Affiliation:

Department of Neurosurgery, Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, 08097 Barcelona, Spain

Email: mariaciscar@bellvitgehospital.cat

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0005-8039-6272

Affiliation:

Department of Neurosurgery, Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, 08097 Barcelona, Spain

Affiliation:

Department of Neurosurgery, Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, 08097 Barcelona, Spain

Affiliation:

Department of Neurosurgery, Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, 08097 Barcelona, Spain

Affiliation:

Department of Neurosurgery, Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, 08097 Barcelona, Spain

Affiliation:

Department of Neurosurgery, Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, 08097 Barcelona, Spain

Explor Neurosci. 2024;3:539–550 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/en.2024.00065

Received: August 09, 2024 Accepted: September 23, 2024 Published: October 29, 2024

Academic Editor: Katrin Sak, NGO Praeventio, Estonia

The article belongs to the special issue Current Approaches to Malignant Tumors of the Nervous System

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is characterized by its infiltrative growth pattern and high recurrence rate despite treatment. While local progression within the central nervous system (CNS) is the rule, manifestations outside the CNS, particularly skin and subcutaneous metastases, are very infrequent and seldom reported in the literature. The authors reviewed the current understanding of this rare condition, with the main purpose of giving visibility to its clinical presentation and prognostic implications, thus improving clinical management and encouraging research in this area. A PubMed, Cochrane Library, and EMBASE search from database inception through March 2024 was conducted. In this way, we compiled a total of thirty-five cases in our review. As far as we know, our work gathers the largest number of patients with this condition. Remarkably, we observed that the typical presentation of soft-tissue high-grade glioma metastases is the finding of subcutaneous erythematous nodules in patients previously operated on for a primary CNS tumor, within the craniotomy site and nearby, mostly in the first year after the initial surgery. It was also noted that there is a trend of developing a concomitant CNS recurrence and/or other metastases in different locations, either simultaneously or subsequently. From here, we propose some possible mechanisms that explain the extracranial spread of GBM. We concluded that a poor outcome is expected from the diagnosis of skin and subcutaneous metastases: the mean overall survival was 4.38 months. Yet, assessing individual characteristics is always mandatory; a palliative approach seems to be the best option for the majority of cases.

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is the most common malignant primary central nervous system (CNS) tumor in adults. The GBM incidence generally rises with age, with a median age at diagnosis of 64 years. In addition, an aggressive clinical course and a high rate of local recurrence define the disease, with a poor overall prognosis; being the survival rate at 2 years (95% CI) is 14.8% (14.3–15.2), and at 10 years (95% CI), 2.6 % (2.3–2.9) [1]. On the other hand, GBM typically spreads locally within the CNS, infiltrating nearby brain tissue, and making distant metastasis uncommon. However, sporadic cases of extracranial metastasis have been reported, including instances of dissemination to organs such as the lungs, liver, and bones [2–6]. Nevertheless, among the variety of patterns, the phenomenon of subcutaneous dissemination stands as a highly unusual form of recurrence. We conducted a review of the literature to provide context to this entity, its features, the different management strategies, and its natural history.

A PubMed, Cochrane Library, and EMBASE search from database inception through March 2024 was conducted using combinations of the search terms “glioblastoma” AND “subcutaneous/skin/scalp” AND “metastasis” OR “dissemination” OR “progression.” Full-text articles published in the English and Spanish literature were included if they reported on patients with this finding, despite the systemic disease progression or other concomitant findings. Reports of GBM metastasis without skin and/or subcutaneous tissue involvement were excluded. In this way, we reviewed twenty-eight articles (Table 1) and a total of thirty-four cases of soft-tissue high-grade glioma dissemination, increasing to thirty-five after including ours. As far as we know, our work gathers the largest number of patients with this condition. The previous broadest review was made by Lewis et al. (2017) [7] with seventeen cases.

