Abstract

Gout is the most common inflammatory arthritis and a global health problem. In addition to joint involvement, urate crystals induce chronic inflammation, leading to increased cardiovascular risk in gout. Thus, cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in gout and numerous studies have revealed an increase in cardiovascular-related mortality in these patients. However, despite the efficacy of urate-lowering therapies, such as allopurinol and febuxostat, suboptimal management of gout and poor adherence continue to make it difficult to achieve better outcomes. Treat-to-target strategy may help change this, as in other diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis. Nevertheless, even with a well-defined clinical target (absence of flares and tophi disappearance), the numerical target [serum uric acid (SUA) < 5 mg/dL or < 6 mg/dL] still varies depending on current guidelines and consensus documents. Recently, several trials [Long-Term Cardiovascular Safety of Febuxostat Compared with Allopurinol in Patients with Gout (FAST), REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS)] have shown better cardiovascular outcomes in those patients who achieve SUA levels < 5 mg/dL. Likewise, some observational studies, mostly based on imaging tests such as ultrasound and dual-energy computed tomography, have found better results in the magnitude and speed of reduction of urate joint deposition when SUA < 5 mg/dL is achieved. Based on an analysis of the available evidence, SUA < 5 mg/dL is postulated as a more ambitious target within the treat-to-target approach for the management of gout to achieve better joint and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with cardiovascular risk or severe disease.

Keywords

Gout, uric acid, urate, crystals, treat-to-target, cardiovascular, arthritisGout is widespread in the general population. It is the most common cause of inflammatory arthritis and constitutes a global public health problem [1]. The presence of monosodium urate (MSU) crystals induces an innate immune response, leading to chronic inflammation [2]. This is responsible for the increased cardiovascular risk (CVR) in gout, which cannot be explained by traditional risk factors alone [3].

Treatment of gout aims to dissolve urate deposits. This is the only approach that makes tophi (ordered structures of MSU crystals, sometimes detectable under the skin by physical examination) and recurrent arthritis attacks disappear definitively, eliminates systemic inflammation, and reduces extra-articular repercussions of the disease, such as kidney and cardiovascular disease [4].

Xanthine oxidase inhibitors (XOI), such as allopurinol and febuxostat, are widely used in the management of gout. They reverse the disease process, lowering serum uric acid (SUA) by blocking the enzyme that catalyzes the transition from xanthine to uric acid, thus favoring the dissolution of urate deposits. According to the main international guidelines, allopurinol is recommended as the first-line urate-lowering treatment (ULT), while febuxostat and uricosuric drugs (alone or in combination with XOI) should be considered if the SUA target is not achieved with allopurinol [5, 6]. However, despite the efficacy of all these ULTs, suboptimal medical management of gout and poor adherence on the part of patients make it difficult to achieve better outcomes in this well-known and prevalent disease, which has serious clinical and socioeconomic consequences [7].

To help change this, the treat-to-target strategy was introduced more than a decade ago. Treat-to-target aims to manage gout by providing better therapeutic outcomes, as in other diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and diabetes mellitus [8]. This approach includes a numerical target and a clinical target; the first helps to achieve the second. The clinical target is the disappearance of arthritis attacks and tophi. The numerical target varies depending on current guidelines and consensus documents, as follows: SUA < 6 mg/dL according to the American College of Rheumatology; < 6 mg/dL and < 5 mg/dL (in severe gout) according to the European League Against Rheumatism [5, 6]. These recommendations are based on the idea of favoring the dissolution of urate deposits by lowering SUA beyond the saturation point (6.8 mg/dL; SUA precipitates in MSU crystals at concentrations higher than 7 mg/dL) [9] and is supported by several studies that have reported fewer gout attacks in patients who maintain SUA ≤ 6 mg/dL [10–14].

However, there are no science-based proposals to define a numerical target for gout patients with cardiovascular events (CVE) or focused on CVR. Data from the Cardiovascular Safety of Febuxostat and Allopurinol in Patients with Gout and Cardiovascular Morbidities (CARES) trial recommend not using febuxostat in patients with gout and coexisting cardiovascular disease, the most powerful urate-lowering XOI [15]. Furthermore, in the design of the Febuxostat/Allopurinol Comparative Extension Long-Term (EXCEL) trial, patients with SUA < 3 mg/dL were reassigned to ULT from their initial treatment, this being the most frequent cause of withdrawal (14%) in the febuxostat arm [16]. Even so, CARES only included patients with a previous CVE and did not include patients with CVR only. The recently published results of the Long-Term Cardiovascular Safety of Febuxostat Compared with Allopurinol in Patients with Gout (FAST) trial, a post-marketing clinical study with more than 6,000 patients and a median follow-up close to 5 years sponsored by the European Medicines Agency to resolve the concerns raised about the cardiovascular safety of febuxostat in gout, includes both CVE and CVR [17]. In a pre-specified subanalysis included in the original design, fewer CVEs were recorded in patients with SUA < 5 mg/dL during treatment with febuxostat than in those with SUA ≥ 5 mg/dL.

