also created a voice score from acoustic features that were significantly associated with incident dementia. The score for sample i was defined as

where n is the number of acoustic features significantly associated with incident dementia, βj is the estimate of effect size for feature j, and Vij is the normalized score of feature j for sample i. The score represented a weighted combination of all acoustic features associated with incident dementia. A higher score represents a relatively higher dementia risk, whereas a lower score represents relatively a lower dementia risk. We then combined the acoustic score together with age and sex and investigated their association with incident dementia. The analysis was restricted to participants who were 65 years or older at the time of voice recording.

All the statistical analyses were performed using R software version 3.6.0 (https://www.r-project.org).

Results

The current study includes 4, 849 participants from the FHS (mean age 63 ± 15 years old, 54.6% women). A total of 6, 528 voice recordings had been collected at a time when participants were still free of dementia. The majority of participants (71.2%) had one voice recording, 23.9% had two voice recordings, and the remaining 236 participants (4.9%) had three or more voice recordings.

The participants were then followed for an average of 7.3 ± 3.1 years after their voice recording. One hundred and fifty-seven participants with 256 recordings were diagnosed with dementia during this period. The clinical characteristics of these participants are shown in Table 1.

Clinical characterization of study samples

| Variable | Incident dementia (n = 256) | Referents (n = 6, 272) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 83 ± 8 | 62 ± 14 | < 0.001 |

| Women, n (%) | 155 (60.5) | 3, 410 (54.4) | 0.05 |

| Average number of segments in one recording | 209 ± 85 | 142 ± 54 | < 0.001 |

| Average length of each segment, seconds | 11.4 ± 4.7 | 13.0 ± 4.0 | < 0.001 |

One participant could have multiple voice recordings.

Values are n (%), or mean ± SD. One participant could have multiple recordings;

P value was calculated by the Fisher’ exact test for categorical variables, or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables

Characterization of the voice recordings

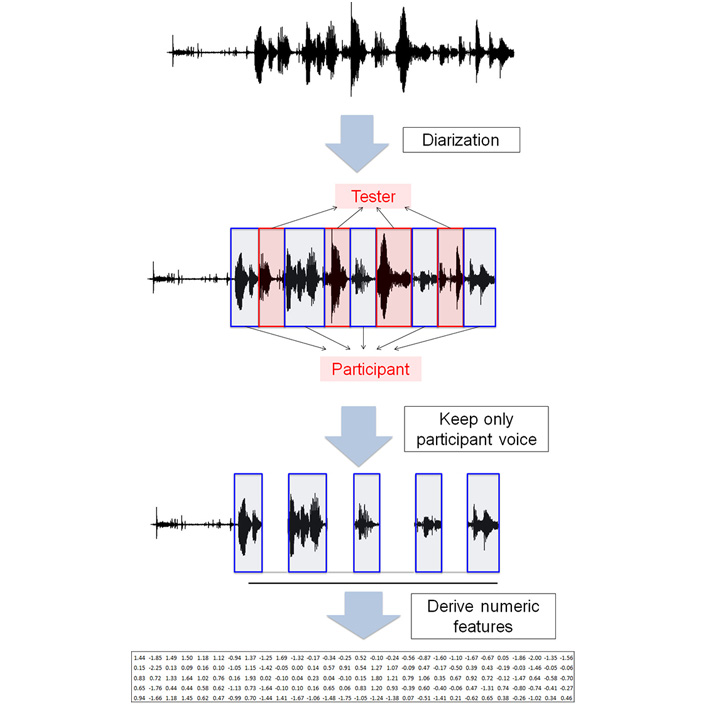

The median of the duration of the recordings was 57 min. The recording contains speech from both the tester and the participant. Figure 1 shows the workflow of data pre-processing. The raw voice recording was first cleaned to remove background noise and then diarized to identify speaker identity (tester or participant). On average, 49.1% of the recording was marked as tester speech and 50.9% was marked as participant speech.

Data preprocessing. The raw voice recording contained the voice from both the tester and the participant. Diarization was performed to remove the voice segments from the tester, and keep only the voice segments from the participants. OpenSMILE was then used to derive numeric features from voice segments

In consideration of relatively short follow up time (7.3 ± 3.1 years), as expected, participants who developed dementia tended to be older at the time when their voice recordings were collected (83 vs. 62 years old, P< 0.001). These participants who went on to develop dementia had more segments in their voice recordings than those who remained dementia free (209 ± 85 vs. 142 ± 54 segments, Student’s t-test P< 0.001). In addition, each segment tended to be shorter among those who went on to develop dementia (11.4 ± 4.7 vs. 13.0 ± 4.0 s, Student’s t-test P< 0.001).