Literature review of skin and subcutaneous metastasis in high-grade glial tumors

| References | Age at diagnosis (years) | Sex | Primary location | Surgery (grade of resection) | Adjuvant treatment | Time from first surgery to scalp metastasis (months) | Relevant features of metastasis | CNS progression (local intracranial recurrence) simultaneously or deferred | Other manifestations after scalp metastasis | Management of scalp metastasis | Survival from scalp metastasis diagnosis (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matsuyama et al., 1989 [2] | 68 | M | Right sylvian fissure and small masses in cisterns | GT | RT + CT | Unknown | Scalp nodule at the craniotomy site and/or nearby | Unknown | Autopsy revealed metastases to the liver, spleen, and spinal cord | Palliative approach | Unknown |

| Carvalho et al., 1991 [16] | 26 | F | Posterior right temporal | ST | RT + BT | Unknown | Scalp nodule at the craniotomy site and/or nearby | Yes, simultaneously | A cervical lymph node, and afterward other extracranial masses (not specified) | RT + CT + excision of the affected soft-tissue | Unknown |

| Wallace et al., 1996 [17] | 41 | M | Right frontal | GT | RT + CT | 3 | Scalp nodule at the craniotomy site and/or nearby | Unknown | Painful bilateral cervical adenopathies | RT + CT | 5 |

| 39 | M | Right frontal-temporal | GT | RT | 5 | Scalp nodule at the craniotomy site and/or nearby | Yes, simultaneously local recurrence with extension through the overlying skull and along the anterior fossa into the right orbit | Neck and facial swelling with a preauricular lymphadenopaty | CNS surgery | 7 | |

| Houston et al., 2000 [3] | 19 | M | Left parietal | ST | BT | 10 | Scalp and skull nodules in the suboccipital region | Yes, 4 months later | 4 months later, a supraclavicular node and a mediastinum mass | RT + CT | 7 |

| 32 | M | Left temporal | ST | BT + CT | 5 | Scalp nodule at one of the healed left frontal catheter sites | Yes, 2 months later | 8 months later, lung and liver metastasis | Excision of the affected soft-tissue + CNS surgery after detecting CNS progression | 8 | |

| Hata et al., 2001 [4] | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | RT + CT | Unknown | Scalp nodule at the craniotomy site and/or nearby | Yes, simultaneously local invasion of the primary tumor to the dura and skull | Multiple tumors in the lung, lymph nodes, and the heart, simultaneously | Unknown | Unknown |

| Figueroa et al., 2002 [18] | 34 | M | Left temporal | P | RT | 8 | Subcutaneous nodule 3.5 cm anterior to the frontal scalp line and 2 cm posterior | Yes, simultaneously | No | Excision of the affected soft-tissue | 5 |

| Santos et al., 2003 [19] | 42 | M | Left fronto-parietal | GT | RT + CT; after, two CNS recurrences required two different surgeries and cycles of RT + CT | 36 | Scalp nodule at the craniotomy site and/or nearby | No | No | Excision of the affected soft-tissue | Unknown |

| Allan, 2004 [20] | 60 | M | Frontal-temporal (side not specified) | P | RT | 12 | Scalp nodule at the craniotomy site and/or nearby | Yes, simultaneously | No | Palliative approach | 2 |

| Moon et al., 2004 [21] | 35 | F | Left temporo-occipital | ST | RT; after, three CNS recurrences required three different surgeries | 48 | Scalp nodule at the craniotomy site and/or nearby | Yes, simultaneously. Extense leptomeningeal spread to the left temporo-occipital region | Multiple lymph adenopathies in the deep cervical region without continuity with the scalp mass, simultaneously | CT | 5 |

| Bouillot-Eimer et al., 2005 [22] | 60 | F | Left parietal | B | RT + CT | 11 | Scalp nodule at the craniotomy site and/or nearby | Yes, simultaneously. Intracraneal tumor seeding along the stereotactic biopsy trajectory | No | Excision of the affected soft-tissue | 1 |

| Jain et al., 2005 [11] | 49 | M | Right temporo-parietal | P | RT | 10 | Scalp nodule at the craniotomy site and/or nearby | Yes, simultaneously | No | Excision of the affected soft-tissue | 2 |

| Schultz et al., 2005 [10] | 74 | F | Left temporal | P | Unknown | 12 | Scalp nodule at the craniotomy site and/or nearby | Yes, simultaneously | No | Excision of the affected soft-tissue | 1 |