Therefore, according to the results of FAST, the following conclusions can be drawn: a) febuxostat is not associated with higher global or cardiovascular morbidity and mortality; b) SUA levels < 5 mg/dL reduce CVE rates and might be a target for patients with previous CVE or high CVR. However, we must also accept the following limitations of this trial: a) it does not include patients with class III/IV heart failure; b) it is unknown whether the beneficial cardiovascular effect obtained disappears when low levels of SUA are not permanently maintained, or whether that benefit is partially due to the use of antiplatelet agents (majority use in FAST in patients with previous CVE, minority use in CARES despite previous CVE); c) there is no analysis by clinical subgroup (CVE versus CVR) or drug-dose subgroup (allopurinol versus febuxostat). Finally, several studies have found a non-linear association between SUA levels and cardiovascular mortality in adults, with the lowest mortality for values of about 4–5 mg/dL [18–21]. A recent case-cohort analysis of Black and White’s participants aged ≥ 45 years with no history of coronary heart disease enrolled in the REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study reported significant differences in the risk for sudden cardiac death between those with SUA ≥ 6.8 mg/dL and those with < 5 mg/dL [hazard ratio 2.14; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.40–3.26] [22].

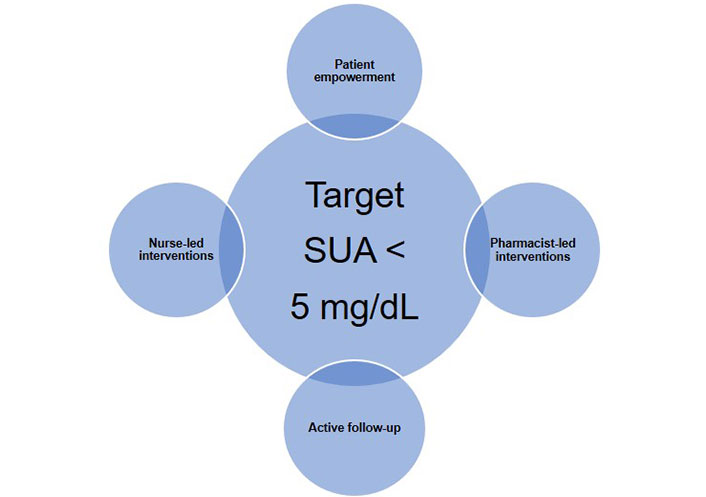

Observational studies also have shown that the lower the SUA, the better the joint clinical outcomes, owing to the faster dissolution of the MSU deposits [23, 24]. Likewise, studies using dual-energy computed tomography or ultrasonography to assess the urate crystal burden in joints found a more significant decrease in MSU deposits in gout patients who achieve SUA < 5 mg/dL with appropriate treatment [25, 26]. Curiously, in the Sons of Gout Study, Abhishek et al. [27] did not find urate deposition in asymptomatic patients with SUA ≤ 5 mg/dL and a family history of gout, whereas ultrasound revealed MSU deposits in 24.2% of those with SUA between 5 mg/dL and 6 mg/dL. Since several studies have found a significant relationship between the total burden of urate deposits and CVR, improving the efficiency of urate deposit dissolution with an ambitious urate target should be mandatory when attempting to improve prognosis [28, 29]. At this point we must emphasize the need to also include other non-pharmacological strategies in the holistic management of CVR in gout patients, promoting a healthy lifestyle and controlling comorbidities such as chronic kidney disease or metabolic syndrome, both closely related to hyperuricemia and gout. We also strongly support active follow-up, patient empowerment, and nurse/pharmacist-led interventions to improve adherence to ULT and follow-up, as well as reduce/avoid taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), thus helping to achieve analytical and clinical goals (Figure 1) [30].

Proposal for a strategic approach to achieve the target of SUA < 5 mg/dL in patients with gout

In conclusion, we suggest SUA < 5 mg/dL as a more ambitious target within the treat-to-target approach for the management of gout in order to achieve better joint and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with CVR or severe disease. More studies are needed to replicate the FAST results when lower SUA targets are achieved.

Abbreviations

| CARES: | Cardiovascular Safety of Febuxostat and Allopurinol in Patients with Gout and Cardiovascular Morbidities |

| CVE: | cardiovascular events |

| CVR: | cardiovascular risk |

| FAST: | Long-Term Cardiovascular Safety of Febuxostat Compared with Allopurinol in Patients with Gout |

| MSU: | monosodium urate |

| SUA: | serum uric acid |

| ULT: | urate-lowering treatment |

| XOI: | xanthine oxidase inhibitors |

Declarations

Author contributions

ECA: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. FPR: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Supervision. Both authors read and approved the submitted version.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Spanish Foundation of Rheumatology (FERBT2022). The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2023.