In the sensitivity analysis, we restricted the analysis to participants who were 80 years or older at the time of the examination, so that participants would have a similar age range between those who developed dementia and those who remained dementia free during the follow-up (87 ± 5 vs. 86 ± 5 years old). Similar patterns were observed; participants who developed dementia still had more segments (219 ± 89 vs. 190 ± 66 s, P< 0.001) and short segments (11.0 ± 3.5 vs. 12.1 ± 3.6 s, P< 0.001).

Association of acoustic features with incident dementia

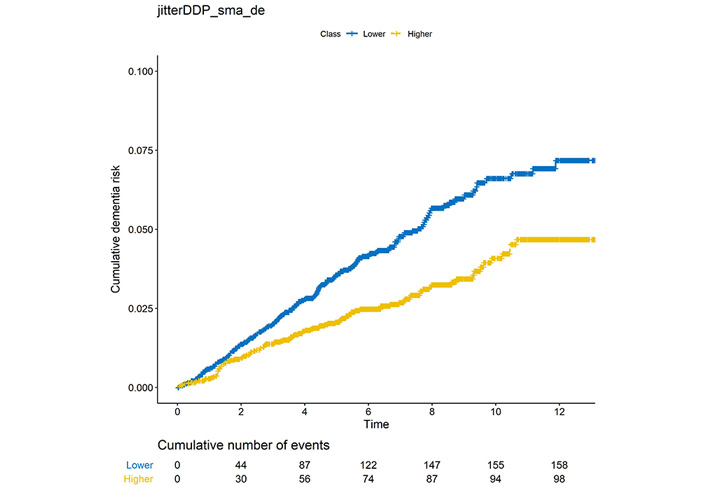

As shown in Table 2, 14 out of 48 acoustic features from OpenSMILE [27] were significantly associated with incident dementia after Bonferroni correction (P < 0.05 / 48 = 0.001). Eight of them were positively associated with dementia risk with hazard ratio (HR) higher than 1 and the remaining six acoustic features were negatively associated with dementia risk. The most significant acoustic feature was jitterDDP_sma_de (P = 7.9 × 10–7), which represents the differential frame-to-frame Jitter (the “Jitter of Jitter”); where jitter is the variation in frequency from period to period. The cumulative dementia risk of jitterDDP_sma_de is shown in Figure 2. Participants with higher jitterDDP_sma_de are more likely to develop dementia than those with lower jitterDDP_sma_de scores (P= 7.7 × 10–5). We then performed sensitivity analysis by restricting the analysis on participants who were 65 years or older at the time of voice recording. All except voicingFinalUnclipped_sma remained nominally significant (Table S2). We further performed a second sensitivity analysis by selecting age-matched referents to dementia cases. As shown in Table S3, 11 out of 14 acoustic features were still nominally significant.

Cumulative dementia risk among participants with low jitterDDP_sma_de or higher jitterDDP_sma_de. The X-axis is the follow-up time in years, and Y-axis is the proportion of cumulative dementia risk. The cumulative number of dementia events in every two years is also shown below

Association of acoustic features with incident dementia

| Marker | HR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| jitterDDP_sma_de | 0.73 | 0.65–0.83 | 7.9E–07 |