| Saad et al., 2007 [5] | 13 | M | Left frontal | ST | RT + CT + antiangiogenic therapy | 7 | Scalp nodule at the craniotomy site and/or nearby | Yes, simultaneously intracranial and leptomeningeal spread | Multiple liver and lung metastatic nodules, simultaneously | Palliative approach | 3 |

| Mentrikoski et al., 2008 [23] | 58 | F | Left frontal | GT | RT + CT; after two CNS recurrences required two different surgeries and antiangiogenic therapy + RT | 16 | Scalp nodule at the craniotomy site and/or nearby | No | No | Unknown | Unknown |

| 47 | M | Not specified | GT | CT | 2 | Scalp nodule at the craniotomy site and/or nearby | No | No | Unknown | Unknown | |

| Senetta et al., 2009 [12] | 48 | F | Right fronto-parietal | GT | RT + CT | 14 | Scalp nodule at the craniotomy site and/or nearby | Yes, 4 months later | No | Excision of the affected soft-tissue + RT + CT | 12 |

| 53 | F | Left frontal | P | RT + CT | 9 | Scalp nodule at the craniotomy site and/or nearby | Yes, 4 months later | 3 months later, new scalp satellite lesions | RT | 16 | |

| Miliaras et al., 2009 [24] | 63 | M | Left fronto-parietal | GT | Unknown | 7 | Scapular subcutaneous mass | Yes, 1 month later | No | Unknown | 3 |

| Jusué Torres et al., 2011 [25] | 63 | F | Right frontal | GT | RT + CT | 6 | Scalp nodule at the craniotomy site and/or nearby | Yes, simultaneously | No | Excision of the affected soft-tissue + CNS surgery + carmustine implants + CT + antiangiogenic therapy | Unknown |

| Guo et al., 2012 [26] | 19 | F | Pons of brain stem | Unknown | RT + CT | 8 | Scalp nodule at the craniotomy site and/or nearby | Yes, simultaneously | No | Excision of the affected soft-tissue + CT + RT | Unknown |

| Amitendu et al., 2012 [27] | 27 | M | Right temporal | GT | After PXA diagnosis, an RT regimen was carried out | 48 | Scalp nodule at the craniotomy site and/or nearby | Yes, 3 months later. After excision, the histology showed anaplastic oligodendroglioma (WHO III). | 6 months later, lumbosacral spinal metastasis | Excision of the affected soft-tissue + surgery of lumbosacral spinal metastasis | Unknown |

| Ginat et al., 2013 [28] | 62 | M | Left frontal extending to ependimal surface | ST | RT + CT | 10 | Scalp nodule at the craniotomy site and/or nearby | Yes, afterwards (unespecified) | No | Excision of the affected soft-tissue + CT + RT | 3.5 |

| Bathla et al., 2015 [14] | 51 | M | Left parafalcine with | GT | RT + CT | 1.5 | Scalp nodule at the craniotomy site and/or nearby | Unknown | No | Palliative approach | 2 |

| Anghileri et al., 2015 [6] | 30 | M | Left central sulcus | Unknown | RT + CT; two CNS recurrences required two different surgeries afterward | 80 | Frontal subcutaneous lump | No | 2 months later, cervical lymph nodes and multiple lung metastasis | Excision of the affected soft-tissue | 2 |

| 43 | M | Left anterior frontal | GT | RT + CT; two CNS recurrences required two different surgeries | 20 | Frontal subcutaneous lump | Yes, simultaneously | No | Excision of the affected soft-tissue | 1 | |

| Forsyth et al., 2015 [29] | 59 | F | Left fronto-temporal | Unknown | RT + CT | 6 | Frontal subcutaneous lump | Yes, simultaneously | No | CNS surgery | Unknown |

| Lewis et al., 2017 [7] | 47 | F | Left medial cerebellar hemisphere extending to the vermis | GT | RT + CT | 5 | Scalp nodule at the craniotomy site and/or nearby | Yes, simultaneously ecurrence at leptomeninges, fourth ventricle, and drop metastases in the cervical vertebrae | No | RT + CT + Excision of the affected soft-tissue | Unknown |

| Pérez-Bovet and Rimbau-Muñoz, 2018 [30] | 63 | F | Right fronto-parietal | ST | RT + CT | 10 | Scalp nodule at the craniotomy site and/or nearby and palpable nodules in the masticator muscles of the right infratemporal fossa | Yes, 4 months later | No | Excision of the affected soft-tissue + CNS surgery + CT | 1.5 |

| Magdaleno-Tapial et al., 2019 [13] | 75 | F | Right parietal | GT | Clinical trial with nivolumab/placebo | 7 | Scalp nodule at the craniotomy site and/or nearby | No | No | Palliative approach | Unknown |

| Moratinos-Ferrero et al., 2019 [31] | 51 | M | Right temporo-parietal | GT | Unknown | 8 | Scalp nodule at the craniotomy site and/or nearby | Yes, simultaneously | No | Unknown | Unknown |

| 53 | M | Left temporo-parietal | GT | Unknown | 18 | Scalp nodule at the craniotomy site and/or nearby | Yes, simultaneously | No | Unknown | Unknown | |

| Nakib et al., 2021 [32] | 53 | M | Posterior limb og the right internal capsule and right thalamus | ST | RT + CT + antiangiogenic therapy | 11 | Anterior-auricular side of his face is near-distant from the surgery scar | Yes, simultaneously | No | Palliative approach | 4 |

| Ciscar-Fabuel et al., 2024 [9] | 48 | M | Left parietal multifocal | GT | RT+CT | 6 | Scalp nodule at the craniotomy site and/or nearby | Yes, 1 month later | No | Excision of the affected soft-tissue | 1 |

M: male; F: female; GT: gross total resection; RT: radiotherapy; CT: chemotherapy; ST: subtotal resection; BT: brachytherapy; CNS: central nervous system; P: partial resection; B: biopsy; PXA: pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma; WHO: World Health Organization

In the whole of the review, the histopathological exam showed a glial lineage and a high grade following the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of CNS tumors. We use the term glioblastoma, high-grade glioma, or high-grade glial tumor indistinctly. However, according to the 2021 version of this classification, the previously called GBM is divided into two different diagnoses based on IDH mutation status: glioblastoma, IDH-wildtype, CNS WHO grade 4; and astrocytoma, IDH-mutant, CNS WHO grade 4 [8]. Even though this feature is important to the current understanding of the disease, we couldn’t specify the IDH mutational state of the cases compiled here because nearly all of the publications were made before this latter classification, and the information on IDH mutational state is not always given.

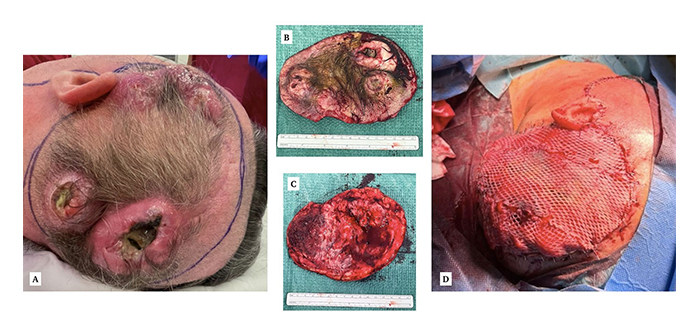

The recognition of extracranial metastasis of GBM holds significant clinical implications, since it poses a diagnostic challenge due to its resemblance to dermatological conditions (Figure 1) such as angiosarcoma, melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, or basal cell carcinoma [9, 10]. Nonetheless, the majority of soft-tissue metastases were found at the craniotomy site and/or nearby, in the form of subcutaneous erythematous nodules. In all cases, the soft-tissue lesions appeared after diagnosing and operating on a primary GBM, and an excisional biopsy, punch biopsy, or fine-needle aspiration confirmed the pathological anatomy.