| mfcc_sma_de [4] | 0.74 | 0.65–0.83 | 1.2E–06 |

| shimmerLocal_sma_de | 0.75 | 0.66–0.84 | 3.3E–06 |

| mfcc_sma_de [3] | 0.76 | 0.67–0.86 | 1.9E–05 |

| pcm_zcr_sma_de | 1.32 | 1.15–1.50 | 3.6E–05 |

| mfcc_sma_de [1] | 0.78 | 0.69–0.88 | 6.6E–05 |

| pcm_RMSenergy_sma | 1.28 | 1.13–1.45 | 8.3E–05 |

| jitterLocal_sma | 1.29 | 1.14–1.47 | 1.1E–04 |

| audspec_lengthL1norm_sma | 1.27 | 1.12–1.43 | 1.2E–04 |

| jitterDDP_sma | 1.28 | 1.12–1.46 | 2.0E–04 |

| voicingFinalUnclipped_sma | 1.28 | 1.12–1.46 | 2.5E–04 |

| F0final_sma_de | 0.79 | 0.70–0.90 | 2.6E–04 |

| F0final_sma | 1.26 | 1.11–1.44 | 4.0E–04 |

| audspecRasta_lengthL1norm_sma | 1.25 | 1.10–1.42 | 6.2E–04 |

CI: Confidence interval

We also performed sex-stratified analysis to understand the difference in acoustic features between men and women. Table S4 shows the top acoustic features for men, whereas Table S5 shows the top acoustic features for women. Only two acoustic features (shimmerLocal_sma_de and jitterDDP_sma_de) were significantly associated with incident dementia for men after Bonferroni correction. Both acoustic features were significant in the pooled analysis. In contrast, ten acoustic features were significant for women. All of them were also significant in the pooled analysis. The most significant acoustic feature in the pooled analysis, jitterDDP_sma_de, was significant in both men (P= 8.2 × 10–4) and women (P= 1.2 × 10–4).

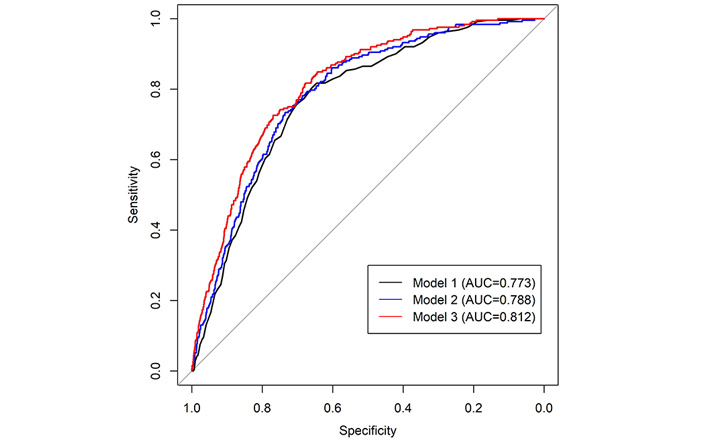

We then examined if acoustic features could be used to predict incident dementia. A weighted acoustic score was built from 14 acoustic features associated with incident dementia (see “Materials and methods”), and the distribution of the score between referents and dementia cases is shown in Figure S1. Three models were built: model 1, only included age and sex as the predictors of incident dementia; model 2, included age, sex, segment length, and number of segments as the predictors; model 3, included age, sex, segment length, number of segments, and the weighted acoustic score from 14 acoustic features associated with incident dementia. As shown in Figure 3, the inclusion of segment information and acoustic features modestly improved the prediction performance with area under curve (AUC) increasing from 0.773 (model 1) to 0.788 (model 2) and 0.812 (model 3).

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of three models to predict incident dementia. Model 1: only included age and sex as the predictors of incident dementia; Model 2: included age, sex, segment length and number of segments as the predictors; Model 3: included age, sex, segment length, number of segments, and 14 acoustic features associated with incident dementia. The inclusion of segment information and acoustic features modestly improved the prediction performance with area under curve (AUC) increasing from 0.773 (model 1) to 0.788 (model 2) and 0.812 (model 3)

Discussion

Speech represents the main channel of human communication. Speech impairment has long been observed among patients with neurodegenerative disorders. Here we used an automatic feature extraction method to derive acoustic features from more than 6, 000 audio recordings, and identified 14 acoustic features that were significantly associated with incident dementia. Participants who were later diagnosed with dementia tended to have more pauses and hesitations in their speech. We further developed a voice based linear classifier that was capable of predicting incident dementia with AUC of 0.812. Our results confirmed that differences in acoustic features might be a sign of converting to dementia [31, 32]. Our method has the potential to become an objective and efficient tool to assess future dementia risk from voice recordings before cognitive symptoms appear.

Jitter and shimmer are measures of irregular phonation, and are useful to assess variability in voiced sonorants in continuous speech. These measures have also been previously shown to have significant differences between normal and dementia subjects (specifically subjects with primary progressive aphasia) [33]. While shimmer and jitter reflect irregularities in vocal fold vibration [34], our results motivate further investigation to determine what underlying pattern and condition within our cohort relates to our findings of shimmer/jitter (i.e. their statistically significant association with dementia).

The monitoring of cognitive health is essential to the early diagnosis and intervention of dementia. A variety of screening methods have been developed to screen cognitive health, such as brain imaging [35], blood biomarkers [36, 37], and the collection of cerebrospinal fluid. However, these screening methods are expensive and/or invasive, which limit their applications to the general population without obvious symptoms. Therefore, it is crucial to develop low-cost, scalable, and effective strategies to assess cognitive health. Producing speech in the course of daily life is very easy and effortless for cognitively normal people. However, the alterations in rhythm, articulation and phonologic fluency have been observed in patients with AD [1, 38], suggesting that the voice could become a simple and noninvasive method for the early dementia diagnosis. Increasing evidence suggests that language capability can be a predictor of cognitive decline years before a clinical diagnosis of AD is made [39–42]. Cognitive impairment could alter speech production and word finding, and result in deterioration of semantic knowledge [43–45].