The case treated in our center. A: Macroscopic appearance of the scalp nodules, two of which have visible necrosis and suppuration. B: Surgical piece, external. C: Surgical piece, internal. D: Final result after covering the defect with a thoracodorsal artery perforator (TDAP) flap and split-thickness skin grafts. Reprinted from Ciscar-Fabuel et al. [9]. © The Authors 2024. CC BY

With regard to high-grade glioma extracranial spread mechanisms, several have been postulated. One prominent theory suggests that tumor cells acquire invasive properties, allowing them to breach the blood-brain barrier and enter the bloodstream or lymphatic system, facilitating dissemination to distant organs. Tumor cells release pro-angiogenic factors, promoting the development of a dense vascular network that facilitates tumor growth and metastatic spread [1]. Moreover, interactions between GBM cells and the extracellular matrix (ECM) contribute to metastasis by promoting cell adhesion, migration, and invasion [11]. Angiogenesis seems to be relevant too. Immune evasion mechanisms also contribute to metastatic dissemination [1].

And when we focus on skin and subcutaneous GBM spread, tumor cells may undergo epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a process associated with increased migratory and invasive capabilities, furthering metastasis. Senetta et al. [12] described two cases of GBM skin metastases in the absence of intracranial progression, associated with a shift toward a mesenchymal immunophenotype (reduction of GFAP and EGFR staining paralleled by increased vimentin and YKL-40 expression), suggesting the selection of a therapy-resistant subpopulation of neoplastic cells in the metastatic sites, induced either by treatment [radiotherapy (RT)-induced morphological changes] or determined by the tumor environment.

Also, among the thirty-five cases, the mean age was 47.21 years, the youngest being 13 years [5] and the oldest 75 [13]. About sex distribution, there were 21 males and 13 females (1 of the cases was not defined). The average time from the first surgery to skin and/or subcutaneous metastasis was 14.36 months. The standard deviation is 16.49 months, suggesting a wide range of values. The minimum time to metastasis recorded was 1.5 months [14], and the maximum was 80 months [6]. A larger number of patients experienced metastasis earlier (within the first few months from primary tumor diagnosis): the median time from the first surgery to skin and/or subcutaneous metastasis was 9.5 months, with 25% of the cases having metastasis by 6 months and 75% by 12.5 months. Comparatively, CNS recurrences of GBM are seen mostly between 6 and 9 months [15]. We couldn’t find a statistically significant correlation among the grade of resection [gross total (GT), subtotal (ST), partial (P), biopsy (B)] and time to metastasis. On the other hand, 55.8% of patients (19 out of 34) had CNS progression by the time metastasis was found. In addition, another 9 patients had a CNS progression afterward. This means that 82.35% of patients (28 out of 34) had CNS progression at the same time or after diagnosing the skin and/or subcutaneous dissemination. Conspicuously, 26.47% of them had metastasis in different locations (9 out of 34), such as lymph nodes, lungs, liver, or spleen, simultaneously or afterward [2–6]. Though not in all cases was an extension study conducted; in the majority, just a head computerized tomography scan was performed.

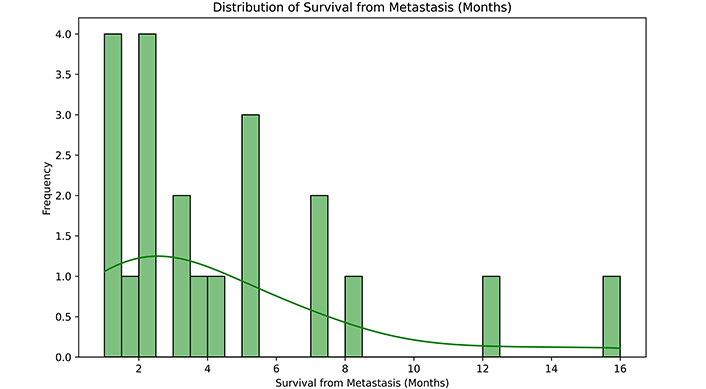

Finally, regarding the management, some authors, including us, advocated for surgery to achieve the highest cytoreduction and to avoid local, and/or systemic complications; nonetheless, it must be taken into account that other complications from surgery can occur (local pain, bleeding, infection, or ulceration are some examples). Other authors combined RT and chemotherapy (CT) schemes, while others directly chose a palliative approach. In any case, this doesn’t seem to have a significant impact on overall survival. We observed a mean survival time from scalp metastasis of 4.38 months, with a standard deviation of 3.89. The shortest survival time from metastasis recorded was 1 month our case [9] the longest was 16 months [10]. The median survival time from metastasis was 3 months, and most patients passed away within 5 months or less from scalp metastatic disease (Figure 2). Meanwhile, the median overall survival after high-grade glioma CNS recurrence ranges from 3 to 9 months [15].

Survival from scalp metastasis (months). This histogram with a kernel density estimate illustrates the spread and central tendency of the survival times from metastasis. In quartiles: 25% of patients had a survival time of 2 months or less, 50% had a survival time of 3 months, and 75% of 5 months

This review highlights a rare form of progression of the more frequent malignant primary CNS tumor. GBM still presents a profound oncological challenge. The majority of cases reviewed debuted with scalp erythematous nodules located within the surgical scar or close to it. In any event, if extracranial recurrence of high-grade glioma is suspected, histopathological confirmation is always necessary for a definitive diagnosis.

The median time from the first surgery to skin and/or subcutaneous metastasis was 9.5 months, with 25% of the cases having metastasis by 6 months and 75% by 12.5 months. Thus, we can affirm that most of the skin and subcutaneous metastasis of GBM occurs within the first year following primary surgery. It doesn’t differ greatly from CNS recurrences of GBM that largely happen between 6 and 9 months after the first surgery [15]. We must also note that 82.35% of patients had CNS progression at the same time or after the diagnosis of skin and/or subcutaneous dissemination, and 26.47% had metastasis in different locations (lymph nodes, lungs, liver, or spleen are some examples) [2–6]. In this way, we consider it appropriate to perform a new computerized tomography brain scan and an extension study before decision-making. The extension study should include at least a blood test with hepatic and renal profiles, and a thoracoabdominal computerized tomography scan in order to rule out systemic dissemination. Besides, we perceive this condition as a poor prognostic factor since the mean survival time from the diagnosis of scalp metastasis was 4.38 months, and most of the patients, more precisely 75%, passed away before 5 months. For its part, an isolated CNS recurrence entails an overall survival that ranges from 3 to 9 months. This doesn’t seem to make a difference between both forms of recurrence but emphasizes the importance of palliative care, where excisional surgery of the scalp lesions seems suitable if the metastatic form of the disease endangers the patient’s quality of life, yet does not have a statistically significant impact on the prognosis as we mentioned before, and it can be with different complications such as bleeding, ulceration, or infection.

In this respect, the main limitation of our review was its retrospective and observational nature. We couldn’t establish a consensus regarding management, where the only mandatory aspect seems to be the unique patient attributes (age, performance status, presence of concomitant CNS recurrence…) in the risk-benefit balance of each decision. Moreover, for the reasons given above, we couldn’t compile information about immunohistochemistry, which at present seems very important to understanding the mechanisms driving glioblastoma recurrence and may be a therapeutic key in the foreseeable future. It is our hope to enhance awareness of this condition among the neurosurgical and medical community, as well as to stimulate further research and collaborative efforts to gain a better understanding of the pathophysiology, and in this way, develop tailored therapeutic approaches for improved patient outcomes.

CNS: central nervous system

CT: chemotherapy

GBM: gioblastoma multiforme

IDH: isocitrate dehydrogenase

RT: radiotherapy

WHO: World Health Organization

MCF: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology. ADVB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. GBP: Investigation, Methodology, Visualization. MRQ: Project administration, Visualization. GPA and AGC: Supervision, Validation, Visualization.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

The informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from all participants.

The informed consent to publication was obtained from relevant participants.

The primary data for this review were sourced online from databases listed in the methods. Referenced articles are accessible on PubMed, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library. Additional supporting data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2024.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2024. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 2722

Download: 25

Times Cited: 0

Zohreh Khosravi Dehaghi

Maria Ciscar-Fabuel ... Andreu Gabarros-Canals

Julius Mulumba ... Yong Yang

Adam H. Lapidus, Malaka Ameratunga