The complex information in human voice also presents a multitude of obstacles to analysis and interpretation of the data. Typical daily conversations include two or more people. Therefore one of the first steps is to perform diarization and locate voice segments from the speaker of interest. Our NP tests were performed in a controlled environment that included only two individuals every time (the tester and the participant), which made it relatively easy to perform diarization. Here we used a tri-gram language model for diarization, which was previously trained from 96 transcripts of NP examinations [46]. Future integration of speaker-specific language modeling together with automatic speech recognition could be an applicable method of diarizing speech in real-world scenarios.

The exploration of voice-based cognitive assessment could potentially have far reaching clinical implications. Audio recording is typically low cost with high penetration scalability that could be broadly distributed to hundreds of millions of people. In addition, voice could be captured in almost any habitual environment without the need for specialized equipment, which makes it convenient to record. We anticipate that automated speech screening will have a great potential to become an affordable and reliable method for cognitive monitoring.

The main strength of our study is the longitudinal collection of a large volume of voice data, which created a rich cognitive timeline for participants. In addition, the participants were enrolled from a community-based cohort with a wide spectrum of age, health condition, and socioeconomic status. The average duration of each voice recording is approximately one hour, which provides a great deal of voice information. All participants were asymptomatic for dementia at the time of recording, whereas some of them developed dementia in a later stage during the follow up. Therefore, this data provides a great opportunity to assess the cognitive health of the participants throughout the entire course of disease.

We also acknowledge several limitations of our study. Audio recordings were collected in a controlled environment with standardized questions, which might be different from daily conversions. The quality of audio recordings could be affected by many factors, such as the location of recorders and the environmental noises. Moreover, the voice recording was performed for the entire session of NP tests but not for each individual NP test, which would limit its specificity for some NP tests. Not all the voice segments are equally important during the conversion. Therefore, it would be useful to combine vocal features with speech recognition to further improve the prediction accuracy. In addition, only sonorant segments were studied. We did not separate different subtypes of dementia given the small number of dementia cases, nor detailed cognitive profiles for different brain functions for all participants. Some participants are still relatively young and may be in a prodromal period of dementia, who might develop dementia at a later stage. Moreover, we did not perform a comprehensive assessment of neuropsychiatric symptoms, thus their implication to speech behaviors was unclear. Finally, the vast majority of participants in our study were of European descent and English-speaking. Thus, it is unclear if our findings could be generalized to other ethnicities or language groups.

In summary, we performed automatic feature extraction and identified multiple biomarkers related to future dementia. Our result demonstrates the potential of voice biomarkers for early dementia monitoring.

Abbreviations

| AD: | Alzheimer’s disease |

| CI: | confidence interval |

| FHS: | Framingham Heart Study |

| NP: | neuropsychological |

Supplementary materials

The supplementary materials for this article are available at:

Declarations

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the dedication of the Framingham Heart Study participants without whom this research would not be possible. We also thank the FHS study staff for their many years of hard work in the examination of subjects and acquisition of data.

Author contributions

HL and RA contributed conception and design of the study. HL and CK performed the statistical analysis. HL, CK and CM drafted the manuscript. TFAA, PJ, TWA, JG and RA critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

RA has received grant funding support from Evidation Health and Biogen. She has been on the scientific advisory board of Optum Labs and serves on the scientific advisory board of Signant Health and is a scientific consultant to Biogen; none of which have any conflict of interest with the contents of this project. Other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

The Framingham Heart Study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Boston University Medical Center.

Consent to participate

All participants provided written consent to the study.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Given that voice recordings contain personal information, the dataset used in the current study is not publically available. However, the scripts and tools are available upon request.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute contract (N01-HC-25195) and by grants from the National Institute on Aging AG-008122, AG-16495, AG-062109, AG049810, AG054156, and from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, NS017950. It was also supported by Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency contract (FA8750-16-C-0299); Pfizer, Inc; the Boston University Digital Health Initiative; Boston University Alzheimer Disease Center Pilot Grant; and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Boston University Clinical & Translational Science Institute Grant Number 1UL1TR001430. This work was also supported by the Alzheimer’s Association Grant (AARG-NTF-20-643020). The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institutes of Health or the US Department of Health and Human Services. The funding agencies had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2020.